Tradition & Innovation

Covering All—Or at Least Some Of—the Basses

Once upon a time the A. P. Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers were revolutionaries. A traditionalist scholar once complained that—by introducing guitar into songs that had been previously sung unaccompanied—the Carters just ruined them. Jimmie Rodgers featured jazz players and Hawaiian musicians on some of his recordings, and on occasion he even played the ukulele himself.

Today, their first recordings in 1927 are viewed as central to the founding “Big Bang of Country Music” that presaged today’s multi-billion dollar country music industry.

Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs grew up in a world of the great old-time string bands, of cornshuckings, and of weekend dances led by traditional fiddlers. Yet Monroe and Scruggs were revolutionaries. They got sounds out of their instruments that no one had ever heard before. Now, those of us who see their music as the gold standard, are viewed as hyper-traditionalists.

A hard-core fan once complained to Charlie Waller, a founder of the Country Gentlemen, that Sam Bush and the Newgrass Revival were too progressive to be allowed at bluegrass festivals. “We don’t want that kind of modern stuff,” the fan loudly proclaimed. “We want real bluegrass, like what the Country Gentlemen play!”

“You know,” Charlie smiled, “that’s what the folks who grew up on Bill Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs used to say about us—that the Country Gentlemen were too modern.”

Like it or not, change happens. Winston Churchill summed up the tradition/innovation situation that bluegrass—along with every other art form—has long wrestled with. He said: Without tradition, art is a flock of sheep without a shepherd. Without innovation, it is a corpse.

The Bass Player

Being a bass player takes a special kind of personality. Most of the time, as long as you play perfectly, hardly anyone pays attention to you. But just make one mistake, and everyone looks daggers at you. Spoken or unspoken the message is “What’s going on? You’re making us (or me) sound bad!”

And, of course, depending on how your bass is set up, you may experience hand cramps, troublesome callouses, or even bruised or bloody hands, as well as the hassle of wrangling a gigantic heavy instrument in and out of various cramped spaces. However, one relatively new alternative has begun showing up at jam sessions, and even among professional bass players.

Gracie Meador

Watchers of YouTube videos by the newly-formed Tennessee Bluegrass Band will notice a couple of unusual features on the group’s lovely rendition of “High On a Hilltop.” The clip showcases excellent singing by guitarist John Meador, mandolin player Tim Laughlin and bassist Gracie Meador, backed by fiddler extraordinaire Aynsley Porchak and stunning banjo player Lincoln Hensley. On this video, however, Lincoln is playing an ornate guitjo—a guitar body with a banjo neck. Another surprise is Gracie Meador playing an instrument which is not often seen in the hands of professional bluegrass players: the bass ukulele or U-bass.

“For comfort and playability, I love the Kala U-bass,” declares Gracie. “I’m a petite person, and it’s much easier to note with my small hands. There are certain runs I like that are hard to do on a standup bass. And of course, the U-bass is a lot easier to transport, even though it does require using a bass amplifier—in my case, a Gallien-Krueger. But since our band is aiming at a traditional bluegrass audience we decided to go with a standard upright bass most of the time, which is why I play one on our other videos. If the traditional bluegrass audience comes to accept the U-bass, I’ll be very happy to go back to it.”

Kadence Williamson

Another Kala U-bass enthusiast, Kadence plays for Williamson Branch. Her group’s website provides the following overview: “When she was 10 years-old, Kadence went shopping for a bass at a trade show. She purchased a U-bass, and it has been her constant companion since then.

“Kadence’s playing on her band’s Pinecastle Records single ‘Free’ is believed to be the first bluegrass chart record to feature U-bass. Her performance on the song ‘Blue Moon Over Texas’ helped propel the recording to the #1 spot on the Roots Music Report’s Bluegrass Chart—a position it held for 7 weeks in 2020.”

Back in March 2016 David Morris wrote in Bluegrass Today, “Kadence’s performance . . . sent me to dust off my U-bass to see if it will help my aging hands recover from repetitive strain injuries that make the upright bass too painful to play for any length of time. There aren’t many bluegrassers playing a uke bass, but after hearing what Kadence does here, don’t be surprised if others head in that direction.”

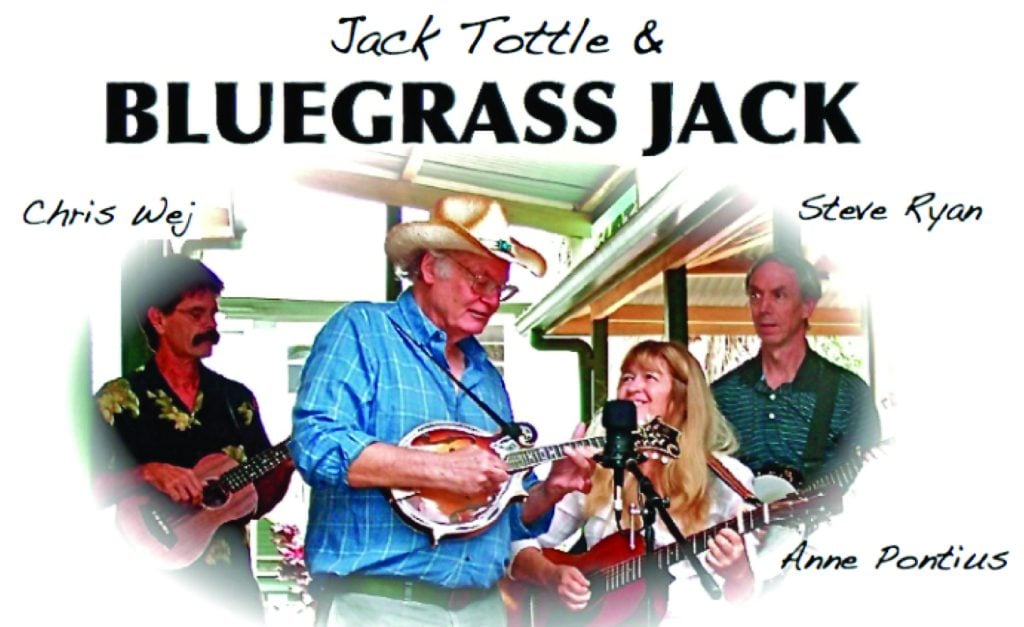

Chris Wej

Around 2010 my North Kohala neighbor, Chris Wej, began playing bass with Bluegrass Jack, currently one of the few serious long-lived bluegrass bands on the Big Island of Hawaii. Though his musical background at the time was limited to garage band rock and roll as a teenager in the 1960s, Chris became fascinated with Mark Schatz’s recorded bluegrass bass work, and with Mark’s instructional video.

Initially Chris tried using a solid body electric bass—perhaps the same model Don McHan played with Jim and Jesse as early as 1959. Chris however, wanted a more acoustic sound. Unfortunately, he was unable to find a standup bass that he felt comfortable with, especially for some of the group’s more adventuresome forays beyond familiar standard chord progressions.

Bluegrass Jack’s guitar player, Anne Pontius, suggested something she’d seen played by a beloved local amateur musician named Kim Sweeney. Prior to retirement, Kim had worked for Canada-France as an Optics Draftsman and later for the W.M. Keck Observatory as an Adaptive Optics Technician. (Both organizations operate large telescopes at the summit of the Big Island’s Mauna Kea volcano.)

Though his instrument was the size of a standard baritone ukulele, Anne said Kim called his instrument a bass ukulele. Chris thought Anne was making a joke. How could a little instrument with such a short neck possibly play the low register of a bass?

Then, a week later, Chris saw a televised live concertfeaturing Paul Simon (of Simon and Garfunkel fame) playing for an audience of thousands. And right behind Paul Simon stood a gentleman named Bakithi Kumalo playing an ukulele-sized bass! Chris realized that—despite its small dimensions—it was something real, and definitely not a toy! “I visited the nearest music store, Collier Thelen’s Music Exchange, twenty miles away in Waimea,” recalls Chris, “and found they had what they called a Kala U-bass in stock. It seemed to be well made, good bracing, inexpensive but decent-looking veneer. I bought one, plugged it into my guitar amp and—nothing! I was so mad. I was sure I’d been taken. I sat there for about 20 minutes and almost threw it in the trash. Then I checked and found it needed a bass amp. When I got the right amp it worked great!

“I bought a Fender Rumble amp with a 15-inch speaker, 75 watts—same energy requirements as a light bulb. I normally don’t need to turn it up louder than ‘1’ on the dial that goes up to ‘10.’ For clubs, coffee houses, etc., it’s more than adequate. For larger outdoor venues, it will, of course, plug into high-powered sound systems as well. For home use I have another Fender Rumble 15 watt amp with 12-inch speaker and face it to the wall.

“It’s not for everyone,” Chris continues. “A few people have said it ‘looks stupid.’ Some audience members have been mystified, saying ‘We’re seeing four people standing there and we can’t figure out where that big sound is coming from!’ Most folks just accept it and enjoy the music.”

Part of the secret to the sound is in the strings. Both Gracie Meador and Chris Wej have experimented with different kinds, and both currently are using the black neoprene rubber strings supplied by Kala. At first these may seem floppy and hard to control, but after acclimating they seem to be ideal for getting as close as possible to the hollow woody sound of the standup bass. With such a short scale, true intonation up the neck does require care in not pushing the rubber strings even slightly sideways. However, as Chris observes, the bass register is forgiving.

Some might be concerned that an inexpensive bass like Kala would be prone to warping especially in an alternately humid and dry, sunshiny and wet, environment like that of the Big Island’s North Kohala district. Windows are open all year, and there’s no need for central heating or air conditioning. “I’ve left my U-bass out of its case for months,” says Chris. “One day I have clouds literally drifting through my cabin on the mountainside here. Next day the sun will be out and the dampness disappears. Then we may get a downpour. Through it all the U-bass has remained solid and warp-free as a rock!”

Close to the time Chris discovered the U-bass, but unbeknownst to him, a video dated October 3, 2011 appeared on YouTube. It was titled “Kala U-bass for Bluegrass.” The subheading was “George Thomas playing U-bass with Code Blue Bluegrass Band.” Standing casually in someone’s driveway, the band delivers a solid, relaxed and enjoyable performance of “Don’t Say Goodbye If You Love Me.” The U-bass fulfills its job just as effectively as each of the other instruments. The site claims over 135,000 views and there are over a hundred comments, virtually all complimentary. Some folks say they have bought—or are about to buy—a U-bass just from seeing the video. A few warn that bluegrass purists will complain. However, Code Blue’s fans have no complaints.

Hawaiian Connections

The original ukulele, of course, owes its popularity to the Kingdom of Hawaii. Immigrants from the Portuguese islands of Madeira and Cape Verde brought the ukulele’s small guitar-like forebears to Hawaii in the 1800s. The ukulele emerged as an important instrument during the reign (1874-1891) of King Kalākaua, the genial “Merrie Monarch” who championed both the ukulele and the hula as valuable emblems of Hawaiian culture, both at home and abroad.

There are some of us who like to tell ourselves that we Americans invented nearly everything of importance. Let us, however, humbly acknowledge that the concepts on which our beloved bluegrass instruments are based (no pun intended) have been brought to us from across the oceans. Our brilliant forefathers (and foremothers?) modified them—sometimes radically, sometimes subtly, into the lovingly crafted instruments we cherish—or covet—today. That history is highlighted in the song “The Bluegrass Sound,” recorded with Tony Rice, Stuart Duncan, Jerry Douglas, Ron Block, Mark Schatz, Pat Enright and myself on the Copper Creek album of the same name:

Well the banjo came across from Africa,

They say the guitar came from Spain

The mandolin it’s from Italy

But they blend in just the same

Lord I love to hear that bluegrass sound

Something about that music goin’ down.

Bluegrass music first definitively adopted an instrument of Hawaiian origin in 1955 when Josh Graves introduced the Dobro into the Flatt and Scruggs sound. Plenty of purists objected, but, as Josh later told me, “It took a while [for people] to accept it, [but] then it just started growing.”

By then the Hawaiian slide steel guitar already had an impressive history, from its origin 1899 with Oahu boarding school student Joseph Kekuku, to the subsequent craze for the instrument in both Hawaii and the U. S. mainland. Around 1925 the three immigrant Dopyera brothers (born in Austria-Hungary) created first Dobro. Country recordings featuring steel guitar by—among others—Cliff Carlisle, and Jimmie Rodgers followed. While working at a factory in Michigan, Tennessean Pete Kirby learned to play from a Hawaiian immigrant named Rudy Waikiki. As “Bashful Brother Oswald” in Roy Acuff’s band, Kirby was the consistent swooping sound of the “resophonic guitar” on the Grand Ole Opry for more than five decades starting in 1939. As a result of the music played by Josh Graves and his steel guitar predecessors, today we are blessed with dobro masters like Jerry Douglas and Rob Ickes with more on the way.

Hawaii’s Big Island— David Gomes

Now we have a second Hawaiian-related instrument—the bass ukulele or U-bass—starting to get noticed by America’s musicians, including bluegrass players.

Among the first—probably the very first—to make one is a neighbor of mine here in North Kohala. David Gomes—born in North Kohala—is a skilled guitar and ukulele luthier. His Portuguese great grandparents immigrated to Hawaii like the Portuguese musicians whose instruments inspired the original ukulele. They came to work the sugar plantations that once were the economic foundation of this district.

David recalls, “One day I went to the Music Exchange store in Waimea.” (This was the same store where Chris Wej would—9 years later—encounter the Kala U-bass). “ I saw a little dog-bone-shaped solid-body Ashbory bass,” continues David, “and realized it had the same scale as a baritone ukulele. The silicone strings didn’t play well, but I thought, ‘If I could get the right strings, I bet I could make a bass ukulele close to that same size.’”

By around 2002 David had made a rough prototype. His friend Kim Sweeney saw it, and immediately ordered one from Dave. “I fell in love with it in a minute,” Kim reported online via the Large Sound website on April 30, 2003. “It is made from curly koa, from a fallen tree, right here in our neck of the woods. When you plug it in it has a real DEEP, rich woody tone!”

More Bass Ukulele History Made On the Big Island: Mike Upton Meets Owen Jones Keoholaumakani Holt, Jr.

David Gomes never aspired to a large-scale instrument business. However, here on this same Big Island—this small dot in the middle of the Pacific Ocean—two residents of California met and came up with their own plan.

One was a luthier, Owen Jones Keoholaumakani Holt, Jr. Noting Owen’s third name, I asked if he had Hawaiian ancestry. “Born on Oahu. Moved to California in 1959, so raised in California,” he replied good naturedly. “Yes, I am of Hawaiian, British, Scandinavian and Chinese ancestry… so Poi Dog!1”

Like David Gomes, Owen Holt, Jr. is a dedicated craftsman always looking for new ideas. Like David, Owen had seen the small Ashbory solid body bass and had, independently, come up with the idea to build a hollow body bass ukulele. Neither he, nor his soon-to-be collaborator, Mike Upton, lived on Hawaii’s Big Island. By chance they met one another here in 2002 for the first time in the community of Kealakekua. It was at an event at sponsored by the Big Island’s Ukulele Guild. As Holt remembers it, Upton was just on a family vacation. Mike Upton worked for the Hohner company (of Hohner harmonica fame), in Santa Rosa, California where he helped develop a successful commercial line of ukuleles called Lanikai. However, he was getting ready to start his own company which he would name Kala.2 And the idea of a bass ukulele intrigued him.

With Holt’s expertise as a luthier and Upton’s connection to the world of commercial distribution, the Kala U-bass was launched in 2009. Musicians from various genres have been delighted by U-basses. These instruments have found homes in country, reggae, pop, and jazz as well as bluegrass. In addition to those mentioned above, U-basses have been given to children too small for an upright bass, used in music therapy for folks who have undergone hand surgery, and played by dedicated bluegrass jam session players who enjoy their portability and ease of playing. David Gomes continues to make high-end, lovingly-crafted bass ukuleles upon request at his North Kohala workshop.

Owen Holt, Jr. tells us, “I’m off and on working on new projects and I may return to selling instruments that I produce. I don’t plan to do any custom builds, so anything that I build will be more or less a semi-production design, but using different wood combinations. I do sell the Pahoehoe Bass string sets in different sizes and colors on bassuke.com.”

Kala founder Mike Upton plays his U-bass in folk/bluegrass settings, and serves as president of his company which makes 15 or 20 instrument models, has 55 employees at its facilities in Petaluma, CA, Honolulu, and Ashland, VA. It sells around 10,000 instruments a year internationally.

So the question to be answered is this. Will bluegrass musicians continue to lug around their huge, beautiful-sounding classic upright basses? Will bluegrass fans insist they don’t want anything that looks so different from what they’ve grown used to, even if it sounds good? Or will Gracie Meador’s wish come true: That U-basses will find a place of respect on festival stages such that her hands will be able to enjoy the short scale and easy action of her favorite instrument?

As Yogi Berra may have said, “Prediction is hard. Especially about the future!”