Home > Articles > The Archives > Spectrum

Spectrum

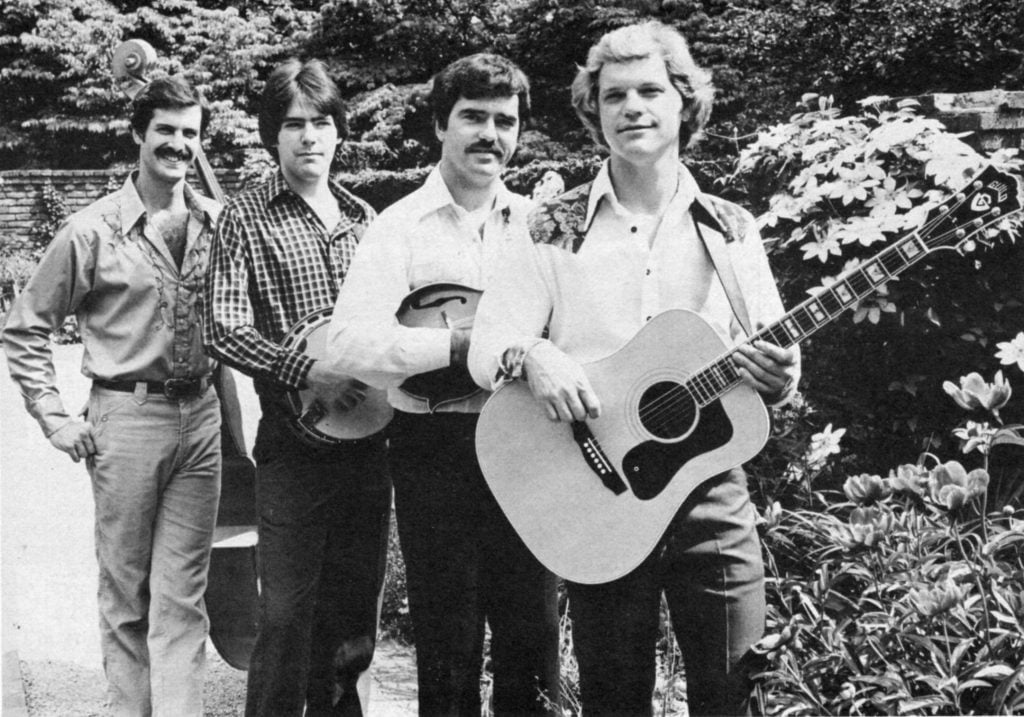

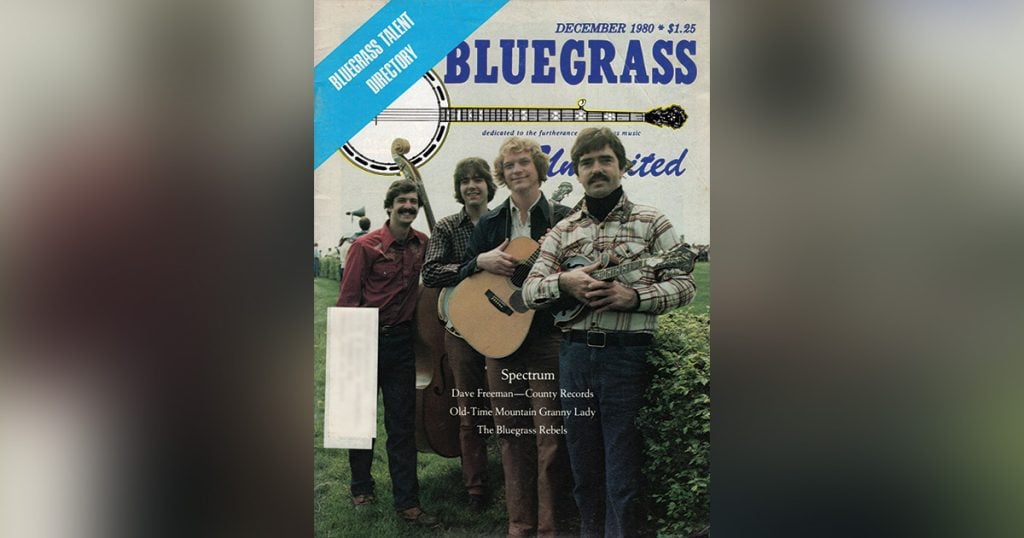

When the four of them first got together and decided on a name for their new group, they chose Spectrum, to indicate their wide range of musical interests and abilities.

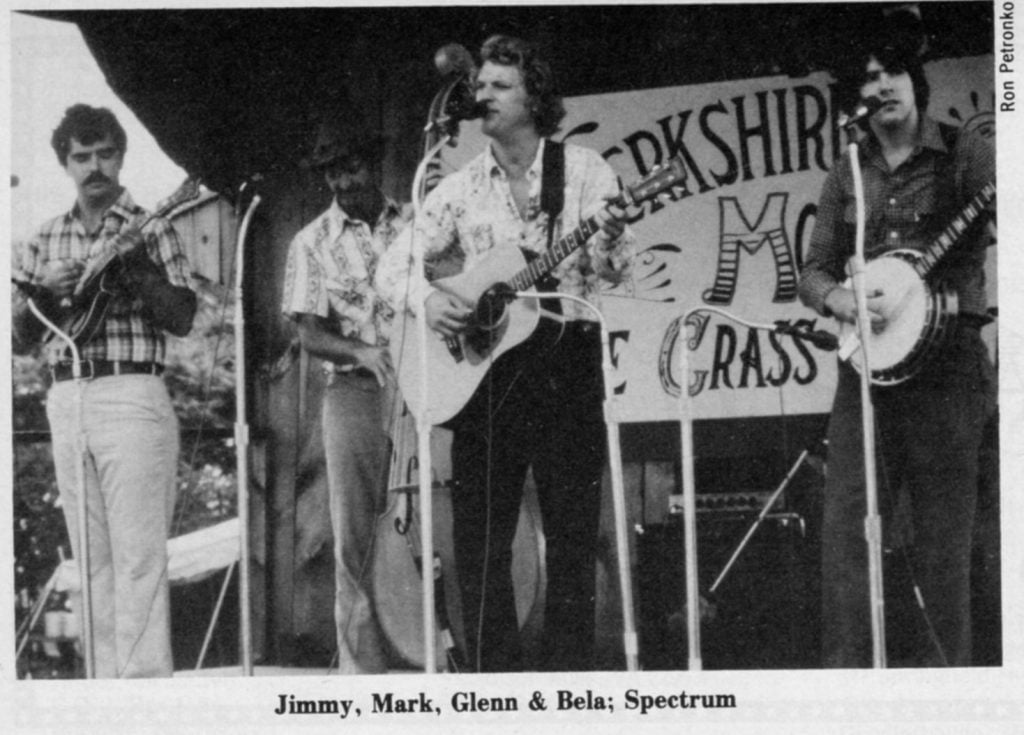

The name is apt, as the music they produce together stretches from 1930’s popular music through Texas swing to jazz and country, while working within the framework of bluegrass instrumentation. Another name, however, equally suitable, might well have been Convergence, because Jimmy Gaudreau, Glenn Lawson, Mark Schatz, and Bela Fleck are four very different individuals, each of whom brings his own background and influences to their joint effort, like highways from different areas forming a major roadway that leads in a new direction. The result of this merger is not quite like anything heard before.

In addition to their talent and experience, they evince a musical sense of humor and exploration, and the energy to attempt something different, to push back the edges of what has gone before. It is not bluegrass, by the strictest definition, but it is exciting and interesting music. Whatever you want to call it, it works.

Gathered around for a recent conversation, in which each of them talked a little about his earlier musical experiences and his feelings about the new group, Jimmy expressed what might be called a “group philosophy” as well as any of them, comparing their kind of sound with that of the early Country Gentlemen.

“You knew instantly,” he said, “when you put on a Country Gentlemen record, that it was a different type of bluegrass. They were forerunners and innovators of that type of sound. It all had a lot to do with the personality of the group.

“(Eddie) Adcock’s banjo struck you as completely different, not only in the way he played, but the tone he got out of the banjo was unlike anything else you ever heard. That particular band was made up of four individual stylists that happened to work well together.

“I don’t think it was something they tried to do…I don’t think they started with that intent. I think it just happened that way. They couldn’t help but come up with a sound that was unlike the traditional bluegrass of that day.

“We are also individual stylists, and can hopefully do in our own right what they did in their way. I relate us to them not only because we use the same instrumentation, but because the personnel in this band are individually different. Glenn isn’t a one-way vocalist, and Bela surely isn’t a limited banjo player. Everybody has developed his own style in this group.

“We went into this thing to come up with a musical concept and also to do anything we could do well, so the name is just a reflection of the types of music we do in the act.”

Spectrum succeeds in eclecticism where many other groups have failed, because their differences come naturally, and are not assumed to follow popular trends. They are not a bluegrass band with a rock and roll beat, nor do they merely play top forty hits with bluegrass instrumentation. Due to each member’s earlier involvement with other kinds of music, the band is a blend of a number of elements which produce a sound that is uniquely Spectrum.

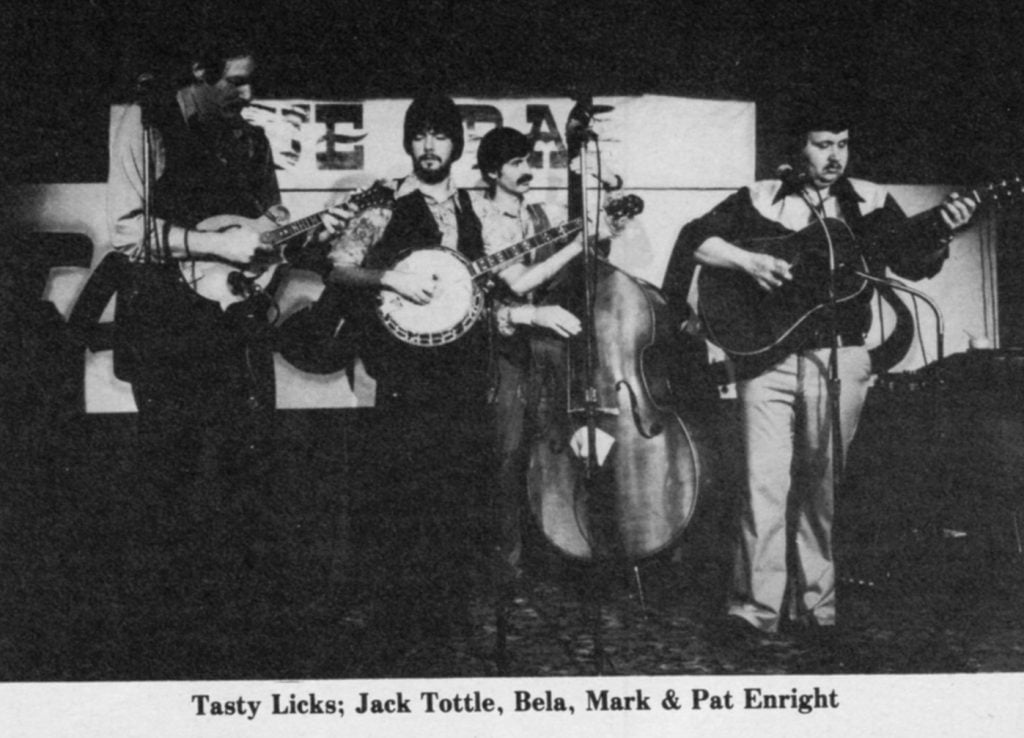

Bela Fleck, banjo player and youngest of the group in years, although his professional experience is impressive, has come to the attention of banjo buffs in the last few years through his innovative playing and his great technical ability. Subject of a feature article in Banjo Newsletter (Vol. VII, No. 1, November 1979) he has recorded with Tasty Licks, his previous band, on “Tasty Licks” (Rounder 0106) and on their final album, “Anchored To The Shore” (Rounder 0120). His own recent instrumental album, “Crossing The Tracks” (Rounder 0121) has been very well received, and he has made “guest” appearances on recordings of numerous other artists.

His sense of humor is not limited to his music. Born in New York City, he makes light of his metropolitan background: “I learned my music from concrete, and picked it up from roaches!” he said. “I played at the age of fifteen at hoots and group sings. First money I made? These guys promised me I’d get paid this week!

“After I’d been around for awhile, I played with Brownstone Hollow, a city bluegrass band, then another called Wicker’s Creek, then Tasty Licks. I moved to Boston in 1976 for the Tasty Licks gig.”

Like many before him, and probably hundreds yet to come, he was first brought to bluegrass by the music from “The Beverly Hillbillies” television program, which he heard as a child. Few other banjo players, however, have taken jazz lessons from saxophone players, or have played five-string in a jazz band. Bela has done both.

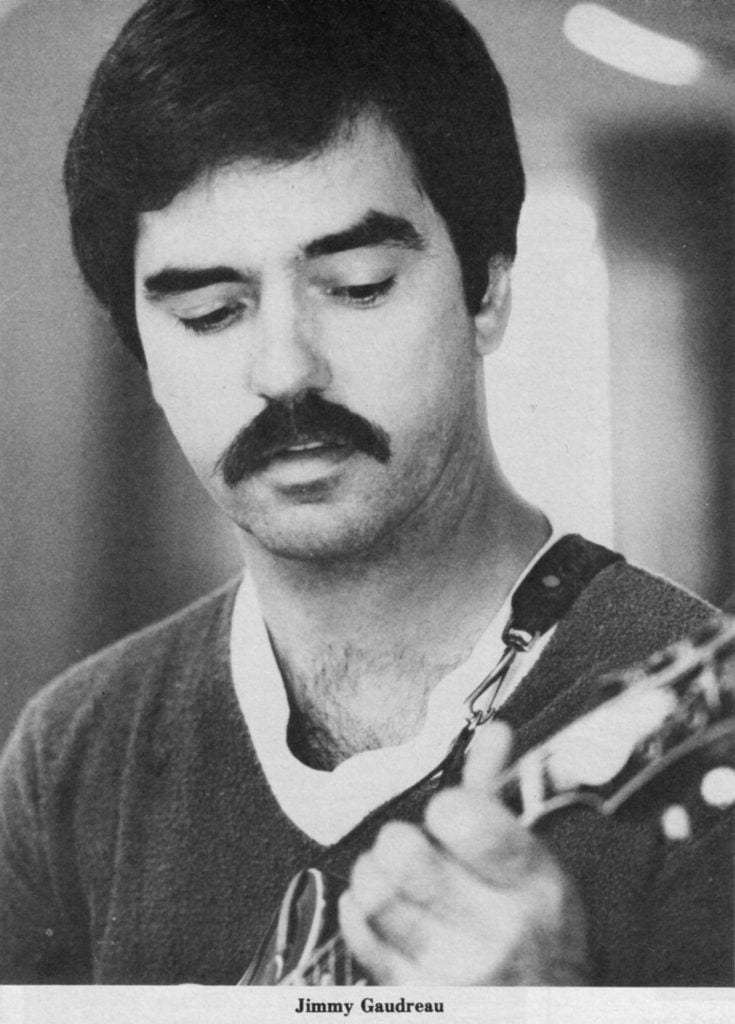

Jimmy Gaudreau, Spectrum’s mandolin player, has a name well known to bluegrass fans. He was bom in Wakefield, Rhode Island, and said, “I like the old country/western music and listened to stuff like Webb Pierce, Red Sovine, and Hank Williams. Never became interested in bluegrass until I heard Scruggs in the theme from “The Beverly Hillbillies.” You didn’t get exposed to bluegrass, living in the North. It was nonexistent on radio. I learned the banjo first, when I had been playing guitar about six years, I guess, and then took up mandolin at the age of sixteen.

“I played with a band called Silvertones in junior high, playing electric guitar. By fifteen, I was learning bluegrass while making money with a dance band, Jimmy G and the Jaguars. We had big crowds and were the hottest band on the beach!

“All during the folk boom, everybody was buying acoustical instruments, and we heard about a guy in Connecticut who’d been playing for years and we—Bill Rawlings and myself—had hurried over to see him. It was Fred Pike.

“I had met Mark Kitchen who worked with my father in a textile factory. Bill and Mark and myself were playing with a banjo player who went off to the Air Force. We got together with Fred to form The Twin River Boys. I was nineteen, and stayed nineteen for years!”

Jimmy at the age of nineteen, or thereabouts, may be heard on the now scarce album, “Twin River Boys Play Authentic Bluegrass Folk Music” on the Osage label.

“Directly from that I went into the Country Gentlemen for two and a half years, then the II Generation for about a year, then Country Store about three years. At the end of 1975 I went with J.D. (Crowe) for four and a half years, then Spectrum.”

In addition to his many recordings with the above groups, Jimmy issued an instrumental album of his own, “The Gaudreau Mandolin Album,” (Puritan 5011) in 1978.

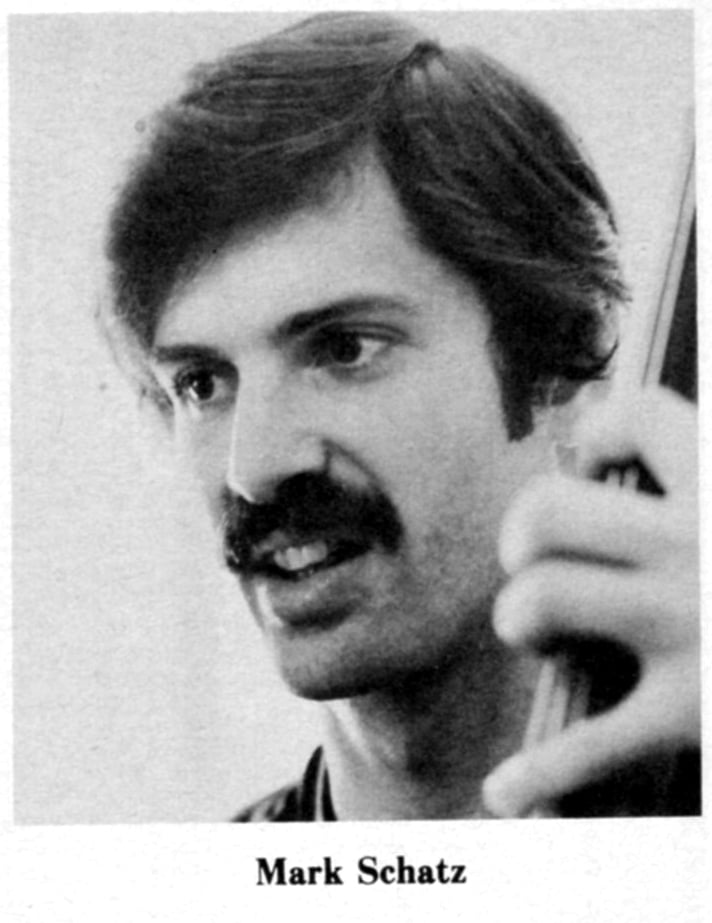

Mark Schatz, bass player for Spectrum, was born in Philadelphia, and after moving around with his family in Minnesota and Michigan, settled in Boston in the middle 1960’s. “My father played clarinet and harmonica and was pretty musical,” Mark recalls. “I remember him whistling improvisations to Sousa marches on the radio. My sister played piano, and I played little bits on anything I could find: baritone horn, harmonica, accordian. My sister taught me to play guitar at the end of junior high school, and I played folk music.

“I started playing cello when I was ten or eleven. In Boston, I took lessons, and played in the school orchestra. I switched to bass as there was less competition. There were lots of cello players!

“I found a Sousaphone in the closet at the school orchestra, and my father said, That’s too big! Look around some!’ So I found a baritone (horn) and played in the marching band through high school, none of it with great proficiency!

“My first performance was with a rock band, playing electric bass, about 1971. I’d started playing folk music with friends, then worked into rock and roll, and played high school dances, that kind of stuff. I started getting into a little bit of jazz about ’72 or ’73, started to hear that kind of music and played with people. It was pretty rudimentary!

“My grandfather gave me a mandolin, and I had a girl friend who was into old-time and traditional music. I went to contra-dances and all that. She gave me a book of fiddle tunes and said, ‘learn these!’

“I was really impressed by the kind of flat-picking David Bromberg did at a concert at school in 1973, and I bought a guitar. After my second year in Philadelphia (at college) I took a year off and studied at Berklee college of music, studying electric bass. They teach everything from a jazz standpoint, jazz theory, a completely different program from what I’d had at Haverford with the classical approach. It was a valuable experience.

“I met someone into country and old-time music very heavily, and started playing mandolin with him, then started playing old-timey banjo that year, about 1975 or ’76. I played in the street in Boston that summer. I was also playing with Mandala, an international folk-dance ensemble, playing mostly bass. That was great! It was playing such a variety of music, mandolin and hammered dulcimer and trumpet. That was good, a lot of fun. That’s when I learned to buck dance—or clog. That decided me to major in music when I went back to Philadelphia to school. I was just having too much fun performing. The ham in me came out!

“In 1977-78 I played acoustic bass with a jazz band, traditional, with saxophone, drums, guitar, and bass. I could just keep up with it, and understood what was going on for the first time. About that time I met Bela, in 1977, at an old-time jam session.”

“Yeah,” Bela said. “Mark was playing wild (mandolin) and I was playing really traditional, so I got really wild and Mark’s eyes got real wide and his jaw dropped!”

“I didn’t get any respect for bluegrass until I started playing it,” Mark said. “There was an opening in a bluegrass band and I knew the banjo player (Bela). He didn’t know I played bass! I got the job, and that’s when Bela became a baritone singer!”

The band in question was Tasty Licks, which Mark joined in January of 1979, and played through the summer until the group disbanded, and he and Bela became half of Spectrum. Mark also recorded on Tasty Licks’ “Anchored To The Shore” and Bela’s “Crossing The Tracks.”

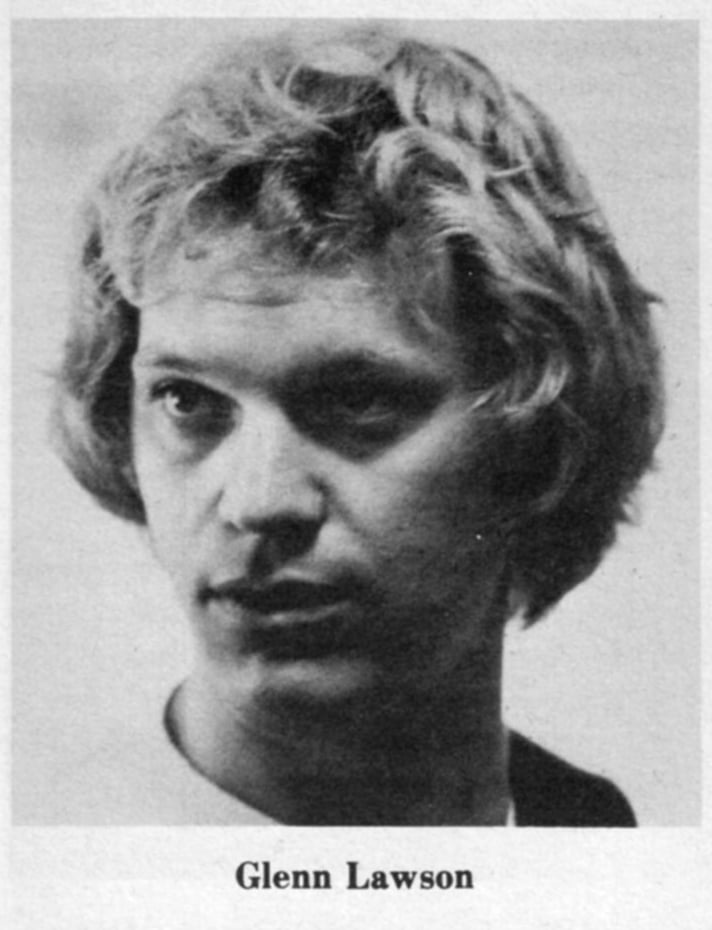

Balancing the urban, eastern influences of these three, guitarist Glenn Lawson, raised near Taylorsville, Kentucky, grew up in a family band tradition. “My family all played and sang and we played and sang together,” he said. “We lived on a 400 acre farm and I seldom saw outside of the farm until I got old enough to hitch hike!

“Family singing was a big thing with us, the most happy times I remember as a kid. The first banjo I ever saw my father took some cattle to Louisville and came back with an old folk-type banjo without a resonator, and we all played it.

“I started playing rock and roll when I was fourteen and instantly hated everything I had played before because I became “cool.” The band I was with lasted four years under different names, and we soon found out to make any money we had to go to top 40. At the end of four years we had a guitar player who wanted to go with gadgets—phase shifters etc.—and I hated it. I’ve always been into a smoother, slicker kind of sound.

“I left that band because I was outvoted three to one, and I bought a Martin guitar. I was going to play folk music, and then my brother brought home an Osborne Brothers record. Sonny Osborne just rung my chimes! They were my favorite band for a long time, until I started playing professionally myself!

“I still remember the chills! I’d never listened to bluegrass in depth and his (Sonny’s) banjo just hit me in the face, and the trios were just super-tight. It just seemed to be the way it should be done, and I just sat there and froze to death, listening to them.

“We’d done some trios (around home) and I decided that’s what I wanted to do. Two of my brothers and I formed a family band, and we’d do one set of bluegrass and one set of country. We played the Hardinsburg Jamboree in Hardinsburg, Indiana, and about 1969 or ’70 they booked in Jim and Jesse. We played and watched the show. They knocked me out, and I came to a realization that night that if I ever wanted to play professionally I’d have to leave the family band because the guys were all more interested in their jobs and families than they were in playing professionally.

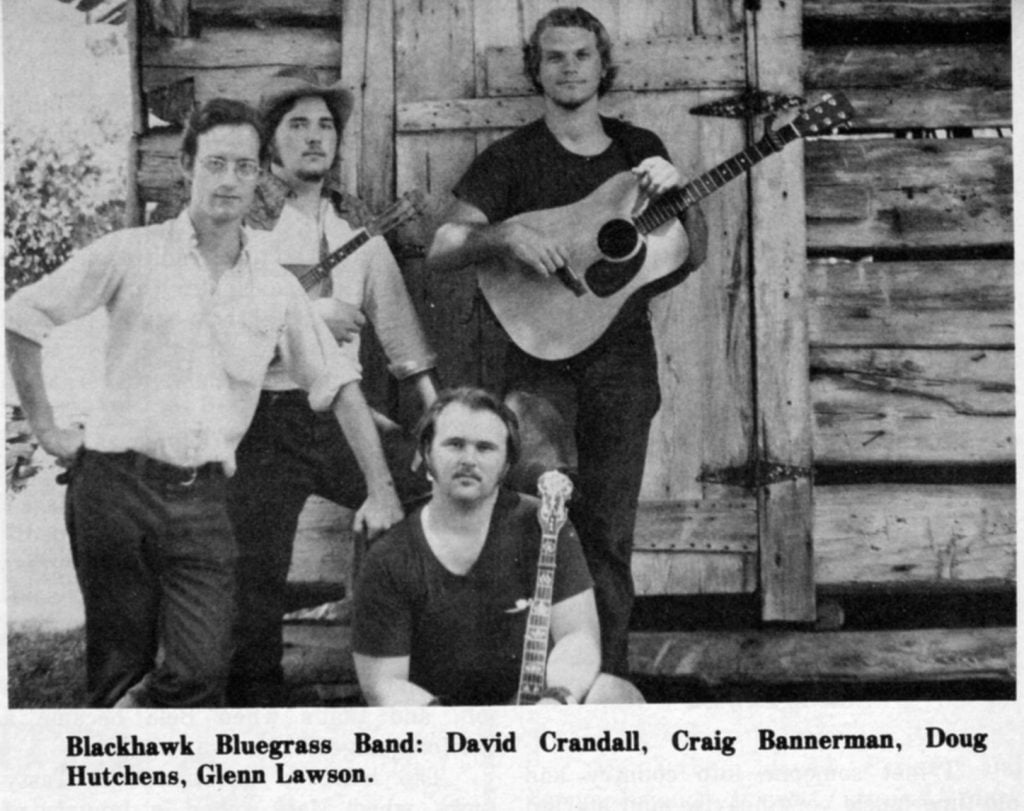

“I went to college shortly after that, and played the coffee house circuit, doing a single and duet with a girl. After that I got into a band with Doug Hutchens called The Phuzz Street Knuckle Busters (BU—April 1978). We made one 45 with a tune I wrote on one side and one he wrote on the other side. I was really amazed because he sent off the tape and it came back vinyl and I could give them to my friends and my mother! I played with Doug the last three years of college, then went back home and wanted to farm because I couldn’t see my way to get into music.

“Bun McClain called and told me Lonnie (Peerce) was re-forming the (Bluegrass) Alliance. Then he called Lonnie and told him I was available. I auditioned on bass in December of ’74, got the job, and then we couldn’t find a regular mandolin player, although Danny Jones played mandolin with us when we had a job. I started working on mandolin and ultimately played mandolin six months with the Alliance.

“I was sitting home one day in July (of 1975) and got a call from J.D. Crowe who asked me to come and audition. I said, ‘Come on, who is this?’ I got the job, and we rehearsed while I was still playing with the Alliance. There was Crowe, Harley Allen on guitar, Bobby Slone on bass, and me, on mandolin.

“J.D. really needs to be surrounded by players who are almost as competent as he is in order to bring out the best in him. That band would not have been a pickers band. I just couldn’t keep up on ‘Flint Hill Special’ on the mandolin. Given a year I could have, and the kind of man he was, he would have given me the year, but I wanted to play guitar.

“Harley was family oriented and wanted to play with his brothers, so I moved to guitar and played with J.D. for two and a half years, and that was the supreme learning experience of my life.

“I guess you kind of take things as steps. When you’re always working from behind you have to work all the time to get competent. It was difficult to work up to the point of competency.”

Glenn recorded with J.D. Crowe and The New South on “You Can Share My Blanket” (Rounder 0096.)

Since Glenn and Jimmy had played together, as well as Mark and Bela, the fusion of this group would have seemed a logical, immediate thing, but a lot of care and discussion went into its formation.

“We had a talk when Jimmy flew up to Boston,” Mark recalls. “We talked about what a show should be and the potentials. You try to get the biggest kind of vision you can. There was even talk of Las Vegas! Just trying to take a real wide view of what’s available.”

“Of a ‘show’ instead of a bunch of pickers!” Glenn added.

“We just had to find out what was realistic for the next few years,” Bela said. “Then it’s open.” “We talked about a mixed bag of tricks,” Glenn said. “Mark and Bela with, jazz, me with country and swing, and Jimmy one of the strongest performers in country and bluegrass.”

“We’ve been in existence since October of 1979,” said Jimmy. “In that time we’ve done a lot of experimenting to find out what’s going to work and what you can get away with.

“With a pickers band, everybody wants to play up to their full potential. We’re capable of over playing a song, putting more into it than it needs, but most of the music we play we try to play tastefully without going to extremes. Every now and then we’ll play numbers that do go to the extremes—some of the instrumentals, especially.

“There are certain audiences that really can appreciate your doing something like that, and others that don’t even suspect it.”

“We’re really audience oriented,” Glenn said. “We don’t go into a place and do what we want to and not care if the audience likes it or not. At a club like the Birchmere, which we feel is a very sophisticated audience, we pull our punches less than we would for a more tradition-oriented audience.

“If a musician doesn’t put himself on stage, the audience is going to know it. You can’t try to ‘cop’ a pulse which is unnatural to you.”

“That’s especially true in the music we play,” said Bela, “ ‘Cause we don’t play a mountain pulse. Natural is a good way to put it.”

“I feel you’re at your best when you feel a space to go into and a push from behind,” Mark said. “I’ve spent less time with the other instruments I play in order to spend more time with the bass because the music can afford the best I’m able to play. It’s a good feeling! You’re not being pushed aside, but being pushed along with the stream.”

“I,” said Glenn, “feel like I’ve peaked with this band. I feel somebody took a capo off my throat!”

“According to a few of the promoters we’ve played for, there were preconceived notions about this group,” Jimmy noted. “I’ve heard from bunches of people, ‘You didn’t sound nothing like I expected.’ ” “You can’t control preconceived notions,” Glenn said, “and you can’t control how you’re promoted. You just go out and play your licks and hope most of the audience leaves with a good impression.”

“Part of the joy of being an original member in a new band,” said Mark, “is that you’re a fourth of the sound, and you’re not filling in for anyone.”

“And part of the ambiguity in the beginning is that very same thing,” Bela remarked. “When you don’t have fifteen years of reputation, you don’t have fifteen years of experience.”

“We’re in the process of building our tradition right now,” Glenn stated.

“We’re free to go out and play what we want to,” said Jimmy. “Any established band that has ventured out of their field has rubbed their built-in audience the wrong way. We’re creating a reputation doing what we want to do.” With their first album due out almost any moment, and a summer’s worth of audiences whose preconceived notions, whatever they were, have been dispelled by actual performances, Spectrum’s future is clear: unusual music, thoughtfully chosen, carefully rehearsed, inventively played.

Whatever you call it, it works.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

This is a wonderful article about a tremendously influential group. Looking back forty-two years, there was a lot of good stuff going on in bluegrass music, and Spectrum was in the thick of it.

Thanks for reprinting it.