Home > Articles > The Tradition > Music In American Life Series

Music In American Life Series

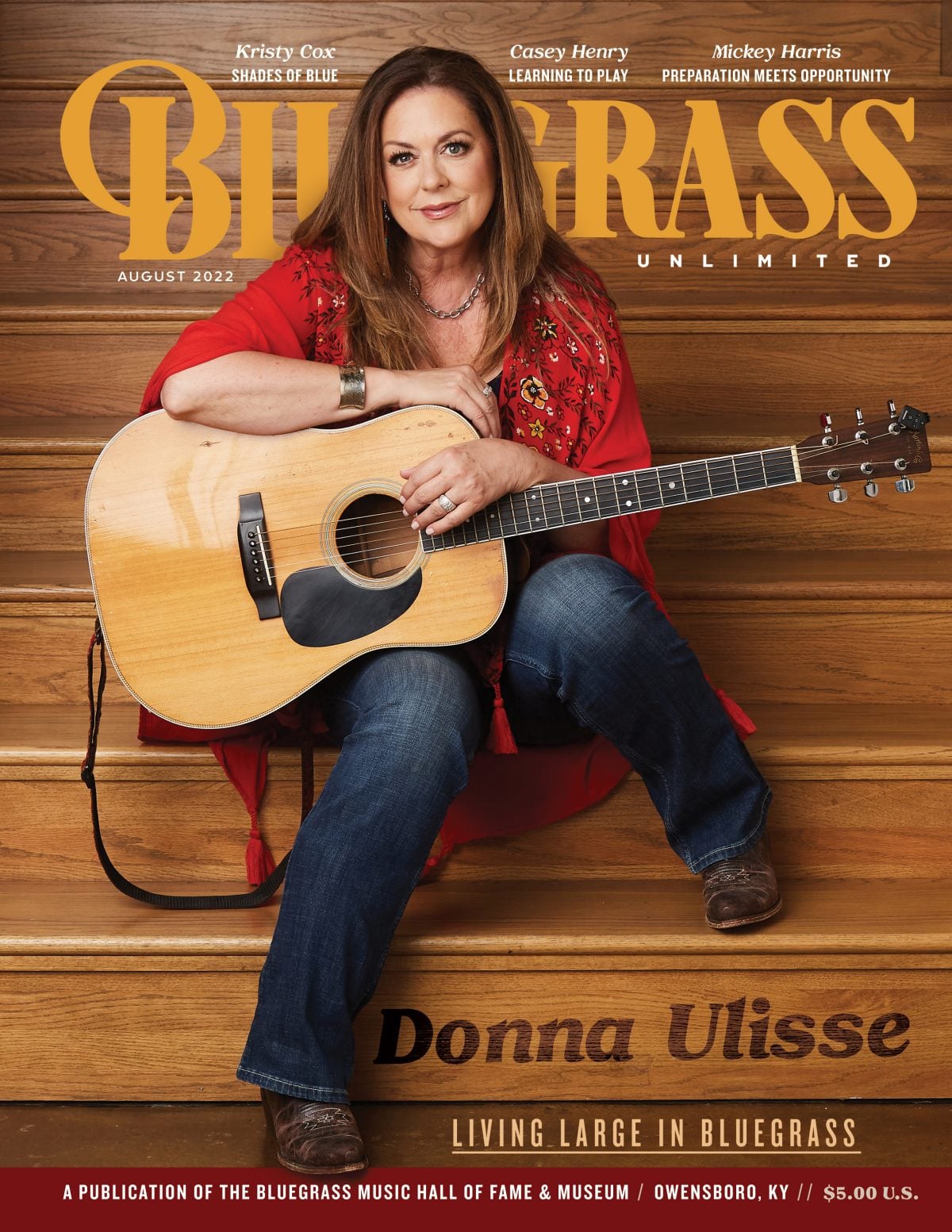

I’ll have to confess that the first record album that I owned was not a bluegrass album. I was a suburban kid listening to rock radio in the 1960s and my first album was Paul Revere and the Raiders Spirit of ’67. When I got the album, I not only listened to the music over and over, I read every word of the liner notes many times. Even at a young age, I was eager to learn everything that I could about the musicians that I was listening to on my record albums. I felt like it somehow connected me to the music on a deeper level. When I started listening to bluegrass music in the late 1970s, it was the same. I wanted to know everything about Earl Scruggs, Lester Flatt, Bill Monroe, Jimmy Martin and the Stanley Brothers. Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine became my best friend and, over the years, so has the University of Illinois Press.I’ll have to confess that the first record album that I owned was not a bluegrass album. I was a suburban kid listening to rock radio in the 1960s and my first album was Paul Revere and the Raiders Spirit of ’67. When I got the album, I not only listened to the music over and over, I read every word of the liner notes many times. Even at a young age, I was eager to learn everything that I could about the musicians that I was listening to on my record albums. I felt like it somehow connected me to the music on a deeper level. When I started listening to bluegrass music in the late 1970s, it was the same. I wanted to know everything about Earl Scruggs, Lester Flatt, Bill Monroe, Jimmy Martin and the Stanley Brothers. Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine became my best friend and, over the years, so has the University of Illinois Press.

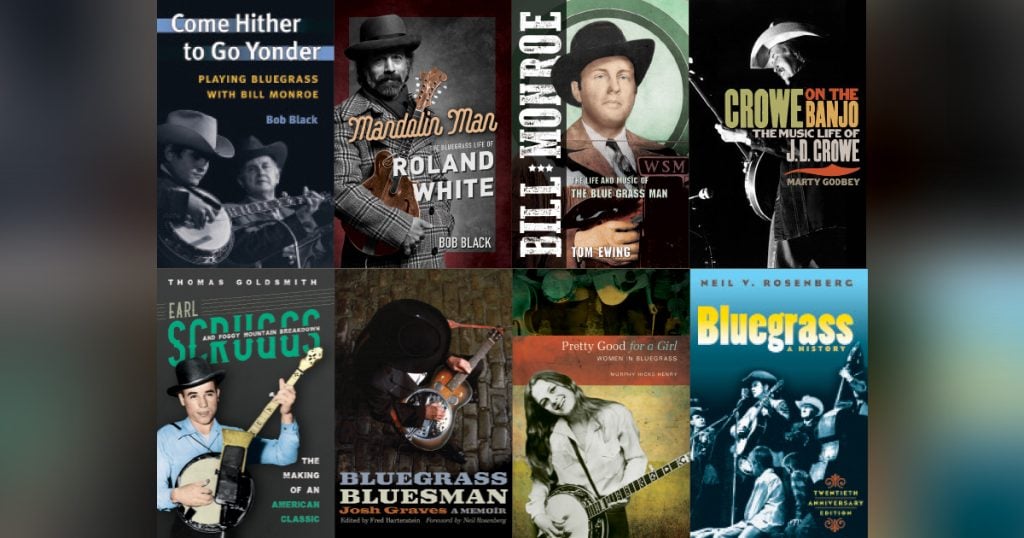

The University of Illinois Press has published many bluegrass titles in their “Music in American Life” series. These include (with the author’s name in parenthesis): Traveling the Highway Home (John Wright), The Stonemans (Ivan Tribe), The Bluegrass Reader (Thomas Goldsmith), Homegrown Music (Stephanie Ledgin), Bluegrass: A History (Neil Rosenberg), Come Hither To Go Yonder (Bob Black), Bluegrass Breakdown (Robert Cantwell), Gone to the Country (Ray Allen), Working Girl Blues (Hazel Dickens), Bluegrass Odyssey (Carl Fleischhauer and Neil Rosenberg), The Music of Bill Monroe (Neil Rosenberg and Charles Wolfe), Pressing On (Roni Stoneman), The Bill Monroe Reader (Tom Ewing), Pretty Good for a Girl (Murphy Hicks Henry), Bluegrass Bluesman (Josh Graves), Crowe on the Banjo (Marty Godbey), Foggy Mountain Troubadour (Penny Parsons), Bill Clifton (Bill Malone), The Music of the Stanley Brothers (Gary Reid), King of the Queen City (Jon Hartley Fox), Earl Scruggs and Foggy Mountain Breakdown (Thomas Goldsmith), Bluegrass Generation (Neil Rosenberg), Bill Monroe: The Life and Music of the Blue Grass Man (Tom Ewing), Don’t Give Your Heart to a Rambler (Barbara Martin Stephens), Industrial Strength Bluegrass (Fred Bartenstein), On The Bus with Bill Monroe (Mark Hembree), Mandolin Man (Bob Black), Bean Blossom (Thomas Adler). Quite an impressive list!

As a music fan, I enjoy learning about the history of the music that I listen to because it makes me feel closer to the music, the musicians, the culture and the tradition. When I started to learn how to play music, learning the history of who had come before me was also important. I came to realize that in order to have a strong musical foundation, I couldn’t just learn what Doc Watson was playing, I needed to learn what the players who inspired Doc had played. So, I dug into recordings by artists like Riley Puckett, Maybelle Carter, Jimmy Rodgers, the Delmore Brothers, George Shuffler, and Django Reinhardt. I listened to their recordings and I studied who they were, where they came from, and what inspired them. I think that the learning about the lineage of your favorite artists can be every bit as informative as the study of the artists themselves.

When I began writing this article, I wanted to validate my feelings about the study of music history, so I turned to an expert. Travis Stimeling holds a doctorate in musicology and is a professor of music history at West Virginia University. When I asked Travis why he thought the study of music history was important, he said, “I think it is important to study music history for lots of reasons. The big one for me is to recognize that, for the most part, musicians have always had the same sorts of economic, creative and technical pressures across time and across cultures. It is about how to make money and how to express yourself using the tools that you have at your disposal. When I teach music history, I make sure that my students can make the connection between the troubadours who were in France during the Middle Ages and contemporary song writers. They are both writing about universal human emotion and they are stuck with the vernacular language that they have. They also have to be innovative within fairly rigid song forms. How do you take the standard verse, chorus, verse, chorus type song and express something original? That, for me, is at the core of why you should study music history. You discover that for generations musicians have been grappling with the same problems and you can use those as models in your own creativity. The other thing is that it is important to know where you come from culturally and musically—especially in teaching bluegrass and country music—and connecting your own creativity to that place and honoring that tradition.”

For bluegrass enthusiasts and musicians, the books that are being put out by the University of Illinois Press’s “Music in American Life” series are extremely strong, reliable and vetted resources. The Press started the Music in American Life series in the early 1970s. At that time Dick Wentworth was the director of the Press and Judy McCulloh, who had a doctorate in folklore from Indiana University, was a staff editor. The current director and acquiring editor for music, Laurie Matheson, said, “Dick was interested in a series that would put music in the context of American social history, which was really his approach to the whole list and has shaped the identity of the Press since then. The idea was that you look at labor studies in the political, social, cultural context and you also look at sports, and film, and music in that context. So there was that rubric about how to approach a subject area and he put the idea of a music series in Judy’s hands to run with, which she did. Her initial consultant was Archie Green. He was a folklorist, a shipyard worker, and a longshoreman who was a very influential figure promoting the idea of working class culture as a worthwhile part of history…a worthy thing to document.

“Between that and Judy’s being steeped in folklore, which has that orientation of considering the experiences of ordinary people to be of value and worth documenting and celebrating, I think that really set the template for a music series that would be focused on music making at a grass roots level. The scope of the series Music in American Life is very broad. It spans from vernacular forms like bluegrass, country and blues to more ‘high-brow’ forms like classical music. In the thirty years that Judy developed that list she did work to bring that representation into the whole gamut. But, her heart was really in the music of the people. Why do they make it? How do they share it? How do they practice it? How does repertoire evolve over time? How do people interact with each other around the music? That is a quality of the series. I’ve been working on this series for almost twenty years now, and I certainly share that orientation.”

Judith McCulloh (1935–2014)

Neil Rosenberg was one of the first bluegrass authors who published through the University of Illinois Press. He was also a close friend of Judy McCulloh dating back to their days as students working on their doctorate degrees at the same time at Indiana University in the 1960s. Neil wrote the following as part of Judy’s obituary that was published by the Journal of American Folklore. “Judy was a key player in the move to recognize the importance of such music in American cultural history. Judy began working at the University of Illinois Press in 1968. There, she helped launch the Music in American Life series. An accomplished scholarly writer herself, Judy had a way of encouraging other scholars to follow and write about their ideas, and of suggesting to them things they hadn’t thought about before. It’s no wonder she had such a successful career as an editor. Under Judy’s direction, the University of Illinois Press’s Music in American Life series grew over a 35-year period to encompass 130 titles.” The series now exceeds 250 titles.

Laurie Matheson describes Neil Rosenberg as “a player in the early birthing of the bluegrass list. The connection that Neil and Judy had with each other led to the development of Neil’s Bluegrass: A History, setting that as the opening salvo, as it were, for the bluegrass list.” When speaking of the bluegrass projects on the list, Matheson continued to praise the foundational work that Judy McCulloh accomplished before retiring in 2005. She said, “Many of the projects that have been published since Judy’s retirement, and that are being published now, have their origins in Judy’s work.”

Neil Rosenberg, who had been put under contract to write his book about the history of bluegrass shortly after the series started in 1971, also pointed to Archie Green as an important part of the development of the series. He said, “Judy met Archie and they were like-minded. They shared an enthusiasm for music and cultural life. I would see Judy and Archie at American Folklore Society meetings and give Judy chapters of my book to read. She was my editor.” When asked if Judy consulted him about prospective bluegrass titles, Neil said, “She didn’t need advice from me. She was a regular at IBMA. She enjoyed the music and knew the performers. There wasn’t anyone she didn’t already know.”

Although Rosenberg was affiliated with the Press early on, his book wasn’t published until 1985 due to Neil’s other academic work. Neil holds Masters and Doctorate Degrees in Folklore and had been teaching Folklore at Memorial University of Newfoundland since 1968, however, most of the UIP authors are not academics. Laurie Matheson said, “Very few of the authors who have written books on our bluegrass list are academics. They don’t have dedicated institutional resources to support writing a book. Many of them are touring musicians, or they are agents, and their lives are elsewhere and they have to shoehorn in the writing of a book among those other activities. It is the network that Judy built that continues to give us the opportunity to work with these wonderful writers who tell their stories.”

Bob Black, who has had two books published through the University of Illinois Press said, “The University of Illinois Press, publisher of the series Music in American Life, has done more than anyone to promote interest in and knowledge of America’s rich musical heritage—including bluegrass. This was due in large part to the efforts of American folklorist and ethnomusicologist Judy McCulloh, a wonderful lady who helped navigate me through the writing process of my first book, Come Hither to Go Yonder: Playing Bluegrass with Bill Monroe. The music we love, bluegrass, has benefited enormously from University of Illinois Press’ in-depth historical studies of various artists and styles, elevating what was once a niche musical genre to an important and lasting element of America’s musical legacy.”

Regarding her work with UIP, Murphy Hicks Henry said, “I was fortunate to work with two insightful and supportive editors at the University of Illinois Press. The late Judy McCulloh came up with the initial idea for my book about women in bluegrass and, when she retired, Laurie Matheson came onboard. Both women were enthusiastic about my project and knowledgeable about my subject matter: feminism and bluegrass. Laurie, in particular, was always available to answer my numerous questions and was more than tolerant of the fact that I missed my deadline by several years. I’m delighted to be working with Laurie and the Press again on a biography of Maybelle Carter. (And I’m hoping, this time, to meet my deadline!)”

Publishing New Titles

When an author’s book concept is approved by the press, Matheson works closely with the authors to coach them through the process. After the book has been written, it is put through a process called peer review before being copy edited, designed, typeset, and published. Laurie said, “Even though many of the books are not scholarly, per se, they still have to meet standards of excellence of research and appropriate use of sources in addition to a style that is suited to the audience. The outside peer reviewers provide comments and often those comments will lead to revision. Then those projects are sent to our faculty board for final approval. Even though it is a list that is oriented towards non-academic readers, it still does include the credentialling of a scholarly press and the rigorous process of vetting the material to make sure that it is reliable and well executed. The real focus of the peer review is to make sure that the publication is making a real contribution to advancement of knowledge of the person, the scene, or genre and that it is written in a style that is appealing to the audience.”

As bluegrass fans and performers, we are extremely fortunate that the University of Illinois Press has been willing to pay such close attention to our slice of the music world. The publications that they have released have broadened our knowledge of the bluegrass genre. By informing us about our deep musical roots and our music’s connection to American life and culture—and telling the captivating stories of the pioneers who formed the music—these books give us a strong sense of where we came from and enrich our appreciation for who we are in the context of our music.