Home > Articles > The Archives > Jim & Jesse — Reprising Their “Epic” Best

Jim & Jesse — Reprising Their “Epic” Best

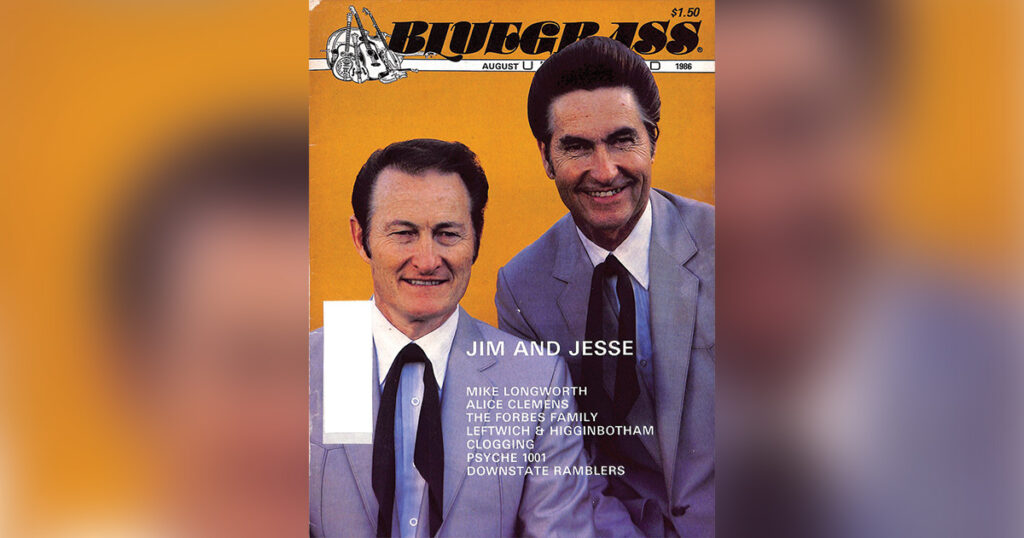

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1986, Volume 21, Number 2

The fine bluegrass Jim and Jesse McReynolds recorded for Epic in the early 1960s and released on albums and 45s has long been out of print in the United States. In the early 1970s Jim and Jesse rereleased in a twin-pak consisting of replicas of “Bluegrass Special” and “Bluegrass Express,” the first two bluegrass albums they recorded for Epic in 1962 and 1963. These have long ago sold out and are collector’s items now. In 1976, “Jim and Jesse With The Virginia Boys, Volume 1” on CBS/SONY 20 AP-19, a Japanese reissue album, featured all the Jim and Jesse singles which were never released in Epic albums. This album unfortunately has not been in wide circulation in the United States. Nevertheless, some of the excellent Epic songs are still re-created on every Jim and Jesse show and have been rerecorded by latter-day Virginia Boys on Jim and Jesse’s many Old Dominion albums.

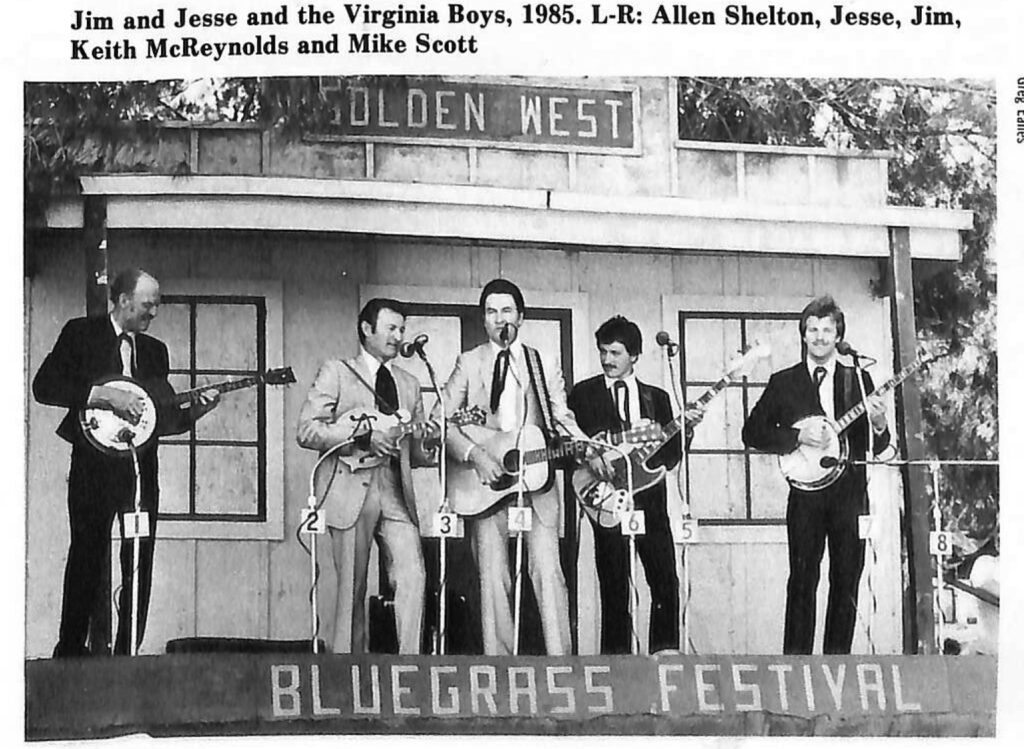

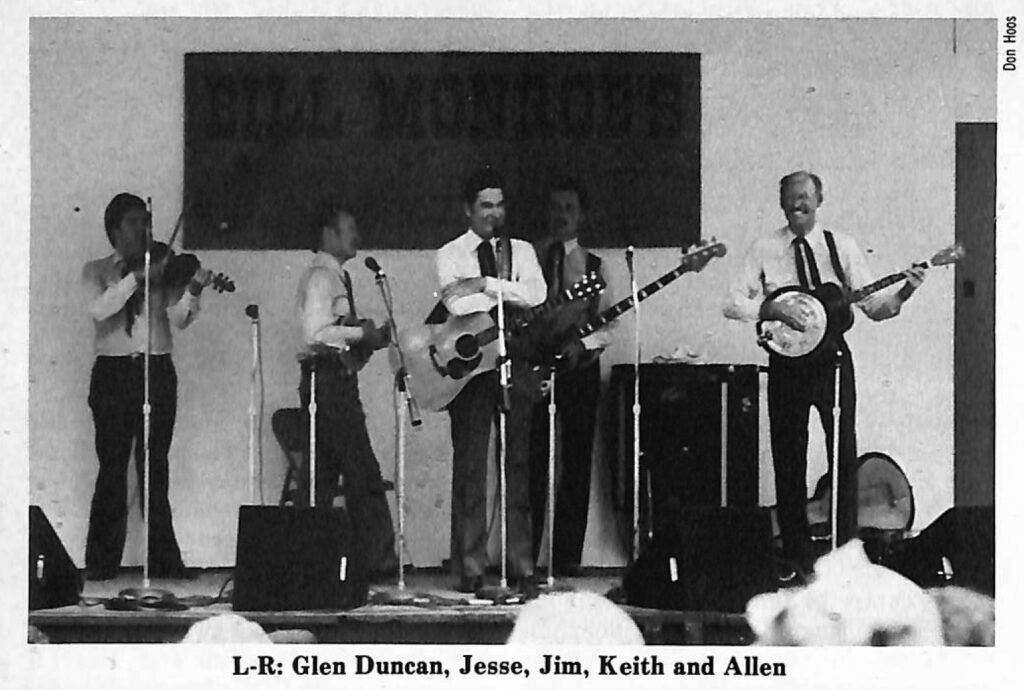

In the fall of 1983, Jim and Jesse had the good fortune to have Allen Shelton return to the Virginia Boys. Allen for a few years played 5-string Dobro to complement the band’s regular banjoist, Mike Scott. With Scott’s departure early in 1986, Allen now handles the 5-string work on both banjo and Dobro. Naturally, some of the old arrangements of the early 1960s are being revitalized in personal appearances by Jim, Jesse, and Allen. To re-create the old arrangements even better, they are occasionally joined on live shows by Jim Buchanan on fiddle, another veteran Virginia Boy of the Epic days, though in recent months Glenn Duncan has been with the band handling the fiddle chores.

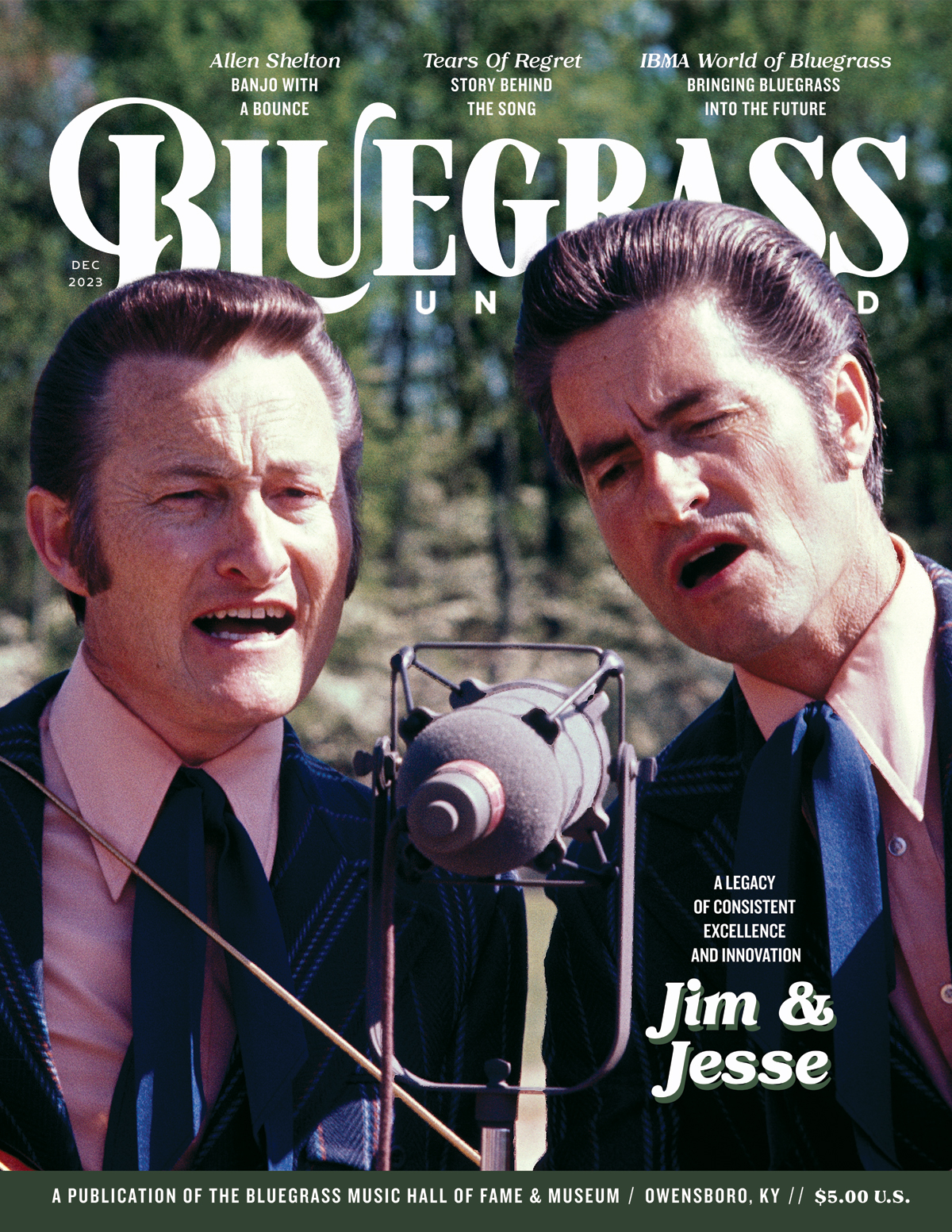

Ken Irwin, Bill Nowlin, Marion Leighton, and their associates at Rounder Records astutely found a need for reissuing the old sounds by this famous band. Some of Jim and Jesse’s most popular songs by this band are now reissued in a new Rounder album, “Jim and Jesse, The Epic Hits,” Rounder Special Series No. 20.

BIOGRAPHY

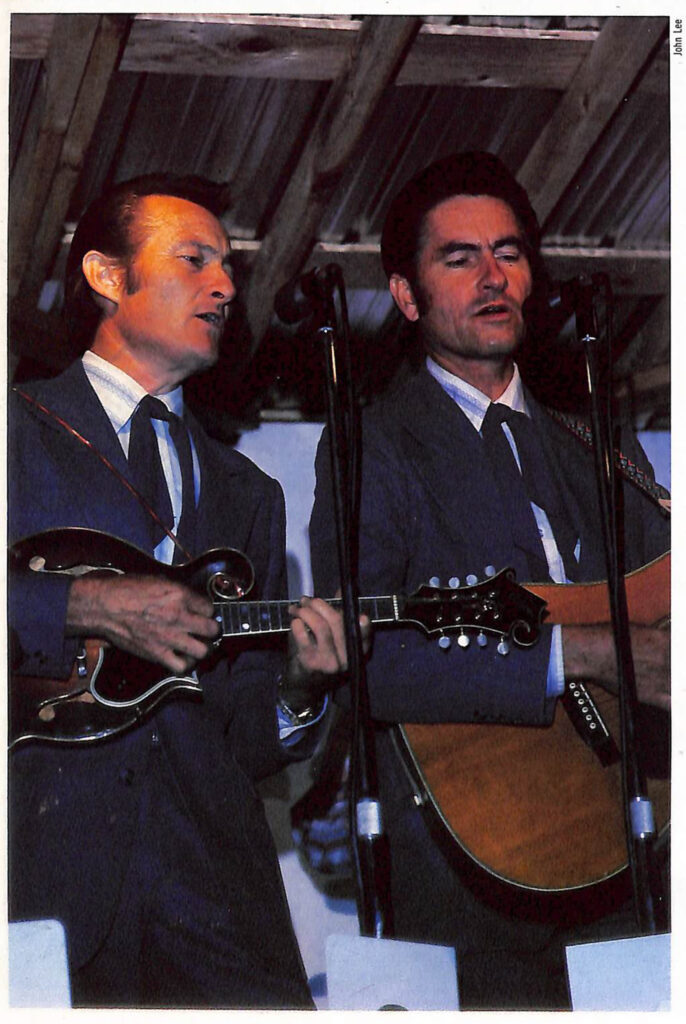

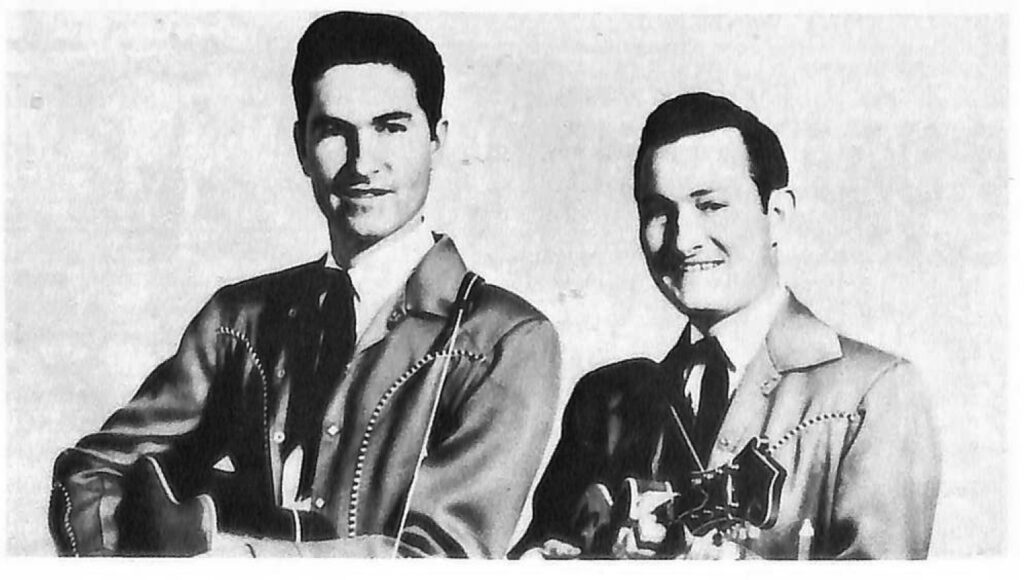

Jim and Jesse McReynolds are the most distinguished, smoothest, and consistent fraternal duet in bluegrass music, featuring consistently superior vocals with lead and tenor harmony. They hold an uncontested record for longevity of a fraternal duet in bluegrass and country music; they debuted professionally in Norton, Virginia, at radio WNVA in 1947. Another of their lasting contributions to bluegrass includes Jesse’s superb abilities as an instrumentalist who originated a new technique for playing mandolin. Their musical acumen and astute management have been demonstrated in their selection of excellent sidemen. Perhaps one of the best configurations of their band, the Virginia Boys of 1963-1964, is showcased on the recently released album.

Both McReynolds brothers hail from Carfax, Virginia, a small town between St. Paul and Coeburn. Jim McReynolds, a rock-solid rhythm guitarist and excellent tenor and high lead singer, was born February 13, 1927. Jesse, innovative mandolin player, lead singer, songwriter, and Master of Ceremonies for their many personal appearances and broadcasts, was born July 9, 1929. Their informal musical education began within the family. Their mother, Savannah Prudence, instilled in her sons a love of gospel music and song; their father, Claude, was a respected local fiddler with talented brothers who played banjo and guitar. Charles McReynolds, their grandfather, significantly influenced the brothers’ appreciation of instrumental music. Charles recorded for Victor with his Bull Mountain Moonshiners in 1927 (just before the Carter Family’s first record). Their brother-in-law, Oakley Greear, a talented local fiddler who let Jesse get acquainted with the mandolin and actively taught him fiddle when he was 14, also provided an important musical role model and mentor relationship. Jim and Jesse experienced a particularly memorable event when they attended a performance by the Carter Family in a nearby Dwina, Virginia, schoolhouse.

Radio broadcasts of the late 1930s and early 1940s helped to deepen and broaden Jim and Jesse’s musical discernment. They remember hearing songs recorded by the Blue Sky Boys, J.E. Mainer, and the Monroe Brothers. They used to listen to live performances by Roy Acuff, Bill Monroe, the Crook Brothers, and the Gully Jumpers on WSM’s Grand Ole Opry on Saturday evenings.

Their formative years were spent learning how to sing and play instruments, but it was their singing prowess which earned wider recognition for them. Their first formal acknowledgment was the first prize they won for close duet vocals with self-accompaniment at an amateur contest in nearby St. Paul, Virginia, in about 1941 or 1942.

Following a separation imposed by World War II, Jim returned from the Army in 1947 with a new Gibson A-50 f-hole mandolin. The brothers resumed their duets with Jesse initially on guitar, but they exchanged instruments after several months to set their present mode of instrumentation. That same year, they formed a four-piece band (with bass and fiddle) and dubbed themselves the McReynolds Brothers, Jesse and James, the Cumberland Mountain Boys. Shortly thereafter, they earned their first daily radio show at midday on WNVA. This show lasted nearly a year, at which time they embarked on a protracted period of quasinomadic life.

The standard operating procedure for small acoustic string bands of the late 1920s through the early 1940s entailed a series of transitory jobs at radio stations throughout the southeastern United States. Program managers were eager to bring in a revolving stable of new talent, but the artists seldom stayed for more than a year, a period considered to be audience saturation point. In exchange, the performing artists could use the radio to literally broadcast their novelty and abilities to new audiences. The performers hoped that members of the radio audience could be attracted to the performers’ personal appearances in different regional locales within the radio station’s listening area. If the performers had records, glossy photographs, or songbooks available, these would be offered for sale. Thus Jim and Jesse began to carry on a process common to their professional musical mentors and counterparts. Their work at WJHL, Johnson City, Tennessee; WCHS, Charleston, West Virginia; WFHG, Bristol; and then in 1949 they began a year’s stay at WGAC, Augusta, Georgia.

In Augusta Jesse developed the essential rudiments of his unique banjolike mandolin roll using only a flat pick. Jesse’s technique consists of emphasizing the upstroke, not the downstroke. That is, he picks the third string of the mandolin with a down stroke, the first string with an upstroke, and concludes the basic formula with an upstroke on the second string. The first set, or E course of paired, unison strings, are often used as the equivalent of the 5th string on a 5-string banjo, sounded open like a “drone” string.

“It’s what we call the backwards roll, the banjo roll. I didn’t really know how the banjo roll went. I’d never seen anybody do it, I’d just heard [it] and was going strictly by sound. At the time, the boy who played banjo with us, Hoke Jenkins, played the banjo that way. He never played the forward roll. He played it backwards and really, I guess, I thought that’s the way it was supposed to go. The way I worked it out, that’s the only way I could do it to any speed.”

Jim and Jesse decided to explore new territory and left the South for the Midwest. Their next station was KXEL, Waterloo, Iowa; followed by WMT, Cedar Rapids, Iowa and then KFBI, Wichita, Kansas. By 1951 they had formed a trio with Larry Roll in Middletown, Ohio, where they performed country, country-western and gospel songs over WPFB on Smoky Ward’s show. Through Ward’s auspices, Jim and Jesse first appeared on television in Dayton, Ohio.

The band name, the Virginia Boys, was originated in 1951 when the trio recorded initially for Gateway Records, in Cincinnati. Ten old-time gospel songs were eventually, released on Kentucky singles. For the first time Jesse’s innovative crosspicking, which would later become known eponymously as “McReynolds’ style,” could be heard in early stages of development on some of these recorded numbers. All ten songs were reissued on an album about 1961, “Sacred Songs of The Virginia Trio,” Ultra-Sonic records LP 52.

In retrospect, this was the first instance of a recurring sense of proprietary disenfranchisement. Jesse feels that he and Jim would have fared better from the fruits of their artistic efforts if they had been able to gain possession, hence gain control, of the masters from the Gateway session. Jesse reports that these masters have been sold several times to other owners who re-pressed and sold them without Jim and Jesse’s permission and without paying them any royalties. Jesse still suspects that this material is presently available in LP form on budget labels.

Jim and Jesse proceeded to WWNC, Asheville, North Carolina, for a short time before going on to the Kentucky Barn Dance in Lexington and a successful stint at WVLK, Versailles, Kentucky.

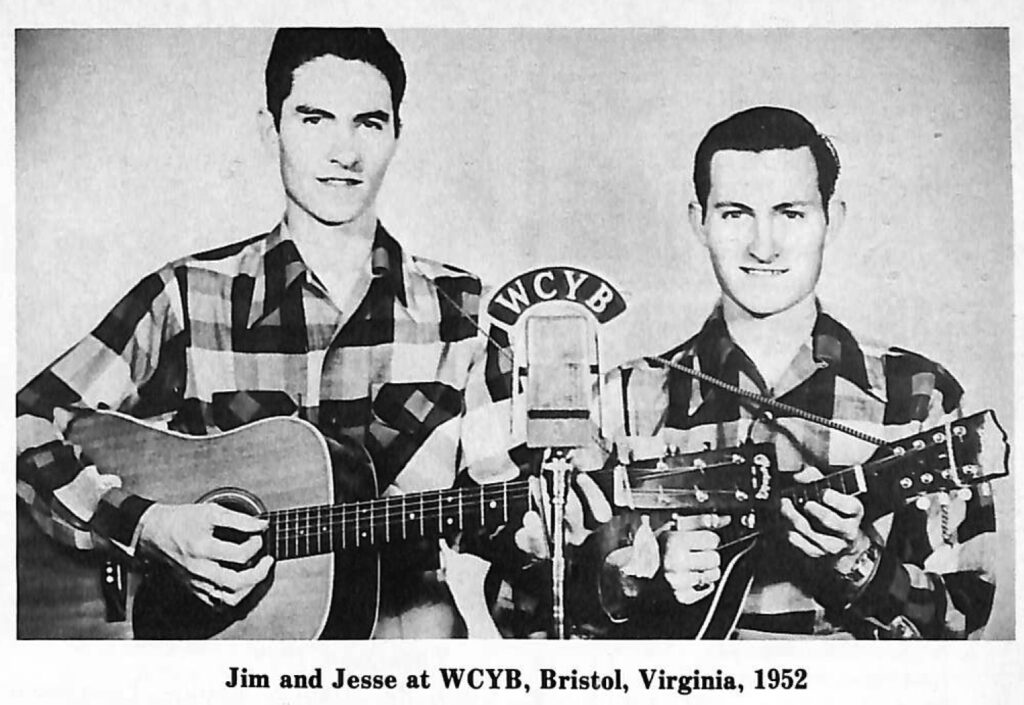

In 1952 Ken Nelson secured a contract for Jim and Jesse to record on Capitol Records, their first major label and their first recordings as a bluegrass band. It was Ken Nelson who suggested “Jim and Jesse” become their new professional name; hence, the first releases on Capitol in October 1952 bore the new name. Jim and Jesse then moved to Bristol to join WCYB’s Farm and Fun Time; there they sang duets on their own 15-minute segment.

At this point, the Korean War interrupted their career. Jesse was drafted into the Army on December 2,1952. Before eventually being shipped out to Korea, he and Jim managed to fit in a second recording session for Capitol in Nashville on March 16, 1953. “A Memory Of You” backed with “Too Many Tears” (F-3141 [45-11258]; re-released ca. 1969 as part of “20 Great Songs by Jim and Jesse, Cap. DTBB-264, now out of print) was musically some of the best of all the releases of the Capitol contract. This session also evinced a fully developed McReynolds style mandolin.

While stationed in the Yulang-gu Valley of Korea, Jesse was assigned to the Army’s local Special Services unit. There he had the good fortune to meet and play country music with Charlie Louvin of the Louvin Brothers, another fraternal duet also separated by the war and one which Jim and Jesse highly regarded and have consistently emulated.

Late in 1954 Jesse was discharged. He and Jim quickly reformed the Virginia Boys and located in Danville, Virginia. For a short time they appeared regularly on the WDVA Barndance, as well as on early morning and mid-day shows. An even shorter engagement on WBBB in Burlington, North Carolina, was followed by Lowell Blanchard’s invitation to join WNOX’s well-known Midday Merry-Go-Round and Tennessee Barndance, in Knoxville, Tennessee.

By midsummer 1955, Jim and Jesse had joined the prestigious World’s Original Jamboree on 50,000 watt WWVA in Wheeling, West Virginia. Hylo Brown often performed with Jim and Jesse at personal appearances that summer. While it was to the brothers’ advantage to be on a 50,000 watt station, WWVA’s antenna beamed its powerful signal northward into the Great Lakes states, New England, and Canada. Severe winter months and hazardous road conditions in the WWVA northerly audience area influenced Jim and Jesse’s choice to return to the Deep South. In November 1955 they relocated in Live Oak, Florida, where they joined the Suwanee River Jamboree and performed daily on WNER. In order to survive financially in an era when rock and roll’s immense popularity was luring away country music’s audience, they further extended themselves by traveling with the radio troupe’s package shows. Jim and Jesse also participated in their first audio-taped syndication of radio shows with the WNER troupe as country musicians tenaciously attempted to maintain their audience —and careers.

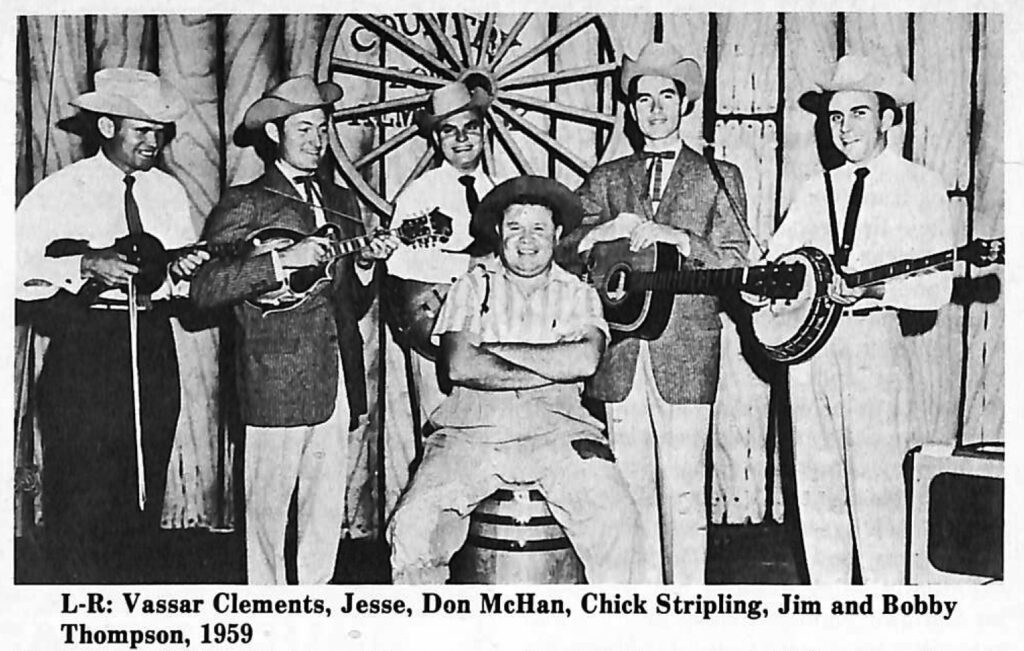

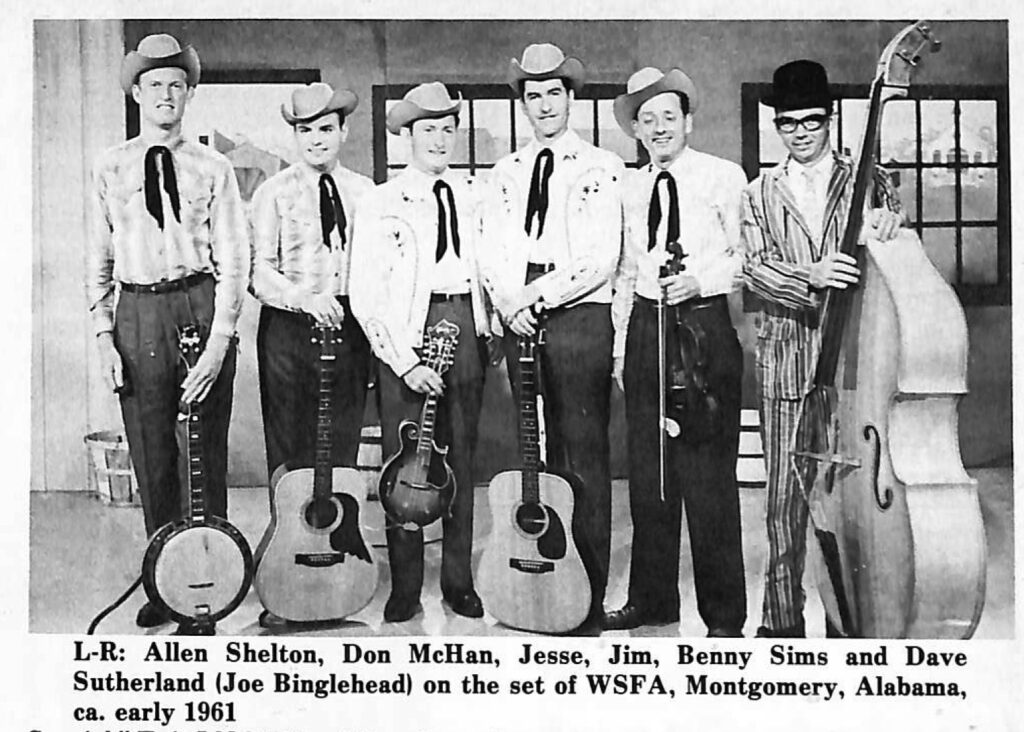

Jim and Jesse have always presented themselves well on television. They secured their first 30-minute television show in about 1956, on WCTV, Tallahassee, Florida. Other slots subsequently included WSAV-TV, Savannah, and WALB-TV, Albany, Georgia. By 1957 they had formed the first of their most popular bands, consisting of Vassar Clements, fiddle; Bobby Thompson, 5-string banjo; Don McHan, electric bass; and Chick Stripling, comedian and acoustic bass player. This band appeared on yet another live show over WEAR- TV, Pensacola, Florida. By 1958 they also played weekly on WTVY-TV, Dothan, Alabama. Jim and Jesse’s bluegrass by 1961 was also aired on WSFA-TV, Montgomery, Alabama, and WJTV, Jackson, Mississippi. Around 1961 or 1962 they began videotaping their shows in Jackson for select distribution to farther- flung stations to reduce their driving distance of 1,300 miles per week.

In 1958 Jim and Jesse signed a recording contract with Don Pierce of Starday Records who agreed to distribute their music. Jim and Jesse, however, were obliged to produce and record their own masters at an independent studio in Jacksonville, Florida, then leased them to Don Pierce. The first Starday releases were in 1959. Re- release and reissues of these masters have continued unabated since then, beyond Jim and Jesse’s control and, again, with no royalties. In this same year they also became stars of the Lowndes County Jamboree on WGOV, Valdosta, Georgia.

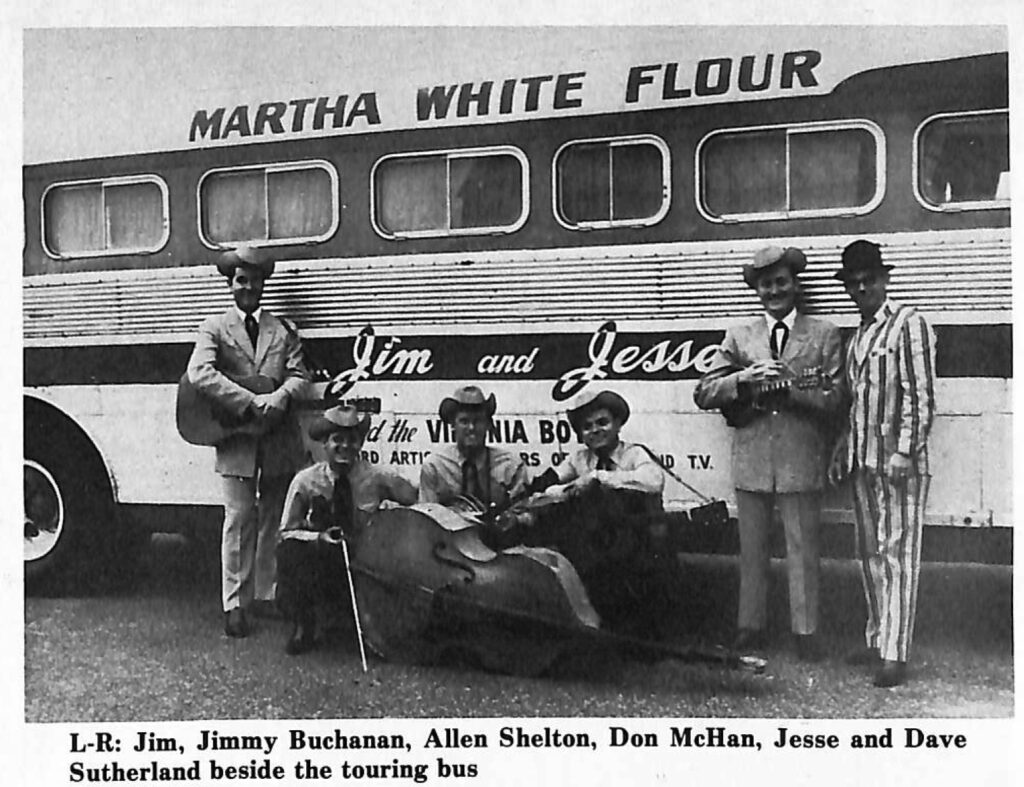

In 1960 Jim and Jesse signed a contract with Martha White Mills, beginning a very happy association which was to last five years. Martha White became a co-sponsor of their television shows in Georgia, Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi. Beginning in early 1961 Jim and Jesse began taping the Martha White daily, 15-minute, radio shows at WGOV for airplay elsewhere, notably on WSM at 5:45 a.m. This program was formerly the exclusive showcase of Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs.

Columbia-Epic Records

In October 1960 Jim and Jesse at tended the annual D.J. convention in Nashville with A.O. Stinson, then advertising manager of Martha White Mills. Stinson was able to interest Don Law, A&R executive with Columbia Records, in Jim and Jesse’s commercial appeal and informed Law of the brothers’ disenchantment with the arrangement they had with Starday Records. Stinson set up a successful meeting of the two parties at the convention. A Columbia contract was extended to Jim and Jesse by Don Law on December 1, 1960.

In 1960 Columbia was designing a country division for their subsidiary, Epic Records. Jim and Jesse signed with Columbia for an indefinite period of recording and releasing on Columbia until the country stable of Epic was sufficiently developed and coordinated for promotion. Other conventional contractual stipulations included the required release of two singles a year and flexible conditions for recording material for an album as time and availability permitted. Law evidently was very eager to test Jim and Jesse’s marketability for he rushed them into the Owen Bradley studios on December 7, 1960 for their initial session. The single of “Flame Of Love” and “Gosh, I Miss You All The Time” (Col. 4-41938 [ZSP 52752, 52751]) was manufactured rapidly and released in January 1961 amid fanfare and publicity generated by Columbia Records. The brothers performed extensively on WSM, clear channel 650 with 50,000 watts of transmitter power, aptly named, “Air Castle of the South,” for it could be heard for 500 miles radius in any direction-under favorable weather conditions. Their publicity appearances on WSM included a guest spot on Mr. D.J. U.S.A. and on Ralph Emery’s late night Opry Star Spotlite on January 27, 1961. The following evening they performed for the first time as guests on WSM’s famed Grand Ole Opry, and a few hours later on Ernest Tubb’s Midnight Jamboree.

Jim and Jesse’s second release of a Columbia single was in October, 1961. This release coincided with their guest appearance on the Grand Ole Opry, October 1,1961. Shortly thereafter, Columbia executives were ready to publicize their new country roster on Epic. In the meantime, Jim and Jesse had become displeased with Columbia’s publicity of themselves and their music. For example, Jim and Jesse were not overly enthused about their identities being submerged in packaged promotions among several Columbia country artists in Billboard. They felt their bluegrass was distinct from the contemporary country stylings and instrumentations. Don Law offered them an opportunity to remain on the Columbia label, but he advised them to join a new roster and reap the benefits of the anticipated promotional effort to make Epic’s country division a success. It was also considered prudent to avoid too much competition —and apparent conflict—with existing Columbia artists.

Jim and Jesse moved to Epic in early 1962. Don Law introduced them to Frank Jones, a newcomer to Columbia and executive-in-charge of producing Epic’s country artists. They soon began work on their first album, “Bluegrass Special,” Epic LN 24031, while collaterally releasing two singles in March (“Stormy Horizons” b/w “My Empty Arms,” Epic 5-9508 [ZSP 56677, 56678]) and June (“Sweet Little Miss Blue Eyes” b/w “Pickin’ and a-Grinnin’,” Epic 5-9528 [ZSP 57682-1B, 57683-1B]). Because of their own ceaseless efforts, the benefits of a major sponsor and major label, the resurgency of country music after Elvis, and the rise of the American folk music revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s, Jim and Jesse were becoming well known and officially recognized; for 1962 Cask Box rated Jim and Jesse third and Billboard ninth in the category of favorite small group.

Jim and Jesse recalled they selected the material for inclusion on the Epic sessions. For the sessions produced by Don Law, the brothers would bring their material to Law’s office the day before the session. Law, Grady Martin, session leader and Law’s assistant, and Jim and Jesse would choose which songs to schedule the following day. According to Jesse, Law abided by the duo’s selections and never vetoed them. Law’s role was to achieve the best production possible once they were in the studio.

Jim and Jesse selected the material for “Bluegrass Special” and their second Epic album, “Bluegrass Classics,” mostly by reprising songs they had been singing for years and which fit bluegrass stylings well, in addition to newer material they had thoroughly rehearsed on the road and tested on their weekly half-hour television shows in Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, and Dothan, Alabama. Jim Buchanan, their fiddler for many of the Epic releases, summed up the selection process: “Find things that say it best, try it (prove it), then record it.”

On February 26, 1963 “Bluegrass Special” was released, co-produced by Don Law and Frank Jones, though the latter was in charge. Five selections* from this LP are showcased in “Jim and Jesse: The Bluegrass Epic Hits.” The Virginia Boys then consisted of Allen Shelton, 5-string banjo; Jim Buchanan, fiddle; Junior Huskey, bass player for the sessions (David Sutherland was bassist for the road band); and Don McHan, occasional lead guitar and some vocals. Jim and Jesse, as well as Allen Shelton, rank this band as the pre-eminent configuration of the Virginia Boys.

The summer of 1963 was a watershed year for Jim and Jesse. Traditional southeastern bluegrass artists were gaining recognition in the recent American folk music revival. The Virginia Boys were highly acclaimed at the nationally renowned Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island. (Jim Buchanan cites this Newport event as the single- most memorable of his stay with the band.) As a Jesuit of unexpectedly favorable sales of “Bluegrass Special,” Jim and Jesse recorded “Bluegrass Classics” on June 26-27,1963, with Jerry Kennedy replacing Frank Jones as producer. On September 16, 1963, “Bluegrass Classics” was released as Epic LN 24074, four selections from which are included on the Rounder reissue.** The band’s personnel was the same as above, but this time David Sutherland (aka Joe Binglehead, comedian) played bass on the sessions. (* ** See Detailed Annotation to Songs.)

Jim and Jesse’s greatest ambition was realized on March 2,1964 when they were invited to become members of the Grand Ole Opry; on March 7, they played the Opry for the first time as members. Jim and Jesse thus became the first bluegrass band to have been elected to the Opry since Flatt & Scruggs joined in 1955.

During the same year they achieved their status as acclaimed member-artists on the Opry, Jim and Jesse began moving away from their commitment to unqualified bluegrass arrangements. Their recording instrumentation began to change by substituting some of the bluegrass instruments with contemporary electric guitars and steel guitars. Studio musicians closely associated with the Nashville Sound replaced regular band members on recording sessions. As a partial result, their general style became more country in arrangement and sound than that of the preceding decade. The song material itself was more recently written rather than relying on old favorites they learned from their youth and early musichood.

These changes to a more modern country sound may not have been a matter of pure coincidence; in 1964 Epic assigned them yet another new A & R man, Billy Sherrill. Sherrill was a dynamic, active executive with astute perceptions of commercial appeal. He stayed with Epic and with Jim and Jesse for the duration of their contract and was influential in their change of musical direction. Sherrill produced Jim and Jesse’s fifth single on March 2, 1964, “Cotton Mill Man” backed with “It’s a Long, Long Way To The Top Of The World,” Epic 5-9676 (ZSP 77261-1E, 77262-ID). Jim Brock had replaced Jim Buchanan on fiddle and Don McHan had relinquished session work in late 1963. This single was released on April 10, 1964. Jim and Jesse were well aware at the time that this single was different from their previous fare. Their partial uncertainty and reserve was soon forgotten. “Cotton Mill Man” sold more copies than any of their prior bluegrass numbers. This sales feat was to be exceeded during their Columbia-Epic days only by their topical novelty song, “Diesel On My Tail,” Epic 5-10138 (JZSP117507) backed with “All For The Love Of A Girl” (JZSP 117506), the former gaining Jim and Jesse their first Top Twenty chart rating (Billboard) in 1967.

Chronologically, the most recent Epic release on the Rounder reissue is a gospel song, “It’s A Lonesome Road.” It has always been de rigueur for Jim and Jesse to include one or more gospel selections on every personal appearance; this sacred song was a staple on their television shows before being released June 22, 1964 on “The Old Country Church,” Epic LN 24107, an all-gospel album conceived and produced by Billy Sherrill.

Detailed Annotations to Songs

Selection criteria for sequencing, or “programming,” an album of the Epic songs were categorized according to objective and subjective criteria. Objective criteria consisted of a song/tune which: (1) had been recorded on or released by Epic Records; (2) had standard bluegrass instrumentation; (3) represented the most popular material of Jim and Jesse’s repertoire. Subjective criteria included the song/tune material: Each cut should (1) feel and sound good (i.e., good material, exemplary performance, standout parts by band members); (2) be preferred by the musicians themselves; (3) meet the concept of proper balance for a sampler or anthology album, encompassing the best representative selections from Jim and Jesse’s overall Epic bluegrass repertoire; and (4), and least importantly, lend itself to adequate pacing from one track to another to show different musical aspects (e.g., tempo, timing, thematic material, styles).

In keeping with the author’s criteria for an album of this type, selections for the Rounder LP were made by the author after a study of Jim and Jesse’s performances of songs from audio-taped “air checks” of part or all of 67 combined radio, television, and personal appearances he or others made from late 1961 to April, 1983. Most of these air checks originated from 30-minute shows on WTVY-TV, Dothan, Alabama, and WEAR-TV, Pensacola, Florida, while the author was living in Panama City, Florida, in 1963 and 1964. A total of 453 songs or tunes were reviewed in this selection process which yielded an index of relative popularity, represented by a scale from 1 to 7, the total number of performances of a single title. Bracketed numbers after each title below refer to the frequency of airplays. That is, out of a total of 453 numbers reviewed, a [5] indicates that a particular number was played five times. While not an infallible index of popularity, the frequency with which the top songs repeated is some raw measure of audience — as well as Jim and Jesse’s — preference for select songs. Thus, many of the selections on this album were included because of the persistence of these songs on live shows. Notably, “Slew Foot,” a comic novelty song (not on the Rounder album), was performed the most: seven times. The fact that their recorded numbers did not occur more frequently is an indication of the great breadth and depth of repertoire Jim and Jesse could deliver in their live performances and that they did not overemphasize, or “hype,” their recently recorded songs to the exclusion of other material.

Reference to the key of each song is enclosed within parentheses. Credit to composer(s), when identifiable, is often given in the second parenthetical enclosure. For example, “Take My Ring From Your Finger,” (key = D), [6] six documented live plays from a total of 67 shows, 1961-63, written by the (Louvin Brothers).

**“Nine Pound Hammer” (B) [3] is attributed to the late, legendary guitarist from Western Kentucky, Merle Travis, though it is much older. Flatt and Scruggs had played this song as early as February 3, 1956 on the Martha White show on WSM, but did not play it often until the folk music revival, beginning with personal appearances before semi- urban and urban audiences 1960-1962, then in 1963 and 1964 frequently on the Opry. Jim and Jesse’s version is an epitome of hard-driving bluegrass, with Allen Shelton’s exceptional sparking power propelling the song.

Allen recalls Jim and Jesse brought this number to the Bradley studio on June 26,1963 to work it up for the recording session that day. Jim and Jesse had generally brought in songs which had been proven popular during their personal and media appearances, so this was an exception to the tried and true repertoire usually used in sessions at this time. Doubtless, this selection was designed to appeal to the folk music enthusiasts who were then increasingly attracted to bluegrass. Jim and Jesse changed the chordal structure from the I, IV, I, V, I in the first half of the strain to a progression of I, IV, V so that both halves of the strain had identical structural form. Jim and Jesse are proud of this arrangement. The vocal antiphony used in this arrangement of “Nine Pound Hammer” likely began with Charles Bowman. Bowman taught it to his fellow members of the Buckle Busters string band in May, 1927 for their recording on Brunswick Records in New York City (Brunswick #177). Jim and Jesse probably were more directly influenced by the Monroe Brothers’ version of “Nine Pound Hammer,” recorded in 1936 and released as Bluebird 6422. The Monroes’ arrangement is nearly identical to the one heard on the LP. That is, Jesse sings the phrase first in melody lead, then Jim sings the same phrase in tenor harmony. After the first three phrases are sung an- tiphonally, Jim and Jesse sing melody and tenor together for the fourth, concluding phrase. Structurally, it looks like this:

Roll on, buddy (Jesse, LV)

Roll on, buddy (Jim, TV)

Won’t you roll so slow (Jesse, LV)

Won’t you roll so slow (Jim, TV)

How can you roll (Jesse, LV)

How can you roll (Jim, TV)

When the wheels won’t go. (Jim and Jesse together, LV & TV)

One of Allen’s favorites, he remembers learning his break while running down the arrangement with Jim and Jesse in 30 minutes.

*“Are You Missing Me?” (G) [4] was penned by Ira and Charlie Louvin; it has been a mainstay in Jim and Jesse’s repertoire since they recorded it initially for Capitol on June 13, 1952 (Cap. F-2233 [45-10144]). The Epic variation of the song was recorded June 22, 1962.

This song has two of the archtypical chordal structures of traditional bluegrass verse: I, IV, I, V/I, IV, I, V, I; chorus: I, V, I/I, V, I. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, this song was re-created by many other bluegrass groups and was indeed a bluegrass standard for 5 years or more. Allen’s banjo break exemplifies one of his musical credos: “Just try to play melody. I stay [with the] melody if I can.”

*“It’s A Long, Long Way To The Top Of The World” (B) [5] (D. Wayne) is a medium tempo, waltz-time lyric, recorded March 2,1964, and released April 10, 1964. It represents the beginning of a transition away from the full bluegrass sound established by Jim and Jesse toward a more country sound.

At any rate, for Jim and Jesse the transition represented an appeal to a larger, somewhat different audience of mainstream country music, as well as possibly a partial response to the fickle members of the waning audience of the folk music revival, many of whom were entering the era of social relevance and skepticism, personified by folk-rock giant, Bob Dylan. One way in which this transition is detectable in the words is in the truism embodied in the refrain, which self-consciously pleads in abstractions for universality —songwriting designed to offend no one in the John D. Loudermilk school of Nashville writing. The refrain follows: It’s a long, long way to the top of the world/But it’s only a short fall back down. Allen says he tried his best to put the prettiest backup he could into this song. It is still one of Allen’s favorite Jim and Jesse songs, although they don’t perform it much anymore “because it’s so ‘old.’ ”

♦The preceding song was backed with “Cotton Mill Man” (F) [4] (Joe Langston); recording and release dates are identical with the preceding tune. This song has become permanently associated with Jim and Jesse as a remarkable bluegrass statement of socioeconomic industrial consciousness. The social realism described in this musical indictment of working conditions in and dependency on cotton mills and their deplorable system of company houses and stores is atypical of Jim and Jesse’s repertoire. Jim and Jesse’s protest of Kentucky strip-mining practices in “Paradise,” their only Opryland single (3832 in 1974), vies for similar humanitarian, as well as ecological, honors. This Epic arrangement features a structure and melody also atypical for bluegrass performers of the day. The bridge is an especially powerful blending of music and text as the specific injustices are hammered home by Jim’s trenchant tenor. This song is one of Allen’s all-time favorites.

“Cotton Mill Man” was written by Alabaman Joe Langston, who was then a songwriter in Nashville. Langston had taken his song to Joe Taylor, an independent booking agent, formerly successor to A.O. Stinson, advertising manager for Martha White. As agent for Martha White, he learned about the repertoire and sound Jim and Jesse had developed. Taylor suggested Jim and Jesse adopt this song, leaving with them a demonstration tape of Langston, self- accompanied with guitar, from which to learn. Jim and Jesse learned quickly from the demo tape, with Allen Shelton learning right along with them. And they learned it to perfection; no individual or bluegrass team has been able to approach this stirring song with the intensity invested in it by Jim and Jesse’s delivery. Allen considers this the first musical highlight of his early career as a Virginia Boy. He remembers in the recording studio it had a special “knock” to it which he knew at the time constituted a good cut.

The genre of protest song was a new undertaking for Jim and Jesse. Jesse stated in an interview with the author that although they had not actually worked in cotton mills, many of their “… people have, around Kingsport, Tennessee. But as far as a real-life connection with cotton mills, we don’t have any.” Jim and Jesse were not espousing a cause per se, but the debasing conditions of a typical cotton mill system portrayed in “Cotton Mill Man” fell on receptive ears among members of their audience. Jesse related some of the mixed reaction: “There was a few radio stations that hesitated to play this song, especially in towns where they had a lot of cotton mills. As far as doin’ it on television, we used to do it a lot in Dothan, Alabama, and the [other] shows we were doin’ on television down there. We got a few letters suggestin’ that we not sing this type of song, but it was very few. Why, overall, most people like the song pretty well.” And so they did; at the time, it was their most successful single and it is consistently requested to this day at their personal appearances.

*“She Left Me Standing On The Mountain” (G) [4] (Alton Delmore), recorded April 22, 1962, is a medium-to- fast quasihumorous song which gained appeal among members of Jim and Jesse’s television audience in the Deep South. Allen worked out a banjo solo to achieve “as much drive as I can get.” He prefers to forsake the exact melody line if there is an appropriate place to punch hard with a straight, driving sequence of traditional index-finger lead right-hand rolls.

♦♦“Take My Ring From Your Finger” (D), [6] was written by the Louvin Brothers. Recorded June 27, 1963, it is an outstanding, propelling example of Jim and Jesse’s quintessential brand of smooth, confident bluegrass, a veritable juggernaut of bluegrass music.

Jim and Jesse learned this song from a recording by Johnny and Jack and the Tennessee Mountain Boys years ago (RCA Victor 21-0448B —Recorded at WSOC, Charlotte, North Carolina Oc tober 17,1950). They have been singing it continuously ever since. Their regard for the song is amply demonstrated by the power and precision with which they sing it. Allen felt that their singing was so impelling during the recording session that it set the level of excitement for the other band members as well.

| R. Hand: | TIM | TIM | TIM | TIM | IT |

| Strings: | 432 | 321 | 432 | 321 | » 23 |

| Fret: | 023 | 234 | 023 | 234 | 32 |

Allen related the technicalities he experienced in this arrangement. It was difficult to play in the key of D (banjo tuned to open G, 5th string tuned up to A), especially the “inside ranges.” Because the “melody held straight” for the first 4 bars, he could use the inside roll of for the third and fourth bars, which he had previously developed while learning how to play Chet Atkins-style guitar. He ingeniously adapted the Atkins guitar technique to the 5-string banjo. Because of the expanse of the melodic range, he felt he couldn’t use a capo for he needed the wide-open neck for complete access to all the notes he needed. For all of the above reasons, Allen still ranks this song as one of his all-time favorites.

*“Don’t Say Goodbye If You Love Me” (A) [5] (J. Davis and B. Dodd), recorded in the 1930s by the Blue Sky Boys, is a medium-to-fast country love lyric, featuring Jim’s soaring tenor on the first phrase of the chorus. Recorded on June 22, 1962, it is typical of the Jim and Jesse bluegrass sound.

♦♦“Drifting And Dreamin’ Of You” (B) [2] was written by Jesse in 1953 when he was stationed in Korea. Recorded on June 27, 1963, it was also released on a single, Epic 5-9635 (JZSP76329-1E). This is one of the few songs Jim and Jesse perform with a high lead by Jim, an inversion of the lead vocal part with the melody voice on top of the stacked harmony, instead of on the bottom. This harmonic configuration-style was championed by the Osborne Brothers, the first example of which was “Once More,” recorded in July 1957. Although Jesse disclaims he had anyone in mind as the object of this beautiful, haunting song at the time, he does say he wrote it “maybe because I was a long way from home and it was a little different song…”

This song is one of Jim Buchanan’s most favored as a Virginia Boy. Jim and the idea of using the instrumental antiphony with a deep echo chamber and so personally took the initiative to arrange with the studio engineer to achieve this remarkable, complementary contrast.

♦“Stoney Creek” (A) [3] is a fiddle tune Jesse wrote, which was based on a tune he learned from his father, one of only two instrumentals with bluegrass instrumentation recorded and released on Epic, both of which recorded on June 22, 1962. Frank Jones suggested they include it in “Bluegrass Special” to show the breadth and depth of the brothers and their band. Jim Buchanan helped define the unusual structure of the second part, which initially involves a modulation from the tonic of A to a temporary tonic of F; the entire progression of the second part then proceeds as follows: F, Dm, F, Dm, F, Dm (C), F/F, Dm, F, Dm, F, E. “Stoney Creek” became incorporated into standard repertoires.

Allen recalls he had worked out several different breaks to this tune, as was his custom for instrumentals and contemporary country songs. Jesse did not know which variant Allen preferred, but unerringly chose the break heard on the Rounder LP as the most appropriate for the tune. Allen cites this anecdote—one among many —as evidence of his and Jim & Jesse’s similar musical tastes, preferences, and standards of excellence.

**“Why Not confess?” (E) [1] (Ralph “Zeke” Hamrick, of the Hamrick Brothers) was recorded in 1940 by the Blue Sky Boys. It is an up-tempo waltz popularized by the Louvin Brothers. Recorded on June 27, 1963, it features Jim and Jesse’s characteristic fraternal vocal duet together with Allen’s excellent banjo break and fills. Allen’s years of experience with Jim Eanes whose forte was slow, danceable country numbers, allowed Allen to perfect his “country banjo” backup techniques, many of which were inspired by the commercial country music solos and fills developed by contemporary Nashville pedal steel guitarists. Allen’s masterful mixture of bluegrass banjo and adapted pedal steel techniques is amply exemplified here, despite the fact that for banjo pickers it is in the relatively difficult key of E (here played with capo on 2nd fret, chorded in D).

*“I Wish You Knew” (B) [5] was also written by the Louvin Brothers. Recorded June 22, 1962, it is one of two of Jesse’s most favorite Louvin songs he and Jim recorded during the Epic bluegrass years. This song is partial evidence of Jim and Jesse’s mixed approach to elements of bluegrass repertoire; the verses are more or less standard, expectable, repeated sets of 8 bars each, but the chorus is metrically unbalanced with the verses and is unusually long—24 bars —compared to the more conventional bluegrass choruses of the day, which averaged 16 bars. This driving song has been synonymous with Jim and Jesse and has become the song most often adopted from their repertoire by emulators. Jesse relates his combined affinity for songs penned by the Louvins and his interest in country material which would appeal (i.e., be identifiable with a larger musical context) and be au courant with his audience. “We first heard it when they had a single record out on it when we lived in Georgia. We were doin’ television shows at that time, so we had to keep up with, really, what was cornin’ out on record. It happened to be a good record at that time by the Louvin Brothers, and that’s why we picked it up and started doin’ it, bluegrass style.”

“It’s A Lonesome Road” (B) [5] (Reeves), recorded April 20, 1964, is one of the ‘grassiest gospel songs the Virginia Boys perform as a quartet, second only, in my opinion, to “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” Jim and Jesse used to sing at least one gospel song on every show, so it is appropriate to include one on an anthology to balance the selection. Notable is (1) the absence of a fiddle and (2) an audibly perceivable sense of controlled restraint, indicative of a tradition of reduced instrumentation and increased reverence and respect in the performance of gospel songs. Jesse sings the verses in his lowest register, a high bass part, then shifts to a higher register for lead in the chorus. This song was a staple on Jim and Jesse’s television shows before being originally released in late 1964.

Jim and Jesse’s bluegrass sound came of age during the Epic years 1963-1964. It was during this time that they were able to transcend their original regional audience in the Deep South and broaden their marketability. Without sacrificing their regional proponents and musical affiliations, they developed a successful combination of traditional, derived-from-traditional, and contemporary songs which appealed to a broad cross-section of the American musical audience who liked folk, gospel, bluegrass, and country musics. Their duet singing was non pareil throughout their recording career in bluegrass. However, once the right personnel and the right timing had matured into the seasoned interaction between talented individuals, the Jim and Jesse sound was distilled.

The Musicians

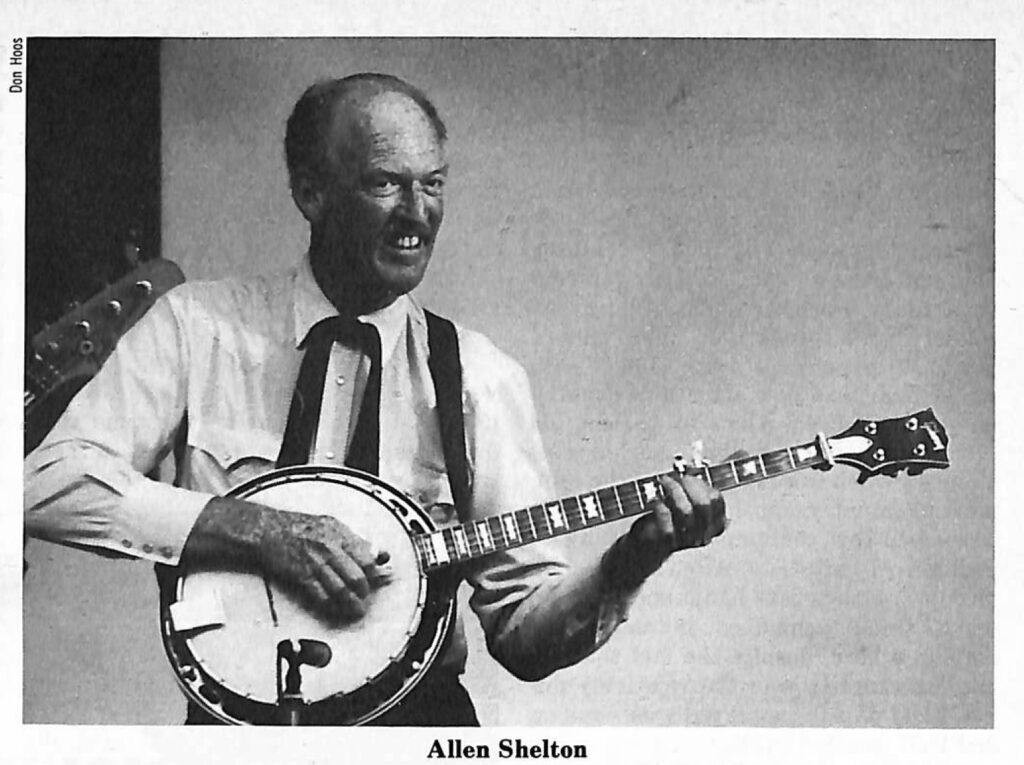

Allen Shelton was born July 2,1936, near Reidsville, North Carolina. His father, Troy Joseph Shelton, was his earliest musical mentor; his mother was not actively musical. Troy Joseph, a singer who played guitar, fiddle, and was learning 5-string banjo, used to play and sing after work and at house parties. Allen at first listened and watched intently, then gradually picked up mandolin (a Kalamazoo f-hole) using chordal techniques and then learned guitar. Bill Monroe and Chet Atkins were his early musical idols.

Allen began to learn 5-string banjo at age 14 when a banjo was needed to accompany an old-time square dance. Allen borrowed one and his father showed him a basic index-finger forward roll, similar to an early style of Don Reno’s. Allen’s most capable early teacher was Hubert Davis, who was working in nearby Danville, Virginia, a devotee of Earl Scruggs’ style.

Allen first performed on WLOE, Leakeville, North Carolina, following in the footsteps of his father. His first professional relationship was with Jim Eanes and the Shenandoah Valley Boys, succeeding Hubert Davis in 1952; he stayed with Eanes for nine months. In the summer of 1953, he was picking with Mac Wiseman, one of the early giants of bluegrass. Allen helped Mac record such Wiseman classics as “Love Letters In The Sand” and “Keep On The Sunny Side” for Dot Records (1191, 1224; re- released on DLP 25896). Because of Mac’s strenuous road schedule, Allen was lured away after 6 months to play with Hack Johnson and the Tennesseans, mostly in and around Raleigh. With Johnson he recorded at WPTF, Raleigh, the bluegrass instrumental “Home Sweet Home” on Colonial Records (CR 701 [F8-0W-0767]), the first such instrumental to achieve enough popularity to be covered (recording of the same arrangement soon after the original release in order to exploit the original’s comercial appeal) by several other artists, the most popular variant being Don Reno’s.

In 1955 Allen was part of a splinter group from the Tennesseans who formed the Farm Hands, led by Curly Howard, a band that stayed on WPTF. When the Farm Hands dissolved in 1956, Allen returned to Jim Eanes and WHEE, Martinsville, West Virginia, with whom he recorded some strikingly clear, confident banjo on his Gibson RB-250. Most remarkable for the banjo presence was the Starday release by Eanes which featured Allen’s break to “Log Cabin In The Lane” (45-456). Also noteworthy were Allen’s own arrangement, “Round Town Gals” (“Buffalo Girls”), his original instrumentals “Dine-e-o” (SEP 130B) and “Bending The Strings” (Starday 45-366-B), the latter to be adopted by Jim and Jesse as their theme instrumental for their live television shows in the early 1960s. In 1958 Jim Eanes and the Shenandoah Valley Boys recorded in Washington, D.C., the outstanding 45 rpm single, “Long Journey Home” backed with Allen’s unique instrumental arrangement of “Lady Of Spain,” on Blue Ridge 510 (45-6011). In the fall of 1960 Allen was invited by Jim McReynolds to join the Virginia Boys.

Allen’s banjo picking has always been very precise, driving, bouncingly syncopated, and consistent. Nearly all of his notes were well balanced in terms of pick pressure; each note seemed to really “belong” as individual notes and within their greater context of patterned rolls, not merely a note in passing or fillers for more predominant melodic notes. His playing can best be characterized as embodying impressive presence. Shelby Singleton is credited with having said that Allen’s banjo work significantly defined the instrumental part of the Jim and Jesse sound. With the recent departure of Mike Scott from the Virginia Boys, Allen has now resumed his former position as banjo picker and continues to shape the sound of the Virginia Boys with his distinctive music.

Jim Buchanan was born January 1, 1941, in North Carolina. His mother taught him basic chords on guitar; later his father taught him fiddle. He began his musical career in 1950 at age 11 with Joe Franklin and the Mimosa Boys, of Morganton, North Carolina, and stayed with them until 1959. His early professional musical idol was fiddler Benny Martin. Jim later worked in the staff band on WCYB, Bristol, Tennessee- Virginia, on shows receivable by radio in Jim and Jesse’s hometown area of Coeburn, Virginia. He worked for Arthur Smith in Charlotte, North Carolina on the radio and on personal appearances from 1960 to 1961. Just prior to his invitation from Jim to join the Virginia Boys, he played drums while Bobby Thompson played bass as sidemen in The Starliters, a four-piece country band in Columbia, South Carolina. When they were not playing in The Starliters they played fiddle and banjo together.

Jim joined the Virginia Boys in early 1961 when he was barely 20. During more than two years of touring with Jim and Jesse, he played in the back of the bus for up to 4 or 5 hours a day. He remembers he would play his fiddle parts and hum the other parts whenever possible. Allen recalls Buchanan played a great deal with Jesse whenever they could find mutual time for trading breaks back and forth.

While with the Virginia Boys, Buchanan became one of the most innovative, bold, decisive, technically precise and crisp solo fiddlers in bluegrass. He also understood his dual musical role of soloist and accompanist, complementing Jim and Jesses own vocal and instrumental performances with subtly dynamic, tasteful backup fills, licks, and full, rich double stops. His aplomb on live shows was commanding. He provided both breadth and depth to the band by presenting considerable visual, as well as musical, interest to the audience. “I never thought of ‘following footsteps,’ only that I believed then and now that ‘I must be me.’ I interpret music as I do all things in this life. There are times to be part of the team and times to ‘solo’; knowing the difference makes the difference.”

Allen offered his opinion of Jim’s value to the Virginia Boys: “In two years, he really got it rollin’, and really perked everybody up. He was fresh, and came up with new material. He improved threefold.”

Jim left the Virginia Boys in March 1964, returning in April 1966 for two more years with Jim & Jesse leaving for a second time in May, 1969. In retrospect, he summarized his musical growth and contributions thusly: “I feel that my playing improved because of the clean J & J style which allowed for playing in the ‘cracks’ properly.” His most important contributions were, in his own words, his “all important rhythm & drive as well as tempo and my true feelings and application of such in my participation in the J & J sound.”

Don McHan, singer, songwriter, and instrumentalist, born July 11, 1933, is a native of Bryson City, North Carolina. His first professional job and radio exposure began in 1951 when he joined Wade Mainer as mandolinist in Winston- Salem, North Carolina. Thereafter he went to Cas Walker’s program on WNOX, Knoxville, Tennessee, where he played 5-string banjo with Jimmy Martin. He joined Carl Sauceman next and remained with him off and on for nearly 3 years picking banjo. His first session work was in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, with Sauceman on Capitol Records, A & Rd by Ken Nelson. His last professional involvement before entering the Army included less than a year with Charlie and Danny Bailey, the Bailey Brothers, at Wheeling, West Virginia, in the latter part of 1952. Don met Jesse while in the Army. As soon as Don was discharged, Jim and Jesse hired him as their banjo player in April 1956. Don was flexible enough to remain with the Virginia Boys as second (backup lead) guitar, harmony and some lead vocals, and playing electric bass when Bobby Thompson became Jim and Jesse’s banjo picker around November 1957. Don remained with Jim and Jesse through the recording of “Bluegrass Classics” in 1963.

The Virginia Boys in the early 1960s can also be heard on a twin-pak paid for and distributed by Jim and Jesse in cooperation with CBS’s Special Products Division which re-pressed the masters of “Bluegrass Special” and “Bluegrass Classics” (rereleased 12642 and 12643, respectively) in June 1973. Without prior consultation or agreements with Jim and Jesse, ten selections from the Columbia- Epic contract were released in the mid-1960s on Columbia’s budget label, Harmony, as “Wildwood Flower,” HS-11399. Regrettably, these albums have been long out of print.

Suggested Reading

Bob Artis. Bluegrass. New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1975, pp. 76-83, 119.

Eddie Birt. “Jim and Jesse McReynolds.” Country & Western Spotlight, n.s., No. 9 (December 1976), pp. 9-11.

“Five Favorites: Jim and Jessie [sic] McReynolds.” Cowboy Songs No. 28 (1953), p. 25.

Scott Hambly. “Jim and Jesse: A Review Essay on Fan Historiography.” John Edwards Memorial Foundation Quarterly No. 46 (summer 1977), pp. 96-99.

Fred Hill. Grass Roots. An Illustrated History of Bluegrass and Mountain Music. Rutland, Vermont: Academy Books, 1980, pp. 58-60.

Scott Hambly liner notes to “The Jim and Jesse Story.” Double-album set, CMH-9022 stereo (1980).

Gary Henderson. “An Interview with Don McHan.” Bluegrass Unlimited, May 1969, pp. 7-8.

David Magram. “Jim & Jesse.” Pickin’, May 1974, pp 4-8.

Bill C. Malone. Country Music, U.S.A. Publications of the American Folklore Society Memoir Series, Volume 54. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1968, pp. 329-339.

Jean S. Osborn. “Jim and Jesse —‘The Virginia Boys’.” Disc Collector No. 17 (May 1961), pp. 16-17. Jean S. Osborn. “Jim & Jesse.” Country Music Fan Fare, Winter (December) 1961, pp. 6-7.

Steven D. Price. Old as the Hills: The Story of Bluegrass Music. New York, The Viking Press, 1975, pp. 67-69.

Mike Rodgers. “Jim and Jesse” A Trip To England.” Bluegrass Unlimited, July 1976, pp. 26-28.

Neil V. Rosenberg. Bluegrass: A History. Urbana and Chicago:University of Illinois Press, 1985, pp. 314-315, 361-362, passim.

Nelson Sears. Jim and Jesse: Appalachia to the Grand Ole Opry. Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1976. Excerpts appeared in “Jim and Jesse: Appalachia to the Grand Ole Opry.” Muleskinner News 7:4 (ca. 10/72), pp. 6-9, 14-15.

Bill and Bonnie Smith. “100,000 Miles away from Home —Jim and Jesse on the Road.” Bluegrass Unlimited, August 1975, pp. 8-18.

Irwin Stambler and Grelun Landon. Encyclopedia of Folk, Country, and Western Music. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1969, pp. 157-158.

Kathy Stanton. ‘‘Jim and Jesse Bluegrass Concert [in Denver].” National Bluegrass News, March-April 1975, p. 5.

Janet Taylor. “The Better Half of Jim and Jesse & Va. Boys.” Bluegrass Unlimited, August 1970, pp. 2-5.

“Virginia’s Own —Jim & Jesse.” Folk and Country Songs No. 19 (December 1959), p. 31.

Jim and Jesse are fortunate to have many loyal and devoted fans in nearly every state of the Union. They are organized under the aegis of the Jim and Jesse Fan Club. Mrs. Jean S. Osborn has been their president for over 25 years. Mrs. Osborn writes several newsletters and one journal annually covering Jim and Jesse’s shows, calendar of future events, family life, fan fair, and participations in the DJ convention. For information, write to: Mrs. Jean S. Osborn, President, Jim and Jesse Fan Club, 404 Shoreline Drive, Tallahassee, Florida.