Home > Articles > The Archives > Lynn Morris: She Will Be The Light

Lynn Morris: She Will Be The Light

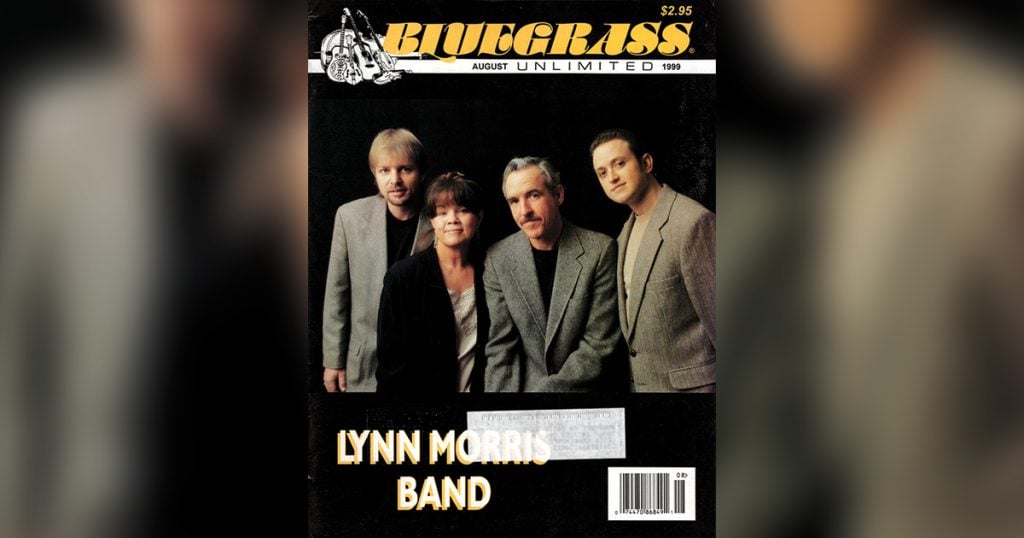

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1999, Volume 34, Number 2

Lynn Morris didn’t grow up in a “Blue Ridge Mountain Home” nor under the “Blue Moon Of Kentucky.” She grew up far from bluegrass country on the flat, dusty plains of West Texas. She was surrounded by cowboys instead of coal miners, by pedal steel guitars instead of banjos, and by endless baked ranches instead of small dark hollows.

Nor was that the only challenge she carried as she tried to make it in bluegrass. Strange as it may seem in this day of Alison Krauss, Missy Raines and Laurie Lewis, it wasn’t so long ago that women were second-class citizens in the bluegrass field. Especially if, like Morris, they started out as instrumentalists rather than as singers. Even more so if, like Morris, they presumed to become bandleaders.

So Morris was an outsider in two ways. And the obstacles placed in her path made her journey a longer one than it might have been—she didn’t record as a leader until she was 40.

In the long run, however, being an outsider helped her. It forced her to approach the music from a different angle from all the guys who grew up in Appalachia, and that altered perspective gave her a sound and sensibility that’s all her own. In a bluegrass field that suffers from too many good albums that sound too much alike, this singularity may be the most valuable asset of all. No wonder the IBMA has twice named her Female Vocalist Of The Year (in 1996 and ’98) and gave the Song Of The Year award to the title track of her 1996 album, “Mama’s Hand.”

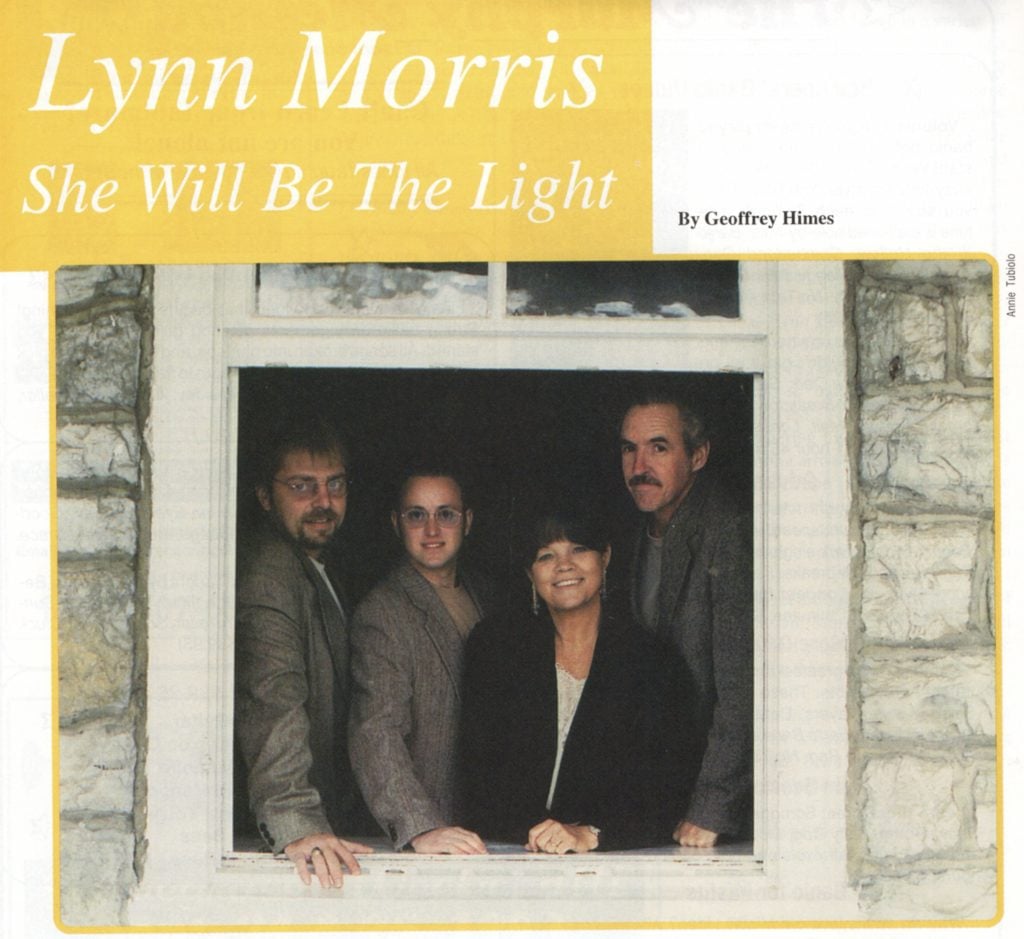

I’ll never forget the first time I heard her perform that song. It was under a canvas tent at the Festival of American Folklife on the Mall in Washington. Morris had her burnished brown hair pinned up in a bun, with the bangs hanging down to her eyes; she wore a white lace blouse, a blue-print cotton skirt and dangling blue earrings. Backed by three former members of the Johnson Mountain Boys (her husband Marshall Wilborn on bass, Tom Adams on banjo, and David McLaughlin on mandolin), she contributed the steady, insistent rhythm on acoustic guitar.

In writing “Mama’s Hand,” Hazel Dickens captured the push-and-pull of a mother-daughter relationship in a way no male songwriter could ever hope to. While Dickens’ own version is full of buzzing, soulful intensity, Morris’ flatter, gentler Texan voice gives the song a more melodic, more intimate feel. As she poured her heart into the microphone on the Folklife Festival’s temporary stage, Morris created the illusion that she was sharing a confidence over coffee at a late-night diner. And yet beneath that seductive understatement was a tensile strength, a determined insistence that she be heard and respected.

The same qualities can be heard throughout “You’ll Never Be The Sun” (Rounder), the new album from the Lynn Morris Band. Unlike most bluegrass albums these days, it contains neither compositions by Bill Monroe or the Stanley Brothers nor any transparent imitations. Instead it offers up another Dickens classic, three traditional-country gems, new songs from such contemporary songwriters as Jody Stecher, Bill Grant, James Leva, and Barry Tashian, a Nashville gospel hymn, a left-field jump-blues remake and a song from bluegrass’s roots in Irish music.

No matter what the song, though, Morris puts her distinctive stamp on the material. Her touring band (which finds Wilbom joined by mandolinist Jesse Brock and fiddler/banjoist Ron Stewart) recorded the album without guests and gives the music that traditional “driving” sound. And it’s the tension between those old-fashioned mountain arrangements and the modem warmth and intimacy of Morris’ voice that makes the album stand out.

“A friend once told me,” she says, “that the worst thing that can happen to a performer is for someone to hear you playing without being able to see you and to ask, ‘Who’s that?’ You don’t want that. I want people to hear this album and say, ‘I can’t hear this anywhere else but on a Lynn Morris record or at a Lynn Morris concert.’ We could do any number of Stanley Brothers or Flatt & Scruggs songs, but I don’t think we could bring our own stamp to them the same way we did to these songs.”

One thing that makes the album stand out are a number of songs that offer a specifically female perspective on life and love. Morris discovered Delores Keane’s version of “You’ll Never Be The Sun” on a compilation of female Irish singers during a trip to Ireland. The keening melody and maternal lyrics captivated Morris and by adding an Appalachian thump to the arrangement, she was able to turn the Irish ballad into a bluegrass song. Other songs, especially Dickens’ “Scraps From Your Table” and Crystal Gayle’s “Wrong Road Again,” also seemed to demand a woman’s viewpoint.

“Being a woman in bluegrass is important not so much because of the sound but because of the perspective,” Morris argues. “You bring different songs and a different approach to the music. There are a lot of songs I won’t do. I don’t want to sing a song about a man murdering his girlfriend. The longer I’m around, the more it means to me what message a song has. I won’t sing about women being victims; it’s not what I’m about and it’s not what 1 want to sing about.

“A successful singer who promotes her status as a victim isn’t being honest because you can’t be successful in this business if you’re a victim. And you see people in real life who get caught up in that and you can see how it holds their whole life back. I don’t want to be part of that. I don’t mind singing about relationships going wrong, because that’s part of life. I don’t think life is a bed of roses, and I don’t support that kind of song either. But when I hear some guy or some woman complaining about how the world has made them a victim, I just want to say, ‘Grow up. Get a life.’ It’s so boring to me.”

There’s nothing whiny about Dickens’ “Scraps From Your Table,” which is a defiant declaration of independence by someone who refuses to be the “other woman” any longer. When Morris sings, “I’m tired of cleaning up the mess she makes of you; scraps from your table. I’m sending back with you” the edge in her voice makes it clear that there’s little room for negotiation.

“A part of Hazel is so shy,” Morris divulges, “that until you really listen to her songs, you don’t realize how fearless she is. There’s this incredible honesty in her songs. It’s as if she’s saying, ‘Let’s skip the self-pity and cut to the chase—take a hike, buddy. I may be absolutely furious at you, but it’s not going to ruin my life. We’re going to make some changes here.’ ”

The female perspective is not the only one represented on “You’ll Never Be The Sun.” Morris’ husband, Marshall Wilbom, takes three lead vocals and shares a fourth when the couple recreates the Dolly Parton & Porter Wagoner duet on “If Teardrops Were Pennies.” Though the quartet bears Morris’ name, in many ways it’s a joint venture. And it’s no coincidence that three songs on the album were written by men who also share marriage and music with a partner-James Leva, Barry Tashian, and Jody Stecher (who perform with Carol Elizabeth Jones, Holly Tashian, and Kate Brislin).

“It’s really special when you can play music with your best friend,” Morris points out. “When you go out on the road, you’re not leaving anyone behind. It’s a real special connection and it comes through in the music. There’s a sense of honesty and of support. You’ve got someone right there that you can run a song by and maybe they can help you with a line or an arrangement. And who can be more honest with you than your spouse? We trust each other enough that we know we can be up front with each other.”

It’s no coincidence that “You’ll Never Be The Sun” includes three mainstream-country songs—by George Jones, Dolly & Porter, and Crystal Gayle—refitted for bluegrass. That’s the kind of music that Morris and Wilbom grew up on in Texas, and that lifelong affection for country music is one of the gifts they bring to bluegrass.

Morris was raised in Lamesa, Tex., the same Panhandle town that produced Don Walser. Morris never knew Walser, however, because she was a “nice Southern girl” and nice Southern girls didn’t hang out in honky-tonks. In fact, she kept her attempts to learn Johnny Cash and Merle Haggard songs on the guitar hidden away in her bedroom, safe from the teasing of her friends.

“West Texas was just a flat, brown country,” she recalls. “When I heard Dolly singing about hills and hollers and 10 kids living in a shack, I had no way to relate to it. But I responded to the honesty of it. So many forms of music have a contrived feeling to them, but this didn’t.”

It wasn’t until the 11th grade when her parents sent her off to a boarding school in Colorado Springs, Colo., that she began to share her enthusiasm for the guitar with others. There she met girls who played her songs by Bob Dylan, Tom Rush, Josh White, Jr., and Ian & Sylvia. And Morris’ enthusiasm for the acoustic guitar became a passion. She started studying classical guitar and playing folk music on the side. A few years later, at Colorado College, she discovered bluegrass.

“Some friends and I went to a bar one night, and there was a bluegrass band down from Denver playing live in a square room with pool tables and black walls. Charles Sawtelle played guitar. Mary Stribling played bass, Jerry Mills played mandolin, and Skip Barnes played banjo. They looked like they were having so much fun. They had an energy that folk music didn’t have. I just could not leave it alone. I knew at that point I was going to do anything and everything I could to learn that music.

“Most of all, I fell in love with the banjo. My sister Kay had a banjo she had never played, so I took it to school. I had studied classical guitar for several years and had gotten fairly fluent in both my hands, so picking up the banjo wasn’t that hard. But practicing classical guitar was a grind; you stayed in your room by yourself for four hours a day. It was nothing like bluegrass banjo, where you go and play in bars for people who are screaming. So bluegrass became my social life.”

When Morris graduated from college in 1972, Mary Stribling made her an offer she couldn’t refuse, “Why don’t you move to Denver and we’ll start a bluegrass band?” Morris got an $80-a-month apartment, a temp job, and devoted herself to the City Limits Bluegrass Band that she and Stribling co-founded with Pat Rossiter. Thanks to Morris’ picking and Stribling’s hilarious stage banter, the trio soon became popular throughout the Rocky Mountain region, especially at ski resorts. The group lasted six years and released two albums.

Denver was an unlikely but exciting center for bluegrass in those days. Charles Sawtelle, Stribling’s old bandmate, had formed a new group with Tim O’ Brien, Pete Wernick and Nick Forster. Calling themselves Hot Rize, they put Colorado on the bluegrass map. At the same time, the Denver Folklore Center (now known as Swallow Hill) was a music store, music school, and concert venue where every local and visiting acoustic musician seemed to end up. And Morris spent nearly every hour when she wasn’t working or sleeping at the center.

The encouragement she got there gave her the confidence to start entering banjo contests. She won a lot of them, including the national championship at Winfield, Kans., in 1974 and ’81. It was at these contests that she got her first inkling of the gender barriers in bluegrass.

“In Winfield,” she explains, “the judges were secluded; they only knew your number. You weren’t supposed to say anything; in fact, if you did, you were disqualified. The judges didn’t know your sex. race, or even your name. All they heard were the two or three songs you played. I won the first time I entered that contest. But I have played in contests where the judges watched the contestants, and was shocked to hear later that I hadn’t won because I’m female. I think all that stuff just made me more determined to figure out some way to get something happening in the bluegrass music business.”

Morris had a good life in Denver, but after six years in City Limits and two years in the country band Little Smoke (which also briefly boasted Junior Brown as a member), she decided it was time to get serious about bluegrass. And to do that, she had to travel East.

“I felt like I had hit the wall in Colorado,” she explains. “I knew everyone who played the music and almost everyone who listened to it. I decided I had to get back East where it was going on so hot and heavy. We knew the Stanley Brothers came from this romantic, storybook place in Virginia, but none of us had ever been there. It was time to go see it for myself.”

Her Hot Rize pal Pete Wernick got her an audition with a modestly successful Pennsylvania band called Whetstone Run. While she was waiting for them to make a decision, she visited her sister in San Antonio, and attended a bluegrass jam session at Snaveley’s on 6th Street in Austin, Tex. Morris started singing and suddenly heard this strong, dead-on harmony vocal coming from the direction of the bass player. She turned around and there was Marshall Wilborn.

“It was just perfect,” she remembers. “He had just ended a relationship and so had I. He was nice; he was a good musician; we liked the same kind of music. He took me over to his folks’ house and they had the same kitchen linoleum as my parents’ house, the same carpeting, the same TV, the same Siamese cats. I had never experienced anything quite like it.

“Marshall had just written a song for Doyle Lawson called ‘Mountain Girl,’ and as soon as Doyle sent a tape of the recording, Marshall played it in his pickup truck for his buddies and me. I thought, “My gosh, a guy who writes songs like this must have a heart the size of Texas. And he likes me. And I like him right back.’

“A few days later I got the good-news call from Whetstone. I put my banjo and suitcase in my Volkswagen Rabbit and left for Pennsylvania. I remember telling Marshall, ‘Come see me,’ like you do to people all the time. I had no idea he would actually do it. But he’s a very literal person. A few months later, he called to say, ‘I’m coming to see you.’ ”

During the week Wilborn spent with Morris in State College, Pa., he got to know her bandmates in Whetstone Run as well. As fate would have it, the band’s bassist gave notice during the visit, and the band offered Wilborn the job. He ended up playing with Morris in Whetstone Run for three-and-a-half years. The band played some festivals and a lot of clubs, mixing bluegrass standards with a sprinkling of originals.

In 1986, though, things began to unravel. Bandleader-mandolinist Lee Olsen got a job offer from the Keith Case Booking Agency in Nashville; singer-guitarist Chris Jones took ill and temporarily had to come off the road, and Wilborn got an offer to play bass for one of the giants of bluegrass, Jimmy Martin.

Whetstone Run disbanded and after a few months with Martin, Wilborn got an even more attractive offer—the bass gig with the Johnson Mountain Boys. One of his new bandmates, David McLaughlin, recommended Winchester, Va., as a place to live and that’s where Morris and Wilborn have been ever since.

Those years of 1986-88 were tough ones for Morris. Except for one tour with Laurie Lewis, she mostly stayed home in Winchester while Wilborn was out with the Johnson Mountain Boys.

“I was driving a limousine and not playing much,” she recalls. “It was hard for me. The Johnson Mountain Boys would be playing in the area, and people would come up to me and say, ‘Why aren’t you up there?’ I couldn’t even begin to explain. I’d never been the one left at home while the man is out gigging every weekend with the band of his dreams. I was so happy for Marshall, and I was crazy about the band, but it was awful. I was just about at the end of what I could take as to not playing anymore. And it was just at that point that the Johnson Mountain Boys decided to break up.”

Wilborn and his fellow ex-Johnson Mountain Boy, banjoist Tom Adams, decided to put a new band together with Morris. When they cast about for a name, Adams said, “Why don’t we just give the band your name?” Lynn added the word ‘Band’ because “it was most definitely a collaborative venture musically!” It meant several big changes for her, because for the first time she’d be a bandleader and for the first time she’d be a lead singer and rhythm guitarist rather than the banjo player.

“I had always thought of myself as a banjo player,” she insists, “and I had only sung when there was no one else to do it. But more and more, I was getting attention for my singing. But I don’t think I really got very good as a singer until I started this band and switched from banjo to guitar. To be a good singer, you have to give it your total concentration; you can’t be thinking about anything else. To drive a song really well on banjo and never let up also requires your total concentration.

“If you’re singing, your banjo playing is going to suffer. And vice versa. Having done it for years with this band, I know I sing better when I’m playing with rhythm guitar than when I’m playing banjo. Rhythm guitar is also incredibly demanding, but if you’ve done your homework and kept your chops up, you can sing and do it. In fact, guitar works best when the person singing is playing it. The best example is Del McCoury. When he’s singing he plays lighter, and when he stops singing he really punches it at just the perfect moment.”

When asked about the special challenges of being a female boss in a male- dominated world, Morris replies, “In a band context I don’t think it’s at all constructive to focus on the gender issue. But it is critically important to realize that men/women relationships can create a lot of emotional baggage that we all tend to carry around—stuff that can make working together difficult to say the least. It’s just one more thing to have to deal with in a situation that’s already loaded with complications. Some men simply prefer not to work with women, so you just have to find musicians who can. But if the music thing is happening, and there’s mutual respect, things can really work out beautifully. I found I had to work on my musicianship, because if you’re going to work with great musicians who have played with the Johnson Mountain Boys and Jimmy Martin, they know their stuff and expect you to know it, too. I wasn’t as good as I thought I was. It was one of the most humbling experiences I’ve ever been through.

“The big surprise was I was expected to know everything all the time. I was expected to make everything work all the time. And everyone was going to be watching me 24 hours a day to see if that happened. Well, I’ve never been any kind of quitter, so the only thing I could do was dig in and do it.” She did it well enough that Rounder Records signed the group and released the debut album, “The Lynn Morris Band,” in 1990. Morris, Wilborn, and Adams still hadn’t found a permanent mandolinist yet, so they used Ronnie McCoury on the session. It introduced the now-familiar formula of a Hazel Dickens composition, a handful of mainstream-country chestnuts, and songs from contemporary, progressive bluegrass writers. Within a few months, the album had placed five different songs within the top 22 on the Bluegrass Unlimited national radio survey.

That paved the way for the even greater success of 1992’s “The Bramble & The Rose,” which featured David McLaughlin on mandolin. Barbara Keith’s title track was a folk song inspired by “Barbara Allen,” but the balance of the album was devoted to country oldies by Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, and Tom T. Hall, and bluegrass numbers from Jim Eanes and the band members. The album topped the Bluegrass Unlimited album chart and spent nine months in the top 10.

The final breakthrough for Morris and her group came in 1995 with the album, “Mama’s Hand.” With McLaughlin again holding down the mandolin chair, the group achieved a cohesiveness that made it one of the top bluegrass bands in the business. The highlight, though, was the title track, a Dickens’ composition which also topped the Bluegrass Unlimited radio survey and won the IBMA Award for Song Of The Year.

“I lost my mother in ’84,” Morris reveals, “and I had been back and forth to Texas to help take care of things. One day I was at home in Winchester while Marshall was on the road, and I heard Hazel do ‘Mama’s Hand’ on WAMU. It hit me like a ton of bricks. I said, ‘Wow, that’s an incredible song.’ I realized that saying goodbye is not just leaving home at 16; it’s when you drive out of Texas for the last time after burying your mom. I got a tape of the song and tried to learn it because it meant so much. I couldn’t even get through it because it was so emotional. Finally I learned it and we started doing it.”

After the success of “Mama’s Hand,” Morris suffered a setback when both Adams and touring mandolin player, Audie Blaylock left to pursue other opportunities. She and Wilborn had to rebuild the band from the ground up. They found two young pickers who had been picking with Midwestern family bands by the time they were eight.

Indiana’s Ron Stewart, who plays both fiddle and banjo, was playing mandolin with Petticoat Junction. That band stayed with Morris and Wilborn on a stopover in Winchester. The couple liked their visitor so much that they asked him to fill in on some of their dates in 1997. The combination worked so well that Stewart was offered a full time job with the band, and will soon be starting a solo recording project of his own on the Rounder label.

Kentucky’s Jesse Brock, who plays mandolin, had done an earlier stint with the Lynn Morris Band in 1992, but he rejoined the group for good last year. He toured for years with the C.W. Brock Band and then with Chris Jones & the Nightdrivers.

This new lineup proved so satisfying on the road that Morris decided to take a chance and make her fourth album without any guests (except for McLaughlin’s lead guitar on Stewart’s rip-snorting instrumental, “Twister”). The quartet was more than up to the challenge, and “You’ll Never Be The Sun” should cement the reputation of the Lynn Morris Band as one of the major fixtures in the bluegrass firmament.

“I really prefer not to be thought of as a ‘woman’ bandleader, but just as a bandleader. That’s all. I don’t think being a band leader is a piece of cake for a man either. You’re basically taking on the task of making the impossible possible, and the inconvenient worthwhile. You’ve got all the non-music related headaches of running a small business, and it’s a serious challenge to find time for the music! I don’t get a lot of sleep.

I’ve had women tell me that they really appreciate having someone onstage they can personally relate to, and I do see more women actively listening to, playing, and doing a good job of promoting bluegrass these days. That’s a very positive change! Bluegrass music needs all the passion and enthusiasm and support it can get—women have a lot to give, and there’s room for everyone.”

Geoffrey Himes has contributed to both THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF COUNTRY MUSIC and THE ROLLING STONE JAZZ AND BLUES ALBUM GUIDE. He writes regularly for the WASHINGTON POST. BALTIMORE CITY PAPER. REQUEST. NO DEPRESSION and COUNTRY MUSIC MAGAZINE.