Home > Articles > The Archives > The Rebirth of a Bluegrass Band: California

The Rebirth of a Bluegrass Band: California

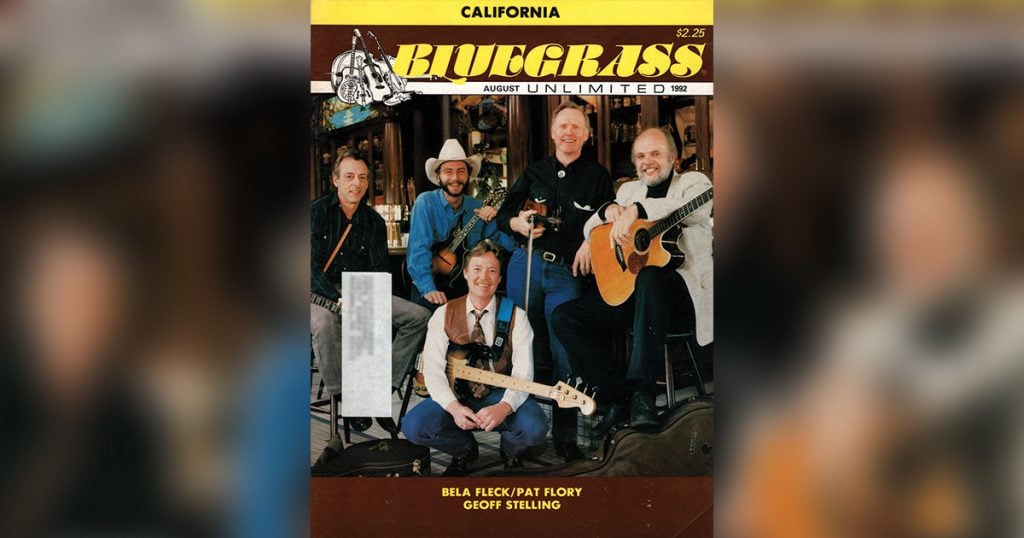

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1992, Volume 27, Number 2

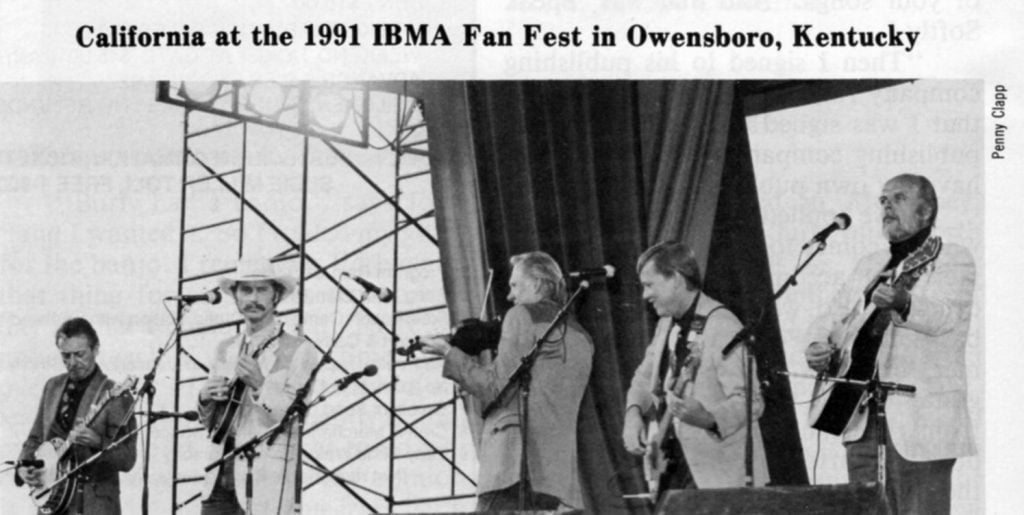

California is Byron Berline, champion fiddler; Dan Crary, flatpicking guitar master; John Hickman, banjo legend; Steve Spurgin, hit songwriter, vocalist and bassist and newcomer John Moore adding expert mandolin, guitar and vocals. Individually these artists are masters at their respective instruments, collectively they are ambassadors of a traditional music form throughout the country and around the world. Their music begins with the roots of country and bluegrass and expands on those traditions to create an original sound. In a discussion with all five members of California, here’s what we learned.

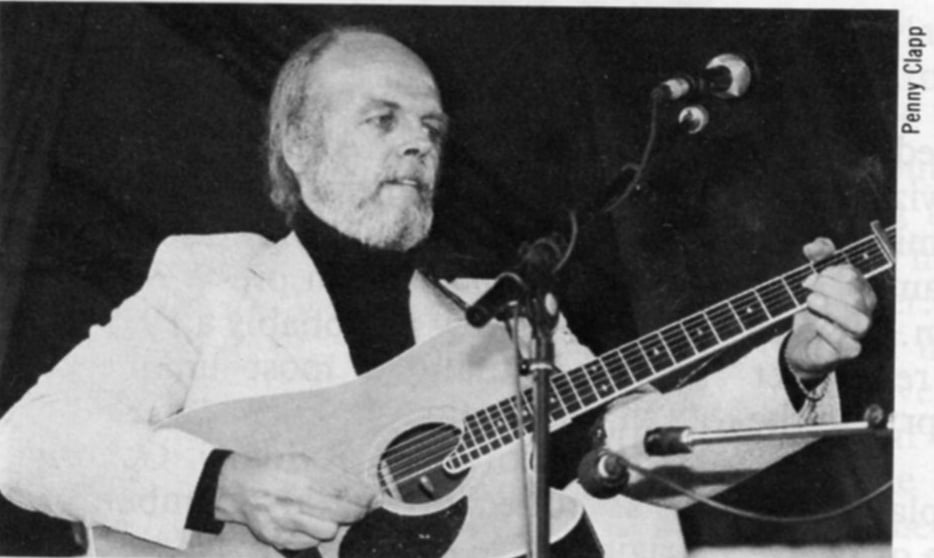

BYRON BERLINE

Byron was born in Caldwell, Kans., which is right on the Oklahoma/Kansas line. “My dad was a farmer/rancher in Oklahoma,” Byron said, “and although we lived there, our address was Caldwell, Kans. My dad was fifty years old when I was born—he was born in 1894, so he grew up in a time when fiddling was very important to the folks who lived in the farming community. He played fiddle at the barn dances and things like that. The tunes he played were definitely country tunes and dance-type, old-time fiddle tunes such as square dances, jigs, reels, polkas, schottisches and waltzes. So, that’s what I grew up playing and listening to.”

All the members of Byron’s family played instruments, but not the fiddle. “There were five of us in our family. No one played the fiddle like my dad wanted. But then I came along—the last of five kids in the family—and for some reason I picked it up and started playing it. I learned my first tune when I was five years old. Whenever anybody would come up to the house, I’d get the fiddle out and start playing for them.

“At that time, my dad started taking me to the fiddle contest that had started around the country. That was a good outlet for people because there weren’t any bluegrass or any country music festivals that I can remember at all. Swing music, of course, was popular because of Bob Wills, but I never did get into swing music then. I used to listen to it, but never played it as much.” When Byron was sixteen his dad took him to a fiddle contest in Texas and there were a lot of the great fiddle players there like Benny Thomasson, Major Franklin and the Solomon Brothers. “I learned a lot from them just by listening,” shares Byron. “I developed my own style just by listening to them … and to my dad.”

Basically, it appears that old-time fiddle tunes comprised most of Byron’s background and of course, his dad was the main influence in his life. But Byron tells us, “Besides my dad, as I started going to the fiddle contests, the Texas fiddlers influenced me a lot.

“I went to college at Oklahoma University in the mid ’60s,” said Byron. “Folk music was very big at the time and bluegrass was included in that genre. That’s when I met a group known as the Dillards. They had just moved to southern California and were doing great here playing bluegrass. They came up through Oklahoma and played a show at the University I attended on the same day President Kennedy was killed—that was the day I met the Dillards.”

The Dillards then asked Byron to do an album with them the following summer [1964], That’s what really got his career started!

Byron later worked with Bill Monroe. “I worked with him before I went into the Army but in the short time I was with Bill Monroe I learned so much because, actually, bluegrass really wasn’t all that popular. You see, in the ’60s bluegrass was accepted more in country music, since Flatt & Scruggs had hits on the country charts. But in the ’60s in Oklahoma, Texas, Illinois, etc., bluegrass was not heard of. Now it’s enjoying audiences all over the world. There’s a bluegrass band in almost every town and I’m real proud to be a part of it.

“I came to SoCal in 1969,” he shares “and played a lot with Doug Dillard . . . with Dillard & Clark, to be exact. Gene Clark (of the Byrds) and Doug had the band and I joined them when I first came here. After Clark left, I stayed with Dillard for a couple years and we did several things with Kay Starr. And we recorded one song on the Vanishing Point album for the movie.

“After that I formed a group called Country Gazette, which is still going. Alan Munde still has that band, which has been around over twenty years now. I left that band in ’75 and formed a group called Sundance. That’s when Dan Crary and John Hickman came into the picture.” But there was someone else who was in the picture then too—Vince Gill. I brought him out here in ’77 when he was nineteen.”

By now Byron Berline has had several bands. His L.A. Fiddle Band came along later too. Byron says, “We had fun with that band—but it wasn’t the ‘tour-the-world’ type band. Basically, it was for fiddle players to get together and do twin-fiddle parts.

“I came close to working with Bill Monroe when I got out of the army, but I came to California instead because Doug Dillard called me and wanted me to come here. I was here four days and we had a movie score and a bunch of other things and I thought, boy, this is the place to be.”

DAN CRARY

Dan was born in 1939 in Wyandotte County, Kans., just outside Kansas City. “We lived a quiet life,” says the musician, “Until music and other things took me away from there. I lived most of my young life in Kansas.”

Like most kids, Dan’s first experience with a musical instrument was with piano lessons. “I did okay at them, but as soon as I could quit, I did, because I didn’t like it much. So, the first instrument that I discovered for myself was the guitar. When I was ten or eleven years old I started listening to country music radio stations and discovered bluegrass. I was very taken with bluegrass music.”

But for a man whose destiny would lead him to become one of the world’s finest flatpickers, I wondered what circumstance would turn his life around.

“In 1952 I was dialing around the country music stations and found a live country music show with a guy who played acoustic guitar. His name was Don Sullivan—and I loved the sound of his instrument. At the time, I didn’t even know it was a guitar, but I knew I liked it. In those days, you see, very few people played the guitar. Of course, there were blues players and pop music players and a few great jazz guitarists, but outside of jazz, blues and country music you just didn’t hear a guitar. Pre-Elvis, the guitar was a sort of exotic instrument which you didn’t see much of.

“So, when I heard Don Sullivan play that rhythm guitar, I loved the sound of it . . . that’s what got me. At the time I didn’t have any intention of becoming a performer or anything like that, but I loved the sound of that instrument.

“At age twelve, I talked my folks into buying me a guitar. In fact, it was just about forty years ago today that I started playing.

“Flatpicking is a whole other approach to the guitar. The term ‘flatpicking’ is a sort of country expression for playing the round-hole, flattop, steel-string guitar with a plectrum. The old boys in country didn’t like the sound of the word ‘plectrum,’ so they called it ‘flatpick.’ It’s the plain old pick and it’s the plain old guitar but it’s more: Taking the large-bodied steel-string guitar, which used to be just a rhythm instrument and playing a combination of rhythm and lead music. That’s what flatpicking is. It’s a relatively new development in bluegrass music.

“The original bands only used the guitar as a rhythm instrument and it was not until the 1950s, that some early heroes like Don Reno and later on the Stanley Brothers, featured flatpickers like George Shuffler.

“Then, in the 60s, along came Doc Watson, who was not a bluegrass player per se, but can certainly play some mean bluegrass when he has the opportunity. He and his son Merle played flatpicking guitar most and became international heroes of traditional music. They, plus Clarence White out of California, set the tone for flatpicking music.”

When Dan joined his first bluegrass band, flatpicking was not being done in the music. “At that time,” says Dan, “to my knowledge, there was little or none of it. Larry Sparks was playing some, but at the festivals we played, we were the band that featured lead guitar. So, we got a lot of attention. It was totally different and unexpected to the audience. But after the late ’60s, it started to become a very ordinary thing to have the flatpicking guitar in a bluegrass band.

“The first contact I had with Byron Berline was through records,” said Dan. “Byron had done records with Bill Monroe and had done the classic ‘Pickin’ & Fiddlin’ with the Dillards and so I certainly knew of his work. And today I’m still amazed and astounded at Byron’s playing. Of course, I didn’t know until later that a record that I made in the spring of 1970 called “Bluegrass Guitar,” which was my first solo album, was something Byron listened to and his dad also liked it. They listened to my music and I listened to his!

“But our paths first crossed in the spring of ’74 when we were both booked at a bluegrass festival in Canada. We shook hands and visited and picked a little bit. That happened to be while I was finishing up my graduate work and was going to start my university job (I teach at Cal State University in Fullerton).

“Pursuing my academic work brought me to within about 45 miles down the freeway to where Byron lives. So, we got together at his place. It was about the time when Byron left the Country Gazette. We started talking about forming a band, which we did. We called it Byron Berline and Sundance . . . that’s where Byron, John [Hickman] and I first got together.

“California is sort of a dream band for me, because the people in this band see very much eye-to-eye. Byron and John and I have worked together for a very long time and what we do works together. I’d be quite happy if this was the last band I ever played in. If I worked in this band for the next thirty or forty years I’d be quite happy to do that. Steve’s writing gets better and better all the time and the addition of John Moore to the band gives it a wonderful new dimension. They’re all good guys . . . they’re people that I like to be around.”

But why did the group choose to name the bluegrass band, California? “Now, the very fact that you asked me why we call our band California is in itself the answer, in a way. If you wonder about it, then you’re paying attention—and we want people to pay attention to our new format and to give a listen to the music.”

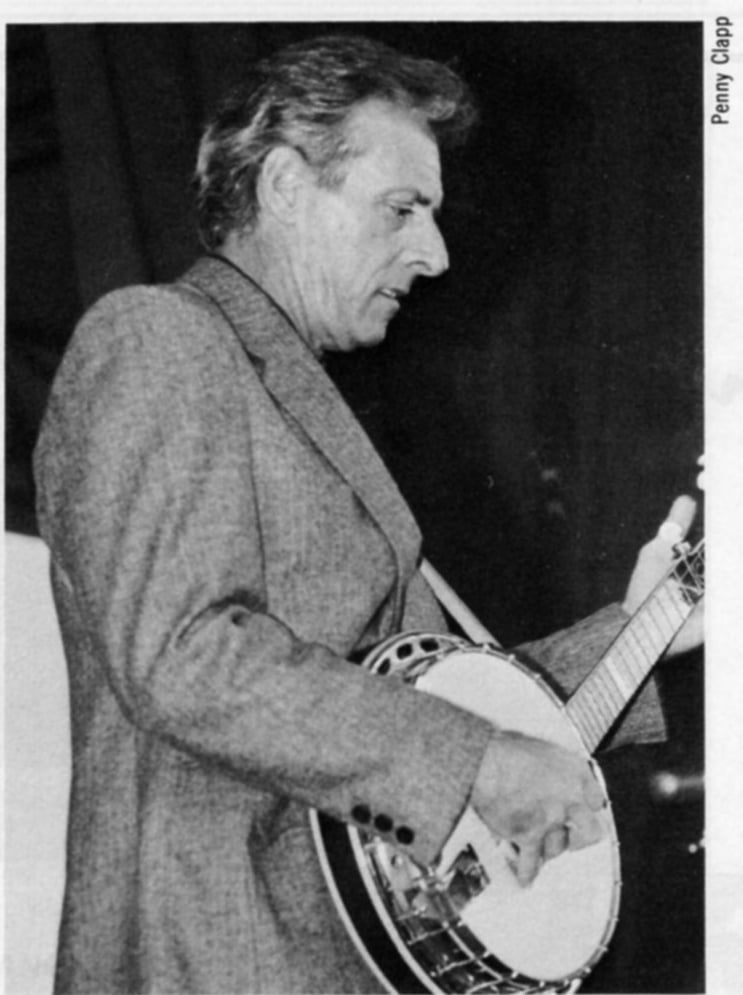

JOHN HICKMAN

John was born and raised in Columbus, Ohio. This banjo wizard did not come from a musical family. “No one on either side of the family ever played anything,” said John. “I was interested in it and I could remember listening to the Grand Ole Opry, so the interest was always there.

“The first instrument I played was a guitar. At about age eleven or twelve I was looking around to find somebody who played so I could learn something and play along. Well, there was this guy named Burly Blankenship who had some 78 r.p.m. Flatt and Scruggs records. He’d sit around and play his guitar and people would stop by and play along.

“The first time I went over there Burly showed me a few chords on the guitar. But suddenly my interest just made a big move toward banjo. I think probably because Elmer Burchett showed up over at Burly’s one day and that really generated some interest in the banjo. (Elmer played banjo with the Bluegrass Playboys, as I recall.) And, of course, all those wonderful Flatt and Scruggs records turned me around,too!

“Burly had a banjo,” says John, “and I wanted it. So I traded my guitar for the banjo. I remember I’d bang on that thing for sometimes ten hours a day so that I could learn it. There was nobody teachin’ it, so everytime I’d go over to Burly’s I tried to watch him and learn from him. Consequently, it took quite a while to learn what to do with the right hand, which, in my opinion, is about 75% of what bluegrass banjo playin’ is all about . . . it’s all in the right hand.”

John Hickman mastered the art of playing the banjo. And he’d had a collection of instruments, too. “I’ve had over thirty of the old Mastertones,” he says. “By old I mean pre-WWII. The one I have now is probably a 1931-1934 and is actually a most unique and desirable banjo.

“According to Sonny Osborne, he’s collected serial numbers of original five-strings and he’s figured there’s probably less than 100 in existence today. Mine is one of the original five-strings and it’s the first one I’ve managed to get.

“I came to California late in ’69 and one of the first musicians I met was Scott Hambly, a mandolin player. Then my younger brother came out and he’s a good guitar and excellent bass player. So, my brother George, Scott and I got together and got booked at McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica opposite Doc Watson. So, we were billed as the Hickman Brothers & Scott Hambly.

“Meantime, Byron and Alan Munde decided to come down and find out just who the characters were at McCabe’s. I met Byron there and he invited me over for a jam. By 1975, after he stopped playing with Country Gazette, he started Sundance. Byron, Dan Crary and myself had done some instrumental albums and they generated interest in Japan, so a tour was put together.

“By the end of our tour, we figured, ‘Well this isn’t too awful bad, maybe we’ll see if we can’t keep it up.’ We did keep it going for a long time, then we added Steve and now John.

“We spent a long time trying to figure out what we should call the new group. I feel it doesn’t matter as long as the audience is able to connect to who’s in the group, what the group does and the name. Our sound is different. We are California!”

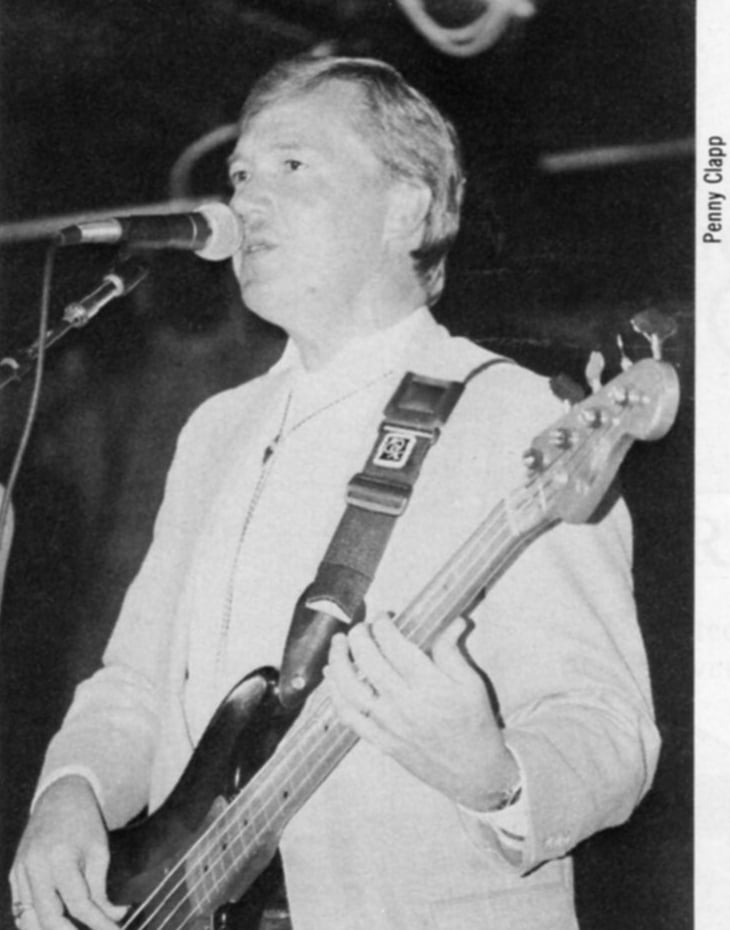

STEVE SPURGIN

Born and raised in McKinney, Tex., which is about thirty miles north of Dallas, Steve tells us his family wasn’t very musical, either, “Except for my brother David,” Steve said. “He was in school bands and I started taking piano lessons when I was five. My mom figured it was time for me to start lessons because I was picking up tunes by ear. I took lessons for eight years, but I quit when I was thirteen because I’d rather be out playing baseball.

“I also sang in church and school choirs and played in the band. I never thought about songwriting then. The first song I wrote was in ’67 and, it happened so fast, I wrote it in fifteen minutes. It was a pretty good tune. I didn’t try to seriously write anything until 1980.

“Some people are natural writers . . . I’m not sure I’m a natural writer. A lot of people who write seem to have an easier time of it than I do. It comes in spurts with me. I can’t sit down and force myself to write.”

But Steve wrote a couple of smash hits for Gene Watson. “When I wrote ‘Speak Softly, You’re Talking To My Heart’ and ‘Carmen,’ I was with Sundance and we opened a show for Watson in L.A. Neither he nor us was supposed to be there. Gary Stewart was supposed to do the show but he broke his arm and couldn’t do it, so they got us. It was a fluke that Gene recorded ‘Speak Softly.’

“Anyway, I had a demo tape that I gave to Gene’s drummer and a few weeks later they called me and said, ‘I hope you don’t mind, but we cut one of your songs.’ And that was ‘Speak Softly.’

“Then I signed to his publishing company for a couple years and after that I was signed to Reba McEntire’s publishing company for a year. I now have my own publishing company.”

Steve pulled a real switcheroo when it comes to musical instruments. He’s an accomplished pianist and drummer, so why is he now playing bass guitar? “For years I was a drummer, but now I’m pickin’. I played guitar during the ’60s and got away from the piano, trumpet and French horn. I started playing guitar during the folk days. I think the person who first influenced me to play guitar was Bob Dylan. He was so unique, that I wanted to learn guitar so 1 could play some of his songs. I had a classical background, but then I also grew up listening to the Osborne Brothers, the Wilburn Brothers and Porter Wagoner. I had all those different types of influence.”

Steve was into folk music back in Texas in ’67 playing acoustic guitar. Then he came to L.A. “In 1969 I moved here and started to play drums with a folk group and we became sort of a top-40 club band. I got elected to play drums, which I played for almost fifteen years.

“Byron and I were introduced by Patty Burrows. When she heard that Byron was looking for a drummer, she told him about me. In ’73-76 I was playing drums in an electric bluegrass band called Wild Oats. Everything was plugged in and they played through amps. They were ahead of their time, to say the least. That band was an offshoot of Aunt Dinah’s Quilting Party, which used to work on the old Andy Williams show off and on, then they turned into the electric bluegrass group called Wild Oats.

“Now we have California. You know, we run into this a lot, that you can’t do bluegrass unless you happen to be from Virginia or Kentucky. There’s nothing wrong with somebody doing bluegrass music outside of the ‘heartland’ of bluegrass music. Some people think that unless you’re from there or live there, you’re not really a bluegrass musician. But there’s been some incredible bluegrass bands that have come out of the West Coast. Right now, probably one of the most well-thought-of bluegrass bands goin’ is the Nashville Bluegrass Band and three of their members have California connections.

“When we were thinking of a name for the band, the idea came up . . . since everybody considers us a West Coast band anyway, why don’t we just go ahead and run with the whole idea and take it all the way and just call ourselves California and live or die with it. Because we are a bluegrass-oriented band. I think we put on a heck of a show, but people need to see us—then decide for themselves.”

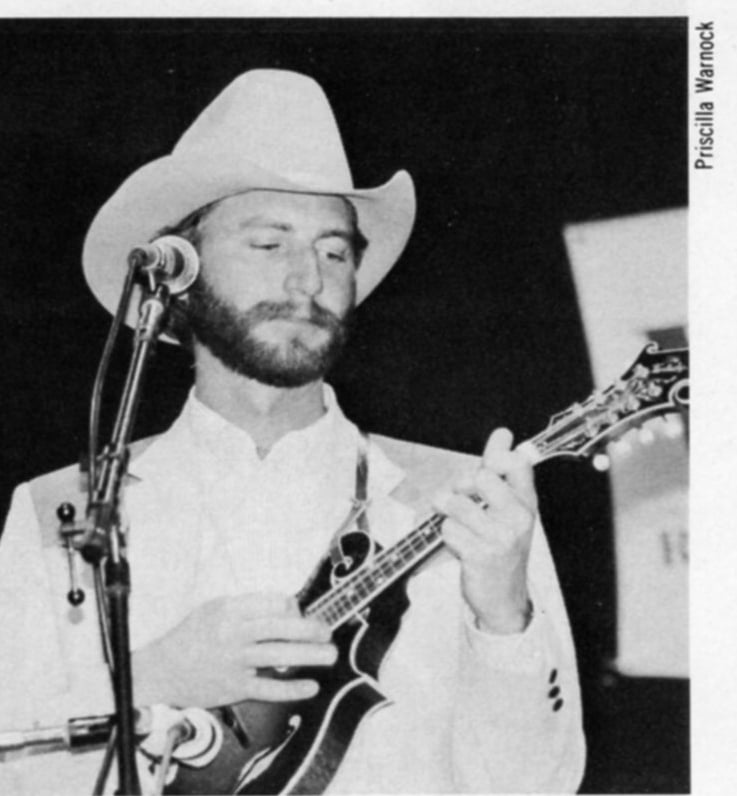

JOHN MOORE

John is the only true native Californian [Oceanside] and makes his home on Palomar Mtn., Cal. Oddly enough, his first instrument was a ukelele his parents bought him from a garage sale for fifty cents! “I learned to play it, too,” says John. “Then when I turned nine my folks bought me a mandolin. I think they got me a mandolin because my mom wanted to learn to play it.

“I’ve never taken lessons on the mandolin or on any instruments, but I had some Homer and Jethro, Sons Of The Pioneers and Ernest Tubb albums that I’d play along to. But I guess you can say that Jethro Bums and Bill Monroe were my two biggest influences.

“Meanwhile, Stuart Duncan and his family lived across town (they had a group called the Pendleton Pickers). A mutual friend told the Duncans about me and they wanted to add me to their family, so I joined them.

“After the band broke up my sister and I went out as a duo for awhile, then added a banjo player named Dennis Caplinger, who’s an incredible banjo player. We had a trio and were playing in Hugo, Okla., when I met Byron Berline.

“But I had actually met Byron several years earlier at the Norco, Cal., festival, but it wasn’t until after we re-met at Hugo that we began to pick together. I joined this band almost two years ago and it was kind of like working myself into it . . . more so, in the past year. But I’ve noticed, since we’ve started recording this new album, there’s been some style changes starting to happen, which is neat. The evolution of the band, I think, was slowed up a little because we were so long in getting into the studio. Recording sometimes causes you to try new things. So, it’s going down a different pattern than any of the other albums have gone. Everybody’s exploring some new styles and I brought in some songs and Steve has written some new songs and all this helped create the mood for our debut album. This will be a different-sounding bluegrass record, because every member’s influence can be heard.

“Sometimes you can get into a rut playing certain licks, certain speeds, or certain music, so you have to branch out and challenge one another.

“We’re doing some songs on the new album like they’ve never been done before, so the guys are starting to explore a little bit. I’m starting to explore a little bit. It’s been good for all of us.”

Alice Nichols makes her home in southern California. She has been a staff journalist with the COUNTRY & WESTERN VARIETY in Hendersonville, Tenn., for 2 1/2 years. She also was editor of the WEST COAST COUNTRY MUSIC REPORTER for 2 years