Home > Articles > The Archives > The Osborne Brothers—From Rocky Top to Muddy Bottom

The Osborne Brothers—From Rocky Top to Muddy Bottom

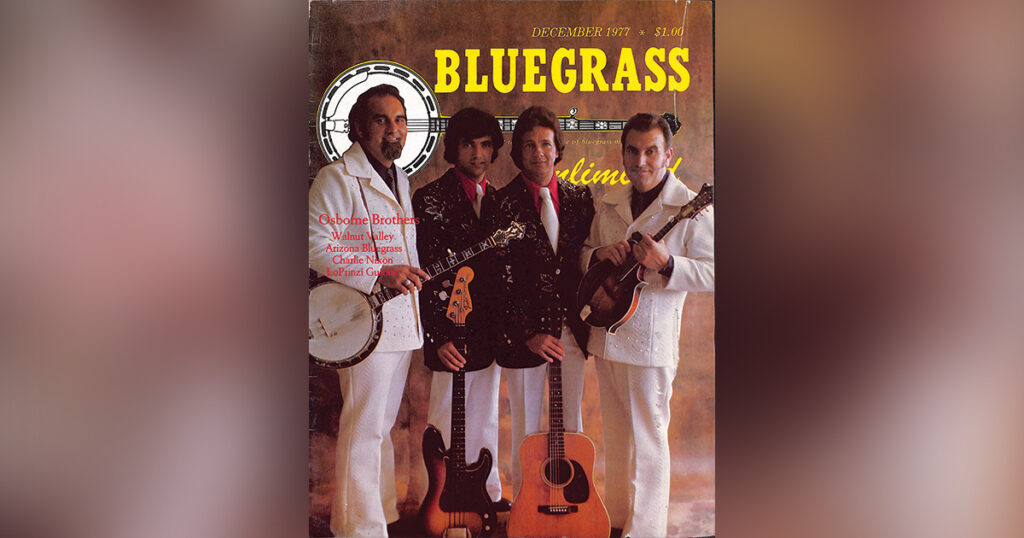

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

December 1977, Volume 12, Number 6

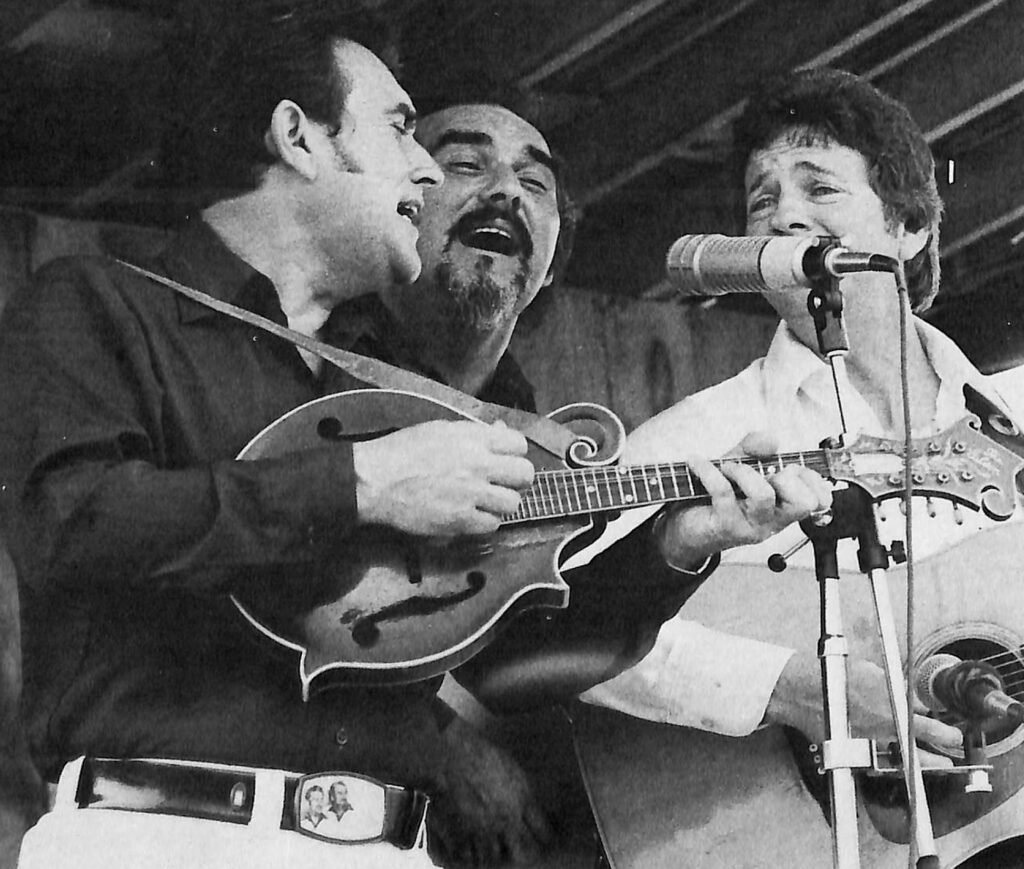

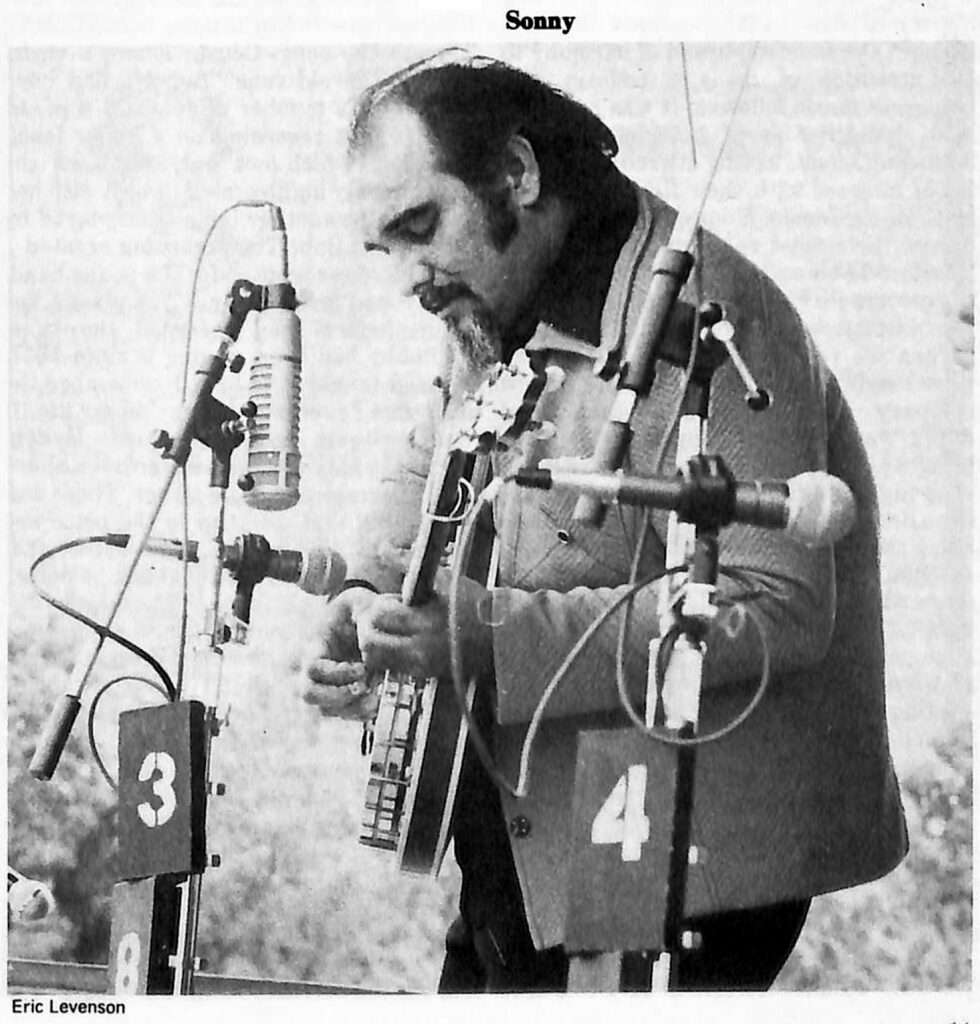

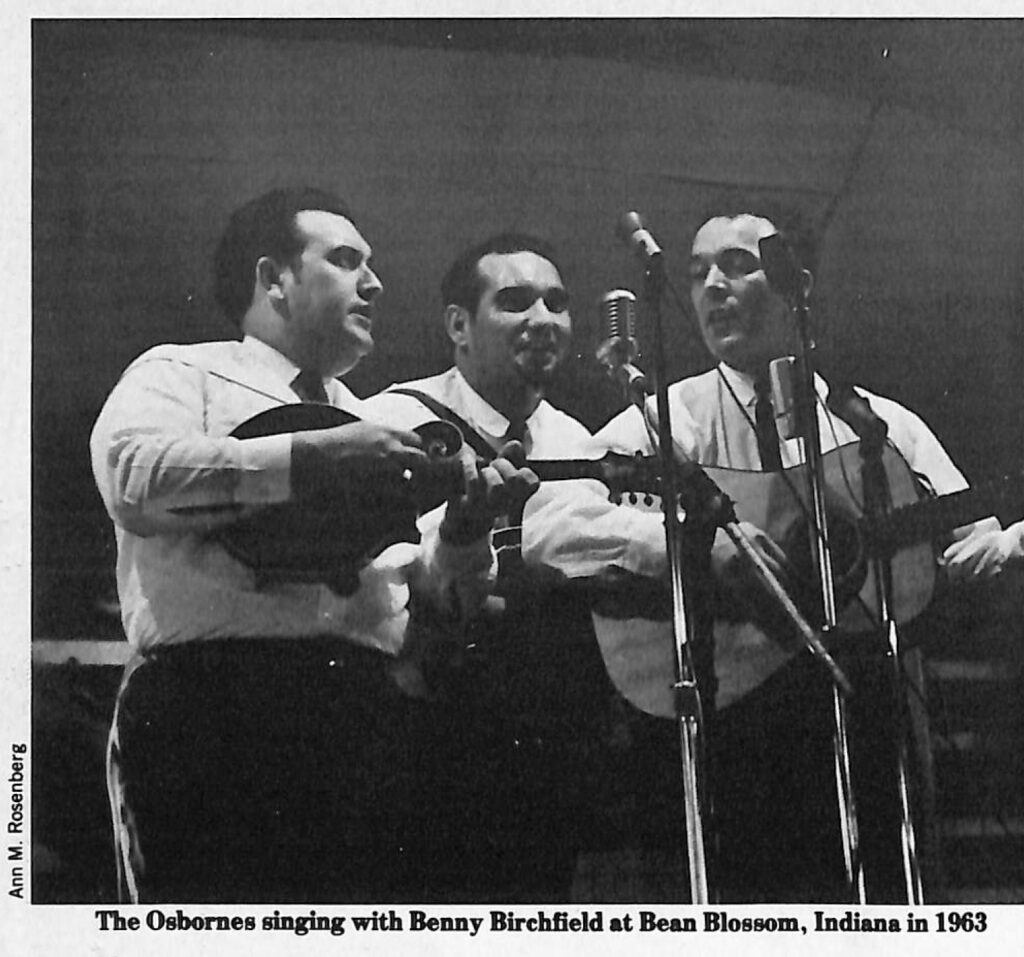

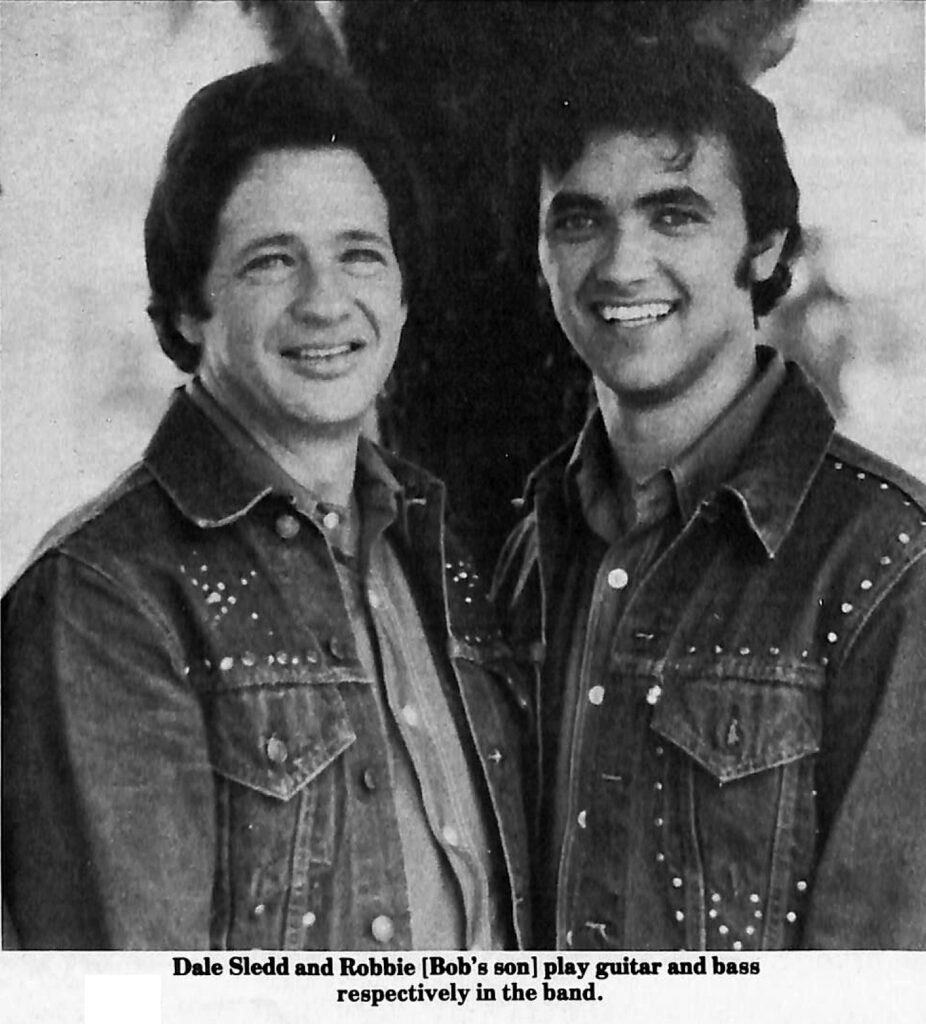

Alot of things have transpired with the Osborne Brothers and their innovations and contributions to bluegrass music. While they have been the subject of many comments about going electric, adding drums, and basically experimenting within the general framework of the music, Sonny and Bobby, along with their current band members Dale Sledd on guitar and Bobby’s son Robbie on bass, have always been in the forefront of the industry. Their superb vocals and unique instrumental breaks have had some of the most profound influence on the directions that the music has taken. Recently Sonny, the group’s off-stage spokesman, talked at length of their accomplishments and musical goals.

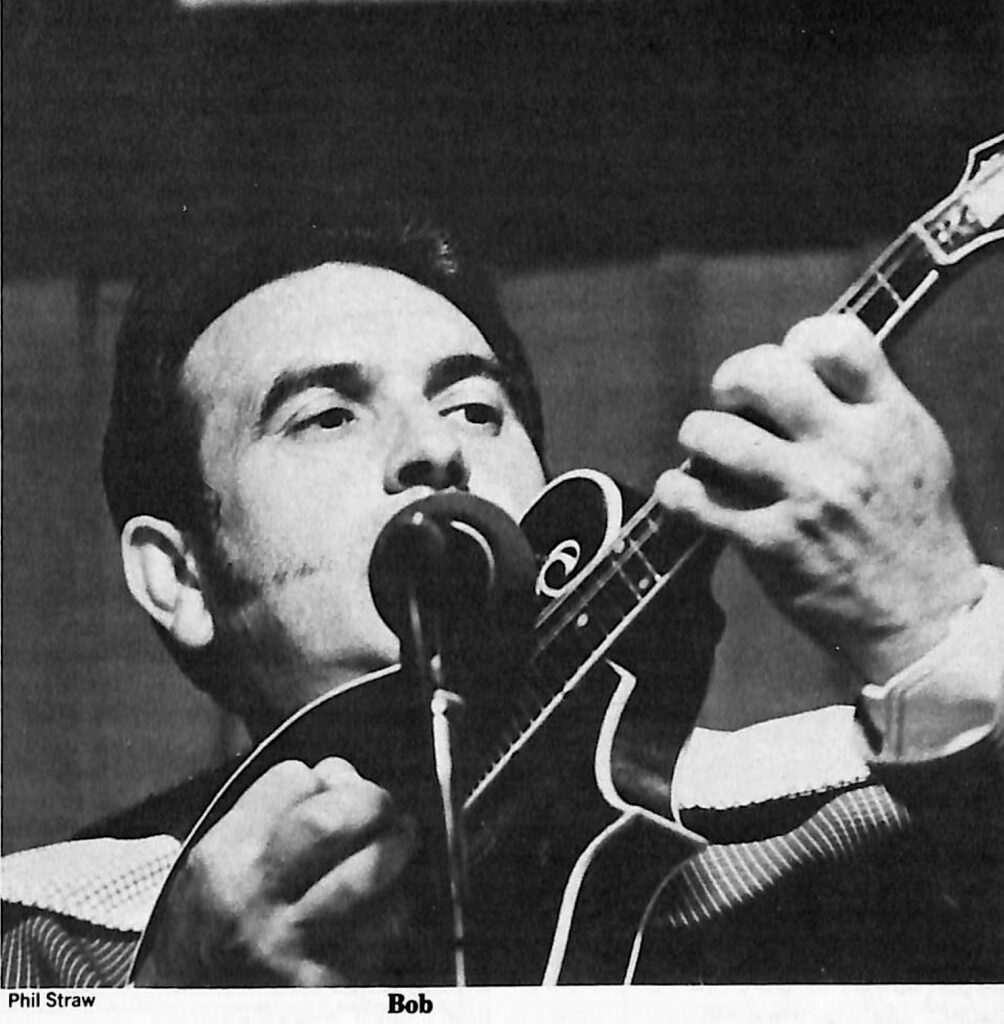

One of the changes that The Osborne Brothers brought to the vocals in bluegrass was their use of the high lead (done by Bobby) as the melody line with the other two harmony parts (within a trio) being below the lead vocal. This was completely new for most all of country singing and especially in bluegrass. The trio had been done for years with the normal melody, then a tenor harmony part above it and the baritone below the lead. Though groups had added the third part above the tenor harmony line, usually referred to as high baritone. Sonny and Bobby were the first to put the highest part as the melody and put the others below it. This innovation has gone on to be taken up by almost all of the bluegrass bands to have come along since the late fifties. It gave the flexibility to get a wider range of vocal arrangements and put songs in a key conducive to the best sounds from the instruments used in bluegrass. In the case of Bob and Sonny it was done as a matter of convenience to make the utmost use of Bobby’s one-of-a- kind voice.

Sonny explains their change as one that was carefully engineered. “It was by design. It really was. ‘Once More’ was the first song we got that lended itself well to that style. Bobby was actually forced into singing verses of songs and his voice was not down in what we might call a Lester Flatt register. It was too high. We would always have to put songs in high keys that were outrageous so that Bobby could sing the lead to them on the verses. Then when Red (Allen) or I would try to sing the lead in that key it was just so high and he (Bobby) was singing tenor to that. We just got to the point where we would just raise it on up another step or two, past those keys, to where he would be really comfortable and sing lead to it right there and we could sing the two other harmony parts under it. The part that Red Allen was singing in the beginning was a low tenor. We have kept that same approach, even to this day, on most all of our vocals. If you would take what Red was singing in those days on things like ‘Once More’ and put it above what Bobby was doing, you would have a normal trio. We just moved the part down to the lower register and it worked out pretty good.”

“Once More” was the first in a long history of slow ballad numbers that has brought the Osborne brand of harmony to the attention of many a country and bluegrass music follower. It was not their first noticeable bit of notoriety on the recording scene, having stirred up quite a bit of interest with their first release on M-G-M of Cousin Emmy’s “Ruby”, still one of their most requested numbers to this day. Their cutting of “Once More” and the change that it made in their sound was not without opposition along the way. “When we recorded it, M-G-M, Wesley Rose and Jim Vinneau (their record company and producers at that time) didn’t want us to do anything like that because we had been successful with the real high, up-tempo things that hadn’t been done before in the way that we were doing them. Songs like ‘Ruby’, ‘Ho Honey, Ho’ and ‘Della Mae’ and things like that were what people associated with us. But let’s face it, when you do three of those type songs, you run out of material fast and we knew that. So we started really looking for other types of songs. We heard Dusty Owens sing ‘Once More’. I remember one Saturday night on the way back to Dayton, Ohio, after we were at the Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia, we worked it out completely right there in the car. We sung that song all the way back to Dayton and decided that the next time we would go back to cut, we would lay that one on them. We were just jumping up and down over it. I felt sure that it would be a success. Of course, I didn’t know what a hit was.”

The one song that did more at that time to showcase Bobby’s voice was “Ruby”. Though the song—Cousin Emmy’s variation on the old tune “Ruben”—had been around for a number of years, it was the group’s first recording on a major label. The cut, which not only featured the uncommonly high vocal of Bobby, also had twin banjos-another innovation-played by Sonny and Bob. The recording created a good bit of recognition for the young band. Bobby had been doing it for almost ten years before they recorded the tune.

“Bobby had been singing it since 1947. My dad taught it to him. I remember the first time I ever heard ‘Ruby’ in my life. It was in our home town of Hyden, Kentucky. My mother’s sister lived above a Ford garage on a little street. There was a little hill that went up to the place and there was a little dive right beside that street. They had an old jukebox in there—one of those old nickel type deals—and they would have the doors open since there was no air-conditioning, and Cousin Emmy’s record of ‘Ruby’ was on there and you could hear it—the way she played the banjo. They played that record all night long. I remember it was a real big record back then. That must have been ‘45 or ‘46. Bobby started singing in ‘47 or ‘48 and my dad taught him that song. He was singing more like Ernest Tubb at that time. He really liked Ernest Tubb and could play the electric guitar and pick the breaks like were on Tubb’s records and sing Ernest’s songs. We were listening to the Opry then and he heard (Earl) Scruggs play the banjo with Bill Monroe there and it just set his head up. It just messed him up completely and he wanted to sing like that. That’s when daddy taught him ‘Ruby’ and he sung that on WPFB radio station in Middletown, Ohio. (The family had moved to Ohio, as many Kentuckians had done, during the forties.) There was something like eighteen telegrams that came in from people who had heard him do it and it was the most popular song in that whole area.”

Radio station WPFB in Middletown, Ohio, since it went on the air in 1947, has been a strong force in the preservation of traditional country music. With its current leading spokesman for bluegrass and country music, Paul (Moon) Mullins (see BU December 1975), the station was where both Sonny and Bob received their first exposure as entertainers.

“There was a guy named Ranny or Randy Dailey there. I guess it was Randy Dailey. He was the honcho up there. I guess he would be called the program director now, I don’t remember what he was called then. They had this radio station out on a farm in the old farmhouse and they put up a great big tent right outdoors, right beside the farmhouse in a field. They had this jamboree on Saturday nights. We only lived eighteen miles from there and it was the first place I ever played when I was a kid. I made $4.00. I think that Bobby made $2.00 or maybe it was $3.00. I remember I beat him by a dollar. My sister (Louise) played guitar with us sometimes then. She didn’t do it all the time. She never played with me and Bobby a great deal. She and I played together a little bit when I first started playing. Bobby was playing in West Virginia (with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers) at the time. He and Jimmy Martin got together when Bobby was in West Virginia and when Bob went in the service, Jimmy moved up to Ohio. Me and Jimmy started playing together a little. Jimmy had a full-time job and I was going to school and couldn’t play much. Then Jimmy went back to work with Bill Monroe. Those were the good old days when times were bad.”

The music that they were playing during those early years was not necessarily bluegrass though the influence of Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs and the many other early greats was making its mark on the Osborne Brothers. “There was no such thing at that time as bluegrass. If you played the guitar or banjo and sung that type of thing, it was hillbilly music. You was a hillbilly. Bluegrass had never been heard of. What they now have put into a little box and called bluegrass, started all of country music. In the very beginning a fiddle and a banjo is what started it all. My daddy used to do some of it. He would go out and play at some of the dances on Saturday nights, when people didn’t have television or movies or anything like that to go to, and there would be a fiddle and a banjo and the pickers would go out and play for those things all night long. In a church, or a school, just anywhere people could get together. Then they started adding all this other stuff and they called it country and we had to take some other name. What we do is really country music. It’s the soul of country music and this nation.”

This objection, to being cast aside by the mainstream of the country music industry, was the principal reason that the Osborne Brothers made a number of moves within their musical structure and recordings to bring their music to what has become two distinct elements of string music-bluegrass and country. It was the changes during the gradual evolution of the two styles that Sonny feels hurt the market that they were trying to get their brand of music to.

“That was when they separated the beginning from what it is now. That was what me and Bobby worked so hard to do in the sixties—get that point back together. For us, it succeeded and if it had been left alone like that I can just imagine now how big the whole concept of music—of country music—would have been if they had left it all in one piece. When they split something up, neither of them are going to be able to do that well. We tried to put that point back together. We did a con-job on the country music radio stations to get our records played. Country disc jockeys, at that time, were usually people who had little experience in country music. Country music was getting so big and these people were forced into this job that they had never done before. The most outstanding instrument on a country record was a steel guitar. The fastest way to get a record played on a country station or through a program director that didn’t know anything about country music was to give the D-J something he could identify with. Then the program director could say, ‘Oh yeah, that’s country music. You can play that’. So we put a steel and a piano and all that stuff on our records. We never did lay our instruments aside—we had the mandolin, banjo and all our regular sound plus what we added to get the records played. And it worked.”

The lack of radio play for their records, as well as the other more traditional country and bluegrass acts, is a sore spot with Sonny. Even though the Osborne Brothers were one of the few groups lucky enough to get their records played on a number of radio stations, Sonny felt the pressures of the division between bluegrass and country. “I can understand thoroughly the feelings of black people and Indians and any minority group now. I’m for them 100% because we’re in the same boat by being bluegrass pickers. You’re looked down upon by these disc jockeys, if you want to call them that. I think they are more like robots. I got into a tremendous argument with a guy from WJJD in Chicago one time. We played a club in downtown Chicago and did three shows and there was standing room only for every show. This D-J was there and we did an interview for the station and he said, ‘I don’t understand, we’re not allowed to play bluegrass records on our station but you guys got three standing room only crowds in downtown Chicago.’ There was a snowstorm on top of that. I told him the only way I would allow him to play this interview was to let me ask him one question with the tape recorder still running. I asked him, ‘You listen to all the commercials on television and on radio and just about 99% of them have got a banjo and some sort of bluegrass instruments playing behind them and singing along with it too and this sells products. Then why in the hell don’t you let us try to sell our music on the radio station by playing it?’ He sat there and thought and finally said, ‘Well, I can’t answer that. I don’t know. I’m not the boss.’ That stopped the interview. We’ve fought so hard to get our music around and I’ve argued and I’ve been called every name in the book.”

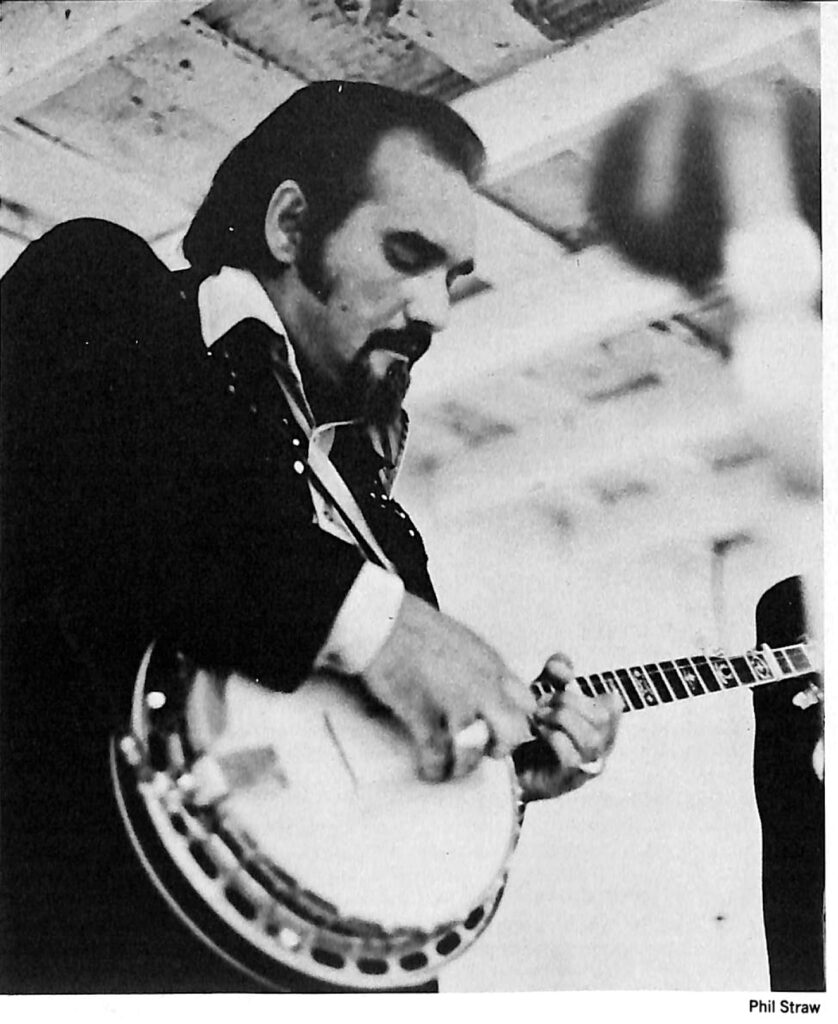

In trying to carve out a place for their brand of music in the very competitive world of music, they realized that they would have to come up with something that was their own. As Sonny puts it, “I realized in 1957 that I couldn’t copy (Earl) Scruggs anymore because, when he was through and couldn’t play anymore, that I’d still have some time left. Then I couldn’t play anymore either. So I started going out and I’d listen to anything there was to listen to. A piano, a horn, anything, and then I’d go and try to put that note on the banjo. And we changed our singing around too in 1957. We’ve always had the singing thing because of Bobby’s voice. There isn’t another voice like it in the world. I still think that way. I’ve stood beside him a lot of years and no one else can quite do what he can do. No one ever will either. The singing we had and we knew we had to do something so the disc jockeys would play it. It all boils down to material. That’s when we started to do a lot of different things like, “Up This Hill and Down” and “The Kind of Woman I Got” and the pretty ballads and things like that. Son-of-a-gun, they started playing our records.” They also were starting to get booked on the big country package shows mostly produced by Carlton Haney through the south. “Carlton Haney had started that. I think the guy deserves more credit then he’s ever got. He did an awfully lot to get (Don) Reno and (Red) Smiley on the map when they were working out of Roanoke, Virginia and he helped us a lot in the early years. I remember that we always could get a date from him when we needed it. He was one who always would help. Back then it was rough to get enough shows to make it. We were playing a tour in Canada and we didn’t even have enough money to get home to Dayton on. We were supposed to play this club or hall, and we had been advertising it on Wheeling, and when we got to the place there wasn’t anybody to man the door or anything. I remember climbing up through a window in back of the club and opening the doors and we stood there and sold tickets. When we got enough people in, we went on and played the show and then went back out the window with enough money to get home. Anyway the bad things that Carlton has done have been publicized and none of the good things get much attention. I remember, it must have been 1959 or so and we had just played a show in Luray, Virginia and we were up eating dinner on top of this mountain outside Luray with Carlton and he said, ‘One of these days I’m going to get all these bluegrass people together for one big show that will last the whole weekend.’ We laughed at him. I said you’ll never get them all together. They’ll be fighting and carrying on. ‘Nope,’ he said, ‘you watch. One of these days I’ll get it all together.’ And he did.”

The country package show was a big staple in the appearance schedule of the Osborne Brothers during the early sixties. It also was one of the primary reasons for going electric. “We were getting hot in areas where Carlton was producing these shows. Places like: Greenville, South Carolina; Knoxville, Tennessee; Greensboro, Raleigh and Asheville, North Carolina—and he booked us on those things. For the first two or three we went out and would be following someone like Dottie West or maybe Conway Twitty and people like that—they were great musicians, but extremely loud—and we would follow these people on. There would be maybe 9,000 people sitting out there and we’d sound about two inches wide compared to those amps and all. After about two major flops we knew that we had to do something if we were going to do this type of thing and this was exactly what we wanted to do. We wanted to put them both in the same light—country and bluegrass music—and pick up that huge country audience and sell more records, thus making more money—that’s what it’s all about. So we started working with amps. It took a while and it took a lot of money and a lot of other things we didn’t have at that time or didn’t know about. But we knew we had to do something so we came up with the set-up we had. I still think it had a hell of a sound to it. We added drums and we got an almost-rock bass player, Dennis Digby, we could sing country songs on top of that and we went out and put on a show for them.”

“In Greenville, South Carolina we played one—the last package show we did—and we were on with Johnny Paycheck and he had a big hit with ‘Don’t Take Her, She’s All I Got’. He was on second or third in the show and the best place on those package shows was to close the first half. That’s the top spot, and we got to close the first half, and Johnny couldn’t understand it. He was wondering why they had put him on second. He said, ‘I never thought I’d see the day when a damn bluegrass band would be closing the first half of one of these shows.’ And I said, ‘Well, stick around John, because today you’re going to see one.’ When we came off, we got a standing ovation. It was like a 747 going over when we got through and John was standing there and I said, ‘Now you understand why we are closing it.’ He and I were good friends and I could kid with him like that. But we had proved our point.”

The country package shows started to dwindle. Groups like Porter Wagoner, had put complete shows together themselves and would come as a unit so that promoters did not have the need to book a number of artists to have a total show.

“Guys like Porter Wagoner would have his complete show, which would fill an auditorium first of all, and on top of that, it would fill up the acts that were needed. There weren’t any more parts to be taken. Another thing, too, was that many of the artists started pricing themselves right out of the business. Instead of getting $2,000 or $2,500 a day, they started asking $7 or $8,000 a day or maybe $5,000. If they could get it that’s fine. I’m all for it. It’s like a baseball player. You don’t have long in this business so you’ve got to get it while you can. But it got to the point where they weren’t drawing the people and, with asking too much money, the promoters were having to raise the gate prices too high and things started to fold.”

After the package shows left them looking for an outlet to perform, they joined with the Merle Haggard show for three or four years, doing about 95% of his dates. They also lost their guitarist at that time, Ronnie Reno, to Merle’s organization. Dale Sledd, who had been with them earlier, returned and remains to this day. Bobby’s son, Robbie, started with the group originally on drums, then switched to the electric bass completing what was an almost total family band.

They have also switched record labels joining, with a number of bluegrass and traditional country acts, the aggressive C.M.H. Records based in Los Angeles, California. Their latest LP, a double set, titled “From Rocky Top to Muddy Bottom” was conceived as a tribute to Boudleaux and Felice Bryant, who have given Bob and Sonny a large portion of their material over the years.

“Boudleaux and Felice (his wife) Bryant are the best writers in the world or at least in the top five. They are the people who really put us in high gear. When we started working on the album I got to thinking what the biggest bluegrass song has ever been. Naturally ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky’ comes to mind but it was not that big a song until (Elvis) Presley sold a bunch of records of it. That was a different situation. Of course, we’re not Presley either. Then there was ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’ which had the movie behind it. Probably the next one would have been ‘The Ballad of Jed Clampett’ and that had national television exposure behind it. Then, when you get past that, you come to ‘Rocky Top’. That has got to be the next biggest song in bluegrass music. Then there’s some more of them like ‘Tennessee Hound Dog’ and ‘Georgia Piney Woods’ that came out one after the other. (All written by Boudleaux and Felice Bryant.) I got to thinking why not have this guy write a whole album. Do twenty songs from him. So that all worked out well and that album, ‘From Rocky Top to Muddy Bottom’ has everything we can do. We got the songs, we arranged them, we called the musicians, we got the studio, got the engineer and did it all.”

The Osborne Brothers recently did a Japanese tour and came back, like all of the other bluegrass groups who have played there, impressed with the audiences in Japan. “We went to Japan and played to approximately 2,000 people a night. They were paying what amounted to $18.18 a ticket to get in. I hate flying with a purple passion but if they want us back I’d like to go back. We were almost mobbed. I’ve never seen anything like it in this country. They know everything that you are going to do and they have to learn it the hard way. They just can’t walk up and down the street and find bluegrass entertainment. They don’t know what the words mean, they have no idea. But they were beautiful crowds and I’d like to go back.”

Allied Entertainers, Inc. was another endeavor that The Osborne Brothers, along with Lester Flatt and Lester s manager, Lance Leroy, started in recent years to bolster their representation for bookings. Lester and Sonny and Bob recently parted company on a friendly basis with The Osbornes retaining the Allied Entertainers name and organization P.O. Box 647, Hendersonville, Tennessee 37075) and Lester and his manager forming a new booking agency, Lancer Agency. “It was a friendly thing. We’ve got the highest respect for Lester and Lance but just felt that maybe we could devote more time to promoting ourselves rather than have things divided. We bought out their interest in the company.”

Sonny and Bob have now returned to their roots playing mostly traditional bluegrass tunes plus the many requests from their records over the years. Though the innovations they have brought to bluegrass music have been many, they still respect the things from which the music draws its strengths. Even after doing their con-job on the country music stations, in order to have their records played, and the successes they have had, they have returned to the way of playing that they started with and seem much more at peace with their music for doing it. “We’re playing now what we want to play and doing the songs that we want to and if there was anything else I would like it might be to hire a very good fiddle player and just go into playing some old grass. When Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs had Curley Seckler and Paul Warren or Benny Martin, that’s bluegrass music exactly the way I think it should be played. I’ve got a lot of records of that vintage stuff and I listen to it religiously. It’s like a bible to me. It really is. That’s how we learned to play when we started. In Lavonia, Georgia this year, Chubby Anthony, the fine fiddler from Florida, worked some with us and I really enjoyed that. They always book us at Lavonia the week before the main festival but we still had a tremendous crowd down there this year. We had always done two shows one day and one show the next day. I sent word—we were just ready to go on stage—to have Chubby Anthony come down here with his fiddle. We did about ten minutes of requests, just one right after another, as fast as we could. I went to the mike and said, ‘We’ve done everything you’ve asked us to do and Chubby Anthony is a great fiddle player—one of the best as far as I’m concerned—and for the next twenty or thirty minutes, we’re going to do what we want to do and if you like it that’s fine, or if you don’t, you can go back up on the hill. If you want you can stay out there and enjoy it because we’re going to play some bluegrass like it came out in the fifties—and we did. We played them all and Chubby did some fine fiddle work. I’m going to do more of that type of thing. Especially next year at Lavonia. I told Roy Martin (promoter of the festival) that I wanted (Chubby) Anthony back again next year. We’re going to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina this year on Thursday and Saturday and I’m going to do the same thing there too.

“We had, in the relatively short span of eight or ten years, made more money than I had ever dreamed was in the world, first of all. And we won the country music (Country Music Association’s) ‘Vocal Group Of The Year’ award. And that was the goal right there to me. We did that. That reached the top because we proved to them that we could play their ball game and beat them at it—and we did. We were nominated in the top five country vocal groups for seven years in a row and at the same time, we were winning the number one bluegrass band of the year. We’ve won it now for eight years in a row, so we’ve proved our point. Now it’s kind of getting back to the basics of why you breathe. You go through all this stuff and start to think—how do you exist? What do you exist on and it’s air. And you breathe and you go this way and you go that way and we wanted to get back to what we are made of. That’s bluegrass pickers, if that’s what you want to call it. We’ve had a lot of fun and accomplished everything and more than we ever set out to do. We’re playing now exactly what we want to play and really enjoying ourselves.”