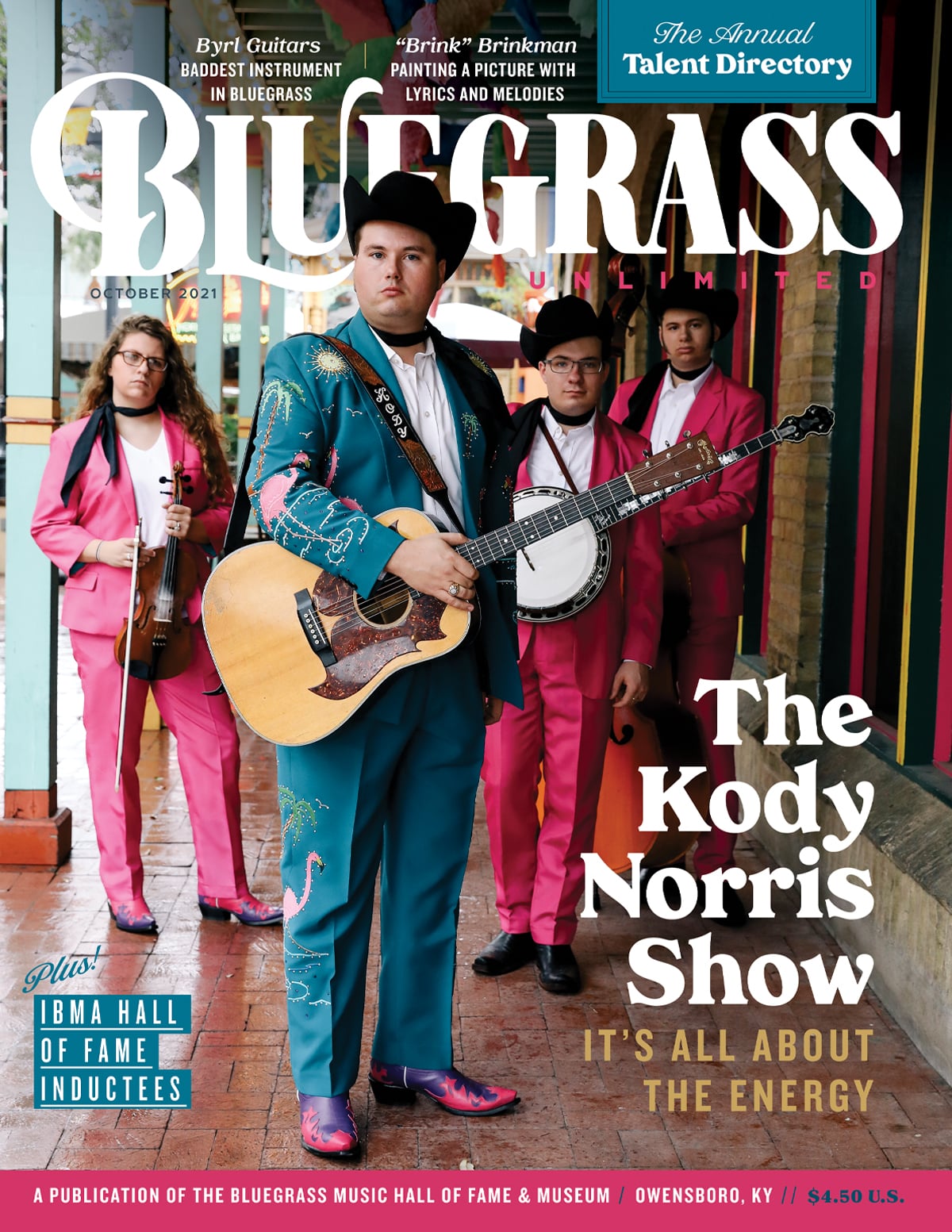

Home > Articles > The Archives > Wayne Yates: Bluegrass Habits…. Hard To Break

Wayne Yates: Bluegrass Habits…. Hard To Break

Republished from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1982, Volume 16, Number 8

“Could it have been three years since we’ve seen him?” Steve Stephenson thought a moment and replied, “Every day of it. We were playing in Stuart, remember?” Sure, it was all falling back in place.

It was Saturday morning, I had gone in search of my friend. Bill Yates, just to talk a little bluegrass and relive a few yesterdays. Upon arriving at the Country Gentlemen’s bus, I saw Bill talking to a tall, distinguished man carrying a mandolin case. Turning to Steve, I asked. “That guy looks awfully familiar…who is he?” Steve answered, “You’ve seen him in Red Allen’s old promo photos…that’s Wayne Yates.” How about that! I thought he had retired from music years ago, and here he was…ambling about a festival park in July.

In essence, my thought was correct as Wayne was not actively pursuing his music in the commercial sense of the word at that time. Yet, today, he is back, going strong, and producing the best music of his career.

Wayne’s parents were originally from Buchanan County, Virginia right in the heart of coal mining country. In fact, his dad began mining at age sixteen, a difficult life at best, but a job with which he had grown up doing. As the Depression grew worse, steady work at the mines was often difficult to find, and lack of work prompted many lay-offs or, worse yet, the closing of those mines operating on borrowed capital. During those times of inactivity, the Yates family would move northward to Fairfax and Prince William counties where farming provided the means by which they would earn a living. It was in the midst of one of these sojourns that Wayne was born in Manassas, on April 9, 1933.

In 1935, the family moved back to the coal mining region, and Wayne’s father returned to work. Wayne vividly recalls the hard times faced by a family of three boys and two girls, all of very early ages. Spendable income was almost non-existent. “My clothes had patches, and the patches had patches,” commented Wayne. Yet a determination to survive bound the family and kept them close.

Saturday evenings found them huddled around an ancient battery powered radio listening to WSM’s Grand Ole Opry, and Wayne remembers to this day the “honest to goodness” country sound of Roy Acuff and “that high lonesome sound” of Bill Monroe. The radio was not the only form of entertainment around the Yates household; “We always had an old guitar around the place and we’d have family singing all the time. Dad picked the guitar and sang…everybody would join in and we could entertain ourselves for hours like that.”

Wayne’s initial introduction to formal music came in 1941. His father had scraped together enough to carry the family to a live country music show in Richlands, Virginia. “That was the first time I remember seeing a bluegrass band…’course, they didn’t call it bluegrass back then.” Nevertheless, it was Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys, live, in person. The thrill could not have been any greater nor the memory any more vivid had it been President Roosevelt himself. “I was fascinated by the picking…yet it was the singing that really got to me. Yes, more especially, the singing.” There could be no doubt from this point on; the seed of music had been sown.

1942 found Wayne moving, with his parents, back to Prince William County. Work in the mines had become unbearable for the elder Mr. Yates, and the offer of steady employment as foreman of a large farm couldn’t be overlooked. Everyone in the family was soon working on the farm, and, even though times improved somewhat economically, music didn’t cease to be a great part of their lives. “We carried on our tradition of home entertainment. We would all sit around and pick and sing. That has been a part of my life as long as I can remember.”

A few months had passed and music took another direction for Wayne. “Dad went to town one day and came home with an odd looking case under his arm.” The new arrival was a mandolin, brand new from Sears-Roebuck. After his father tuned this treasure, “he showed me a little bit about it…mostly tunes on open strings. Later, I learned a few chords.”

“We were attending a Pentecostal church at that time, which always had string music.” Soon, Wayne, his father, and uncle were performing regularly as a trio: Wayne, mandolin; Mr. Yates, guitar; and his uncle, accordian. Wayne remembers those early days, “I’d have to watch them to see what chord they’d play in, then kinda figure it out myself. I learned a lot though and it was fun doing it.”

In high school, a small band featured at Saturday dances in Manassas provided Wayne with another outlet to play organized music. “There was nothing to do in those days but go to the movies and stand on the street corners,” recalls Wayne. “I think the police department felt better with all of us corralled in one place, so they sponsored the dance.” It was another terrific learning experience not only for the “silver fox” of bluegrass music, but also others in that band. “We all learned to enjoy music, and several of us had pursued it later in life.”

The Korean War suddenly hit the country by storm affecting the lives of many young people and their families. The Yates family was no exception. Both Wayne and Bill answered the call to arms, and music, to Wayne, became secondary. Nevertheless, his old guitar accompanied him throughout those Air Force years, and, though Wayne never played organized music while in service, he could not refuse a good jam session. “We would often sit around the barracks and pick and sing. Being away from home, the music made you feel a little closer to those you’d left behind.”

Wayne and Bill returned home in early 1956 and began taking what they learned as children about music and putting it to work. With older brother, Jim, they began informally working up a trio. It was “nothing serious, you know, just for our own amusement. In fact, Jim never did get into it quite as much as Bill and myself.”

All of this couldn’t have happened at a more precise time. It was during this period that bluegrass music began to flourish in the metropolitan Washington area. The Country Gentlemen were just getting started in a little club near Bailey’s Crossroads; in addition, Benny and Vallie Cain, Buzz Busby, and the Stoneman Family were all working the area on a regular basis. As Wayne recalls, “That’s nothing in comparison to the bands working Washington today. Just the same, every time Bill and I could find a place where they were having bluegrass music, we would be there. I guess that gave us the inspiration to keep going.”

In 1959, Wayne got the opportunity to join a band, organized by Bill Bailey, playing mandolin, and they found a regular gig in the Club Hi-Fi just outside Baltimore. As Wayne described it, “Club Hi-Fi was a long way from some of our more uptown clubs of today, but it was a place to pick. In addition, our shows were broadcast on local radio.” He continues, “it wasn’t the money, but the exposure” that kept them together. This group, though never formally adopting a name, thrived for a short while, and Wayne recalls those years, “it taught us how to present our music to an audience. We would play every place we could, regardless of whether there was money involved or not. Money was not the first thing we were concerned with, we just enjoyed playing music.”

Although brother Bill never joined this group, he and Wayne continued to work on their music informally. Consequently, in 1960, they joined forces and formed a band called The Yates Brothers and the Clinch Mountain Ramblers. In addition to Bill and Wayne, none other than Bill Emerson played banjo and Ferrell Brown (who later became their brother-in-law) played guitar. Ed Matherly, a disc-jockey at WKCW, Warrenton, “took a liking to us” and put the band on radio. Ed had other connections which also proved helpful to the Ramblers and their efforts to make a name for themselves.

Because of his affiliation with the radio station, Ed had access to advance notice of pending road shows passing through the Northern Virginia area. He worked diligently to get the brothers booked as a front band for such bands as Flatt and Scruggs, Jimmy Martin, the Osborne Brothers, and, of course, Bill Monroe. Wayne doesn’t try to deny the fact that Ed Matherly probably had an ulterior motive in hyping his radio show but adds, “we got quite a bit of recognition being on the same show with those name bands.” This also opened up other club opportunities for them and soon, Wayne and Bill found themselves playing as many as five or six nights a week.

As so often happens when a band becomes better known, attrition became a problem. Jimmy Martin, who at this time was a regular on WWVA’s Jamboree, beckoned Bill Emerson to replace J.D. Crowe. Ferrell Brown seized this opportunity to leave; he departed for personal reasons. However, this was not the end. Wayne and Bill soon found replacements in the persons of Smiley Hobbs on banjo and Bill Harrell, guitar and lead vocal. Buck Ryan, having become dissatisfied with the Texas Wildcats, joined, and the fiddle brought a new dimension to their band. The new band was working as much, or more than, the previous edition, “Of course, we were young and eager. We would show up any place that needed a band.”

Only one recording, a single, came out of this endeavor. That was for the Kash label in 1962. The revised Yates Brothers and the Clinch Mountain Ramblers recorded “Please Keep Remembering” —written by Bill Harrell and “(Take) Love’s Chance Again” —by Lola Emerson. Wayne feels as if this band was really rolling at this point, but, just the same, it was to be short-lived.

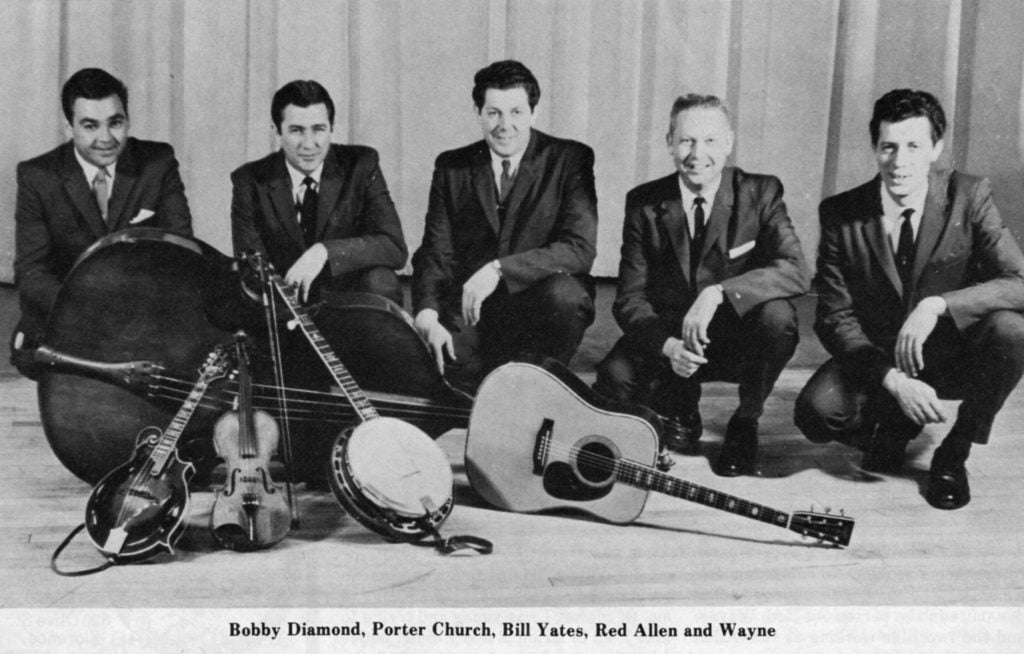

1963 brought with it more personnel changes. Bill Harrell and Buck Ryan gave notice at about the same time, and, soon after, Smiley Hobbs sought work elsewhere. Nevertheless, as is often the case, misfortune can reverse itself into a blessing. Who should appear on the Washington bluegrass scene looking for a band but Red Allen, and who should return home looking for work but Bill Emerson. The combination proved to be dynamite in the persons of Red, Wayne, and the two Bills working as Red Allen and the Kentuckians.

The Shamrock (truly a bluegrass shrine to those of us who remember) at 33rd and M Streets in Georgetown (D.C.) soon became home base, and the Kentuckians quickly began to carve a notch in the bluegrass family tree. Their schedule was grueling, club dates, often as far away as Rhode Island, Saturday nights as regulars on the (WWVA) Jamboree in Wheeling, and numerous guest appearances on the Old Dominion Barndance in Richmond, Virginia.

This band recorded its first album in 1965 for the Melodeon Label. It was entitled “The Solid Bluegrass Sound by The Kentuckians” and featured Chubby Wise playing fiddle. Wayne fondly remembers this effort, “I don’t even know if it’s available today. In fact, I don’t even have one. I’d like to get hold of one to just see what we sounded like.” The Kentuckians found themselves in the studio a few months later to record an album for County. This one was destined to become a classic from the beginning. In addition to Red, Wayne and Bill Yates (Bill Emerson had departed shortly after the completion of the first album), it featured Porter Church on banjo and Richard Greene holding up the fiddle chores. “Bluegrass Country” (County 704) “pleased me a great deal” commented Wayne. “I thought we had a pretty good sound as well as material.”

Not long after the second album was released, the schedule began to overwhelm Wayne. “It was rough and I mean rough! I didn’t know what it was doing to me. Of course, I was young and trying to take it all in stride. I really didn’t notice what it was doing to my body.” So, Wayne got brother Bill and Red together, broke the news to them, and set out to face life without music. They knew, commented Wayne, that “I hated to call it quits…music was a part of me.” But the dye was cast. “I just had to lay it down for a little while.”

That little while lasted for three years until Bill Emerson returned home from his second tour with Jimmy Martin. “We started playing a little music with a guitar player named Cliff Waldron.” Numerous club dates and local package deals followed over the next few years, but, once again, Wayne felt those old road weary blues creeping into his head. In 1972, Wayne laid music aside for almost seven years. (Bill Emerson and Cliff Waldron went on to form the Lee Highway Boys, later changed to the New Shades of Grass, make a lasting impression on bluegrass music—but that’s another story in itself.)

During this period, many people urged Wayne to return to his first love. “They made me feel guilty. I guess I probably told more lies about not picking than I told the truth.” Nevertheless, the fans kept pushing including, “my number one fan, my wife. Nova, and I kept promising to return when the time was right. That day finally dawned in 1979 with Jimmy Arnold’s return to Northern Virginia.

Wayne explains his return: “Arnold (Arnold Hobbs, owner, Partners II, Centreville, Virginia) wanted to feature bluegrass music on Thursday nights. So Jimmy and I decided to put something together.” This time, Wayne was playing guitar and singing lead in a group simply called Yates, Arnold, and Company. “Things went on for some time with various musicians…Dave Auldridge, Ed Wilson, Ed Stepanion, Donnie Bryant, and Billy Wheeler, just to name a few. When you came up to hear us on Thursday nights, you never knew who would be on stage. I guess we had everybody up there but Bill Monroe…usually at one time.”

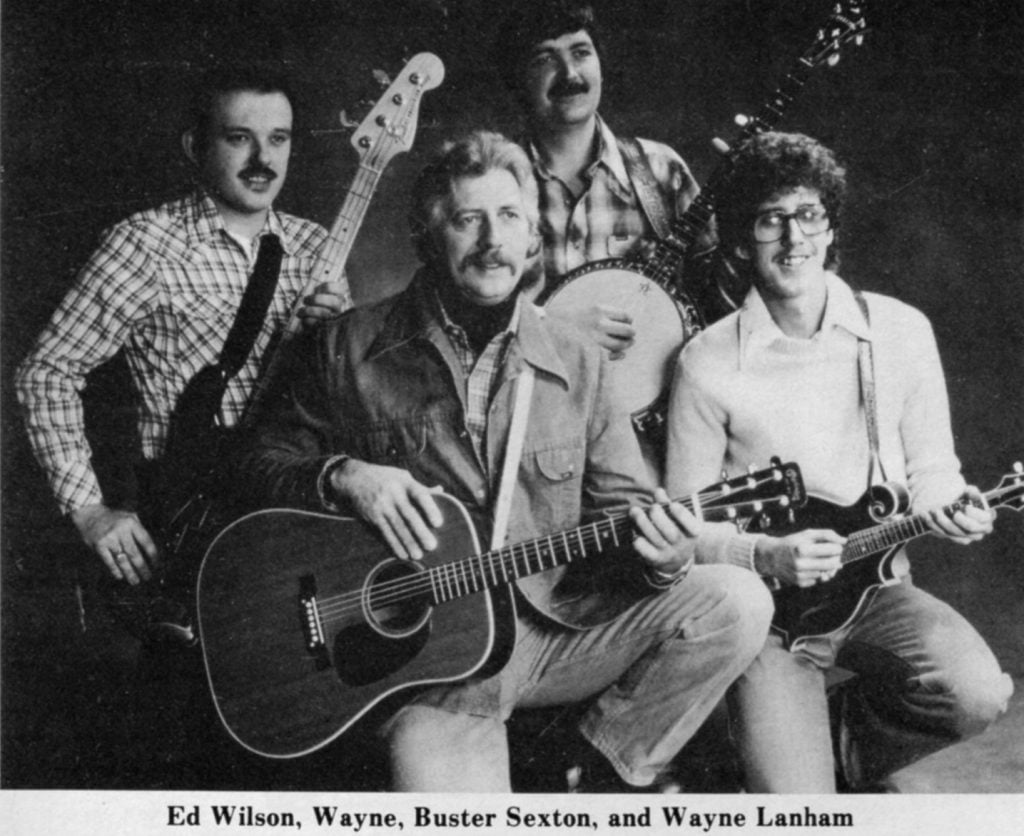

Jimmy returned to his native Greensboro, North Carolina in the spring of 1980, and Wayne decided the time had come for him to make his move. Consequently, Wayne Yates and Company was born. Joining Wayne in this endeavor was Ed Wilson, a veteran bassist on the D.C. music scene, and an accomplished baritone vocalist, Everett ‘Buster’ Sexton, an old friend of Wayne’s, playing banjo, and Wayne Lanham, who at only twenty-one years of age picks super mandolin, adding tenor vocal.

Yates and Company is, without doubt, Wayne’s pride and joy. “I want to take music and do it in my style, then have people recognize that. It’s important to me that my first individual band effort make some contribution to bluegrass music. I don’t want to make a million dollars…just be able to perform the music as I interpret it, the public’s going to let me know if it’s right or not.”

Their album “Relivin’ Old Habits” (Outlet STLP 1029) is the Company’s first effort to make this contribution, and features Jimmy Arnold on fiddle. Although the album has only been released a short time, it’s already receiving airplay in the major bluegrass markets and features a variety of trios, duets, gospel quartets, as well as instrumentals. “I think you’ll find a Jimmy Martin influence there,” says Wayne, “it’s got that drive.”

Wayne, in addition, knows the importance of showmanship in music. “I like to entertain people not only with my singing but also with a joke or two. As long as I’m on stage, I’m at home. It’s that combination of being an entertainer as well as a musician that’s helped sell my music over the years. You know, I don’t consider myself a super picker.” Naturally, that’s a matter of opinion, but having sat through one of their club dates, this writer found it to be a most entertaining evening, not only the music but also the sore sides from laughing. The man’s a genius at holding you in the palm of his hand…quick one liners, then..boom!, you’re in the midst of a hard driving bluegrass song.

Although Wayne Yates is looking forward to the future, his attitude is tempered by the past, and he never fails to caution novices of trials on the road. “In order to play good music, your mind must be clear. If you mess with drugs or alcohol, your mind doesn’t work clearly: you can’t do your best job. You’ve got to keep yourself straight and do your homework. Learn those basics first, Flatt and Scruggs —Jimmy Martin, the rest will follow.” As you look in his eyes, you can tell Wayne speaks from experience and a certain strength gained from it.

Wayne Yates is back. Is he ever! His music proves it. Perhaps I was wrong to ever think he had retired; musicians never retire, do they? No, I believe Wayne simply took a few years to refine and polish his music. Now, he’s taking it to the people. “It’s the people you’re working for. Some musicians seem to forget that. It’s their approval or disapproval that can make or break you, and, when you loose sight of that, it’s time to quit.”

If it’s the people that will keep you in bluegrass music, Wayne Yates and Company will be around a long time.