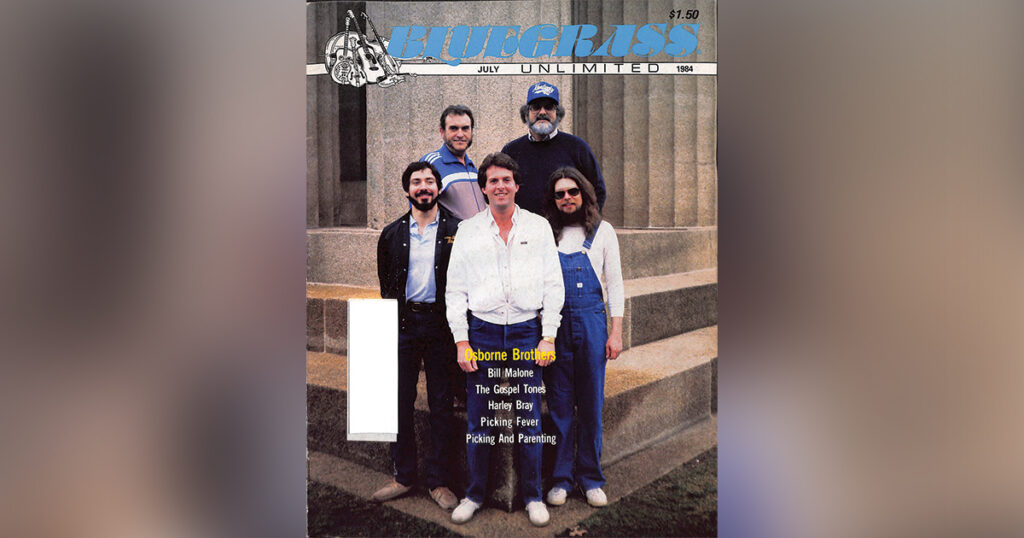

Home > Articles > The Archives > The Osborne Brothers

The Osborne Brothers

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July, 1984, Volume 19, Number 1

Bobby Osborne—Living Out The Legend, Outliving The Threat

Bobby Osborne has a dream of making a movie someday, a story about bluegrass. “Maybe my own life story,” he suggests. In many ways, the Osborne Brothers’ story is the story of bluegrass. The events in the lives of Bobby and Sonny Osborne which parallel the legend are many: born in Kentucky of a musical family, migrating to the North, being caught in the spell of the Grand Ole Opry, and finally, creating a sound, a harmony, that has etched itself in bluegrass history.

Those are the facts, facts somewhat dulled by repetition. Life is more than the sum of a string of events, however, and it is a flesh and blood struggle that makes Bobby Osborne’s story worth the telling.

How does Bobby feel, for instance, to have been the driving force that changed bluegrass harmony and therefore bluegrass history? “I guess I never thought about it that way. Bill Monroe had a high voice. Then there were others. But I guess that’s right. The modern way of singing bluegrass is basically that harmony we started. I guess that’s right.” He seems almost surprised by this conclusion.

Typically Appalachian, Bobby is at once modest and fiercely proud as he talks about his career. “When I started out, I had a dream, just like everybody else. I listened to the Grand Ole Opry, and I dreamed of being good enough to play there.” He talks about the fulfillment of that dream as if it had been the only natural sequence of events. It’s easy to forget that hundreds of other young men have had the same dream and have had to abandon it.

Besides having his dream come true, there have been many unexpected pleasures along the way. “I’ve already done more things with this music than I ever thought I would, so I feel like I’ve accomplished something from the time I started till now. Sonny and I have had a chance to perform for the President. We were the first bluegrass group to play in the East Room. A lot of people go to the White House but they don’t sing in the East Room. It was a great thrill to do that. At Lake Tahoe, we were with Merle Haggard in the main showroom. There had never been anything there closer to country than Eddy Arnold before. There are a lot of critics out there to appraise what you do, and believe it or not they gave us praise.

“We’ve done a lot of things that I never dreamed we’d do. Like these symphony performances. I never dreamed of singing with a symphony.”

When asked what he feels are the Osborne Brothers’ greatest achievements, Bobby} doesn’t hesitate. “‘Ruby’ and ‘Rocky Top.’ I’ve thought a lot about that. ‘Ruby’ really got us started. When Wesley Rose heard ‘Ruby,’ that was what got us a recording contract. That was in ’57. It was a great song, still is. It’s a standard. Everywhere we go we sing ‘Ruby.’ Then, in ’67, ‘Rocky Top’ came along. I think we’ve progressed in what we’re doing based on ‘Rocky Top.’ Everybody in music should have one song like that. We’ve been lucky. We’ve got two, and I’m proud of that.”

It’s been said that success is being in the right place at the right time. A third ingredient in that formula might be “with the right stuff.” That’s one of the more difficult tasks facing anyone in the entertainment business, given the public’s fickle tastes. There is a fine line between incorporating worthwhile innovations and chasing the latest fancy. That the Osborne Brothers have succeeded in doing just that is an achievement in itself. Bobby has given a lot of thought to the trends in bluegrass.

“Of course, the music has changed a lot. You’ve got new people, new writers, new ideas for songs. Back in the days when we started there were only three or four groups that played bluegrass— Bill Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs and Reno and Smiley and the Stanley Brothers. It was all traditional back then. Each group had its own style. When we came along, we developed a style of our own. In the last few years I’ve not heard anybody with a style that could be recognized so that you could say, ‘Well, that’s so-and-so.’ There should be someone like that.

“I’ve thought a lot about the direction bluegrass is taking. A lot of people are trying to mix bluegrass with rock. Rock music is great but I don’t think it can be played on bluegrass instruments with any effect. There will always be a certain number of people who stick to the traditional sound. That’s another thing. Bluegrass is hard to do. It’s a must for you to be a good picker and a good singer, too. Not many people coming along nowadays can do both. So many people get just good enough to go on stage and then they don’t try any more. I’m a firm believer that no one is as good as he can be. As far as the mandolin goes, I figure I’ll learn more from it before I quit playing. I try new things in my singing. I’m always looking for something to make me stand out.

“As for the direction bluegrass is taking, I’m not sure. Some people say that if something happens to Bill Monroe, bluegrass will die. But bluegrass will never die. Music goes in a cycle. I’d like to see it come back to the way it was when I started before I have to get out of it.”

Bobby doesn’t think that he’ll be getting out of the music business for quite some time, though. The realization of those early dreams hasn’t made him want to fade into the background. “As for my part in the harmony, I wouldn’t take a back seat to anybody. I hate to say it that blunt, but if you don’t think you’re good, you’re not going to be good.

“I feel I’ve got another five to ten years that I can still sing and do what I want to with my voice without it fading out on me. When my voice starts fading out and I hear it getting bad, then that’s it. There won’t be any more Bobby Osborne. I’ll quit.”

There are new goals to reach, new experiences to anticipate. “I’d like to go to England. We’ve been to Germany and Japan and other places, but never to England. I’d like to play there. And I’d like to do some of the bigger TV shows. For the next five years, though, I’d like to go pretty strong at what we’re doing.”

Bobby would like to do a country album, and he’d like to do an album with George Jones. Jones is Bobby’s favorite country singer, and the two have sung together from time to time. “I’ve learned some things from George, phrasing patterns, slurs, things like that.”

Then there’s the movie. “Marty Robbins once filmed thirteen episodes of a thing called ‘The Drifter,’” Bobby explains. “Sonny and I played a thirty- minute part in that. We were moonshiners. Marty Robbins was the drifter and he just showed up in the little community. That was where I got a taste of the action and I always thought it would be pretty good. I never forgot that. That was where I got the idea I’d like to play a part in a movie.”

The movie scene Bobby describes is so Hollywood-stereo-typical of Appalachian life that it brings to mind another stereotype: the poor mountain boys who moved to the city and started this thing called bluegrass. Does the mythical story hold true for the Osborne family? Yes and no, according to Bobby.

“We were never as poor as some people. My daddy had gotten a good education. He taught school for eleven years. My granddad had a grocery store, and a sawmill, and a blacksmith shop. He ran the post office for awhile. When he died, the boys took over. But my dad just got fed up with it. There was no money in teaching school, and he got tired of cutting timber and hauling groceries, so he gave it up and moved to Dayton, Ohio, and got a job with National Cash Register. He stayed there for thirty years.”

Although the elder Osborne got a good education, neither of his sons finished high school before being lured away by the music. Bobby, like Sonny, feels that giving up his formal education was probably one of his greatest mistakes. “I quit school to do this. I wanted to be a basketball player more than anything in the world. I believe if I’d kept my interest in school and gotten a good education, I possibly could have gone on and become a basketball player. But when I heard a banjo, it was all over. In some ways, I’ve gotten a better education doing this than I would have gotten in school. But it’s cost me a lot of good book learning.”

Success has come in the form of recognition, creative opportunities, and money. What does Bobby consider the greatest reward? “I’ve gotten to do what I wanted to do from the beginning. Oh, I’ve had to get another job from time to time. And there have been times when I’ve been unhappy with it. But that’s life. And that’s the most important thing—doing what you want to do.”

Despite the difficulties of those early years, there is a note of nostalgia in Bobby’s voice as he describes the early times. “We’d have a big time on the road. We enjoyed, we looked forward to being out on the road. Making a living at it, yes, but still we enjoyed the fun to go along with it. It was like a continual paid vacation. In this day and time, it’s more like a business.”

Although the relationship has been stormy at times, devotion and dedication to each other have kept the Osborne Brothers together for thirty years. “It’s hard for any partnership to ever work. No two people are the same. So we’ve had our ups and downs. When we reach The Grand Ole Opry, though, we both realized that we came here together and that we had a chance to do something with this music and our lives. It is a partnership and to make it work you have to stick together.

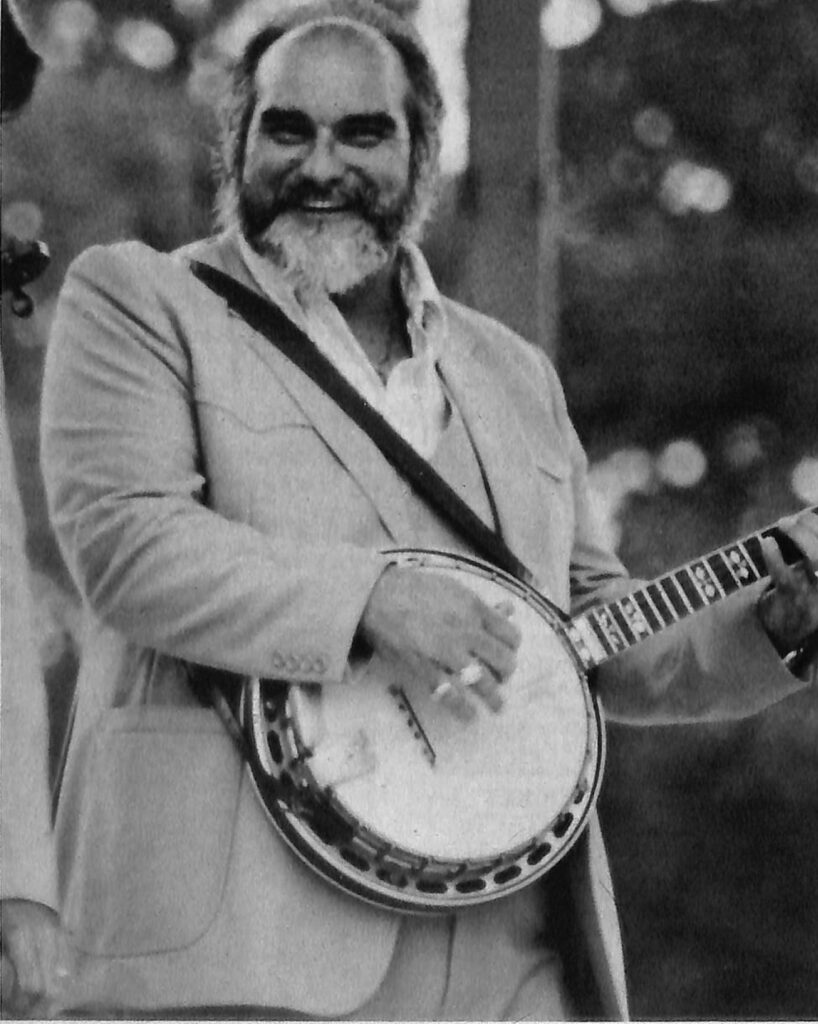

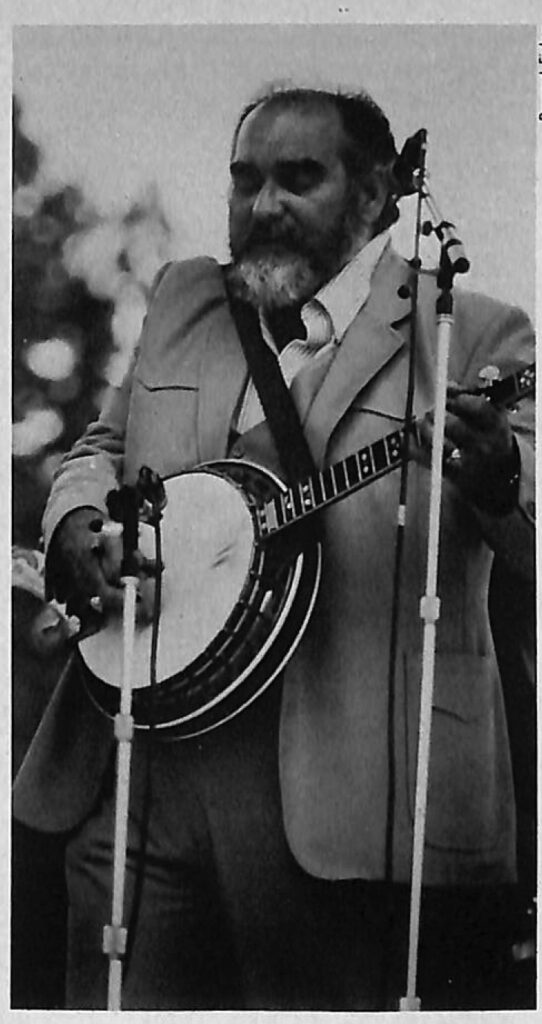

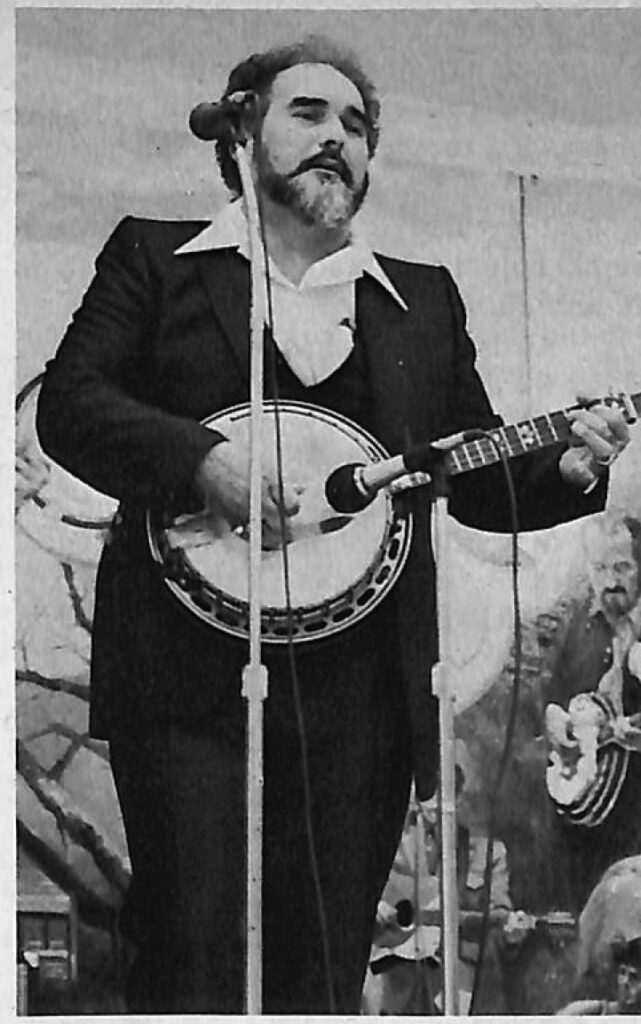

“I would have hated to try to do it without him. Sonny is one of the best banjo players that you’d ever hope to hear in the world. There’s a lot of good ones, but I’d have to put him in front of everyone because he knows what’s supposed to come out of the banjo and he can get it out of it. I’ve enjoyed working with Sonny all these years. It’s turned out good. It really has.”

A partnership such as this one calls for an effort to accommodate the changes in each individual. For the most part, the brothers have a tacit acceptance of those changes. There have been marked changes in Bobby, though, in the recent past, changes that he admits are profound and ongoing. In September, 1982, Bobby Osborne’s priorities were forcibly reorganized. For several months, he had suffered from shortness of breath and chest pains. A visit to the doctor was followed by immediate admission to the hospital and quintuple heart bypass surgery. The news came so suddenly that he didn’t have time to feel frightened or shocked. He recalls the doctor’s words: “One month from today something’s got to happen to you with five of those arteries blocked.”

“I never had time to think about it then. But afterwards, you get to thinking that it can happen to you instead of somebody else. It’s changed me. It’s hard to explain how it has changed me. When I came out, I made up my mind that I was going to do what I had to do to take care of myself, physically.

“Before, I used to eat just anything that I wanted—lunchmeat, chocolate ice cream, and I used to live on eggs. Now, I stick pretty close to what I’m supposed to eat.

“I used to be on the go all the time. When we’d come in off the road, I had two places to take care of, my house and the farm. There was always something to do, keeping the grass cut, keeping both places up. I never had any free time. Now I’ve got someone to look after the farm and I’m looking forward to having nothing to look after, really. That’s all been part of the change.”

How Bobby feels about performing today depends on the place he’s playing. “There are festivals where you go and the crowd is hollering, maybe dancing in front of the stage, kicking up dust in your throat while you’re trying to sing. That’s when I start looking at my watch. Then there are other places. We do a festival in Chicago. When you get out on stage, the people sit just as quiet. They know the songs you do and they appreciate them. You enjoy playing a place like that. I like the Station Inn in Nashville. I go down there and I’ll get up on stage and sing a little bit. The people there sit and listen, too. So many places you go, as long as it’s a big loud noise, that’s all they want.”

He admits that change is still going on, that he hasn’t sorted it all out yet. Perhaps the most telling evidence of the changes in Bobby is expressed in his views toward the zest for life he feels. Of the early years, he says, “I didn’t think of danger. All I thought about was living!” Today that enthusiasm for life is indicated somewhat differently: “One thing I’m interested in is my health, taking care of myself physically, my jogging. I guess it’s because I have to.”

Bobby is not grabbing life in lusty fistfuls any more, but he’s allowing himself to savor the measured pleasures, seeking out quality, taking time to take time.

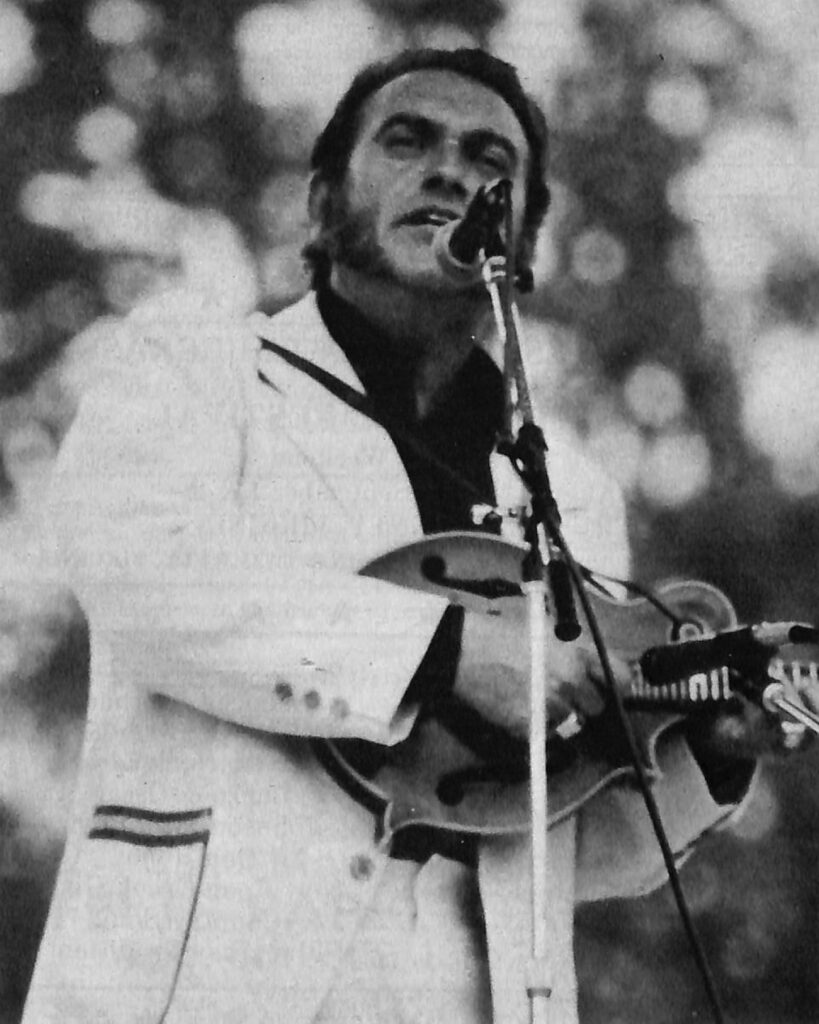

Sonny Osborne—Driving For the Music In His Mind

The first time I met Sonny Osborne I was terrified—and then very impressed. Terrified because Sonny was displeased, and a displeased Sonny Osborne has the countenance of an angry god. Impressed because after watching and listening to him, I came away feeling that, in many ways, success hasn’t touched Sonny at all.

I had arranged to talk with Sonny between sets at a club just outside Charleston, West Virginia. During the first set, it became apparent that something was wrong with the sound, something that wasn’t going to be fixed. This was a small club, and although it was full, it certainly wasn’t the biggest crowd Sonny would play to this year. The audience didn’t seem to be bothered by the sound problem. Fans called out requests as if they had memorized every song Sonny and Bobby had ever recorded. From the audience’s side of the stage, the show was a success.

Not so in Sonny’s view. The poor sound was the source of his displeasure. As we were introduced, he said, “This isn’t a very good time.” It wasn’t. He tried to be polite, but his replies were brief and he was obviously distracted by the technical flaw in his performance. As I left I couldn’t help wondering if a single off performance in a small club could really mean that much to him, and if so, why?

The Osborne Brothers did, after all, have a reputation that preceded them. The emcee that evening had introduced them with the line, “These guys are legends!” Indeed they are, and legends can, supposedly, rest on their laurels a bit from time to time. Why couldn’t Sonny?

That question, among others, led to another meeting with Sonny. Why, after all the years and all the success, couldn’t he relax? Why was he driving so hard?

“I relax when there is something to relax about. But if you’re going to be in business, you’ve got to be in business. You can’t just be into it a little bit and out of it a little bit, in my mind anyway. You work as hard as you possibly can, as hard as you did when you were fifteen, sixteen, seventeen years old. If you don’t do it that way, then you’re cheating yourself and everybody else. While you can make it it’s best to make it because it won’t always be there. That’s the reason for that.”

Sonny says that this business won’t always be here, that you can’t depend on it. What would he do if that happened, if he suddenly woke up one morning and there were no more bookings, no more festivals, no need to load up the bus because there’s no place to go?

“Nothing. That’s why I’ve worked so hard. This is it. I could quit now if I would like. But I don’t choose to do that. It might be greed to an extent, I guess. It could be just the need to hear the music that I know we can play. Many things go into that. You don’t just say this is the reason that you do something. There are many, many little things that go into it.”

Though he works hard, Sonny wishes he had time to work even harder. Instead, he and Bobby concentrate on the things they do best. “I still don’t think we work as hard or do as much as we possibly could do. I think there are things that we leave unturned. For instance, in the publishing business there are several things we could have done, that we could have done well with, I think, but we just don’t have or won’t take the time to do it.”

In music, where talent is the commodity, artistry often peaks after a few years, and little is left but repeat performances. For Sonny, what’s left is another reason for staying in the business.

“From the time I started playing I wanted to play exactly like Earl Scruggs. Now I want to play like what I hear in my mind, and develop what we can play rather than what Lester and Earl played or what Monroe played or the Stanley Brothers, or Jim and Jesse. I want to hear what we can do now, and so that’s changed somewhat. And as time has passed, and our name has gotten better and bigger, instead of our looking to a Flatt and Scruggs, young people now are looking to us. So you strive for perfection like they did, just to satisfy the drive that you have to perfect what’s in your mind.

“The business side of it to me is a lot like the music side. You work as hard as you can to perfect a certain kind of break or note or something like that, and in the business side of it you work hard to perfect that, too. You work as many dates and get as much money out of it as you can. Everybody says you’re not supposed to look at the commercial part of the entertainment business of music. Just play for the music itself. I think that’s bull. Everything in your life is commercialized. We all think that way, too. It might look good, or sound good, but you still can’t make a living by not being commercial, just for the music itself. So there’s more, a lot more that goes into the business side of music. You work as hard on that as you do on the other.”

No matter how much effort is directed towards reaching personal goals, there is really no guarantee in this business that the results will be worth the struggle. Bluegrass music is not known for the creature comforts of the nine-to-five business world. So, when Sonny reveals what this business has given him, it’s somewhat surprising.

“As close to security as I can get, with the knowledge that it can be gone. The business itself could be gone in a year. The security to know that I wouldn’t have to do things that I didn’t want to do. It’s put one child through college and has almost put another one through. I guess that’s it—security.”

And at what cost? “My life. It’s a pretty fair trade. That’s about all any of us have to give—our time and what we are, what we know mentally. We trade that for security. And I kept some for myself.”

The road hasn’t always been easy, though. Given a chance to do it over, there are some things Sonny would do differently. “Number one, I would have gotten a good education, which I don’t have, which has cost me a great deal, not in money but in time. With an education you are able to think your way through and not have to go trial and error, and that’s the way we had to do it because we weren’t knowledgeable enough to do it the other way. That’s the first thing I would do.

“I would stay completely away from alcohol and speed, which I didn’t do, and I had to learn the hard way. They took a little bit of my mind away. Of course, they gave me some things in return, I guess. I don’t know what yet. Let me see, they probably shortened my life by ten or fifteen years. I won’t know that until the time comes. Maybe in some other life. Speed kind of helped me in a way, though, because with speed you’re able to out think yourself. Alcohol is really bad. I think that is what I would stay away from most of all—alcohol and all kinds of drugs.

“I’ve been clean—alcohol, since 1968, and the rest of it, about six or seven years ago. I’m so straight that I can drink a cup of coffee and get like this (he shakes). It took its toll. I can tell the difference. But I’ve been fortunate in that I was able to give it up without professional help. I just made up my mind to do it, and did.

“As far as the business side of it, I think we did what we could do in the early days with the knowledge we had. There wasn’t anybody to ask, either, in those days, because we were among the very first bluegrass bands in existence. Besides us, there was Lester and Earl, Monroe, the Stanley Brothers, and Jim and Jesse. We started in ’53, so we were right in the beginning. There was nobody there to ask what was right or wrong. I really wouldn’t change the music all that much.”

There are special circumstances inherent in working with family. For the Osborne Brotehrs, a sense of mutual respect and understanding form the basis for a working relationship that spans three decades.

“When you’ve got a person like I’ve had to work with (Bobby), you’ve got to realize that a unique and different person such as that is going to be one of many different moods. In a way he’s a genius because of his ability to do what he does so easily. Everything he does is natural and there is only one of him in the world. There is nobody who can quite duplicate what he does, so it’s not easy, at times, to work with him. And yet, I wouldn’t take anything in the world for the experience. It’s like building a house. If you’ve ever built a house from the ground up, you wouldn’t take a million dollars to do it again. It’s about that same situation. I wouldn’t have missed this for anything. It’s been good. It really has. We’ve seen a lot of important things and been to a lot of important places that people pay millions of dollars every year to go see. And if I had the choice to work with him again, I’d do it.

“I know my role and he knows his. And I never have to ask him anything and he never has to ask me anything. Onstage, I can look at him and I know what he’s going to do, and he does me the same way. He realizes what I am musically, and I realize what he is musically. I respect that and he respects that, too. I enjoy hearing him sing and he enjoys hearing me play. It’s good.”

It is good. That combination has spelled success for the Osbornes. Sonny talks about their achievements, the ones that have meant most to him. “As far as music is concerned, I guess the most important thing is the origination of the harmony which hadn’t been done before. That was in 1957 or 1958. It completely changed bluegrass harmony around. It opened another door for people to go through.

“In terms of something that you say you are proud of, I would say when we worked at the White House. We were the first bluegrass group ever to play inside the White House, in 1973, for Richard Nixon. The place is awesome—it really is. We got to tour the whole thing, just wander around for a whole night.

“We were the first bluegrass group ever to play at Harrah’s in Lake Tahoe. It was frightening. Those two things really stand out in my mind. For a sense of pleasure, something that I was glad I did, was when Boudleaux Bryant, who wrote ‘Rocky Top,’ ‘Georgia Piney Woods,’ ‘Tennessee Hound Dog,’ and ‘Muddy Bottom,’ among others, called me one night. He said that we had a hit. I said, ‘What?’He said, ‘Rocky Top.’ To go back a little, our contract was up with Decca at the end of the year. ‘Rocky Top’ was released on Christmas Day. They didn’t say anything to us about having a hit record and we didn’t listen to the radio enough to know that much about it. And so we had a hit record. But they [Decca—now MCA] were trying to get our name on a contract before we knew that. We’d already signed the contract when Boudleaux called and said we had a hit.

“‘Rocky Top’ had been out three weeks and had sold 84,000 records. That’s unheard of for bluegrass, and it’s really pretty good for anybody. ‘Rocky Top’ has since been recorded over a hundred times. It’s one of the official state songs for Tennessee. It’s one of the best-known standard songs in the world. It’s equally recognized in Japan and Sweden and Germany, anywhere.

“It really gives me a sense of pleasure to know that they all use our arrangement, that we did that. It opened a door that would not have been opened and that has not been opened for any other bluegrass group, except maybe Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. It opened the door that has allowed us to go into the part of the business that no one in our whole side of the business— bluegrass—has been before or since.”

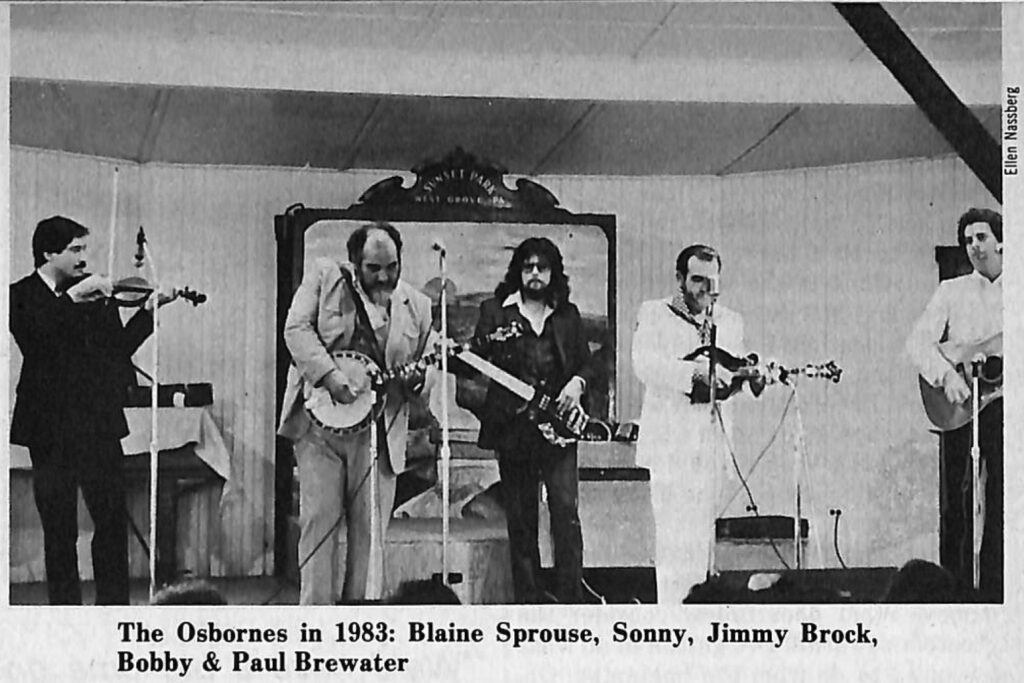

Sonny says this with a mixture of pride and awe in his voice. It’s that humility and realness that stand out in Sonny. He’s proud of his work, and proud of what he considers to be the best Osborne Brothers band ever (Paul Brewster, Jimmy Brock and Blaine Sprouse). But he’s not resting on his laurels. He hardly realizes that they’re there. He’s working too hard today to look back. He’s still making it, and that’s part of what makes the Osborne Brothers’ music as good today as ever.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

There will never be another Osborne Brothers. On the subject of Sonny’s sensitivity to the sound system, I saw them at a Berkshire Mts./Winterhawk (not sure which edition) festival. The sound balance was bad (as it often is, the sound people can be quite ignorant of acoustic music). Sonny got to the front of the stage and told the soundman: turn that mike up, that mike down. For circa 10 mics! Then the band played, and the sound was great!

He could hear from the front of the stage what was needed! I was happy too.

Sadly, the soundman still thought he knew best and soon ruined that perfect balance.

Yes it’s so sad the first generation of bluegrass is not gone.