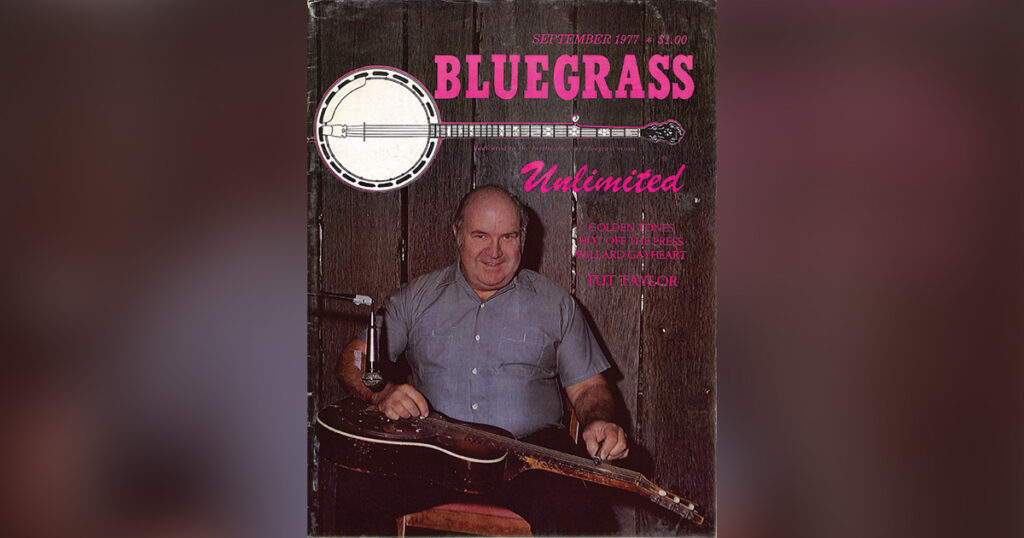

Home > Articles > The Archives > Tut Taylor—Bluegrass Enigma

Tut Taylor—Bluegrass Enigma

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 1977, Volume 12, Number 3

Entrepreneur, musician, festival lover and hater, sign painter, instrument builder, collector, author of pointed letters and want ads to BU, Tut Taylor’s wildly varied career is one of bluegrass music’s most fascinating enigmas. His interests and activities are so scattered [and yet usually simultaneous] it is difficult-in fact, well nigh impossible- to give him a label or fit him into a convenient category.

Musically it is the same story – an arch traditionalist, ardent Bill Monroe devotee, the man who lost money year after year renting an entire floor of a downtown Nashville hotel so bluegrass musicians could jam during the frenetic disc jockey convention. That’s him, yet it’s the same man who is enthusiastic about the New Grass Revival and John Hartford, and Neil Young, for that matter; and who plays the Dobro with—of all things—a flat pick. An enigma.

Robert Taylor was born in Milledgeville, the sleepy little ex-capitol of the now fashionable state of Georgia, on November 20, 1923. “We were a musical family. Very country, very backwoods, really full Georgia people. Back then times were pretty hard, and about the only thing we got out of life was music.” They were a musical family as well, and Tut began playing the banjo, emulating his father, at about ten years old, but moved on to the mandolin.

It was as a teenager, however, that he first heard the sound of a Dobro over the Grand Ole Opry: “I heard Oswald play one—this was in 1938 or ’39—and when I heard it, man, it tore me for a flip. I didn’t know what the instrument was, so I wrote Roy Acuff and asked him. Mildred (Acuffs wife) wrote me a very nice postcard saying it was a Dobro. So I immediately got one, an original Dobro.”

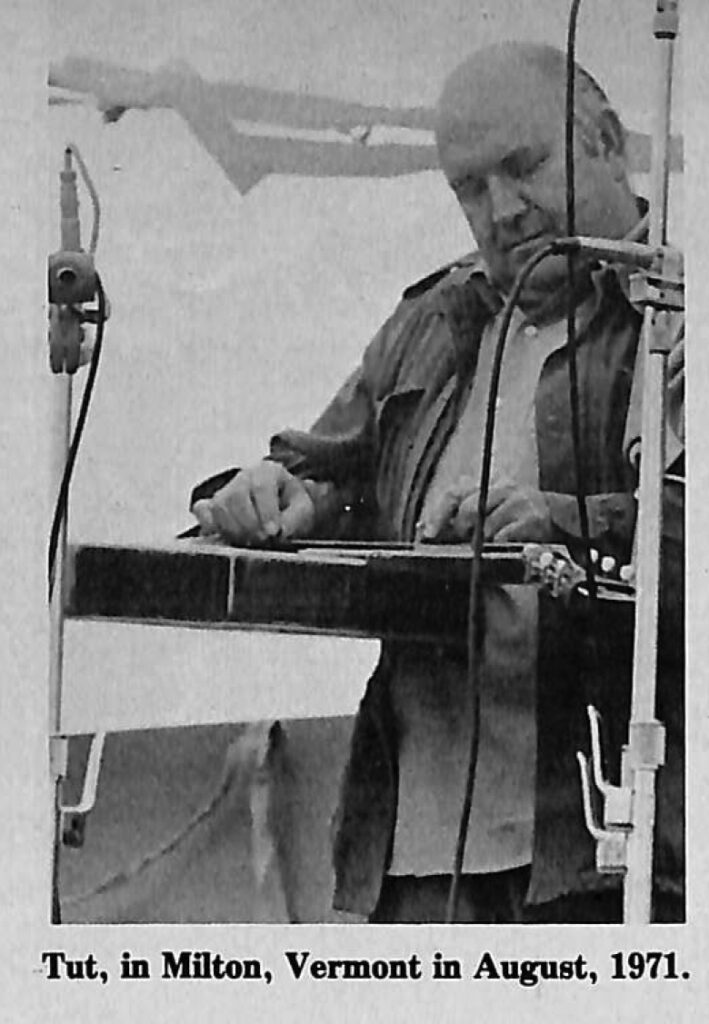

It was there and then that the unusual Taylor flat-picking style was born, more out of rural isolation and naivete than musical innovation: “I didn’t know how the Dobro was supposed to be played, and since I was playing mandolin with a flat pick I just started playing Dobro that way too, not knowing any better. And of course as I learned the instrument I improved, as any guy would.

“I met Earl Scruggs about 1945, and he gave me a set of fingerpicks and said ‘Boy, throw that flatpick away. Take these and learn to play that thing.’ I’ve still got those fingerpicks. I put them on one time and regretted it: they really hurt my fingers! I couldn’t even pick two strings. So I didn’t play with fingerpicks no more.” Despite his intense desire to play music, however, Tut let it remain basically a hobby while he pursued his main livelihood—sign painting and raising a family which would eventually come to eight children. Sign painting is a trade at which he excels—the huge murals which grace the wall’s at the Old Time Pickin’ Parlor in Nashville are a good sample of his work—and it is a trade to which he has periodically returned.

He also turned to another instrument during this period, the electric steel (nonpedal, of course), attracted by its warm, lush tone. He is proud of a recent acquisition, in fact—a Gibson three-neck steel from the 1940s—but he has yet to record with it.

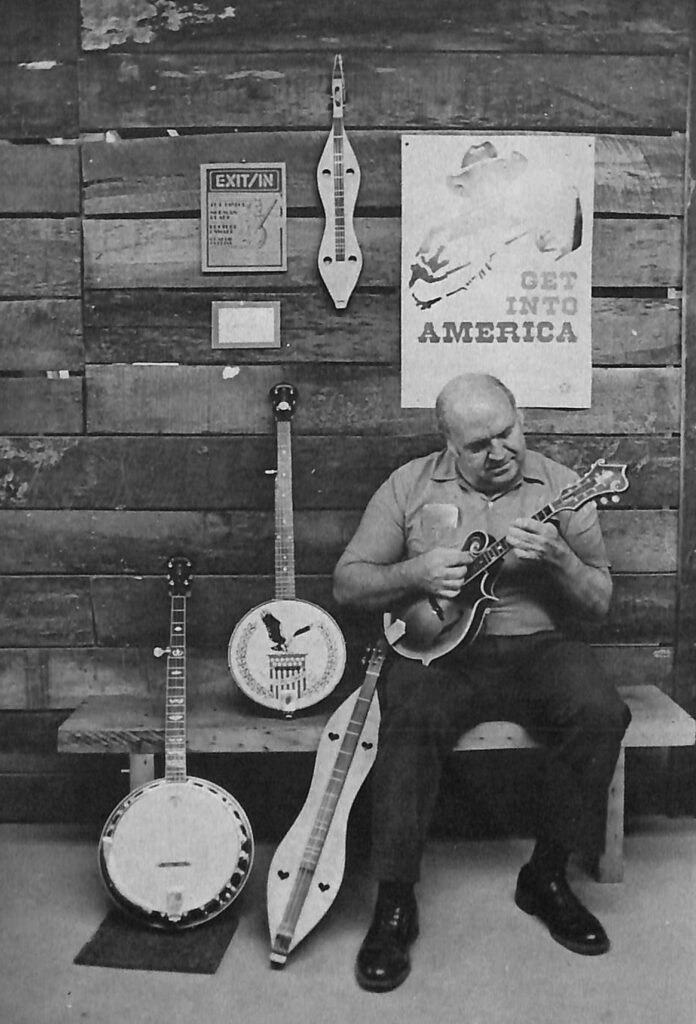

He also became quite well known as a collector and trader during the 1950s, one of the first to recognize the value of original old banjos, mandolins, and guitars. The pride of his collection is, however, a Gibson A-5 mandolin built by Lloyd Loar, apparently the only A model he constructed in his three years with Gibson. It is the model on which all A-bodied/long necked mandolin conversions have been based since. Still, his greatest love was Dobros, and he had at one point a collection of some sixty-one original models. In fact, one of his early albums has a picture on the back cover of a few dozen of them lined up and hung on a barn side, easily one of the more blinding photographs in existence.

With the folk boom of the early 1960s, Tut began to get into some limited recording, doing a couple of oddish albums for World Pacific (one featuring one of the ultimate bizarre instruments, the twelve string Dobro), although he remained a sign painter in his native Milledgeville, collecting and playing on the side.

Finally, however, with a few children grown and the bluegrass boom picking up considerable momentum, he decided to move his family and his huge collection to Nashville, where he, George Gruhn, and Randy Wood formed the original GTR, now known as Gruhn Guitars.

This was nearly a decade ago, and Tut’s career has been scattershot, exciting, and varied beyond comprehension ever since. The partnership with George didn’t last long—he sold out his interest after a year or so—and he returned to sign painting in Nashville, although he also found several months to tour with John Hartford, recording the “Aereo-Plain” album with him for Warner Brothers.

This led to his long association with Norman Blake, the guitarist in that band, with whom Tut has played, toured, recorded and even managed and booked for a considerable period of time.

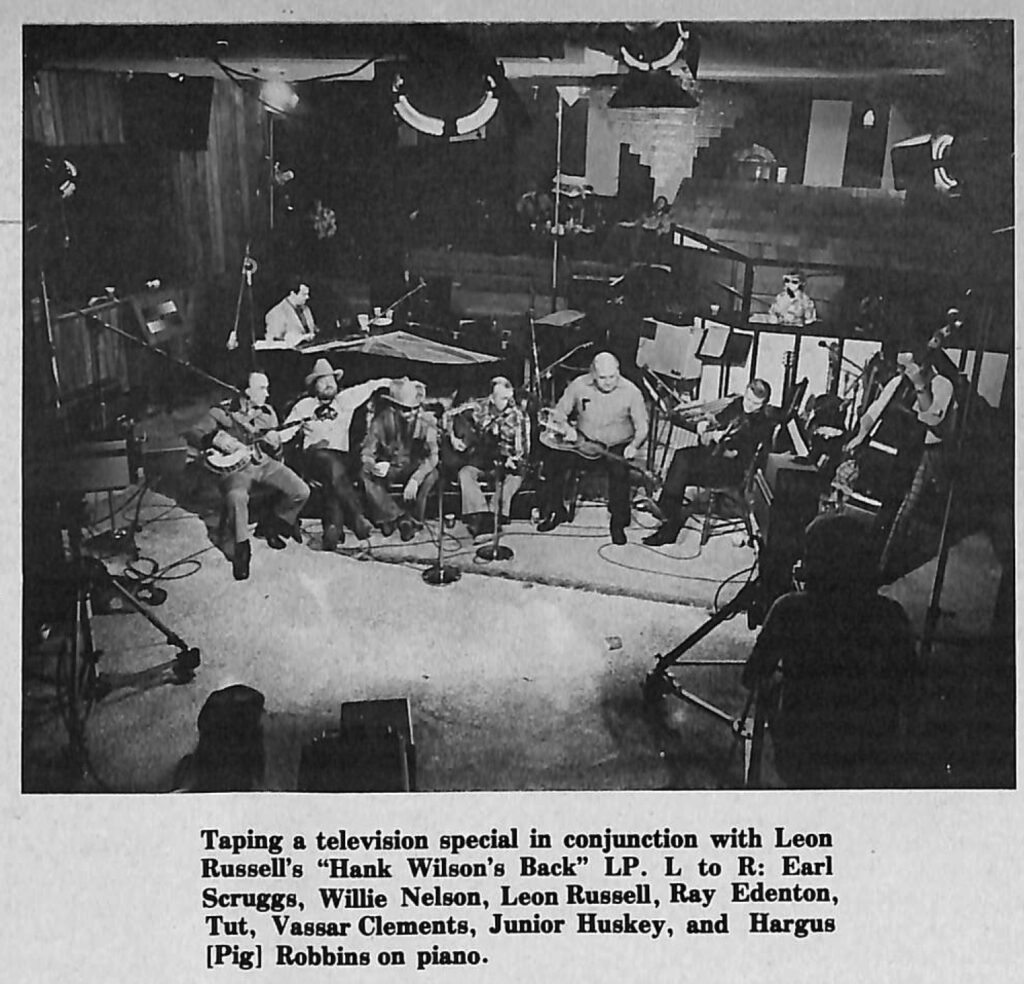

This period also saw Tut, whose unique style had been vastly under-recorded for years, appear on a rapid succession of albums, some with Blake, some by himself, and on a TV special with such well known figures as Leon Russell when Leon was doing his “Hank Wilson’s Back” album. The labels varied as well: from majors like Warner Brothers and Shelter to bluegrass/old-time specialty labels like Rounder, to a couple of Tut’s own: Tennessee and King Tut Records. Mandolin, Dobro, dulcimer; he played them all on at least a dozen albums recorded within a five year span.

Yet his fertile, teeming mind came up with other schemes as well: when Opryland opened it featured an instrument craftsman’s shop at which the strolling tourist could buy a dulcimer purportedly built right on the premises. It was masterminded and operated by—you guessed it—Tut Taylor. When Gretsch wanted to get into the acoustic bluegrass instrument market with well-built mandolins and banjos. Tut Taylor was there. When Grammer Guitars folded and their Arlington Avenue factory was put on the market, it was Tut Taylor who took it over, turning it into a combination general store and handcrafted instrument factory. When Opryland began selling their plickett (miniature dulcimer) and Hee-Haw began selling their Hee-Haw Plank (a not dissimilar miniature dulcimer) it was Tut Taylor who supplied them. When the call went out for Bicentennial banjos, it was Tut who patriotically responded with a red-white-and-blue five string which sold for under $100.

Tut’s still full of ideas, but he seems just a bit more settled than at any time in the past few years. He’s reorganized his business, a family operation which includes his wife and sons Mark and Robert—”We’re a laid back company”—and has concentrated on his line of banjos (top tension, flat head, and raised head) and mandolins, a line of quality instruments of which he is justifiably proud, but which accounts for less then half of his business, the other half being the production of the plicketts, twangers, and Hee Haw Planks, which he sells to Opryland, Disneyland, and other such attractions.

He still does a bit of collecting (“I’ll settle for anything that’s old!”), hasn’t done much playing (“Just enjoying myself in the front of the shop”) and is dreaming up new schemes as well, including a cassette/booklet Dobro instruction course and a new electric solid body guitar: “Nobody makes an electric guitar with the same care and craftsmanship that they do a bluegrass mandolin or banjo; we’re going to be the first to make a super quality electric guitar. Of course we have no plans to abandon bluegrass music or bluegrass instruments.”

Yet the changing factors in bluegrass music and bluegrass instruments are concerns which are very much on Tut’s mind. Of the music, he says “There has been a change, a great change. Festivals, for example, don’t have the same atmosphere, the real thrill and love of the music. Everything seems so much more mechanical, the music and the way it’s played. It seems like everyone is trying to play more notes, different notes, and not feeling the music. It might be because I’m getting older, but I don’t think so. I still love the music as well as I ever did.”

And on bluegrass instruments: “I have a lot of reservations about the future of bluegrass instruments; in a way, it all depends on the Japanese. See, the theory is that the popularity of bluegrass is good for makers of quality instruments, because the new players will probably start on a Japanese instrument, and then—and this is the theory—he’ll move on to a more desirable instrument, either a good quality new one like we build, or a fine old Gibson or Martin or Dobro or whatever. But I’m not sure that theory holds water, because the new wave of pickers just seem to me to be a lot less knowledgable about instruments altogether. They might see no reason to go to a better sounding instrument, because they have no real idea how much better it really sounds-they don’t have a knowledge of what really good tone is. This is something that has really changed since the early days of bluegrass, where every player spent a lot of time thinking about tone and how good his instrument was and how good it sounded.”

Opinionated, irascible, charming, complex, Tut Taylor is an enigmatic bluegrass jack of all trades. As a man and as a musician he is one of the most colorful and distinctive—even unique-members of a unique American subculture, the community of bluegrass.