Home > Articles > The Artists > Mike Munford and the Soulful Machine

Mike Munford and the Soulful Machine

“I had no natural inclination towards music, beyond being drawn to the instrument through this one song that brought me in,”

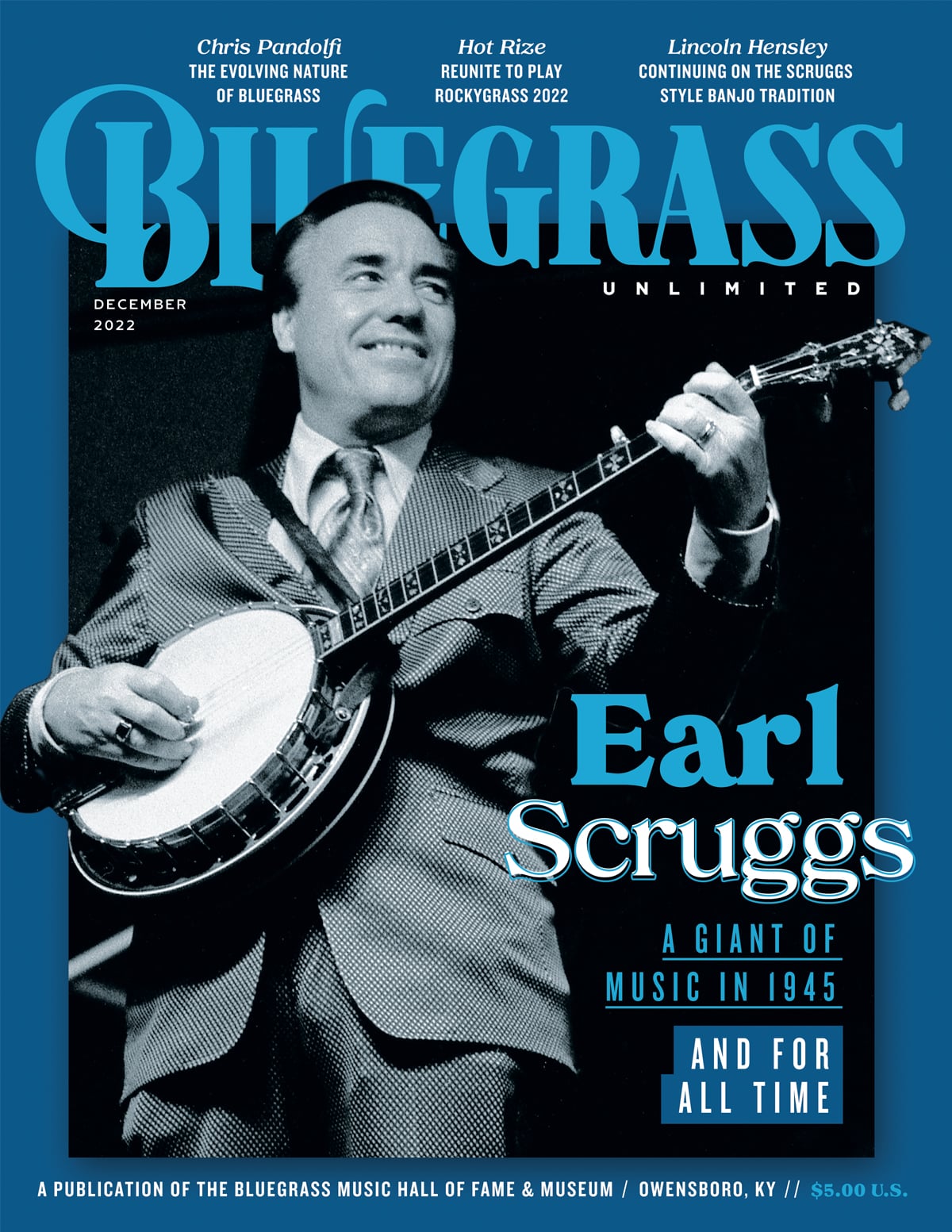

explains banjo picker Mike Munford, the 2013 IBMA “Banjo Player of the Year,” about his discovery of the instrument that would change his life. That one song was the Flatt & Scruggs’ classic, “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” which like the banjo has become a constant and important part of Munford’s life. Munford declares, “I tell you what always gets me. It’s that tune. No matter where I am playing, if someone asks for “Foggy Mountain,” I love it. Soon as I hear the title, I am just as excited, if not more so, than when I was 15. I have never tired of it. I have played it 1000s of times. Every time I hear I get just as pumped up.”

Like “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” the banjo has become an ingrained part of Munford’s identity, even more so as it is the way he has made a living his entire adult life. In conversation Munford speaks lovingly about the instrument, as one would speak of family or close personal friends. With a reverent tone he describes the power and wonder of the instrument and the unique way it can astonish and confound at the same time. He makes clear even after first discovering the banjo fifty years ago he is still in awe of the beauty of the sound it emanates. “What caught my attention about the banjo was the sound,” says Munford, “it was very exciting and very exotic. It was also the tone of it, the rhythmic aspect. It was not like a conventional instrument like piano or violin. Hearing the banjo and coming to understand how unusual this style of bluegrass banjo is, where the melody emerges out of these other notes that are all over the place, was a revelation. You just can’t believe what you are hearing. It still amazes me after all these years to hear all these other notes surrounding what seems like a hidden melody. The melody is within this cascade of filler notes, rolls, and rhythm patterns.” Munford was also equally fascinated by the “visual mechanical appearance” of the banjo when being played. He had long been intrigued by moving machinery and how things are made, and says, “the look of the right hand, where if you don’t know what’s going on almost doesn’t seem to make sense. The banjo has a great machine-like quality, but there is soul within it. This is a powerful combination. Real great bluegrass banjo is a soulful machine.”

Munford, who was born in 1958 in St. Louis and moved with his family to the Roland Park neighborhood of Baltimore shortly after he was born, says he was introduced to the banjo on September 9, 1973 as a 15-year-old by a friend who played him a pretty-rough version of the Flatt & Scruggs classic, “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.” “I remember thinking, I know what that is, I really like that, but I didn’t know what it was or know anything about the music,” recalls Munford. “I had come in from leftfield and knew nothing about bluegrass. My friend mentioned Earl Scruggs and said this is the guy who plays on the theme song for the Beverly Hillbillies. I remember really liking the fast banjo that came in when they introduced the Hillbillies.” Munford knew nothing about playing guitar or finger picking, but the mechanical nature of his friend’s right hand adorned with picks, steadily moving across the strings in an intricate choreography of dancing fingers fascinated him. Despite his friend’s limited skills, it was physically being in the presence of the banjo and seeing the physical motion creating the sound that had “notes flying in all over the place” that drew him right in. “It was definitely the sound of the instrument,” says Munford, “it was ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown.’ I had heard it on the radio and liked it but did not know what it was, and now seeing someone play it in front of me it grabbed me immediately. I said, ‘Can you show me how to do that?’”

As a curious minded, inquisitive teenager Munford thought he would dabble with the instrument until the next big thing came along. “That was 1973 and the next big thing never came along,” laughs Munford. “That was it.” From that moment Munford was devoted to learning all he could about the banjo. “It was like being hit over the head and being aware of something you really wanted to do,” he says.

For Munford it was also the excitement and adventurousness of bluegrass that captured his attention. He compared his first foray into listening to bluegrass to riding a roller coaster, “You start out going up really slow, and it’s just cranking along and then crests over the top of the hill and there is a huge impact as you shoot down the other side. It is that shift of going really slow to overdrive instantly. It was the transition from something that seemed relatively musically simple to something with all these melodies where I didn’t know what was going on. These sparkly sounds coming from all directions intrigued my interest in mechanics.

Things quickly fell into place for the budding banjo picker. Shortly after there was an article in the Baltimore Sun about bluegrass. At the end of the article it said if you want to read more, look up Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine. “What’s this,” thought Munford? “A monthly magazine about bluegrass. Great! It’s the old days, so I called information and got the number. Send it to me, I said. The magazine came in the mail and it was like a message in a bottle kind of thing on a desert island. A magazine all about bluegrass. It was the June of ‘74 issue and had the Seldom Scene on the cover. I read it cover to cover. There was an ad for the banjo newsletter in it. Good lord! A magazine about bluegrass and an ad for a banjo magazine. Sign me up. Now I’m getting both and all of a sudden it started falling into place.” The teenage Munford got his driver’s license soon after (in August) and was able to attend his first bluegrass festival in Gettysburg. “That’s where I get to see and hear this music up close and personal,” says Munford. “I sunk deeper and deeper into the music.”

For Munford some of the excitement and thrill of the banjo derives from how different it is from other instruments. He says when you learn guitar one of the first things you learn is a G chord and you can learn it quickly and as soon as you are already making music. “The mandolin and the fiddle are the same,” he adds. “Those first steps you take already sound musical. The first lesson on a banjo does not really fall that way. You learn rolls and patterns. These things played slowly make almost no sense to the ear. You don’t hear anything that seems to make sense. It’s not until you get it up to speed and tempo that you hear a sense of music. A rhythmic sensation starts to emerge. It makes it a unique instrument to learn.”

Munford’s dedication to learning the banjo was single-minded. He came home from school every day and played along with his record of “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.” When it finished, he would lift the needle back to the beginning and start over. He says, “I wasn’t even really interested in any other banjo tunes. It was that one tune, it got me right between the ears.”

After a couple of months of practice Munford was finally able to play a simple roll with a slide. “There is a basic slide and roll, alternating thumb roll, the square roll in ‘Cripple Creek,’” explains Munford, “and just being able to do that slide on the third string and this roll took a good bit of practice, but once that started taking shape, for me I was absolutely hooked. I was nowhere near being able to play ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’ or anything like that, but to play that roll over and over, not for a minute or two but for fifteen, twenty minutes, literally hundreds and hundreds of times, I was even more drawn in. I could only play two chords and this roll, but I thought it was great. Once I could feel it in my fingers and it sounded kind of right to the ears it was magical for me. It was like the clouds were parting and a ray of sunshine was pouring in.”

This incremental growth in learning and skill requires a dedication and commitment to master the tricky instrument. It reminded Munford of the animation flip books he had as a kid. When you flip through them at speed you see movement and motion, but if you look at one page at a time you do not get the same effect, it is simply a static picture until you get them moving at a certain speed. Munford equated those flip books to his developing skills on the banjo, “As you are learning the banjo you have to have faith that what you are doing will take shape, that this one roll will become something recognizable like the images in the flipbook.”

This commitment to the banjo was the start of a lifelong and still ongoing relationship with the instrument. It has been a relationship that, like a good marriage, has ups and downs, has highs and lows, and takes continuous effort to make it work, but is satisfying and fulfilling because of all of that. “Any endeavor it doesn’t matter what it is, requires dedication,” says Munford. Like any relationship there are bad times, struggles, and boredom. Munford with all his success still talks about not only his love for the instrument, but the daily hard work he has not only put in, but continues to put into his relationship with the banjo. “You constantly evolve and learn new things,” says Munford. “We all have moments of boredom, but you can counter that by listening to something new, taking a break and then coming back to it, or you can also snap yourself back into by listening to something you really have a handle on and see if there is something you have missed. I have done that with many things I thought I really knew and then realized I missed that little thing right there. So basically, there is no excuse for being bored, there are worlds of music to listen to, you can reexamine what you already know, and you can create something on your own. It’s an unbelievable thing to be involved with and such a gift that music gives you. It has the ability to hold your interest until your last day.”

The unconventional nature of the unwieldy five-string banjo has held his interest since first exposed to it as a fifteen-year-old. For Munford it is an all-occupying interest. In addition to his growing musical prowess, he also began to develop a reputation as one of the premier instrument repairmen in the country. Over the years many of bluegrass’ elites would call on Munford to help them when their instrument became damaged or fell in disrepair. Banjo-icon Tony Trischka had obtained an old pre-war flat-head banjo from Sonny Osborne. While it was always a great sounding instrument, something was not quite right with it. Trischka had tried several different repairmen and friends to see what else could be coaxed out of the old Gibson TB-3. It was not until Munford went to work on it the “true power and glory” of it was revealed. Through Trischka, Munford would find himself in comedian legend—and longtime banjo aficionado—Steve Martin’s living room in 2008 fixing the former Saturday Night Live standout’s banjo on his coffee table. The ever-humble Munford called it an incredible thrill to be able to help him out.

While focusing on some of the less glamorous aspects of the music industry—giving lessons, and becoming known as an elite repairman of instruments—allowed him to support himself financially through music (which is the unquestionable desire of every working musician), it also limited the amount he played outside of his hometown of Baltimore over the years. Munford never viewed his practical approach to making a living, which stunted the amount of national attention he received, as a negative. Instead, he felt fortunate to live in the Baltimore area where there was always steady work. He estimates he has played over 1500 shows in the Baltimore-Washington D.C region. Despite his lack of exposure, Munford was not completely unknown on the national radar. He was well-known throughout the country by other musicians and many big-time acts would ask him to sit-in when they were in the area or to join them for special shows at festivals across the country occasionally. Despite the odd foray into the big-time, Munford seemed content to stay close to home and make a steady, practical living through instrument repair, lessons, and his regular gigs around the area.

This lack of exposure and Munford’s quiet nature led to him becoming one of the more enigmatic figures in bluegrass. A strange thing then happened one day, Munford upped and joined a national touring band in the progressive outfit Frank Solivan and Dirty Kitchen in 2009. The move took everyone by surprise as they had become accustomed to the homebody version of Munford who never seemed to stray too far from the Baltimore area. Unsurprisingly, as soon as Munford started touring nationally with Frank Solivan and Dirty Kitchen the accolades began pouring in, culminating in 2013 when Munford received his first IMBA nomination and win for “Banjo Player of the Year” (he would also receive nominations in 2014, ‘16, and ‘19). Dirty Kitchen has also been similarly recognized since Munford joined, being nominated for “Instrumental Group of the Year” by the IBMA in 2014 and ‘16, and having their two most recent albums, 2015’s Cold Spell, and 2020’s If You Can’t Stand the Heat nominated for Grammy Awards.

Despite the accolades and growing recognition, for Munford it always comes back to the banjo and the sheer joy he derives from it, whether playing in front of a sold-out crowd or at home by himself. As with any good relationship, Munford’s connection with the banjo has evolved overtime. “Now when I play it or listen, I get even more excited because I am hearing it with fifty years of experience,” he says. “I hear details that I didn’t understand then. I hear things now that I didn’t understand twenty years ago. I appreciate aspects now I didn’t before, and I hear it differently. Sometimes I will just sit with a metronome and play rolls. I just love it. I am just as fascinated as I was when I first started because I can do more. I am not saying I have mastered it, but I have the ability to play those things with a precision and control that is very satisfying. It does not mean it’s the end of the road, there is always room for improvements.” Like any relationship where grand gestures and big events are great, it is sometimes the simple quiet one-on-one moments that are the most memorable and most important. For Munford he says the simple act of putting his picks on, tuning up and playing a few rolls, and hearing that tone emerge, “still gets me every time.” He continues, “As I get older, I realize time is of the essence and I want to enjoy this to my last breath. I really do, I want to do it forever. I can’t get enough of it.”