Home > Articles > The Archives > Wes Golding

Wes Golding

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April 1989, Volume 23, Number 10

Wesley Golding is already well known to most bluegrass fans as a key member of the 1970s supergroup Boone Creek. Highly regarded as a powerful, innovative singer and guitarist in his own right, Golding is also well remembered for his productive stints with the Shenandoah Cutups and a spin-off group, the Country Grass. But Wesley is definitely not a musician to rest on his own considerable laurels for long; not surprisingly, he has emerged in the vanguard of today’s best young bluegrass songwriters as well as performing with his own fine band, Sure Fire.

Born to Wayne C. and Ossie King Golding in Lambsburg, Virginia, in 1955, Wesley Creed Golding grew up with music around the house. “My grandfather, Jack Golding, played old-time fiddle,” Wes recalls “and my grandmother, Gracie, played clawhammer-style banjo. I especially remember listening to her playing.” In addition, other relatives were musically inclined, including Golding’s father and one of his mother’s sisters. “My father used to pick guitar around at different houses in the neighborhood; as a kid I used to go with him and stay out all night,” Wes remarks with a chuckle. “Also, my aunt, Betty King used to sing and play guitar with my dad.” From this aunt, Golding learned to play his first tune on guitar, “Tom Dooley.”

Wayne Golding, who worked in the Proctor-Silex appliance factory in nearby Mt. Airy, North Carolina, finally purchased his son a guitar—at the grandfather’s urging. “That first one was a Truetone,” remembers Wes.

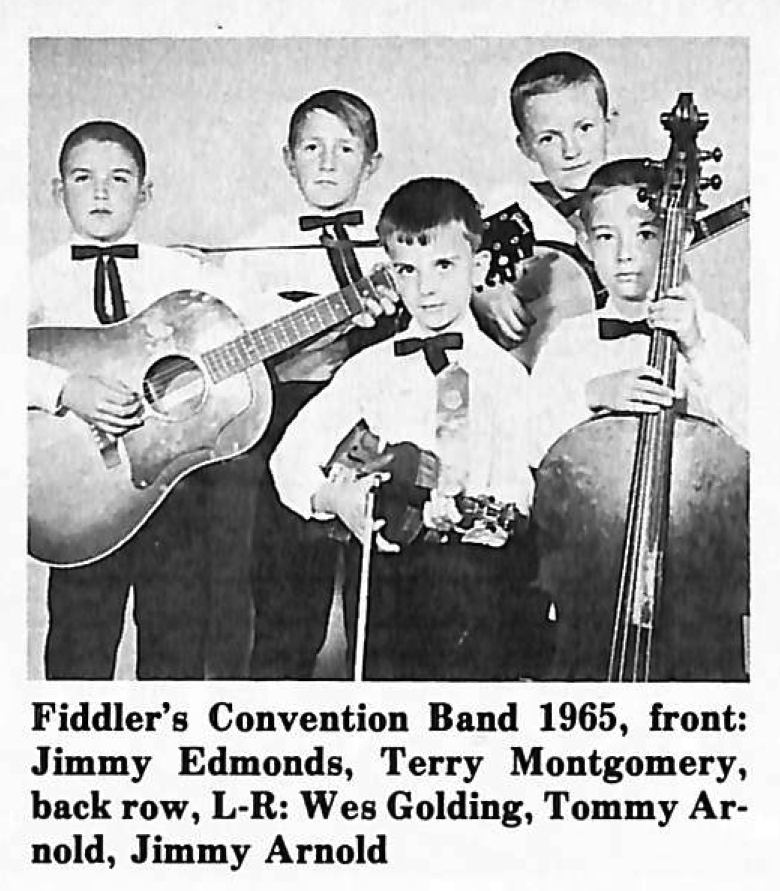

The inevitable acquisition of his own instrument in the early 1960s doubtless spurred the fledgling musician to form his first group: a band composed of talented youngsters appropriately dubbed “The Playmates.” Golding recalls, “There were three or four kids around who played music. Our little group consisted of six-year-old Jimmy Edmonds, from Galax, who had learned to play old-time fiddle from his granddad; Jimmy Arnold from Fries, who was eleven and played banjo and I was eight years old and played guitar. All of us lived within about 25 miles of each other and we went to a lot of fiddlers’ conventions back then. We did win some prizes at the competitions, some of them probably because we were so young.” The Playmates’ repertoire was mostly old-time fiddle tunes like “Sally Ann” and “Arkansas Traveler.”

“Probably my biggest influence in the early days would have been my dad, especially the singing,” Wes says. “He was an accomplished singer himself and really taught me a lot.” Wayne Golding gave his son a nice Christmas gift one year—a red sunburst Gibson J-45 guitar. The stage was set for Wesley to embark on his bluegrass career.

Both Wesley and Jimmy Arnold were only children—neither had siblings—although Golding was to have a sister, Michelle, much later. Because of this, the boys became very close and practically lived together for long periods of time. Although they continued to enjoy playing their old-time music, the two gradually found themselves paying close attention to bluegrass sounds—particularly groups like the Country Gentlemen and the Osborne Brothers. Jimmy and Wes attended Carlton Haney’s 1965 Fincastle, Virginia, festival—considered the first multi-day bluegrass event ever held.

Arnold, who even at this early stage showed promise of his later banjo virtuosity, had become enamored of Don Reno’s picking. To fill out their bluegrass band, a mandolin player was needed so they could have another lead instrument.

“Jimmy taught his cousin Tommy Arnold to play mandolin,” Wes recalls. The usual round of fiddlers’ conventions and local shows continued, but one night around 1966, opportunity knocked—in the person of Bobby Lord. Golding remembers that “We had somehow met Bobby at one of his shows and he liked us and our sound.” The result of this chance encounter with the Nashville singer was an exciting trip to Music City the following summer for Wesley’s young group. “We were guests on Bobby’s early-morning TV show; initially he had thought he could arrange for us to play the Grand Ole Opry, but this attempt was unsuccessful, so we did get to do the Ernest Tubb Record Shop,” smiles Wes. “Also, we were Lord’s guests at the Opry, backstage and everything and we were really excited about getting to do this.”

Back home from Nashville with stars in their eyes, the talented adolescents did their first recording—a 45 rpm—at a Mt. Airy studio. The tunes were an instrumental version of “The World Is Waiting For The Sunrise” and “Make Me A Pallet On The Floor,” both from the Country Gentlemen songbag.

Mandolinist Tommy Arnold quit the band about this time, according to Golding “because of sports and other things a youngster wants to do. I guess me and Jimmy were just die-hard bluegrassers, because we kept hanging in there.”

The next incarnation of Wes Golding’s bluegrass sound was an aggregation known as Jim and Wesley and the Virginia Cutups. This larger unit consisted of Parley Gray on mandolin and Joe Ed King on fiddle in addition to Wes and Jimmy Arnold and Wayne Golding, who had been drafted to play bass fiddle. The addition of Wayne also resulted in a vocal upgrading for the group, for now there were some fine father-son duets, with Wes singing lead under his dad’s distinctive tenor line.

Through connections made by the elder Golding, the band traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, where they recorded an album. This privately produced disc contained twelve cuts ranging from traditional bluegrass songs (“Sitting On Top Of The World,” “Hold Whatcha Got”) to some new bluegrass arrangements of such pop tunes as “Bad Moon” and “Take A Letter Maria.” There were also a couple of instrumentals and a hymn. This LP “sold well for us,” according to Wesley’s recollection and reviews heaped praise on Arnold’s five-string expertise and Golding’s vocal prowess.

The group played radio programs on WPAQ, Mt. Airy, North Carolina, (see BU, August ’87) and a station in Galax, Virginia. “Clyde Johnson was the host for the WPAQ Merry-Go-Round on Saturdays and still is today,” Wes recalls. “It’s a great radio station—they’ve always promoted bluegrass, old-time and all the local talent.” They also played the Galax Fiddlers’ Convention each year, where Golding remembers seeing and hearing such legendary musicians as fiddler Scotty Stoneman.

Another regular venue for the Cutups was Carlton Haney and John Millers’ July festival at Watermelon Park in Berryville, Virginia. “We’d go up there with our families and just spend a whole week. By this time I’d started playing some lead guitar and we were out picking in the field at Berryville one day when Carlton wandered down and heard us,” Wes recalls. “He found a spot for us in the schedule, and after that we always worked his festivals.”

It was at Galax that Jimmy Arnold met fiddler Joe Greene. “Joe was working a lot at that time, so Jimmy started playing some with him,” Golding remembers. “My dad and I then started performing with some different musicians around home.” By the beginning of 1972, Arnold was a member of Cliff Waldron’s New Shades of Grass.

Later the same year, Wesley was offered a job playing guitar with a well-established band, the Shenandoah Cutups. The Cutups, who worked out of Roanoke, Virginia, first contacted Golding while he was still in school. “When I was in high school they asked me if I’d like to pick with them.” Because of educational responsibilities, Wes initially demurred, but did take the position six months later.

His stint with the Cutups was an important milestone in his career as a professional bluegrass musician, and he learned a lot. “It was a big thrill for me to play with guys of that caliber; back then they played about all the festivals. They taught me things about the tightness of a good bluegrass band and the driving aspects of the rhythm.” In the band when Wes joined were Billy Edwards, banjo; Herschel Sizemore, mandolin; Clarence “Tater” Tate, fiddle and John Palmer, bass, although Edwards soon departed and was replaced by banjoist Tom McKinney of Asheville. “At the time, the Cutups were a four-man partnership; I was paid by the day, and took a lot of holidays from school so I could pick.”

While a member of the Shenandoah Cutups, Golding helped them record an album for Rebel records in May and June, 1973. By then he had gotten into songwriting on a larger scale and the band waxed a number of Wesley’s originals including “Still House Hollow” and the Golding-Arnold composition, “Lonesome River” (not the Carter Stanley classic). In September, he was voted third most promising guitar player at the Camp Springs Labor Day Bluegrass Festival.

By autumn of 1973, however, Golding and mandolinist Herschel Sizemore had decided to leave the Cutups and form their own more contemporary group, the Country Grass. “Herschel and I were real close and always in the same vein as far as music was concerned.” Wes recalls. “We wanted to do something a little more contemporary, using more modern material.” By this time Golding was becoming more deeply involved in his own songwriting and was beginning to show promise of the prolific tunesmith that he would later become. Members of the Country Grass included Wes and Wayne Golding, guitar and bass respectively; Herschel Sizemore, mandolin and Tom McKinney, banjo.

Almost immediately the new group made plans for a recording session and in early December, 1973, recorded four tracks at Roy Homer’s Clinton, Maryland, studios for a new album. The LP, released on the Rebel label in 1974 and named ‘‘Livin’ Free” for one of Wesley’s songs, was finished in April, 1974, when eight more sides were recorded. In addition to regular band members, such luminaries as Tom Gray, James Bailey and the young Ricky Skaggs guested on the sessions. This meeting of Skaggs, then with the Country Gentlemen, and Wesley Golding proved highly propitious indeed, for within another two years they would work together.

By Golding’s estimate, Country Grass endured about two years before splitting up. One reason for the split was that anathema of bands—distance. The geographical disparity between members was too great and the logistics of staying together became too much to overcome. With Wayne and Wes now in Cana, Virginia, Herschel in Roanoke, Virginia, and Tom McKinney in Asheville, North Carolina, the distances were prohibitive and the band ultimately folded.

After Country Grass disbanded, Wes came back home and started working for a Mt. Airy hosiery mill, driving a truck. “I started playing locally again, doing the regular fidders’ conventions and shows.”

But he was not destined to remain a truck driver for very long.

It was now late summer 1975. J.D. Crowe and the New South, featuring an assemblage of talent seldom equaled in the annals of bluegrass, had just completed their final tour of Japan. Guitarist Tony Rice would soon depart for California, leaving mainstream bluegrass; at the same time, man- dolinist/fiddler Ricky Skaggs and Dobroist Jerry “Flux” Douglas, who had planned a group of their own, prepared to leave Crowe. Wes got an important phone call.

“I had been to Galax and had gotten home on a Sunday morning,” he remembers vividly. “My mother told me Ricky (Skaggs) had called. My first thoughts were that maybe Rice was leaving J.D. and that maybe that job might be open. I was all up in the air.

But when I called Skaggs back, I found out he wanted me to play guitar in the new band—so it didn’t take me long at all to answer that question!”

Guitarist/vocalist Keith Whitley, Ricky’s old partner from Kentucky, had originally been tapped to work with the new group, but things didn’t work out and Whitley joined another fledgling band, Country Store (which also featured Jimmy Arnold on banjo). Marc Pruett of Asheville was scheduled to play banjo, but was unable to work because of a prior music store commitment. North Carolinian Terry Baucom, slated to join the new band on fiddle (Skaggs had originally planned to play just mandolin), instead was drafted on banjo after admitting to “playing a little” on that instrument. Wes recalls, “I knew Terry played banjo. He was playing around home with people like L.W. Lambert and Charlie Moore. He didn’t have a banjo at the time, but borrowed a lot of banjos around Lexington (Kentucky) for a while.”

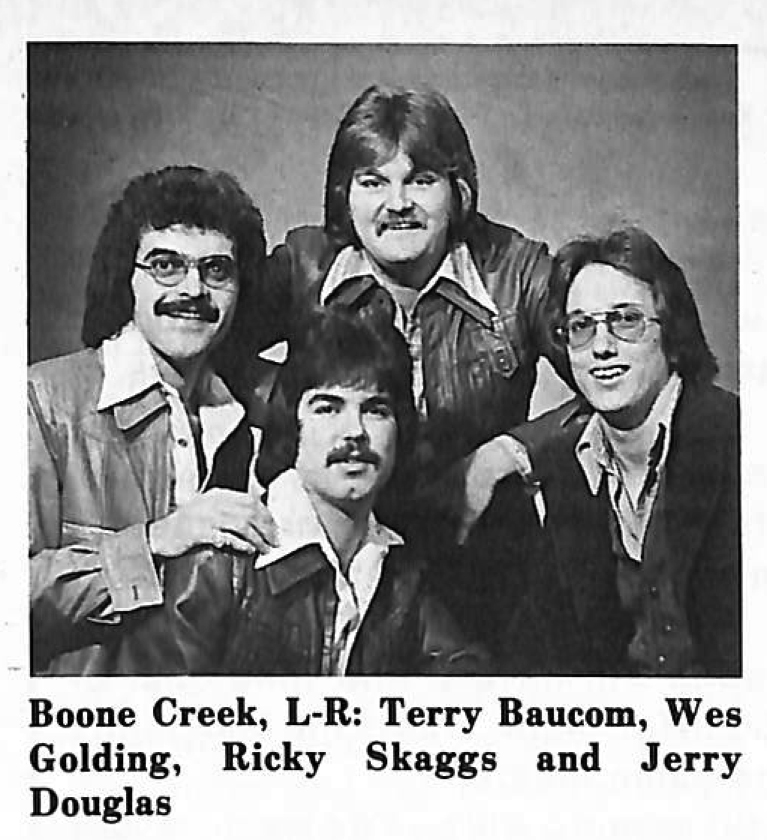

Thus the original members of Boone Creek, formed in September 1975, were Skaggs, mandolin and fiddle; Douglas, Dobro; Baucom, banjo; Golding, guitar and Earl Grigsby, a musician from Kentucky, on electric bass.

The group name was chosen from a song Wes had written about a local creek near Lexington. “From living in Kentucky, Ricky kind of wanted something pertaining to the state for the band name. By then I had learned to love the Lexington area myself, so I wrote ‘Boone Creek’ about a local stream, with some help from our old friend Hugh Sturgill, who helped out with historical aspects and the like,” Golding explains. Skaggs himself paid tribute to Wesley’s uncanny composing abilities: “He writes songs like he’s a hundred years old, like he’s known everything.”

Throughout their career, the members of Boone Creek remained constant except for the bass player. “We had trouble keeping bassists,” Wes recalls with a smile. “After Earl left, we got Tommy Hough and then Steve Bryant.”

Golding recalls that all the band members were close friends. “Everybody lived near each other in an apartment complex in Lexington. Ricky had a lot of connections and he did the booking. We played small places such as bowling alleys when we first started. Hugh Sturgill had some connections with local hotels like Holiday Inns and Sheraton Inns, so that helped a lot.

“I had a Martin D-35 that I had bought in North Carolina, but never really liked it so I used Ricky’s guitar, a ’60s D-28. I got tired of my ’35 so I started playing his a lot.” Somewhat later, Wes was able to acquire the 1946 D-28 herringbone that he still owns. “I bought it from a fellow in a club one night and later had Harry Sparks refinish it for me.”

Boone Creek played Canada a lot. “We would play up around Ottawa, sometimes a month at a time. The snow and cold were unbelievable. I can remember traveling when the temperature was down to zero, we’d go a few miles and the gas line would freeze,” Golding recounts with a grimace. “We kept blankets in the van, though, so we kept warm. We played clubs sometimes for as long as a month at a time, and room and board was included. This of course helped out as far as our expenses were concerned, but waking up in the same place for so long did sort of get monotonous after a while,” Wes recalls.

Two award-winning and highly acclaimed albums were recorded while the band was together. The first, entitled simply “Boone Creek,” appeared on Rounder. The second package, “One Way Track,” (a Skaggs-Golding collaboration) was the first bluegrass LP release for the newly created Sugar Hill label based in Durham, North Carolina.

Boone Creek of course was a contemporary bluegrass band and their jazz and swing influenced style made quite an impression on young Wes Golding. “Everything jelled with respect to rhythm,” he says. “I learned a lot from Ricky and the other band members about different rhythms, although the syncopation did throw me off a little at first,” Golding acknowledges.

The all-star group played its final gig in January, 1978, at the Birchmere Restaurant. With Skaggs leaving to join Emmylou Harris’ Hot Band, the unit fragmented.

While working with Boone Creek at an Annapolis, Maryland, club called Charlie’s West Side, Golding met Trudy Dove, who was one of the group’s biggest fans. She and Wesley were married April 1, 1978, in an outdoor wedding ceremony on the Blue Ridge Parkway during which Jerry Douglas played Dobro on an original Wes Golding song especially for the festive occasion.

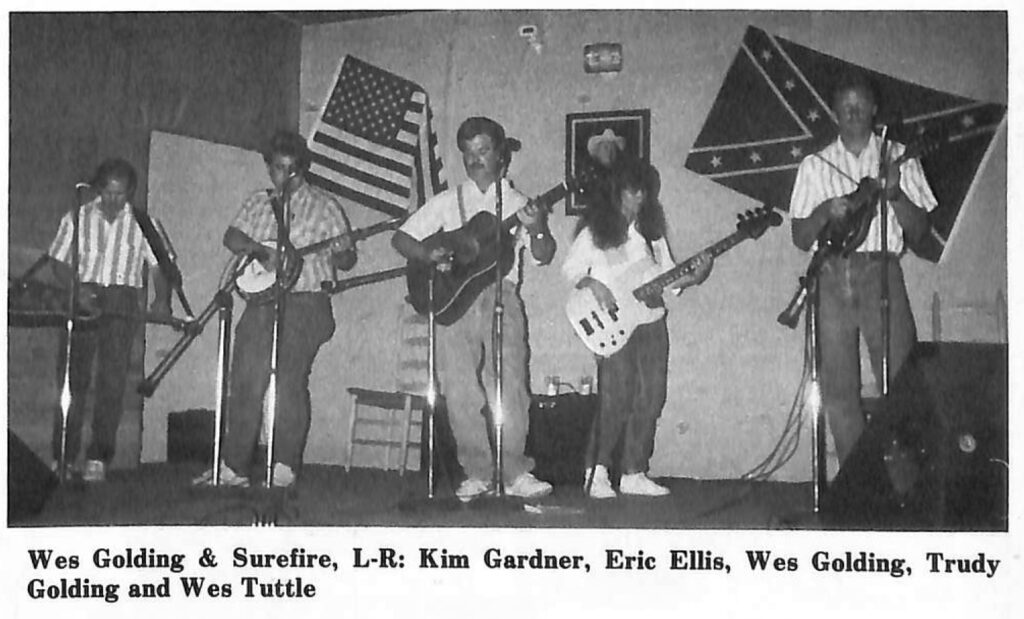

After the Boone Creek breakup, Wes moved back to Mt. Airy where he and a friend operated a music store for about a year. At this emporium he made the acquaintance of Wilkesboro, North Carolina, banjoist Eric Ellis. This led to the formation of Sure Fire, Golding’s current group (named for the Osborne Brothers instrumental). Other group members include Trudy Golding, electric bass; Wes Tuttle, mandolin and Kim Gardner, Dobro.

Sure Fire has released one LP, “River Of Teardrops,” on the Heritage label and is currently at work on a second disc. Wes continues to hone his songwriting. He is well represented on record by such groups as the Virginia Squires, who have recorded several of his best compositions. At this writing, the Seldom Scene plans to wax one of Golding’s songs.

Wes and Trudy now live in Advance, North Carolina, ten miles from Winston-Salem. She is a DJ at WPAQ, Mt. Airy and Wes has a route job for a cookie company. They have a young son, Joshua, who at this writing is interested in the ukelele.

With his powerful lead singing, unique guitar style and a natural talent for writing some of the best contemporary bluegrass material being released today, Wesley Golding will continue to be a major figure in our music.