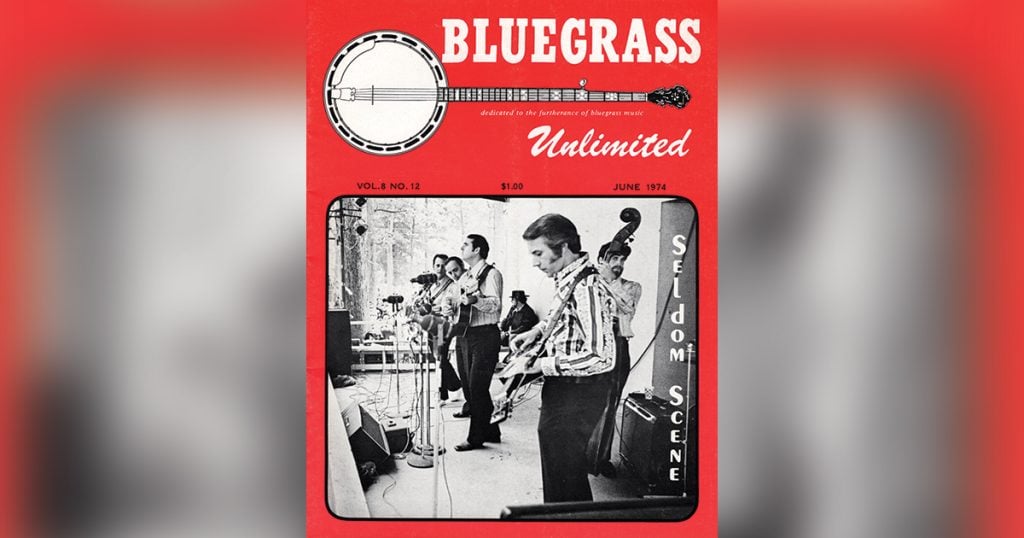

Home > Articles > The Archives > The Seldom Scene as Heard

The Seldom Scene as Heard

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1974, Volume 8, Number 12

The following conversation occurred after The Seldom Scene had finished their evening concert at the Red Fox restaurant in Bethesda, Maryland. It’s their story—it’s told the way they want to tell it in the hope that the reader may gain a valuable insight into what makes for a successful and viable group.

I began the conversation with a view toward developing a story on their non-musical professions, since each of them are employed full-time in other careers.

John Starling: (Lead singer and guitar) When you talk about this “second career” thing, I’d like to play that down—to this degree. We are in to music full-time, psychologically. We don’t want anybody to think we’re not trying. We’re trying to do the best we can and we want to try to compete on an equal footing with everybody else. The one thing about us is that we don’t play as much as other bands and the advantage that might have is that when we do play, we’re a little fresher maybe.

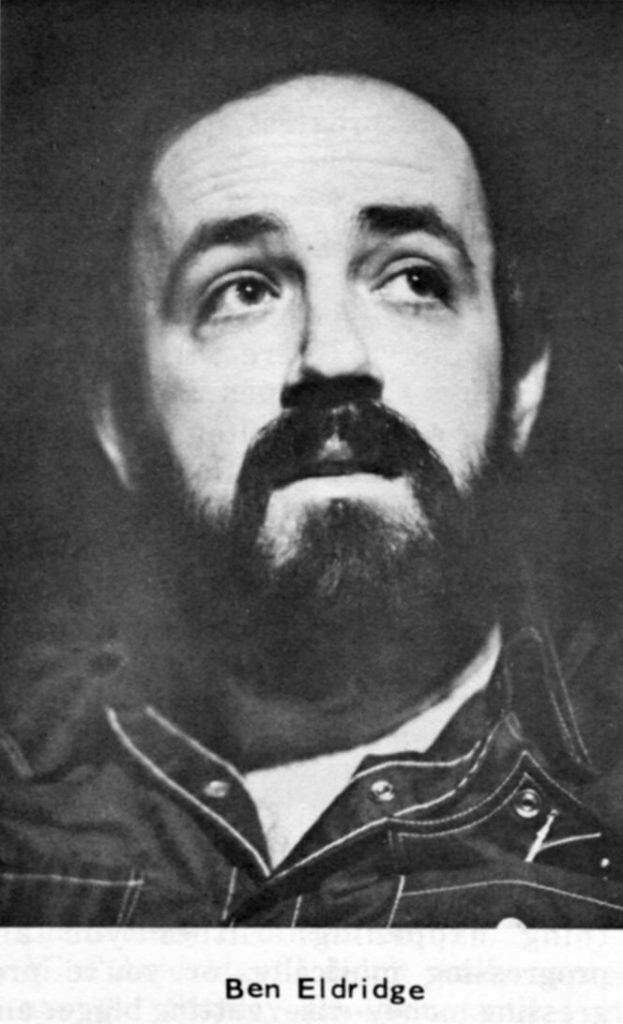

Ben Eldridge: (Banjo) It’s more fun.

John Starling: But that’s something we don’t plan. For instance, if you have fifty songs and you do them five times a week-on the fifth time it becomes a drag.

John Duffey: (Mandolin, tenor and lead singer) Even the third time!

Pat: It would appear that monotony or boredom would set in, however well you performed.

Tom Gray: (Bass-occasionally lead singer but mainly bass on quartets) That’s true. I know ten years ago when I played with the Country Gentlemen, we had gotten to a point where I was getting tired of playing as many shows as we did—and in those days we weren’t as busy as they are now. I think that if you don’t have to play—if you don’t have to always go out and do your best show to a different crowd every night, I think you will enjoy it more because you feel like you’re creating something. Like with us, I think we’re in a perfect situation to develop ourselves musically because we only play one night a week at the Red Fox. The crowd knows that and they appreciate us for what we do there.

Ben Eldridge: It kind of takes the pressure off, really. I think that is one of the neat things about the group.

John Starling: Although I think it’s interesting that we do something else, I would rather be accepted on the basis of our music. I’d rather be judged on what we do rather than on what we don’t do.

Mike Auldridge: (Dobro and baritone singer) Yes, it’s kind of embarrasing when people say, “You guys are really good—it’s hard to believe that this is just your hobby!” The thing is that we probably work as hard at it as any full-time band.

Pat Mahoney: Is it a hobby?

Ben Eldridge: Sure it’s a hobby.

Mike Auldridge: I think it’s something we would do even if we weren’t playing in public. We would sit around and pick; then it would be a hobby. But when we’re working at it seriously, you can’t really call it a hobby.

John Duffey: It’s a fairly good-paying hobby, but the point is, it’s something we all like to do.

Ben Eldridge: I don’t believe you said that!

Pat Mahoney: Do you have anything else—what other things occupy your time?

John Starling: You know, it’s nice to be the universal man. But you get to a certain age when you’re pretty busy in your day job and you really don’t have time for one other outside interest, if it’s as big as this one. I used to play a lot of golf. I used to play cards. I’ve just given up most of the other interests. So the point now is that if I quit playing music there would be a big gap. I hardly watch TV anymore. I usually turn on the record player.

Pat Mahoney: How about you Tom, what other interests do you have? I know you have quite a substantial record collection.

Tom Gray: Yes, I still have it, but I don’t collect as much as I used to. I just don’t have time to listen to the music as much now. I used to try to dig up old records. I used to bid in auctions. Now I’m active in scouting.

Ben Eldridge: Now music is just about all I do other than normal family activities. One of the things I used to really like to do was play chess and I was just as nutty about that as music today.

John Duffey: Bowling, playing ball. Any kind, baseball, softball, football. If someone calls me and says, “Hey there’s gonna be a ball game this afternoon”. I’ll say, “Where and what time!!? I used to fool with automobiles all the time. I used to race. I’ve got trophies at home—drag racing. I used to build hot rods. Nowadays the cars have gotten so complicated with all the pollution controls, etc. I can’t keep up with them.

Pat Mahoney: What got you into the music instrument repair area? Did something of yours break and you figured you would repair it?

John Duffey: That’s a good question, I really don’t know. One time, years ago, the post office had their annual auction of lost-in-the-mail, unclaimed items which were undeliverable, etc. I bought a box of stuff (which was about three feet tall) of broken instruments. That’s how I got my first mandolin. There was a Kalamazoo in there, and it had only one crack in it. I took those things home and I decided I would try to put them together like my father used to do. In high school there was like fifteen guitar players and one bass player, which made a rather rotten band, not much variation. The bass player’s parents had this mandolin which I borrowed.

Pat Mahoney: What instrument did you start with? Did you start playing mandolin before you played guitar?

John Duffey: No, I was one of the fifteen guitar players!

Pat Mahoney: Did anyone not start with a guitar?

John Duffey: Actually, I started with a banjo.

Tom Gray: I started with an accordian.

Ben Eldridge: I started with a Gene Autry “Melody Ranch” guitar from Sears & Roebuck. There was a fellow across the street from me named Nicky Valdrigi. He was about two and a half years older than me. He was kind of my idol, and I used to follow him around in my neighborhood. He taught me how to play baseball, etc. He played the accordian. That’s what I wanted to play because Nicky played the accordion. My folks just couldn’t afford the $120 for an accordian. They could afford about a tenth of that and I wound up with a $12 Gene Autry guitar but I always liked country music, so everything worked out O.K.

Pat Mahoney: When you mentioned a banjo John, did you mean a tenor or a 5-string?

John Duffey: 5-string, but I just couldn’t seem to get anything out of it.

Mike Auldridge: I’m really lucky because I’m doing exactly what I’ve always wanted to do. I have always been interested in art, and I’m an artist for the newspaper, (Star-News in Washington, DC) and music. The only other interests I have is antique cars. I’m an old car enthusiast. I like old cars but right now I don’t have a garage to house them in. I’m planning to get something soon. I’m like John (Starling) in giving up golf. I haven’t painted anything recently. Of course working in art all day, I really don’t feel like coming home and painting. That’s like if I were playing music all day; I don’t think I would come home and pick.

Ben Eldridge: Mike did the cover for our second album.

Mike Auldridge: Yes, the cover for ACT II was a thing I did in school, a lithograph print.

John Starling: Ebo Walker picked it out!

Mike Auldridge: He did. I gave it to John Starling and he hung it in his house. Ebo Walker saw it and said, “Hey man, that would make a neat album cover.” I grew up with the big band sound. My older brother was a nut on Benny Goodman, etc. The first person I remember being interested in musically was Gene Krupa. You were talking a while ago about the first instrument you started playing—the first instrument I started with was a guitar, but the first instrument I bought was a banjo. I didn’t know the difference (about banjos)—so I went to a pawn shop and bought a four string banjo trying to figure out how to play bluegrass on it! The first instrument I really played was a guitar.

Pat Mahoney: What brought you to the Dobro?

Mike Auldridge: I guess the thing that really caught me was-like, my uncle used to play Dobro and I used to hear him a little bit here and there.

Pat Mahoney: Did he play professionally?

Mike Auldridge: Yes, he played with Jimmy Rodgers. He wrote “Treasures Untold” and “Dear Old Sunny South by the Sea”. Doc Watson put it on one of his albums. My uncle was the first person I ever saw who played Dobro. He played an old-timey style. I heard Buck Graves when he was with Wilma Lee and Stoney Cooper. That’s when I got interested.

Pat Mahoney: What part of the country are each of you from?

John Duffey: Born in Washington, DC.

Ben Eldridge: Richmond, Virginia.

Tom Gray: I was born in Chicago, but I was reared here in the Washington area.

John Starling: Lexington, Virginia.

Mike Auldridge: Washington, DC.

Pat Mahoney: There’s a certain style you have as a group. How important is it?

Ben Eldridge: I think it’s an accident.

Mike Auldridge: Yes, I think it’s a function of the guys who are in the band. I think a lot of what we have that the early Country Gentlemen had is because of John Duffey. Part of our sound is John Starling’s influence with the selection of the material.

John Duffey: Background taste has a lot to do with Mike personally. I say this because I listened to Dick Cerri play one of the “side by sides” on radio the other day. He played “Heaven”—which Flatt and Scruggs did. Then he played our recording of it. We were listening to the background; both records have Dobro on them. On Flatt and Scruggs’ version (and with no offense to anybody) it had a lot of “hot” licks, that’s the easiest way I can think to describe it—in a song that really doesn’t call for “hot” licks. And in Mike’s background, you know, there was the right thing at the right time.

Mike Auldridge: My head’s gonna swell because Eddie Adcock said something to me one time that made a lot of sense. He said, “The next best thing to having taste is not being too good!” You know? It’s better to have a guy that plays what he knows well, and at the right time. He might not know a lot of variations, etc.

Pat Mahoney: Not to interrupt the train of thought, but did you or have you listened a lot to Pete Kirby’s Dobro?

Mike Auldridge: No, I’ve paid more attention to Buck Graves.

John Starling: I object to the idea I’ve just been sitting here thinking about it—I object that I’m the one responsible for the material. Because that’s just not true. It might seem that way in a lot of ways because I’m the one who has to learn the words to a lot of things. For example, on the last album, Ben said,“Go learn ‘Muddy Waters’.” Tom was the one that got us into doing “Paradise.”

Ben Eldridge: I don’t want to lay claim to the Redskin song!

John Duffey: I’ll lay claim into irritating you into doing that.

Mike Auldridge: The reason I said that a while ago, was because of the five of us, you (John Starling) are more influenced by the other kinds of music. My musical tastes are really narrow, compared to yours. I would never have found say “Rider” because I never have listened that much to rock music.

John Starling: To keep from getting paranoid, you know. I’m not a super picker, all these other guys are. I feel like in order to contribute my part (and I enjoy it too) I enjoy going out and trying to find material. I don’t always find it. Like right now I’m at a big zero.

Ben Eldridge: But you are at a very enthusiastic stage right now, you know, when you come home from work you start thinking about music, playing records, etc. I may just be speaking for myself, but I don’t do that much anymore.

John Duffey: He (John Starling) does what I used to do fifteen years ago because nobody else did it. I enjoy having somebody else do it.

Ben Eldridge: That’s why you have influence in picking material because you listen and spend a lot more time with music.

Mike Auldridge: I think it’s a combination of John Starling’s attitude toward contemporary material and John Duffey and Tom Gray’s attitude toward the older, traditional material. It’s kind of a mixture Ben and I are along for the ride as far as material goes.

John Starling: I’d like to experiment with different rhythms with Tom Gray if I could get the lick right on the guitar. There shouldn’t be any type of material that we would be afraid to try. Basically that’s what keeps a band growing, you know. People sometimes say “Hey man, this is a great song. It just fits you all perfectly.” Well I may not be too interested in hearing it if it “fits us perfectly”.

Pat Mahoney: Why not?

John Starling: Well I would rather hear a good song and decide for myself if we can do it. If you’ve been together for three years, you tend to know the kind of song you can do well and the kind of song you won’t do well.

Ben Eldridge: John Starling and I see each other a lot and we listen to the same kind of songs, etc. Maybe we will hear something that we both like but I don’t think any of us listen to a song with the idea of,“How can we adapt the song to fit us, but rather—is it a good song? That’s the way I felt about “Muddy Waters”—I heard the song and I thought, “Wow, that’s a nifty tune.” The same way with “(Raised by the) Railroad Line”.

John Duffey: Or wouldn’t it be fun to do.

Pat Mahoney: Alright then, what we are saying is that there’s a universality in music, isn’t there? Or is there?

Mike Auldridge: On our Dobro album we are getting ready to cut, I’m hoping to do “Killing Me Softly” which is the last thing you would think of putting on a bluegrass album.

Tom Gray: It’s good overall music done with bluegrass instruments which is what our style is all about.

John Starling: A guy wrote a review in the Washington Post and he said it better. It’s what we’re into really. He said we are using bluegrass more as a method, rather than a fixed tradition—which in the long run, is what all bluegrass bands do except (Bill)Monroe and (Ralph)Stanley, as far as I’m concerned. It’s just a matter of degree.

Ben Eldridge to John Starling: I don’t agree with you. There aren’t that many bluegrass bands that do that.

John Starling: The Dillards do, the New Grass Revival.

Ben Eldridge: Yes, you can name a half a dozen bands, but a half a dozen out of a hundred.

Mike Auldridge: That’s right, most are traditional bluegrass bands.

Pat Mahoney: Do people give you songs ? Written or taped?

John Starling: We solicit them actively.

Mike Auldridge: We’re interested in hearing anything.

John Starling: There’s a lot of good song writers around, but what so many song writers are into now, and I could mention half a dozen; They’re into lyrics—the lyrics are everything. But for a group, it makes it a little tough because we have to have songs that have a fairly strong melody line because they’re more fun for us to play. They’re better stage songs. There’s a lot of good writers who are writing neat lyrics and I listen to the song but the tune stinks. It would be nice for one person to do, but there’s just not that much there in the way of a “sock-o” chorus or something that makes a good group song that you can do over and over again and not get tired of it and also not put the audience to sleep. I think young people are interested in lyrics that make some sense and are relevant to what’s happening today. But it’s hard to find good lyrics like that and at the same time a good tune.

Pat Mahoney: John Duffey and I were talking a little bit about singing. What makes it or helps make it? Of course, tone and timbre are important, but enunciation is also important. I can hear every word John Starling is singing.

John Duffey: Yes, but you just can’t enunciate “Molly and Tenbrooks”!

John Starling: I think enunciation is important, but it’s amazing to me how many hit songs that have been made where you couldn’t understand what the guy was saying.

The thing I like about our group is we don’t have any gimmicks—we don’t play a hot lick just because there’s a hot lick to play. We do simple songs and we do them fairly simple. Basically if you’ve got a good vocal sound that’s all you need to do. Some groups use vocals just to highlight their picking. They realize their picking is their strong point and they sing just enough to avoid the monotony of all instrumentals. With us, everything is done to augment our singing.

Before I started singing with John Duffey, I used to phrase a certain way—and I still do when I’m singing by myself, but when you start singing in a trio, (and I’m sure John has changed a couple of things that he used to do with Charlie [Waller] just because it blended better) but when we first started singing together, we didn’t blend very well, because we were “fighting” each other—we wanted to phrase things differently. After a while, after you’ve done a song for a while, you subconsciously learn to phrase differently. That’s what makes trios begin to sound “together”.

Pat Mahoney: You can tell when you’ve got the crowd, can’t you? Because when you do slow down and get into a good trio, you can hear the audience quiet down. Sometimes they’re chattering at 90 miles an hour and you could sing the best song on earth and nobody would seem to give a damn!

Ben Eldridge: You know, something that bugs me in a way is, sometimes we’ll play some solid bluegrass like some of the Stanley’s stuff. “Heart to Heart (Think of What You’ve Done)” things I love, and the audience is just kind of indifferent. But you can play “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” and “Orange Blossom Special” and they go ‘bananas’.

They do seem to like the slow trio things. A lot of the old bluegrass songs-maybe it’s just the way we play them. I don’t know, but I don’t think we play them all that bad. They just don’t seem to stir anybody up. It bothers me some because I get stirred up just playing them. Tonight when we did “Footprints in the Snow” I really got turned on.

Pat Mahoney: Do the rest of you get that same impression when you watch the audience? Or do you watch the audience?

Mike Auldridge: You don’t watch the audience, but you listen to them.

John Duffey: I watch them a lot.

John Starling: When we play a set, we pick the first two or three songs we’re going to do and at least get some continuity in the first three and then what we like to do is just kind of “float” from there. It’s a matter of the mood of the crowd and the way we feel. One song just sort of leads into another. We try to keep from doing a whole bunch of fast or slow things in a row. It’s a matter of feeling the music. You can get into a rut that way. It used to be that you could go to one park show and that was it. You saw all the bands and could predict that they would do the same sets all summer long. The same sets. Exactly the same songs and in exactly the same order. And I don’t understand, especially with groups that go on tour, you know, like some of the big rock groups—they’ll work up a 12-song set—they’ll do the same set in Cleveland, Chicago, and that’s great because it’s a different audience, but they’re bound to get sick of it before they’re through. We’re just now beginning to get enough material where we can go out and just sort of “float.”

Mike Auldridge: If you play off the top of your head, you get a lot more enthusiasm in the band. But I think the band’s enthusiasm is really gauged by the audience. We can play to a “live” crowd and that makes you play much better and you think of neater things.

Pat Mahoney: Speaking of the audience, what do people ask you to play—your own stuff or do you get a mix-other artists, or does everybody ask for Seldom Scene material?

John Duffey: Most of the requests are for the things we’ve done. Just to use and expression, “numbers we’re famous for”, like they want to hear Mike play “Tennessee Stud”—they want to hear “The City of New Orleans’’—and to this day I’ll never know why they always ask us for “Fox on the Run” and we’ve never recorded it.

John Starling: I think the audience is getting familiar with our material because they’ve stopped asking for “Rocky Top”. They don’t ask for that one anymore because they know we don’t do it. They don’t ask for “Orange Blossom Special” because they don’t see a fiddle up there—although occasionally someone will holler for it.

Pat Mahoney: Have you ever had a “dead” crowd?

John Duffey: Yes, occasionally.

Mike Auldridge: Occasionally it’s our fault too.

John Duffey: Yes, it’s our job to liven the audience up. The audience didn’t pay to come in and pep us up.

John Starling: It gets back to this business of, if we wanted to plan a “super” set, really designed to get everybody off, we could do it, but we’d rather not. It’s more fun for us to kind of float free. The problem with that is that it makes for “super” spontaneous sets or complete disasters! I mean, sometimes you just can’t get any continuity in the music and you just can’t seem to get to them. You go on and play for forty minutes or so and Zap! you feel it, you know you didn’t have the audience with you.

Mike Auldridge: Right, you didn’t think of the right songs.

John Duffey: Yes, after you leave the stage, you think of fifteen numbers you should have done.

Tom Gray: I think generally the audiences like the spontaneity that we have. It amuses them when they see somebody trying something that maybe doesn’t work, etc.

John Duffey: Well as you go along you can experiment. Like I must have played the (Tennessee) Stud at least seventy-five different ways, you know, and like I’ll try something one night and it’ll come off good and I’ll go off in the corner and pat myself on the back and I might try the same thing the next week and just blow it!

Pat Mahoney: Isn’t that an element of bluegrass? Hasn’t someone called it Country Jazz or something like that?

Mike Auldridge: You mean improvised music?

Pat Mahoney: Yes.

Ben Eldridge: Yes, I think it’s a lot like Dixieland.

Pat Mahoney: It’s free, it doesn’t have too much form.

Tom Gray: It has a simple form, but it gives you a lot of room. When it’s somebody’s turn for a break, he’s got a pretty free hand.

Ben Eldridge to Tom Gray: Do you sort of agree to that analogy? You’ve played Dixieland music.

Tom Gray: I do in general, but I’d say that bluegrass musicians take their music more seriously than Dixieland musicians.

Pat Mahoney: You do?

Tom Gray: Oh yes, I think part of it is because of the boisterous, busyness of Dixieland. People make mistakes all the time and it doesn’t seem to bother anybody. If I go to the wrong chord (in bluegrass), I start getting dirty looks. I had a little trouble on “Sweet Baby James” tonight.

John Starling: We did it a little faster tonight, but there was one point there at the beginning which didn’t come off right. You know this whole thing about bluegrass and where it’s going to go….

Pat Mahoney: I didn’t ask that.

John Starling: I was going to tell you anyway. I wish we could write more than we do. Being able to write a song when you want to isn’t that easy. None of us are very prolific. One of us will come up with something occasionally. We would like to use original material. Bluegrass has got to have it’s own source of material to stay viable.

Ben Eldridge: I think that’s one of the things that has happened to Dixieland music.

Tom Gray: They’ve not had any new songs in the last twenty-five years. I think that’s what has gotten bluegrass off the ground—new material. And the people are willing to sing songs from other sources of music and not feel like a fool when they do it. Ten years ago if somebody got up there and sang a rock song, everyone would scream, foul.

Ben Eldridge: Yes, but you guys (meaning the Country Gentlemen) were doing that about ten years ago. But I guess you had a lot of abuse heaped on you from the bluegrass people too.

John Starling: Most of the groups that are really making it though are—the ones that are right at the top—are the ones who are doing original stuff. Look at the Osbornes—everything they do is new and original. They don’t even touch something that’s hot, even in the country field. They like original stuff. They may put on their album an old song or two or something from another type of music, but basically their singles and the material they put out for consumption are songs that are original. Maybe they didn’t write them, but Paul Craft or somebody wrote for them. That keeps generating new music, you know, like “Rocky Top” has become a standard now—five years ago it was unheard of—that’s what has got to keep happening. I think in the long run, the group that ends up making it big is going to use bluegrass as a method rather than a fixed tradition—may be use less of it than we do. I hope it remains acoustic. I’d like to see some acoustic group really hit it big like the Kingston Trio did but with more “soul”.

Pat Mahoney: Should it be the most popular music in the world—what would happen to it? Is it destined to be the next big thing?

Mike Auldridge: I don’t see why not—all it takes is enough people who like it. If we like it, what’s it to keep the younger generation from liking it? It appeals to people who aren’t pickers—it’s not limited.

John Starling: I think we sell a lot of rock musicians short—there are a hell of a lot of good pickers that are in rock.

John Duffey: That I agree with. A large majority of them can’t sing—they scream rather nicely, though.

Mike Auldridge: The thing that brought that home to me was Clarence White whom I thought was the most fantastic guitar player. I first met him when he was playing acoustic guitar and the guy just knocked me out. I thought, My God! I just can’t believe this guy’s timing. When I saw him on stage playing guitar with the Byrds, he was probably doing just as good material, but the noise level of everybody else diminished my appreciation; whereas in bluegrass you kind of showcase each person individually. I think that’s the big difference.

John Starling: Ben, I listen to today’s country music being played and they just don’t seem to have any lasting value. The songs Hank Williams wrote-“I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”. Those words will live forever.

John Duffey: The words were simpler. They were very simple songs. They are taking songs now that they call country music and the words are just terrible. But somebody has gotten the bright idea to put in more chord changes. And so now you just have sickening songs with more chords in them. It’s really regressed.

Mike Auldridge: I think two things have happened. One, people used to be kind of ashamed to admit they were emotional about music. In country music they just pour it all out, you know, and they sing songs about things that most people would rather just not talk about in their own lives. The other thing is that country music lyrics are more relevant to what is happening in the world, rather that what’s happening back in the sticks.

John Starling: There’s some good song writers today. Tom T. Hall is a good song writer.

John Duffey: He comes up with a lot of neat things.

John Starling: There’s a difference to me when it comes to country music stars, who are just “stars for the day”, and people who are becoming legends in their own time. The artists who are becoming legends in their own time are writing and singing good songs and still making hits out of them. The standard formula nowadays is to write a ten cent song—and there are a lot of people doing that—but the Tom T. Halls, the Merle Haggards, are writing good material and it will last a long time.

Pat Mahoney: What does the future hold for the Seldom Scene?

John Starling: I don’t know. I’m a cautious soul. You can always work things out. Right now we are trying to get John Duffey on an airplane. We plan to drug him.

John Duffey: You may not live that long.

John Starling: I think it would take an awful lot to get any degree of national exposure—we’re not a gimicky band.

Pat Mahoney: Do you want to be nationally known and recognized?

John Starling: Well, I don’t know. You know, you talk to people who have made it. They went through years of struggle wishing they could become a star and when they got to be one, they had lost their privacy. Now they would like to go off somewhere and be alone sometimes. You may defeat yourself in the long run.

Mike Auldridge: I think the main thing—or in my case anyway—there’s nothing I’d rather do than pick. I think I could do it at least 18 hours a day and never get sick of it. But the main thing is security. It’s scary to give up your job.

Pat Mahoney: It’s a fragile business.

Mike Auldridge: That’s right. You might be hot stuff for six months or a year and be “dead” the next year. It’s kind of tough to give up a job that you have a lot of security in; unless you’re assured you would be making big money in a couple of years.

Pat Mahoney: Would $50,000 apiece take you away from your daily chores?

Mike Auldridge: Well, say you could go out and make $50 or $60 thousand for a couple of years—then you would have to come back and look for another job.

Ben Eldridge: That’s alright, I’d do it.

Tom Gray: At that price, I think I would be tempted to do it.

Mike Auldridge: Yeah, one would be tempted to do it.

Ben Eldridge: I’d direct a chorus of trained fleas for a couple of years for that price!

Pat Mahoney: Is it economics alone?

Tom Gray: It’s economics.

Mike Auldridge: For one thing, when you talk about $50,000 per man—you would be amazed how much is eaten up by just traveling. We might end up making about what we’re making now. It’s really an expensive way to live.

John Starling: That’s a question we just can’t answer.

Pat Mahoney: Well, it is an unfair question, but what is your future anyway?

Mike Auldridge: We really haven’t planned anything definite. We are going to “play it by ear.”

John Duffey: It’s more than economics with me. I’d be a nervous wreck just to keep on going day after day from one place to another.

Mike Auldridge: Well, if you’re making a lot of money, you don’t have to do that.

John Duffey: Well, believe it or don’t, I’d like to be rich like the next guy, too. I guess to me though, money isn’t everything—maybe it should be, but it isn’t.

Mike Auldridge: What is everything?

John Duffey: Just plain being happy.

Mike Auldridge: Is it a too hectic life—is that what you mean?

John Duffey: Yes, it’s a hectic life. I used to wonder, years ago, why certain country music stars drank booze or I’d wonder why you couldn’t get these guys out of their bus to do their show because they would be too drunk to play. After you’re in it for a while, you find out why they’re that way. It’s just a hell of a life—it’s boredom.

Mike Auldridge: It’s a grind.

John Duffey: Boredom is a great part of it. When you’re doing the same show here, there, and in the next town—that’s boredom. The boredom of being on the road, trying to amuse yourself without going stark, raving mad. Then they say, “Well, there’s a liquor store in every town. And maybe if I don’t feel anything—and not realize anything, it won’t matter.” So you find out why they turn into alcoholics, or junkies, or whatever.

John Starling: The problem with this is that it’s sort of a psychological thing. If you’re in a group or band and you start making some progress, there are high points along the way—high points emotionally, like when you are playing in a good place to a good crowd, or for us, like playing Constitution Hall, or getting to pick with somebody that you’ve always admired. There are all kinds of little things that happen. After a while they come a little less often. Let me give you an example. Linda Ronstadt was in town several months ago when we did a show down at Callaway, Maryland. She got up on stage and did some stuff with us. I’ve always admired her singing—I think she’s great. Having her get up on stage and sing with us was a big thrill. I went through about three weeks there where I thought,“What am I going to follow that with?” That’s the type of thing I am talking about. There always has to be-to keep a band viable—something happening. Either you are progressing musically, or you’re progressing money-wise; getting bigger and better gigs or something happens to keep you going. I’m sure there’s a point there—like if you were the Grateful Dead and making $30,000 a show, and you’ve got all the fame (in fact you don’t want as much as you’ve got) where there’s a big let-down, emotionally. That’s why the Beatles probably all split up and went off and did something on their own. Where could they go from where they were?

Tom Gray: I have always liked the Blue Sky Boys. But I realize that today one has to have something more than that to be a successful musician. I just happen to like that, and music in that style—the Louvin Brothers, and James and Martha Carson. Ralph Stanley is doing a lot of good things that I like these days. He seems to be getting more and more into his roots, which I think is great.

Ben Eldridge: As far as bluegrass groups go, I think the old Flatt and Scruggs group are my all-time favorites. They were the people I really started listening to when I was in high school. I had their records and I used to listen to them everyday. In fact I learned how to play by slowing Earl Scruggs’ 45 rpm records down to 33 1/3. I think all their stuff was “super”. My other preference was John Duffey, Tom Gray, Charlie Waller, and Eddie Adcock. When I first moved up here, I spent many a night down at the Shamrock (Restaurant), listening to those guys pick and sing. When it comes to. banjo pickers, Earl (Scruggs) has always been my number one man. I’ve always liked Alan Shelton, Sonny Osborne. And about 1963 I heard Bill Keith for the first time and I just couldn’t believe what he was doing with a banjo.

Mike Auldridge: Chromatic?

Ben Eldridge: Yes, Keith plays with a lilt and feeling that I’ve never heard anyone else quite capture. I’m a real fan of Bill Emerson, too. He’s another great one. He and Cliff (Waldron) started playing at the Red Fox (Inn) in 1967. I guess I’m the oldest Red Fox bluegrass patron going, because I was there the first night they ever had it. I don’t think I’ve missed more than a dozen times (one night a week) since then. I’ve stolen many a lick there.

John Duffey: Talking about Bill Keith, I remember one time he came down to the Shamrock and got up and played with us (The Country Gentlemen).

Ben Eldridge: I was there that night.

John Duffey: And he wanted to come over to my house. And he said, “I’d like to learn some timing and things like that.” And I said, “Wow, what you’re doing is over my head—and you’re asking me?!” I don’t know, as groups go. I’m still a fan of the Osborne Brothers. Regardless of whether they’re plugged in or not. If they plug in, I don’t even hear it. I hear what they sing. They came out with “Making Plans” a few years back. I was riding down the road with the radio on and—of course then you would seldom hear any kind of bluegrass—but that thing came on the air and I had a chill attack.

Another group I used to like to hear sing was the Browns. They had a fabulous sound. Instrumentally, I’d like to be Chet Atkins or Jethro Burns. Jethro’s fantastic. He probably knows more than the five of us put together. My first experience with him was when we played a show thirteen years ago at Oak Leaf Park in Luray, Virginia. Homer and Jethro were the main attractions on that show. I’d sit around and drool over what he was doing. They would stand there and talk to you and all the time they would be playing some absolutely wild stuff—Homer’s playing nine chords for every beat. It was just amazing. I always liked Flatt and Scruggs.

Ben Eldridge to John Duffey: Did (Bill)Monroe sort of influence the way you play mandolin? I used to think that you had a lot of that same feeling.

John Duffey: Very early Monroe did something for me that he doesn’t know he did. I had this record which has always been a favorite of mine called “When You Are Lonely”. The label said Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys; I figured Bill Monroe was singing. I could hear this fantastic mandolin along with the singing. So I used to stand in front of the mirror and I’d sing the song and watch my fingers, so I didn’t have to look down, and I would stand in front of that mirror and try to sing something and play behind it. I guess after standing in front of that mirror for so long, I finally learned how to do it. Years later I realized that the vocal was done by Lester Flatt.

Later on, with The Country Gentlemen, I put it to good use because we had only four men. So if somebody didn’t do something behind the guitar and bass while we were singing, it left a big hole in our sound. It didn’t take me long to realize that I couldn’t beat Monroe at his own bag so I had to figure out something else. That’s when I started doing different things which I guess other people have copied. The only thing is they can do it better than I can now.

Pat Mahoney: How about the Jesse McReynolds style?

John Duffey: That’s another situation, the backwards roll with a flat pick or whatever you want to call it—you can’t beat him at that.

Pat Mahoney: I talked with Jesse about that and he said he liked to have worn his fingers out learning it.

John Duffey: You’ve got to be yourself.

Pat Mahoney: I wasn’t sure he was the first to use that style. Did he originate it?

John Duffey: As far as I know, he was the first one I ever heard do it. The first thing a lot of people thought was that he was fingerpicking the mandolin. If you listened to it clearly, you would have said well if he’s fingerpicking it, he’s doing it backwards! Then when I eventually saw him, I saw the flatpicking. I’ve heard a lot of other people who can do it, but if you put them all behind a curtain, I believe you could tell which one was Jesse.

Pat Mahoney: Mike, who influenced you?

Mike Auldridge: I’ve just been trying to think; that’s really a hard question.

John Duffey: You really admired me. Yuk, Yuk!

Mike Auldridge: I wasn’t really thinking in terms of Dobro players because as far as Dobro goes there has been only one person, to me. Buck Graves. When I first started playing, I tried to do everything Buck did, but like John (Duffey) says, after a while you reach a conclusion you’ve got to be yourself, and you play what’s in you, it’s an emotional thing. I can’t do what Buck does because he’s got a certain feel—like a blues thing—which I don’t have. But as far as influences, I’m like Ben—when I first started getting into bluegrass, Flatt and Scruggs have always had that certain sound that I really loved. For some reason (Bill) Monroe didn’t get to me. It took a couple of years to appreciate Monroe whereas I fell in love with Flatt and Scruggs’ sound right at the beginning. Merle Haggard, I think, is one of the greatest talents in country music. His taste is—like he did an album of Jimmy Rodgers, “Same Train, Different Time”. To me that’s about the all-time great album. George Jones is a master of phrasing. For groups I would say the early Flatt and Scruggs; the early Country Gentlemen material; and also I’ve always been love with the trio singing and like John Duffey I was always an Osborne Brothers freak.

Ben Eldridge: You know I always liked the Stanley Brothers too.

Mike Auldridge: I didn’t really appreciate the Stanley Brothers until I met John Starling.

John Duffey: I appreciated them. They were one of the few groups I ever drove out of the way to see.

John Starling: As far as old bands are concerned, I was a Stanleys freak. I liked them all but the Stanley Brothers to me were the definition of bluegrass. As far as guitar players, Clarence White was the definition of a bluegrass guitar picker. I like the New Grass Revival. I like the concept of what they are doing. They are basically doing the same thing we’re doing—they are using bluegrass as a method, but are going in a different direction. They are doing it well and they are doing it without a whole lot of gimmicks or frills. I think Sam Bush and Courtney Johnson and all of those guys—they’re just playing the kind of music they like to play. They are using acoustic instruments and they are doing it well. I admire them for it. They’re on the road a lot and while someone is driving, they sit in the back of the car and jam. And they basically just work this jamming up into some sort of program. I have a feeling it may go over a lot of people’s heads, you know, but that’s something else.

As far as singers, George Jones. I wish I could sing with the soul he has. I like girl singers. That Rose Maddox album is a good album—the old Capitol album. Maybe we will have more and more girls getting into it.

Pat Mahoney: Do you ever play for musicians?

Mike Auldridge: I think we play for ourselves.

Pat Mahoney: When a musician comes into the Red Fox, does that “put you on”?

John Duffey: I stopped that fourteen years ago.

Ben Eldridge: I have a tendency to be really careful when certain banjo players visit the Red Fox.

Mike Auldridge: I think it makes you want to pick a little better, but basically I play for myself.

Ben Eldridge: John (Duffey), you can say what you will, but that night

(Bill) Monroe was in there.

John Duffey: No, I was just my same self. I made no more or no less mistakes than I would ordinarily.

John Starling: I heard Bill Monroe say once that bluegrass is a “competition kind of music”. You know that if the band out there just before you is good, and the one coming on behind you is good, you’ve got to go out and sell yourself. I think everyone feels that at festivals, etc., but I don’t think it should get to the point where bands dislike each other. There’s room in this music for everybody.

Mike Auldridge: I used to think.—Wouldn’t it be neat to play with Flatt and Scruggs or somebody like that—but there’s no other band that I would rather play with than the Seldom Scene. We’re doing exactly what I like.

John Starling: That pretty much describes the way I feel too.

John Duffey: You can say what you want—and talk about other people and you can respect or admire others—and you can call it conceited if you want, but if you get right down to the nitty-gritty, we’re just simply ourselves! Which I don’t think is a bad thing to say.

Mike Auldridge: You’ve got to believe in what you’re doing in order to sell yourself and I think we do. I don’t think it’s a conceited thing at all.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Loved this article.

Original Country Gentlemen and the original 5 of the Seldom Scene DID IMHO save bluegrass from extinction.

Going into other genres with their styles such as Bob Dylan Baby Blue and Tim Hardin’s If I were a Carpenter

and the CG’s Matterhorn were a refreshment.Duffey’s passing away in 1996 was a major loss and then Aldridge\and Starling and the great sound was gone.