Home > Articles > The Archives > Pee Wee Lambert

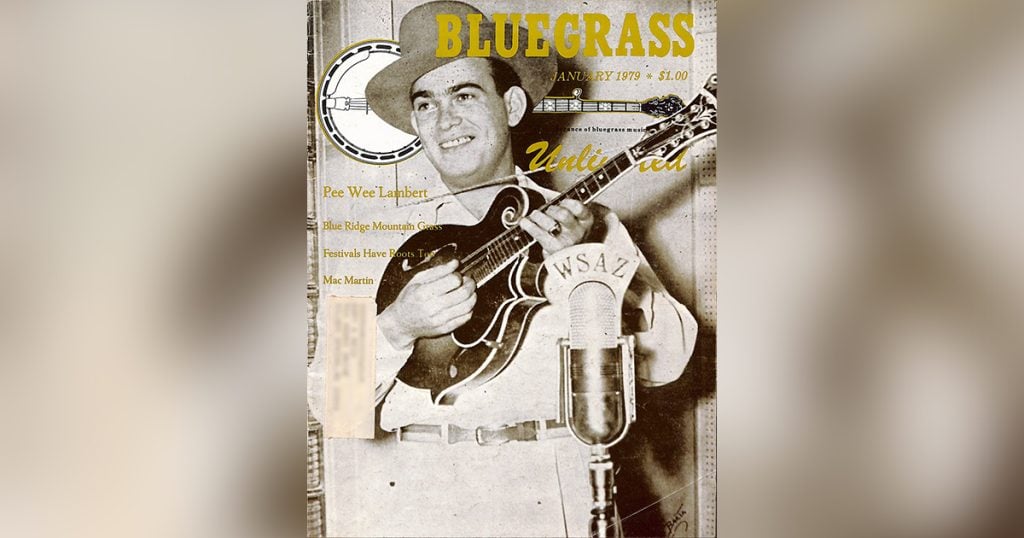

Pee Wee Lambert

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1979, Volume 13, Number 7

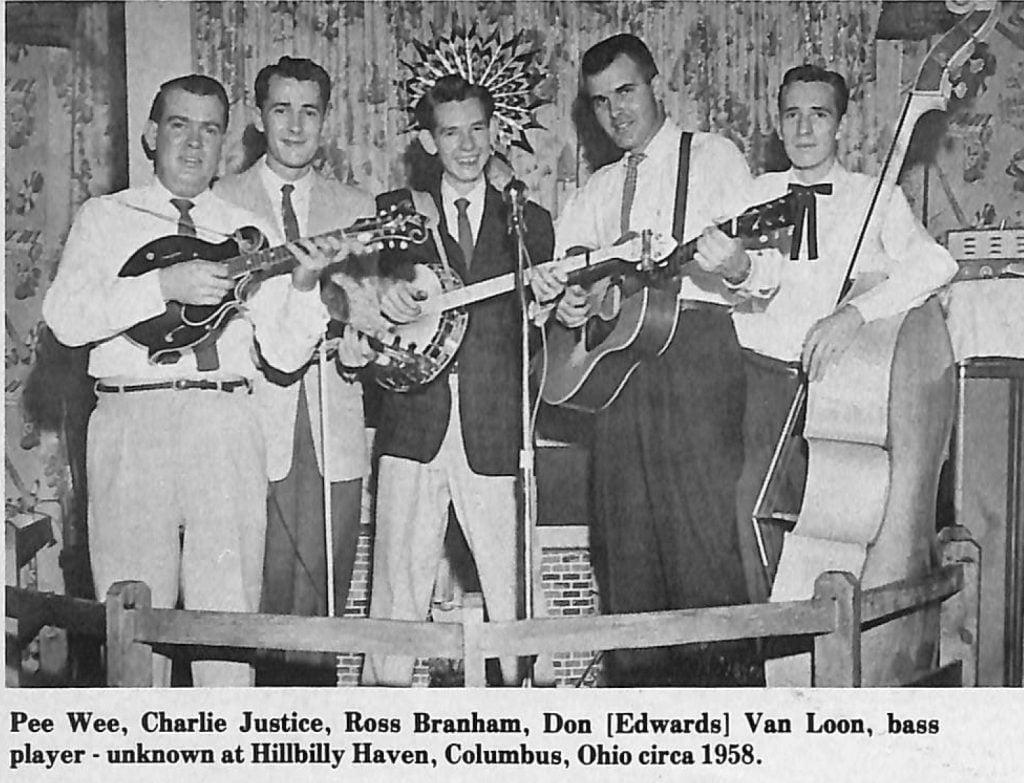

We were sitting in the nearly deserted back section of Chet’s bar in Columbus, Ohio, on a mild June night in 1965, having come early to get one of the few “good” seats in the place. The musicians had not yet begun to arrive and there were only a few of the most dedicated drinkers hunched over their glasses in the front of the place, safely away from the bandstand and anything that might divert their attention. The beer was, as usual, less than cold and that was the central theme of the conversation when the guitar player, a transplanted West Virginian named Landon Rowe, came in the back door. He waved as he opened the converted closet that served as a combination dressing and storage room for empty beer bottles and, having shed his coat and stowed his instrument, came to our booth and sat down.

“I guess you heard about Pee Wee,” he began.

We hadn’t, but judging from the tone of his voice the news could only be bad.

“He’s dead.”

We pressed for details but the only information Landon had was that Pee Wee Lambert had suffered a heart attack while on his way to work a week or so earlier.

Until about three months before he had been a regular member of the band he’d helped form with Landon, banjo player John Hickman and bassist Ray Willis; but now he was dead and it left a sadness in the local bluegrass community that was a long time in healing.

Slowly the other band members drifted in and soon it was time for the music to start. For those in the place who hadn’t heard, an announcement about Pee Wee was made after which the band sang “Gathering Flowers for the Master’s Bouquet.” It was perhaps not equal to the version recorded when Pee Wee was with Carter and Ralph Stanley but it was certainly no less heartfelt or sincere.

Pee Wee Lambert was a small man, no more than five-two or five-three, with a gleam in his deep blue eyes and the memory of him sitting in the back booth between sets drinking black coffee and talking about his days with the Stanley Brothers is something I will never forget. At the time it didn’t seem important or necessary to “interview” Pee Wee about his career—we were all just there, in a dingy tavern, some making music and some enjoying. Consequently, the stories he could have told and the facts he could have provided are missing, but with information gathered from people who knew, loved and played with him, combined with my own incomplete memory, a picture of the man and his importance in the history of bluegrass music begins to emerge.

In certain parts of the Appalachian Mountains there are dozens, even hundreds, of towns like Thacker, West Virginia, where in the early half of the twentieth century there wasn’t much to disturb the peace and quiet except the clamor of coal trains in and out of the mining areas. Darrell Lambert was born and grew up in Thacker but his life was to be shaped by events taking place far from the hills of Mingo County. Like many youngsters who entered their teens in the late 1930’s “Pee Wee” came heavily under the spell of the music of Bill Monroe. The Monroe Brothers were established artists during this period with recordings available all over the Southeastern United States. Undoubtedly Pee Wee had heard them as well as other mandolin-guitar duets and mountain string bands that included a mandolin player, but the greatest impact on his musical direction was made in 1939. Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys hit the air over WSM with the beginnings of a new, dynamic, driving music and Pee Wee Lambert, like hundreds of thousands since, was incurably and irrevocably hooked on a sound.

In 1939 and 1940 the people of the United States were becoming more and more aware that it was only a matter of time before they would be drawn into the war already being fought in Europe and Asia, but for a teen-aged mandolin player it is always one thing at a time and right then he was intent on music.

With a friend, Estil Dotson, from Thacker, Pee Wee started playing music locally until a chance encounter with fiddler Roy Sykes resulted in the formation of a band. “I met him hitchhiking one Saturday morning,” says Sykes of their first meeting. “He had a mandolin so I stopped and picked him up. Pee Wee and Estil Dotson, a guitar player from Thacker, had been playing together some…(We) went to Bristol to play…on WOPI. (It) was the only station down there then; that was before WCYB.”

And what kind of music was Pee Wee playing then? According to Sykes, “He was a duplicate to (Bill) Monroe. There’s some that can play the mandolin…and some that have the high voice…but Pee Wee could do both.”

This association lasted approximately three years until Sykes and Dotson moved to Baltimore in anticipation of being called into the Army in 1942. Pee Wee stayed behind in West Virginia, entering the Army Air Corps some time later, probably in late 1942 or early 1943, and serving two and a half years in the China-Burma-India Theatre. While with the Air Corps he played in several part- time bands before being discharged in December of 1945.

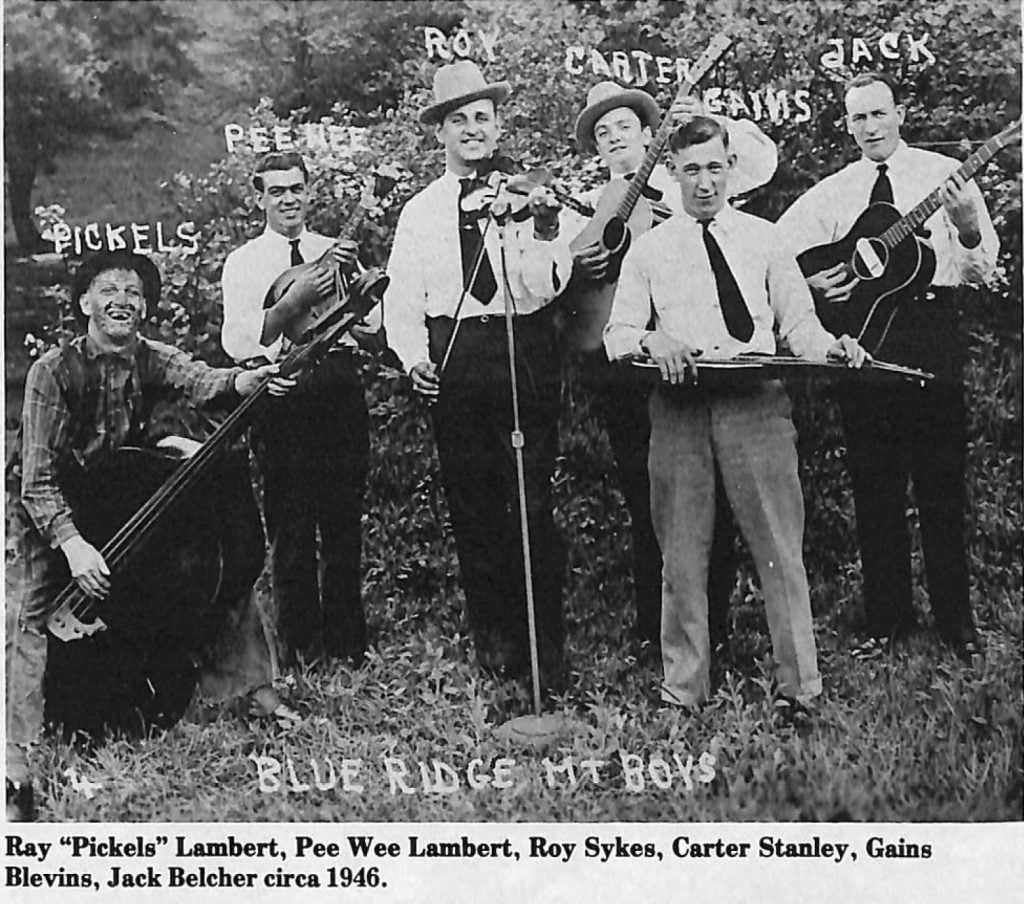

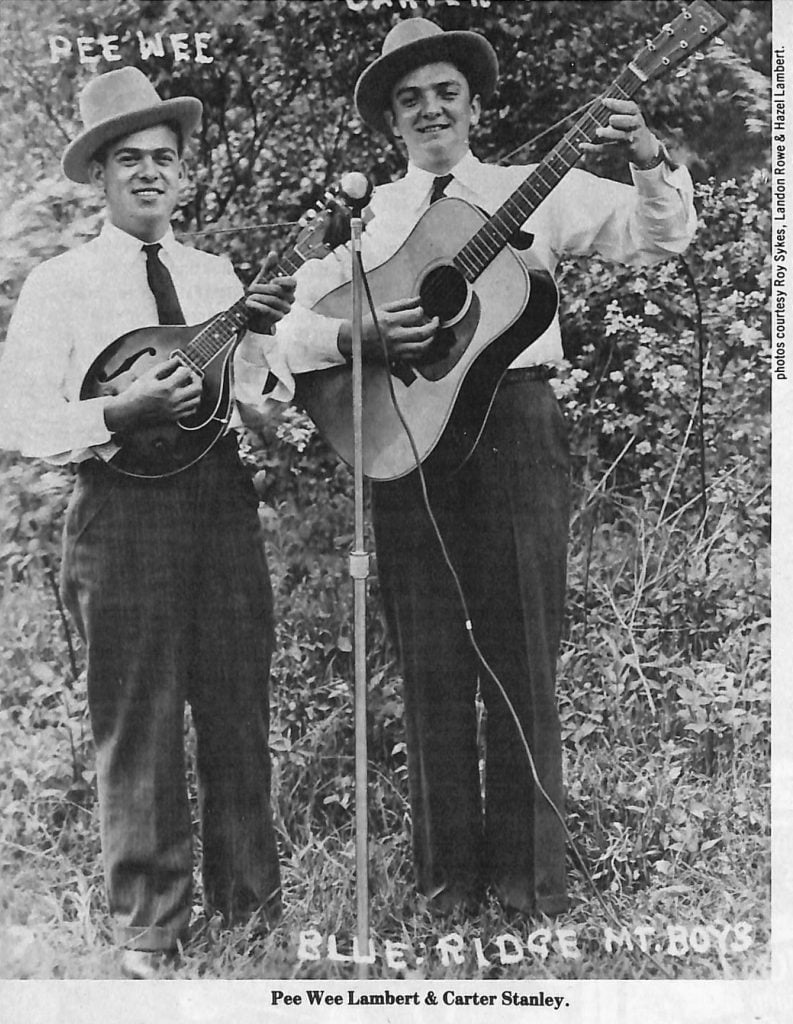

In early 1946 Roy Sykes was also discharged from the service along with another young Virginian by the name of Carter Stanley whom he’d met while mustering out at Ft. Meade, Maryland. Sykes, on returning home, was eager to put his band back in operation and since Carter lived fairly near it was a natural move for them to get together. Shortly a country band was performing over WNVA in Norton, Virginia, featuring music played in a variety of styles. In addition to Sykes on fiddle and Carter Stanley on guitar, Pee Wee Lambert was recruited to resume his pre-war role as mandolin player in the band. The rest of the Blue Ridge Mountain Boys were Ray “Pickles” Lambert (no relation) on bass, Gaines Blevins on steel guitar, J.D. Richards on guitar and Jack Belcher on electric Spanish guitar. It was Sykes’ intention to put on a complete show with fiddling, ballads, comedy, new country songs and old-time singing using Norton as a home base with performances in the surrounding counties. Because of their particular interests and abilities it fell upon Carter and Pee Wee to do the old-time-brother-singing portion of the program thereby establishing a duet (Pee Wee singing tenor to Carter’s lead) that would continue even after the formation of the Clinch Mountain Boys.

In the fall of 1946 Ralph Stanley returned to Virginia from military service and was taken into the band by Sykes. “I played with Roy about three weeks,” Ralph remembers after which the Brothers and Pee Wee decided that the course of their music should take a direction different from that of the Blue Ridge Mountain Boys and they set about to organize their own band. With fiddler Bobby Sumner they began performing as the Clinch Mountain Boys around the first of December, 1946.

“We started first on the same station where they were playing with Roy Sykes, on WNVA in Norton. I believe we worked there a little less than thirty days.”

In early 1947 the Stanley Brothers and the Clinch Mountain Boys auditioned for and won a spot on a new radio station, the now legendary WCYB. According to Ralph, “We moved to Bristol, Virginia/Tennessee, and started a program there known as ‘Farm and Fun Time’. And we worked that program about an hour, from 12:05 till 1:00 o’clock. We worked that hour by ourselves (at first). Later on some more groups joined in and they extended it to two hours.”

(WCYB in the late 40’s and early 50’s was the home station for many of the early greats in bluegrass. In addition to the Stanley Brothers, Flatt and Scruggs, Mac Wiseman, and the Sauceman Brothers, among others, were based there.)

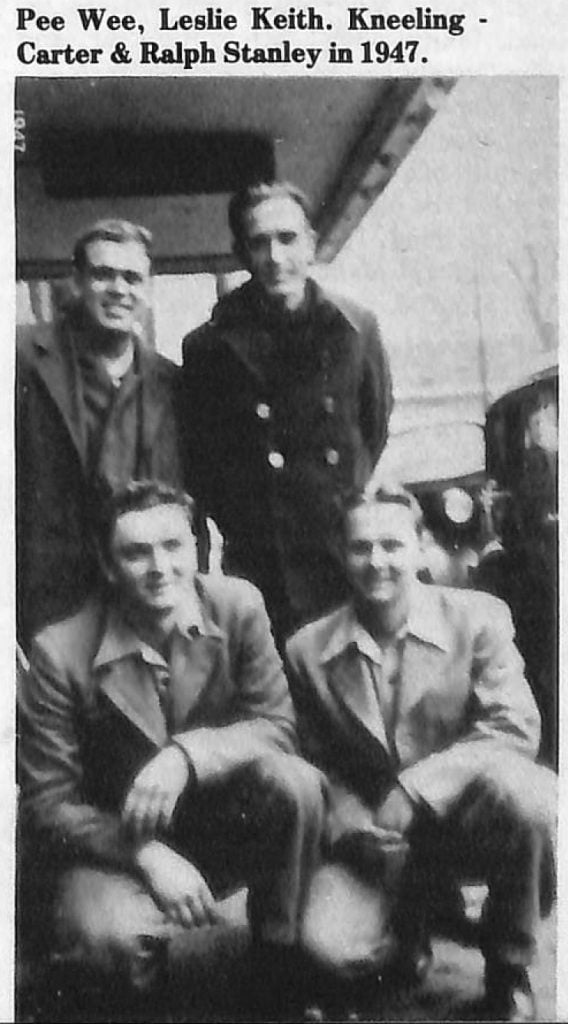

By this time the Stanley Brothers had acquired the services of veteran fiddler, the late Leslie Keith, who recalled that during this period Pee Wee sang the tenor while Ralph contributed the baritone and he (Keith) sang bass on the gospel songs. (See “Leslie Keith: Black Mountain Odyssey” by Bob Sayers, BU, December, 1976.)

Natural reticence on Ralph’s part is probably the reason he did not assume more tenor duties at this point. As he tells it, “Carter and Pee Wee were singing all the duets when I came back (from the service) and they continued to sing part of them (although) I would sing some with Carter. I was pretty backward at that time. I liked to stand back and let somebody else do a lot (of the singing).”

It is significant that the Carter/Pee Wee duets were continued during this early period as Pee Wee became more and more influenced by the music and aura of Bill Monroe. A lot had changed between the time he went to war and the time he returned home. With the addition of Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs to the Blue Grass Boys, Monroe’s music had crystalized, taking new depth and power, and the effects were not lost on Pee Wee.

While Ralph and Carter based much of their music on the old forms and archaic sounds of the mountains, Pee Wee brought the direct influence of Bill Monroe into the band. His high lonesome singing and bluesy mandolin playing, derived from Monroe, yet different and recognizably his own, gave to the Stanley Brothers a decided “bluegrass” sound although it would be years before that term would come into use.

About Pee Wee’s effect on their music Ralph says, “When Pee Wee was with us we had a sound (that) resembled Bill Monroe a little bit. Pee Wee sung a lot like Bill did. His idol was Bill Monroe and he played a lot like Bill with the exception (that) he played it, I think, a little bit straighter than Bill at times. He got a lot of things from Bill but he developed it more or less into a style of his own.”

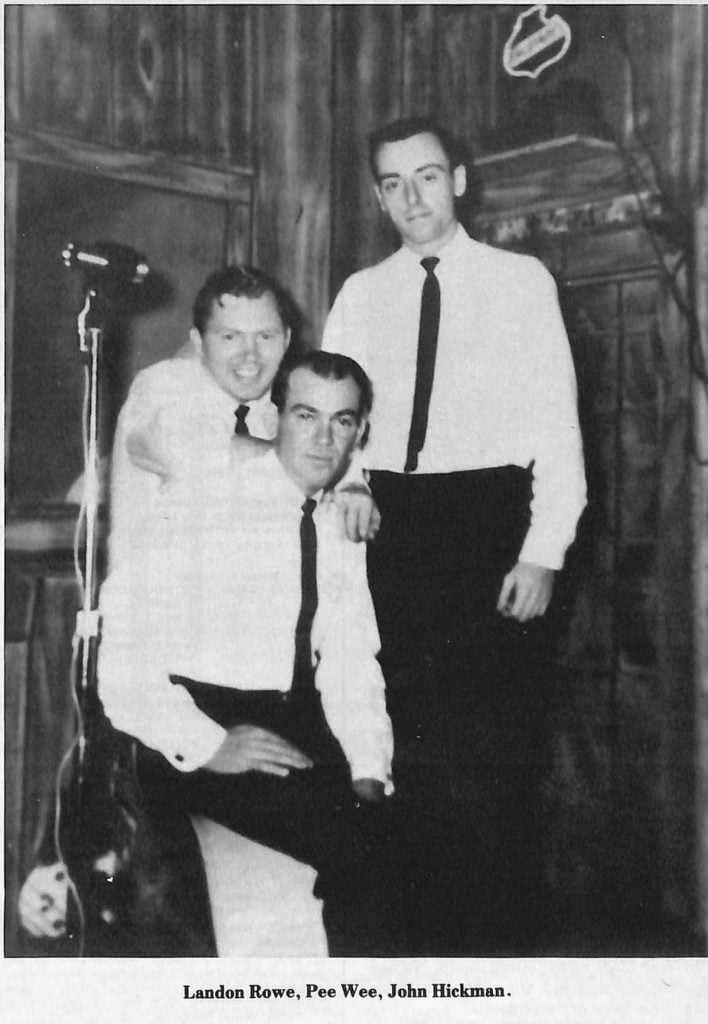

Between September 1947 and June 1949 the Stanley Brothers recorded ten sides for the Rich-R-Tone company of Johnson City, Tennessee, beginning with “Mother No Longer Awaits Me At Home” and including such classic titles as “Little Glass Of Wine,” “Little Maggie” and “The Girl Behind The Bar.”

From those recordings one is of particular interest-Rich-R-Tone #418, “Molly and Tenbrooks”/“The Rambler’s Blues.” Bill Monroe had been featuring “Molly and Tenbrooks” on the radio and in person with considerable success but in mid-1948 his recording, made in October of 1947 had not yet been issued. Because of Pee Wee’s appreciation for Monroe’s live performance of the song and sensing the tremendous public response it was receiving, the Stanley Brothers incorporated it into their show and recorded it shortly thereafter. With Ralph picking solid three finger banjo and Pee Wee putting all the spirit and fire he could into the singing, the result was a highly saleable item that was released in September of 1948, a full year before Monroe’s version came out. In addition to being a clever marketing coup it was also a statement of stylistic indebtedness which some scholars consider to be one of the earliest indications that the sound of Monroe’s music was developing into a fullblown style.

(According to Neil Rosenberg, writing in Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys, an Illustrated Discography, at that time Monroe viewed the Stanley Brothers’ adopting his style and material with some displeasure, feeling perhaps that they represented a challenge to his position in the market place. Ultimately this resulted in Monroe’s leaving Columbia Records when that label added the Stanleys to its roster. Additional information of the beginnings of bluegrass can be found in “From Sound to Style, the Emergence of Bluegrass” by Neil Rosenberg, BU, January, 1969.)

But for many followers of the Stanley Brothers it is the next step in their evolution that is the most exciting and it is a development in which Pee Wee Lambert played a significant role.

In 1949 and 1950 they recorded for Columbia Records some of the most hauntingly beautiful songs ever done in bluegrass. The emphasis in these sessions was on singing with very little in the way of fancy picking. Rather, the accompaniment was subdued and restraint was exercised every step of the way to insure that nothing would distract the listener from the voices blending in a new way.

Ralph Stanley recalls, “We found a trio with Carter, Pee Wee and myself and it was a new style for this type of music. Carter sang the lead and I sung a regular tenor and Pee Wee got what’s known as a high baritone. And to my knowledge that was the first trio of that type to be sung.” There were also duets and solos recorded during this period and the influence of Bill Monroe still lingered in songs like the Carter/Pee Wee duets, “The Old Home,” “Hey, Hey, Hey” and “Let Me Be Your Friend,” the latter being very much like Monroe’s own “It’s Mighty Dark To Travel,” but it is the trios for which these sessions are particularly remembered.

Songs like “A Vision Of Mother,” “White Dove,” “Drunkard’s Hell,” and the exquisite “Lonesome River” with the crystal-clear high baritone of Pee Wee Lambert on top, made it abundantly clear that there was now a definite Stanley Brothers sound within the as-yet-unnamed bluegrass style.

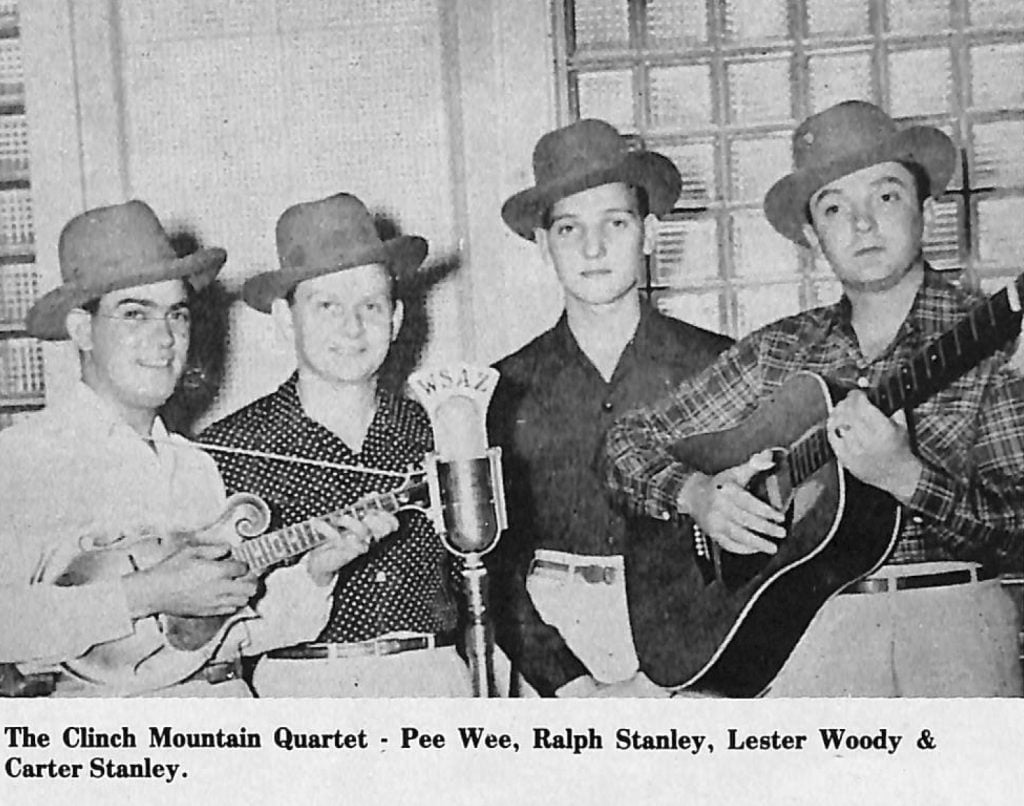

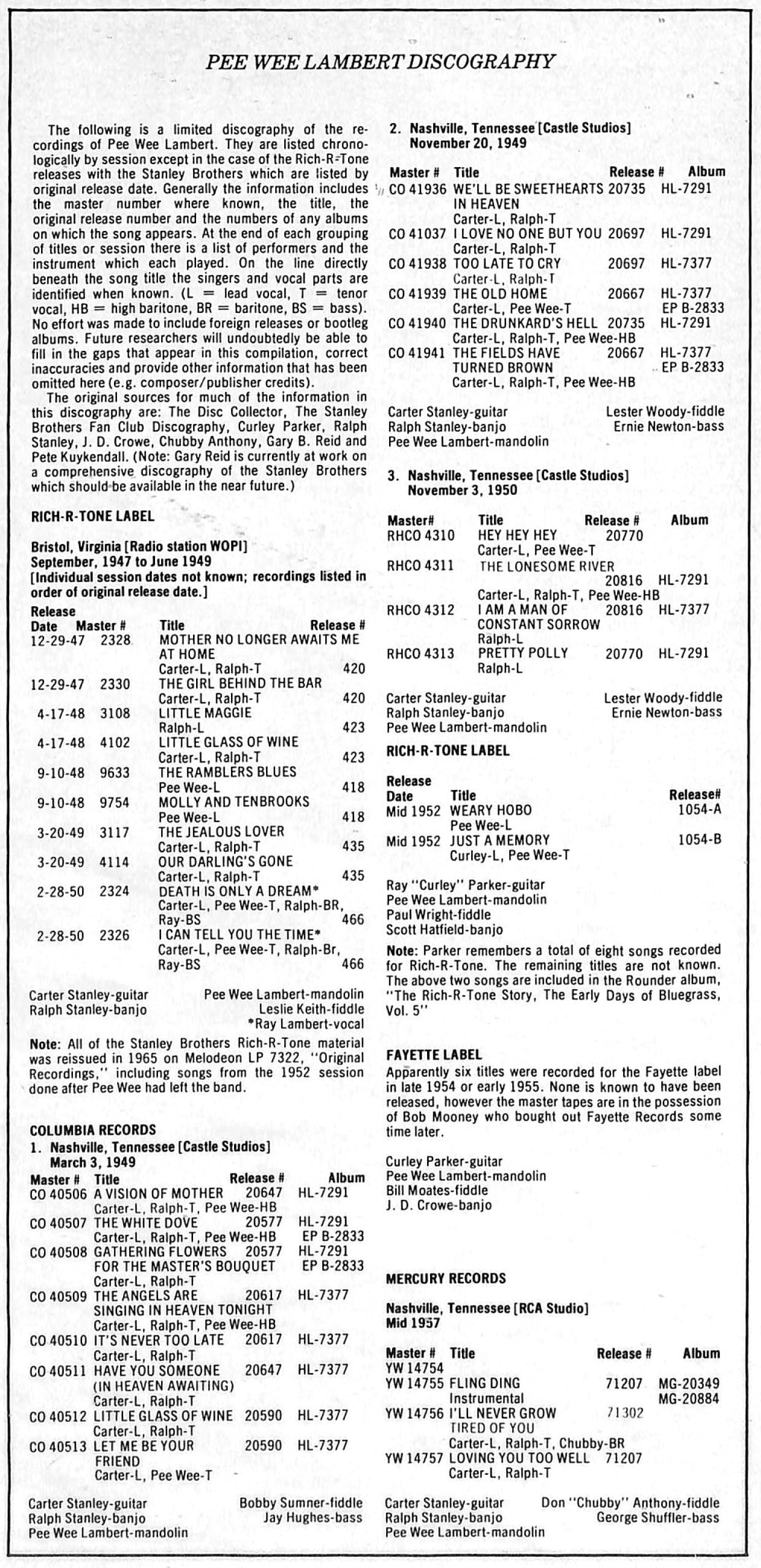

The year 1950 found the Stanley Brothers doing quite well. They had moved from the comparative obscurity of Rich-R-Tone to a major recording company—Columbia—and their following had increased considerably as a result of regular appearances throughout the region on radio stations like WCYB in Bristol and WPTF in Raleigh. They were also beginning an involvement with television at WSAZ in Huntington, West Virginia. However, in spite of their apparent good fortune, the Clinch Mountain Boys decided in early 1950 to disband and pursue a more conventional life style, at least for a while.

Of that point in their career Ralph says, “It was sometime after we’d been playing, maybe three years, that we decided to quit one winter. Carter and Pee Wee worked at the sawmill my daddy and two brothers had (and) we farmed a little bit.”

The early months of that year, then, were spent in relative inactivity musically until the return of warm weather at which time the Stanley Brothers went back on the road. This time their activities continued through the first quarter of 1951 with a schedule that included what turned out to be Pee Wee’s last recording session with them for the Columbia label; but by Spring they had disbanded again, with Carter moving to Nashville to fill the guitar-player/lead-singer vacancy in Bill Monroe’s band. In the meantime Ralph and Pee Wee remained uninvolved with any professional playing. Later in the year, however, Ralph was called on several times to fill in with the Blue Grass Boys during the absence of Monroe’s usual banjo player of that period.

“I played a few dates with Bill in the Fall of ’51 when Rudy Lyle had to go in the service, I believe.” It was while returing from one of those shows that Ralph was injured seriously in an automobile accident. “Pee Wee was driving the car. He’d gone along as a guest and we had the wreck coming home.”

With Ralph unable to play and Carter still with Bill Monroe, the future of the Stanley Brothers as a performing unit was even more uncertain in late 1951 than before. At this point Pee Wee’s career took a turn that duplicates the experience of countless numbers of other young musicians. He had been a full-time professional performer through most of his twenties but with a growing family and his thirties approaching, it became apparent that a more secure way of life might not be a bad idea. At the same time he did not want to give up music entirely. Conveniently, then, guitarist/fiddler Ray “Curly” Parker entered the picture. “When I first met Pee Wee he was in Norton, Virginia,” recalls Parker, “I believe Carter was with Monroe at the time.”

Parker was a registered surveyor involved in construction work in Kentucky, West Virginia and Ohio, while playing music as an avocation. This meeting provided Pee Wee with the opportunity for regular employment without having to give up performing.

The circumstances were ideal and the two wasted no time in forming a band; an item in a December, 1951 issue of Billboard magazine notes that the Pine Ridge Boys led by Curly Parker and Pee Wee Lambert, “formerly with the Stanley Brothers,” were beginning a radio program over WHTN in Huntington, West Virginia.

At about this same time Ralph Stanley was recovering from his injuries and he and Carter were making plans to begin working again. According to Hazel Lambert, Pee Wee’s widow,“Ralph and Carter went to Russell (Kentucky) and got Pee Wee and they went to Lexington.” (Both WVLK in nearby Versailles, Kentucky, and WLAP in Lexington featured live country music during the early 1950’s. Flatt and Scruggs and Jim and Jesse, among others, made regular appearances.)

This time he only stayed with them a short while and “in the early part of 1952 we moved to Russell to work with Curly Parker who was a civil engineer and also a musician. We were in Russell for five years and (during that time) they just played on the side.”

For part-time pickers they were a very active band with regular radio shows and personal appearances throughout the area and song-book/picture-albums to sell at those engagements. Other members of the group for much of this period were Scott Hatfield on banjo, Bob Tincher on bass and Bill Moates on fiddle.

“Pee Wee and I were working and playing all through Virginia, North Carolina and all in this part of Kentucky and over in Ohio. We played school houses, theaters and we had radio shows on WHTN in the morning and WIRO (Ironton, Ohio) in the evening.” As with many country bands of the period the need to make records does not seem to have been very important to the Pine Ridge Boys for during their five years together only one single record is known to have been released from their two recording sessions.

(Neil Rosenberg suggests in Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys, an Illustrated Discography, that Monroe, in particular, considered himself an “in person” performer rather than a recording artist, and the same might be said about many other country musicians of the day, including Curly Parker and Pee Wee Lambert. They did not depend on record sales to build their audience, relying more on radio shows and personal appearances to maintain their popularity. Further comments by Curly Parker on the subject can be found in the notes accompanying Rounder LP 1017, “Early Days of Bluegrass, Vol. 5”.)

Their first session was in mid-1952 for Rich-R-Tone where, five years before. Pee Wee had made his initial recordings with the Stanley Brothers. The record released was “Weary Hobo,” sung by Pee Wee, backed by “Just a Memory” which was a duet with Curly Parker singing lead. Fiddler Paul Wright, a distant cousin of Ricky Skaggs, substituted for Moates on these cuts.

Parker remembers the sound of the band as initially having considerable similarity to the Stanley Brothers but as they grew more accustomed to one another and farther removed in time from Pee Wee’s involvement with the Stanleys they gradually adopted a style more like Bill Monroe. This can be borne out by comparing the Rich-R-Tone release, which was recorded fairly early in their association, with tape recordings of later radio shows.

In 1953 or 1954 construction work took Curly Parker and his crew, including Pee Wee Lambert and the rest of the band, to Springfield, Ohio where they lost no time in lining up a radio slot at station WJEL. It was also about this time that, according to Parker, “We changed the name to the Bluegrass Partners; the Pine Ridge Boys just didn’t sound like a bluegrass band.” (This may be one of the earliest indications that the word “bluegrass” was coming into use to identify a particular kind of country music.)

But in the Spring, Scott Hatfield had an opportunity for some other enterprise and the group was soon in need of another banjo player. Hazel Lambert remembers the change-over, “That’s when they got that little red-headed J.D. Crowe.”

Parker went to Kentucky and after promising not to encourage him to drink beer was allowed by J.D.’s parents to take their 16-year-old banjo picker back to Ohio. “I went with them in 1954, during summer vacation. They were building an airport in Springfield and Curly was involved with laying out the runways or something and we’d work all day on that project then we’d pick on the side,” says J.D. of his first professional experience.

Most of their playing during this period was done in clubs, jamboree type shows, and on the radio, with extra money brought in by selling songbooks and pictures. At this particular time the group had no records to sell and still felt no compelling need to have them since they all made good money on their day jobs and the musical performances were extra and done as much for fun as profit.

When their work in Springfield was completed the group returned to Russell, Kentucky, where they continued the same pattern of construction work for a living and picking as a sideline with a new radio show, this time on WTCR in Ashland, Kentucky. After their return they decided to journey to Lexington to make some recordings for the Fayette label.

J.D. remembers that “…we cut them in Bill Hunley’s basement. He owned the Two Keys Restaurant and had this recording studio at home.” Unfortunately, the recordings are not known to have been released. (The Fayette label was later sold to Bob Mooney, who operated REM records until 1966. In discussing the session with Mooney it was learned that the master tapes are still in his possession although he does not have a log of individual titles. He did, however, express a willingness to co-operate with anyone interested in releasing them.)

In 1955 J.D. returned home, later to work briefly with Mac Wiseman before joining Jimmy Martin in 1956. But his tenure with the Bluegrass Partners gave him his first real taste of the professional music world and the impressions made by Pee Wee Lambert can be seen and heard in his music and performances from that point on.

“(Pee Wee) showed me that it doesn’t matter how much you can pick, if you don’t have your singing and timing you don’t have anything. He was a real pro (who) knew how to do it right. I learned the way to do it from him.” The life of a road musician on the school-house drive-in theater-small-town-radio- station circuit in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s was not easy. A grueling cycle of playing, grabbing a bite to eat and long hours in the car swapping driving chores so everyone would get a chance at a few hours sleep before playing again was not uncommon but Pee Wee, as well as hundreds of his contemporaries, survived, even thrived, on the grind, honing his skills and refining his art in that “golden age” of bluegrass.

The mid-1950’s, however, saw the emergence of rock and roll and the changing patterns of popular musical taste that resulted put many traditional country groups out of business entirely. Those who stayed with it were forced either to change their style, to suffer with reduced bookings or to seek a new outlet, and for many that outlet became the bars and taverns of Northern industrial cities. Here they performed for the growing numbers of Appalachian immigrants who came north in the post-World-War-II years looking for jobs but finding also a kind of urban estrangement that led many of them to seek relief in the places that featured the music and faces from “down home” and where a sense of dignity and worth could be rekindled at least temporarily. After his work took him to Columbus, Ohio, in 1957, Pee Wee was quite active in that area’s local bluegrass scene.

Banjo player Roosevelt “Ross” Branham was a mainstay in bluegrass around Columbus after leaving Kentucky in 1953 and he remembers local activity that included several “clubs.” He had met Pee Wee around 1950 or 1951 and when he (Pee Wee) arrived in Columbus it was inevitable that their paths should cross again.

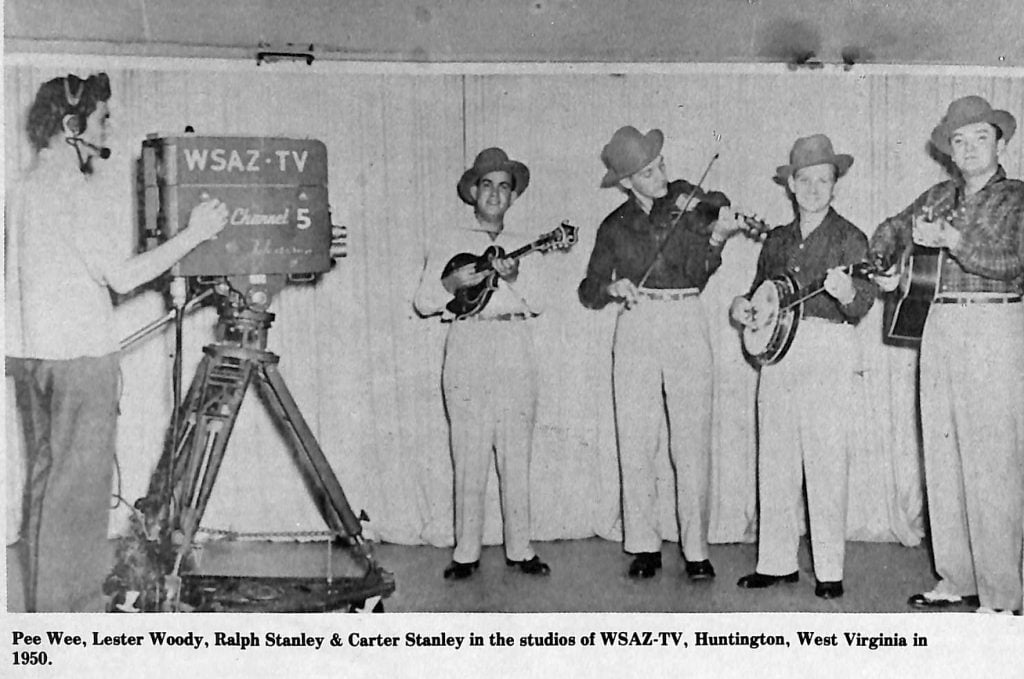

Most of the bar picking of that period centered around a place called variously “The Family Inn,” “The Golden Nugget” or, most appropriately, “Hillbilly Haven.” Curly Parker played there a few times with Pee Wee and, until it was replaced by an expressway, it hosted nearly all of the area’s pickers as well as occasional nearby groups such as the Osborne Brothers and Red Allen. But in 1957 a typical band would include Ross on banjo, Pee Wee on mandolin, Charlie Justice on fiddle, and Don (Edwards) Van Loon on guitar with one of several bass players likely to be on hand.

Shortly after Pee Wee became established in Columbus he was appearing at the “Stop 40” club on East Main Street with Ross, Dobroist Danny Milhon and bass player Chuck Cordle when he received a call from the Stanley Brothers to help them with a session on the Mercury label and in mid-1957 he went to Nashville where he made his final recordings. Titles from that session include “Fling Ding,” “I’ll Never Grow Tired of You” and “Loving You Too Well.”

Fiddler “Chubby” Anthony, who participated in this session, is outspoken in his praise for the music of Pee Wee Lambert. “I feel like Pee Wee was as responsible for the Stanley sound the way it was back then as Carter and Ralph were. To me that was their best music. After Pee Wee left they had some great bands but I don’t think they ever came close to that original sound.”

If the information about this particular period seems a bit scant there is a very good reason. As anyone who has done much bar picking will attest, after a while it all seems to run together in the mind; pickers come and go and guests sit in and the locations change but in looking back it all seems like one long Saturday night and, except for some special event like the last Stanley session, it becomes impossible and almost unnecessary even to try to sort it all out. It is enough to say that this was a time of good music played with energy and enthusiasm by some of Columbus’ finest musicians.

But the strain of picking in bars week after week could affect the health of even the strongest men and by 1959 or 1960 Pee Wee had decided to give up playing completely. He sold his mandolin and retired to a regular life of construction work, part-time clerking at a neighborhood grocery, raising his children and enjoying family life in general.

For the next four and a half years Pee Wee was totally inactive as far as music was concerned. There were opportunities to resume playing but he steadfastly declined all pleas that he join up with another group; he was “retired” and liked it that way.

Nevertheless, early in 1964 he was approached by guitarist Landon Rowe who hoped to get him to start a band with banjo player John Hickman who had just returned home from the service. John, by then a local legend on the banjo, had been a promising teenager at the time of Pee Wee’s retirement. Landon was a longtime admirer of Pee Wee’s work whose memory for songs was (and still is) phenomenal. Perhaps this combination seemed too good to pass up for, by Spring of 1964, Pee Wee was back in harness.

One of the reasons that may have contributed to Pee Wee’s decision to quit playing before was the fact that his voice wasn’t holding up. “The mandolin playing was still there,” says Ross Branham, “but his voice was about gone. He couldn’t get the high notes any more.” This is interesting because among the strongest recollections of those who heard Pee Wee during 1964 and 1965 was his remarkable vocal power, both as a tenor and a solo singer.

As bassist Ray Wills, who played with him during that last year or so, puts it, “He had so much power that he could stand at the back of the stage and still be heard over everybody else.” Perhaps the time off had restored something to his voice.

For approximately the next year the stages from which Pee Wee’s power could be heard were, once again, located in taverns around central Ohio. Until June, 1964, they played in West Jefferson, Ohio, at a place called the Gator Inn. From there they moved to the Country Room on North High Street in Columbus, finally settling in farther up North High at Chet’s Bar in January, 1965.

As with most bar bands of this period their repertoire consisted almost entirely of standard material from the big-name bluegrass performers. Some country songs were worked out as were new bluegrass releases as they became available but there was little emphasis on original material. The strengths of the band were based on superior performances of the basic bluegrass of Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers and others. As in the past, Pee Wee still showed considerable feeling and respect for Bill Monroe. Many of the songs that he featured were those of Monroe’s that allowed him to reach out for the sky-high tenor notes that local followers expected of him. Songs that come to mind particularly are “White House Blues,” “It’s Mighty Dark To Travel,” “Girl in the Blue Velvet Band” and, of course, “Molly and Tenbrooks” to list only a few.

Curiously they seldom, if ever, featured any of the trios which Pee Wee had helped develop with the Stanley Brothers over a decade earlier. The general mood of a neighborhood tavern on a weekend night could not be described as conducive to those quietly introspective masterpieces and undoubtedly that is part of the reason why they weren’t attempted.

While taverns provided the primary employment for the group they also pursued other outlets, appearing on Gene Carroll’s Sunday afternoon jamboree over WDLR, Delaware/Marysville, Ohio, early in 1965, as well as at private gatherings from time to time.

Bar picking has always been an uncertain kind of endeavor, particularly during periods when bluegrass wasn’t overly popular, and bar bands had a way of changing personnel from time to time while still continuing the same basic feeling. So it wasn’t a big surprise in March of 1965 when we found a different mandolin player in the band at Chet’s. Evidently it simply wasn’t convenient for Pee Wee to play that night and he’d be back when he could work it out; but as the next few weeks went by it became apparent that Ralph “Robby” Robinson was now the full-time mandolin picker. Pee Wee must have retired again. No one seemed worried but three months later Pee Wee Lambert was dead.

Born August 5, 1924, Pee Wee died on June 25,1965, a little over a month before his forty-first birthday. Ironically, it was only two months later, on Cantrell’s horse farm near Fincastle, Virginia, that Carlton Haney’s first bluegrass festival was held signaling the renewal of interest in the music that had been forced out of the mainstream a decade earlier.

Although today his name is relatively unknown to many bluegrass followers and pickers, those with whom he played or who heard him perform will never forget his impact. By virtue of his monumental contribution to the early sound of the Stanley Brothers and his influence, that even now continues to shape knowledgeable young musicians and seasoned professionals alike, Pee Wee Lambert is considered one of the giants in the history of bluegrass music.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Great article. I remember so well hearing the marvelous trios on Columbia with the Stanley Brothers.

Thanks for this article tying so many musical threads together. Those “high baritone” trios are as distinctive a part of the Stanley sound as Bobby’s “high lead” was to the Osborne brothers.