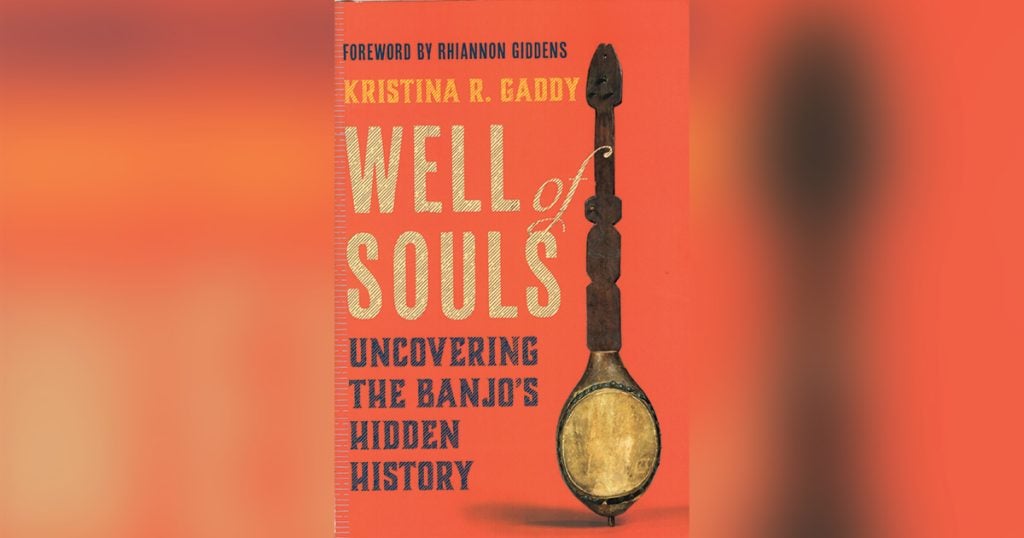

Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History

Kristina Gaddy, a Baltimore-based writer and fiddler, has written exactly the book the banjo world needs right now. She explores questions that many among us, including myself, have been asking since the turbulent summer of 2020, including, “Why was it that an instrument constantly described as ‘Black’ and ‘African’ came to be thought of as a white instrument?”

Well of Souls builds on and expands the most recent published scholarship on the history of the banjo (The Banjo, by Laurent Dubois, and Banjo Roots and Branches, edited by Robert Winans) adding important context, newly discovered evidence, and looking at it all through a wider cultural lens than previous works.

Gaddy makes her own point of view and cultural bias, that of a Swedish American white woman, explicit. She also enumerates the biases of the historical characters who documented early banjos in writing, in drawing, or by collecting them. How much would they have known about the music they were hearing, the dance they were seeing, the culture they were observing?

We do not have first-person accounts from anyone who actually played the earliest banjos. All we have are historical observations of mostly white European men, which have been interpreted in the modern era largely by white historians. How much are we missing? What misinterpretations have we made because of our cultural viewpoints?

Gaddy argues that a big piece we’ve been missing is that “the banjo once served a higher purpose” than the music-making, entertaining secular role it has come to be known for. “The banjo was not just a musical instrument but a spiritual device,” playing a role in religious ceremony for the enslaved and free Black populations in South and North America.

Early evidence of the banjo’s development is rare: fewer than fifteen images prior to 1820 have been discovered. There are only four extant early gourd-bodied, African-American made banjos, with the fourth only recently having been unearthed in a Paris museum in November 2021. In many of the written accounts and artistic renderings the banjo accompanies dance, sometimes along with drums. Despite the fact that drums and dance are widely recognized as having religious significance, we somehow failed to make that connection for the banjo.

Gaddy’s research is thorough and she documents it with extensive footnotes. Her writing is engaging and easy to read. She has also uploaded to her website further historical materials which wouldn’t fit into the book: images, audio clips, musical notation for the songs she references, maps, and a video presentation she and banjo builder Pete Ross gave at a recent conference on “What is an Early Banjo?” She also offers an “Essential Banjo History Reading List” for those who want to broaden their understanding of this topic.

The Coda to the historical part of the book jumps to the present day where Gaddy interviews several Black banjo players—among them Dena Ross Jennings, founder of the Affrolachian On-Time Music Gathering; Hannah Mayree, founder of the Black Banjo Reclamation Project; and Jake Blount, an award-winning, widely-touring old-time musician—who are bringing the tradition into the modern era. She points out that “It’s time we listen, learn, and support them and the many other Black people doing this work.”

With Well of Souls Gaddy hopes that “we’ve uncovered enough now that the banjo won’t be seen as foolish or the butt of a joke, but as an instrument worthy of our attention and study, an instrument that reveals our American history.” If you play the banjo, or play in a band with a banjo, or listen to music that uses the banjo, the information presented here can help connect today’s musical strains to their deep roots that are just beginning to be rediscovered and acknowledged.