Home > Articles > The Archives > The Dry Branch Fire Squad

The Dry Branch Fire Squad

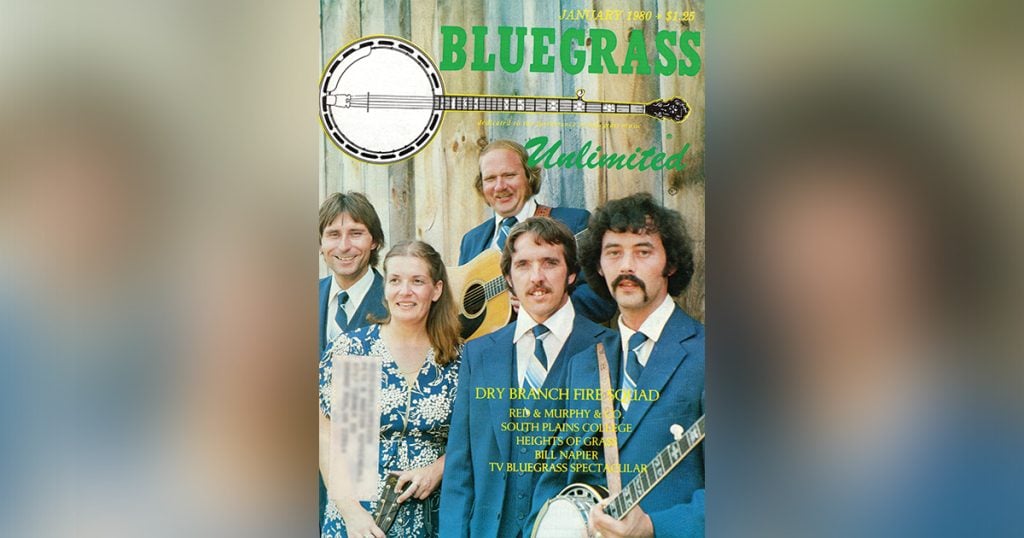

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1980, Volume 14, Number 7

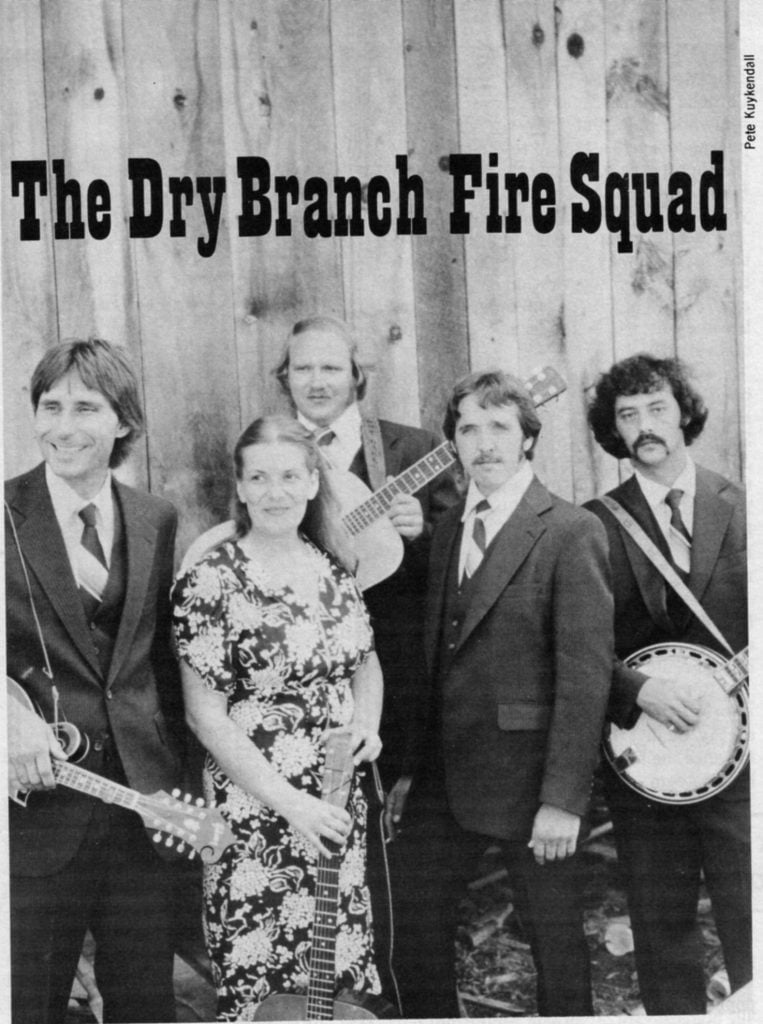

What do you get when you cross a hillbilly, a fisherman in a cowboy hat, a mechanic, and a whittler, with satirical wit, meticulous musicianship, and a great respect for the heritage of bluegrass music? The Dry Branch Fire Squad, of course.

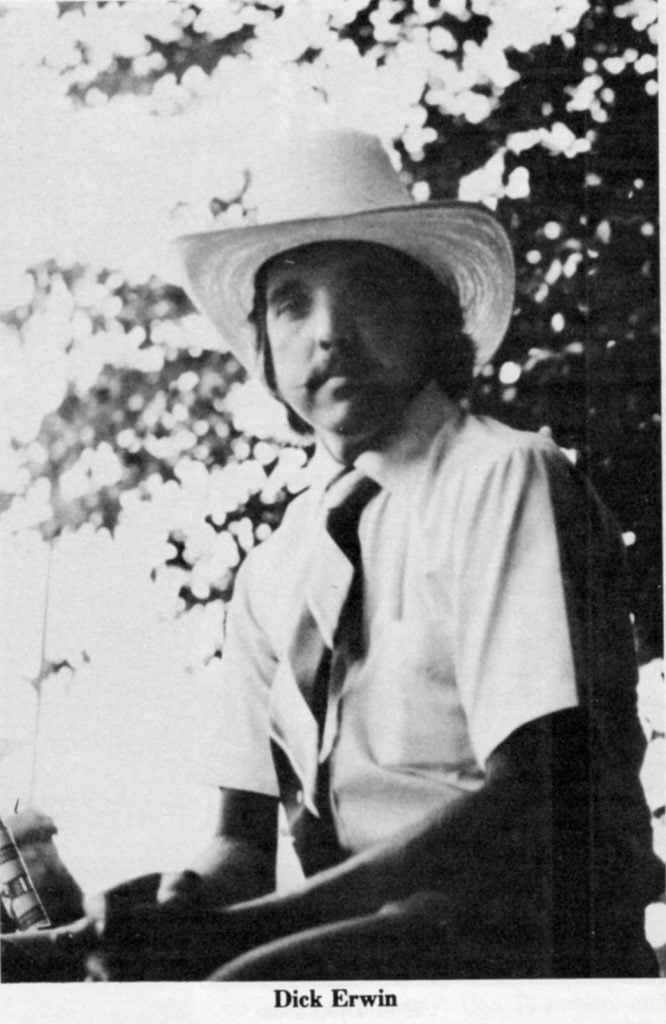

And who are they? Well, the hillbilly, by his own proud admission, is Ron Thomason (“But I’m the onliest one that doesn’t talk with a Southern accent”). John Hisey (who loves to fish almost as much as he loves to play banjo) is introduced as “Lonesome-Hobo-Cowboy John.” Johnny Lee Baker (Yes, folks, he is related to Kenny—he’s his son, to be exact) is a maintenance repairman in “real life.” Dick Erwin will even sit and whittle at a festival when he’s not performing or jamming (but promises he’ll never use his bass fiddle for whittlin’ wood!).

As you might have guessed, the Dry Branch Fire Squad is not exactly a typical bluegrass band. Individuality is a trademark of this group. In fact, Ron says, “Actually, we’re a satire on bluegrass bands.” That is, they satirize some of the rituals of performing. For example, they never introduce themselves by their real names on stage, and Ron will announce “We went and got hats, ‘cause hats are how you can tell you have a bluegrass band.” Nor is their material chosen from the usual fare. “We don’t know any hits,” says Ron. Even the name of the band is a little off-beat (even among the far-out band names that abound today). Ron wanted something to convey the idea of a group—the word “squad” had occurred to him—one day he was driving through Dry Branch, Virginia—and, well, the rest is history. They do make one concession to conformity—matching outfits. But Ron explains that by announcing, “We mugged a bowling team on the way down to the stage,” or something equally preposterous.

Who they are is very much played down. As Johnny Lee Baker explained, “Nobody is real serious about themselves.” They are, however, very serious about their music. You will never see them cutting up during a song, yet there is plenty of comedy between songs. What have come to be called “Thomasonisms” abound. You’ll hear things like “Is he talkin’ hillbilly?”, “All city slickers are entitled to laugh at any of these lyrics,” or “This is a banjo number where he renders and saws, and tunes, and thumps, and absolutely manipulates every moving part of a banjo.”

This unique combination of lots of humor with complete seriousness about their music produces a show that is rare these days. Ron commented, “We’ve mutually decided we’re not going to just act silly, to sell ourselves. We try to present as entertaining a show as we can without ever prostituting the material. I think people enjoy hearing this good bluegrass music. People that hear our show go away pleased, a lot of them—and I’m glad of that.” Or, as I overheard a festival-goer at Beanblossom commenting to his friend: “They don’t break the tradition much, yet they’re not afraid to stand up and entertain you, which is a refreshing change. As far as I’m concerned, they’re the best new bunch they’ve had here in years.”

The D.B.F.S. is dedicated to preserving the duet in bluegrass, and they do it in a grand way. Ron Thomason and Johnny Lee Baker sing together like they’d been doing it for years, but it’s only been a little over a year. The sound is tight harmonies and a voice blend usually found only in brother acts. Johnny Lee says, “When Ron asked me to join the group, all he knew was I could sing a harmony line. Neither one of us had any idea it would blend like it did. It just amazed us all.”

Thomason and Baker are also masters of a cappella singing. You can hear all the elements of the body of the song and feel the rhythm structure within the music, though there is no accompaniment. It is as if their singing and the song blend into an entity that exists apart from other realities at that moment. The exquisite harmonies and quiet, intense drama of their singing in a song about a little orphan girl even quieted a noisy club crowd. Heads began to turn and the whole crowd was completely quiet before they had finished the second verse. Even the few standards they perform, such as “Roll in My Sweet Baby’s Arms,” or “Cripple Creek” have a new dimension when sung Thomason-Baker style.

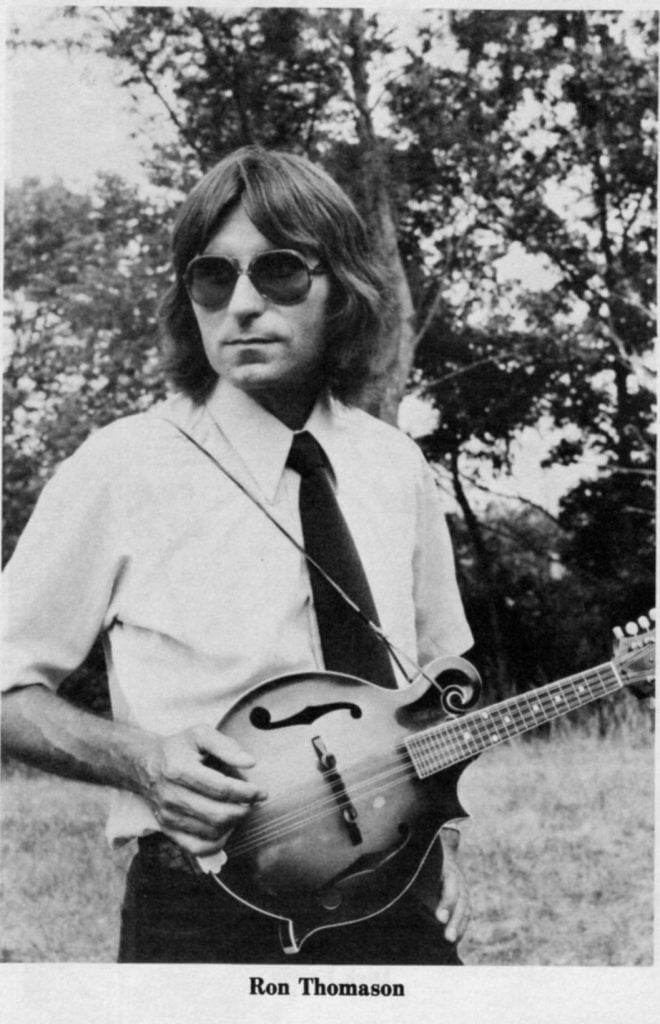

Ron Thomason, the lead singer, is a native Virginian. Though his singing is an integral part of the success of the band, he feels that selecting the material is his most important contribution to the group. Since he considers the band “Spokesmen for a way of life,” he thinks in terms of the heritage of the songs. His goal is to impart the feelings of the people who originally propagated the music. Watching Ron perform, one senses this deep respect for the music, the songs and the people who made those songs—in the way he sings, and the way he plays. His voice has a commanding quality, and his mandolin playing ranges from soulful to “hot,” from delicate to driving.

Ron was born near Honaker, Virginia, and spent much of the time during his younger years back and forth between there and central Ohio. He remembers on these rides with his dad, listening to the Bristol, Virginia Farm and Fun Time and the Grand Ole Opry. “We’d hear the Louvin Brothers, Flatt and Scruggs, and the Stanley Brothers. I can really vividly remember at an early age, when I was just four or five, hearing songs like ‘How Mountain Gals Can Love.’ I can even remember the titles and kind of where I was when I heard them, and I really liked that music.”

Ron learned to play the mandolin and guitar when he was in school. Right after he got out of college he joined a band with Frank Wakefield, Howard Auldridge and Tommy Boyd. “That’s a lot of good musicians to have all right in the same spot, to learn music from. They were centered right around central Ohio, which had a lot to do with why I came here after I got out of college,” Ron explained.

Ron now lives in Springfield, Ohio, and is assistant principal at a junior high school 10 miles from his home. When there’s no snow on the ground, he rides his bicycle to work, because he believes that making an effort to stay in good health is very important to a musician’s way of life. He told me, “I personally believe that one cannot do strictly music for a living. Not from the standpoint that you can’t make enough money, because you can, and I have in the past. But I won’t do it because I think work’s an important part of the culture and also I feel that it’s bad for your health.

“The whole ethics of the road—the whole road thing—is so bad for you. You have to work, have a job and these things in your life if you’re going to stay healthy enough to play music, which takes exceedingly good health, I think. You have to have a schedule you’re on, and you can break this schedule up and let music in—but you can’t center your schedule around music and stay healthy. Bill Monroe is singularly one of the few people that’s made a living at it and stayed in good health, and he’s done this by means of work. It’s nothing to see him working in the field—go to Beanblossom, he’ll be out there with a scythe cutting the weeds!”

Ron does all the MC work, and it is truly a treat to hear him. Again, he draws from the country heritage from time to time,and weaves it all in so skillfully. (Or, as one fan bluntly put it, “He’s funny as hell!”)

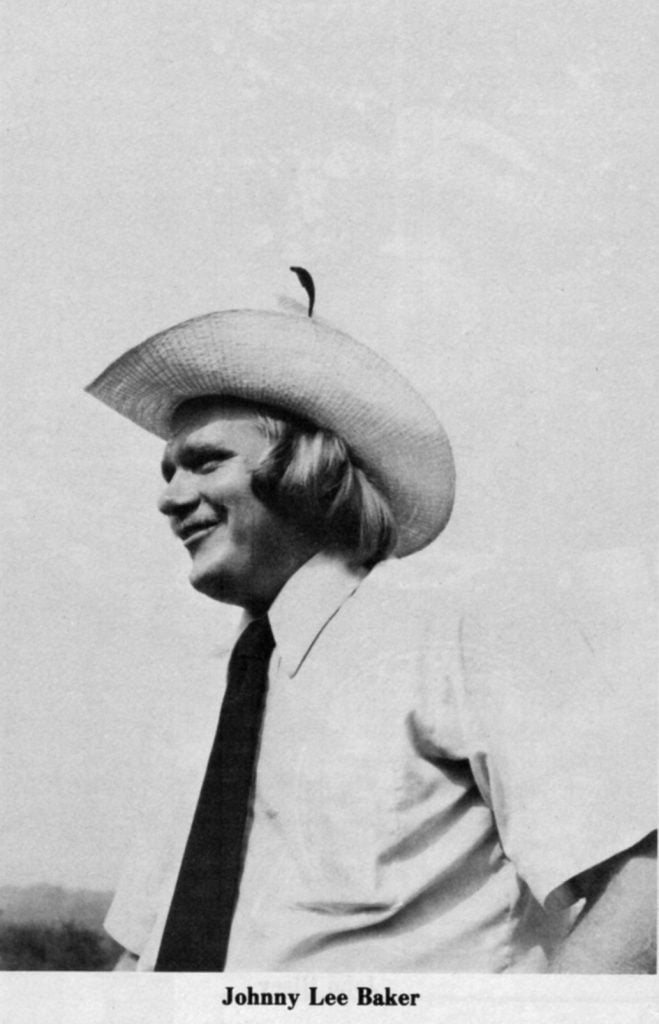

Johnny Lee Baker, who grew up in Jenkins, Kentucky, sings tenor and plays rhythm guitar. He always loved singing, but never sang any harmony until two years ago. He grew up listening to his father play, and figures he must have just “soaked up” a lot of that music. “Had to’ve,” he says. “Notes that I sing in songs that I’ve never tried to sing a harmony part to, I can never remember hearing them consciously, but I know I’ve had to, or I would’ve never come up with them.” How did he learn to sing harmony? “Seems like it came easy. I don’t remember ever trying to learn a part. Just, if I knew the melody, I could more or less write my own, because I try not to sing a tenor part even like Monroe, or Stanley, or anybody. I’m not saying I could do it better, or as good, but I want it to be me. I just sing my part—it won’t be like theirs. It’s gonna be me. So far it’s worked.” Indeed, it has! Bob Leach, former banjoist with the band, commented, “The most enjoyable part of this group, the big highlight for me, personally, is the duet singing.”

Johnny Lee’s stage presence is sober but not self-conscious. His good, strong tenor has a “lonesome” quality, and his timing is unique. Sometimes you’ll even think he’s going to miss a note entirely, but then, there it is—right where it gives you chills to hear it!

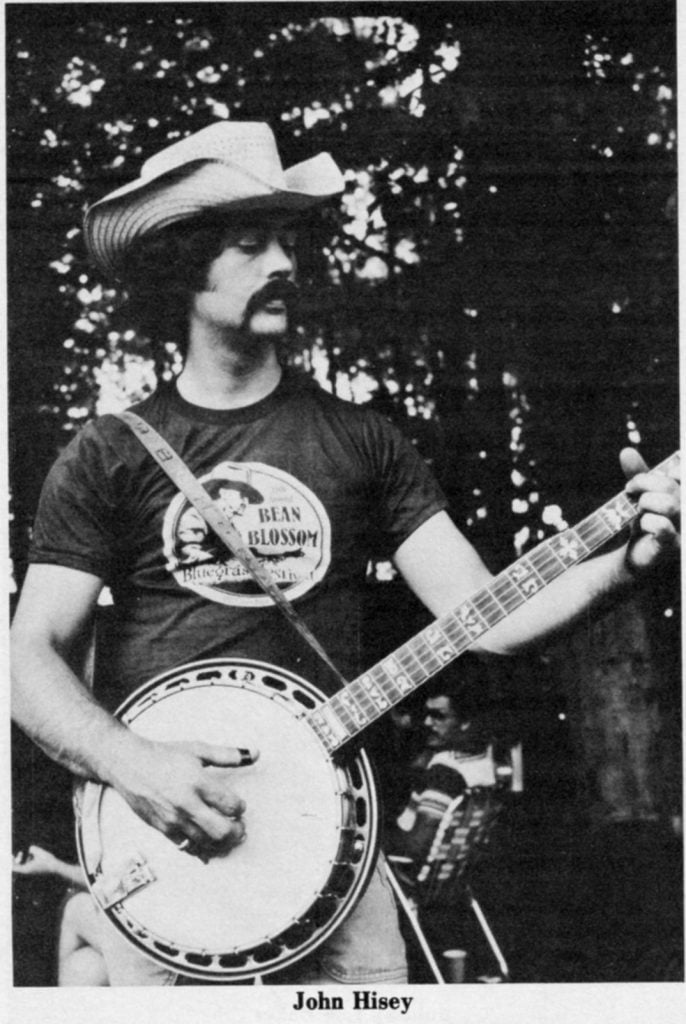

John Hisey grew up in the Springfield, Ohio, area. For as long as he can remember he had wanted to play the banjo, so about 6 years ago he bought one. As he learned to play, he says he found it “really exciting.” He had grown up listening to a lot of gospel music, and has now discovered that playing bluegrass banjo is really “his thing.”

John had played with a local group the past few years. He had known Ron a long time and been listening to the D.B.F.S., so when they needed a banjo player a couple of months ago, he was pleased to have the opportunity to step into the position.

The banjo player he admires most is J.D. Crowe. “I think he’s about the best I’ve ever heard,” says John. “He’s had a lot of influence on my playing, ‘cause I like to stay kinda straight—you know, straight bluegrass.”

Mary Jo Dickman, who works a part of almost every show with the band, sings a high baritone part in a trio, or in the gospel quartet. She lives in Dayton, Ohio, where she was born and raised. She had always done a lot of harmony singing at home with her sister, and had listened to folk, and loved all kinds of acoustic music, but admits, “When I heard bluegrass I just went, ‘Now, this is what I’ve been waiting to hear.’ I felt like I’d been saved!”

Mary Jo has a warmth and magnetism that comes through in her singing, and her enthusiasm for the idiom of bluegrass extends even beyond the music. She says “I’ve gotten so charmed by the people in bluegrass. You see the same people every year and you can sit down and talk or play music together. They are good people—people I like to be around—lots of energy—people that enjoy music.”

Dick Erwin, who plays bass and sings baritone in the quartet, was something less than enthusiastic before he’d been exposed to any bluegrass music. As he tells it, “Johnny Baker (before he joined the D.B.F.S.) asked me to go with him to hear the band. I said ‘Nah, I don’t want to go listen to no bluegrass.’ But, he talked me into it, so I went down with him that night—and never missed a Thursday for a year and a half!” That was in October and when summer came around, he attended seven festivals. “I really realized just how much I loved bluegrass when I spent nine days here (Beanblossom, Indiana) and I didn’t want to go home. I’d been listening to it 9 days straight, 24 hours a day and—I didn’t want to go home!”

As we sat in the shade of those big old trees, a pot of beans simmering on the fire in front of us, and a jam session coming to life just beyond that, Dick groped for words to explain his love for the music this band makes. “I think it’s the emotion that’s there. You can play a song and, musically, play it perfect. But if there’s no feeling there, it’s no good. If you’ve got that feeling, it’ll come across—whether it’s on a tape, a record, or live. It’s magnetism. The people feel it. It’s like you are sharing your feelings.”

The Dry Branch Fire Squad—indeed, “spokesmen for a way of life”—a way that comes from the past, and yet, is very much woven into the fabric of their lives today.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I wonder where John Hisey and Dick Irwin are now. I bought my bass off John and Dick played it on stage at the festival where we planned to bring it home from. I’d just like to say hello