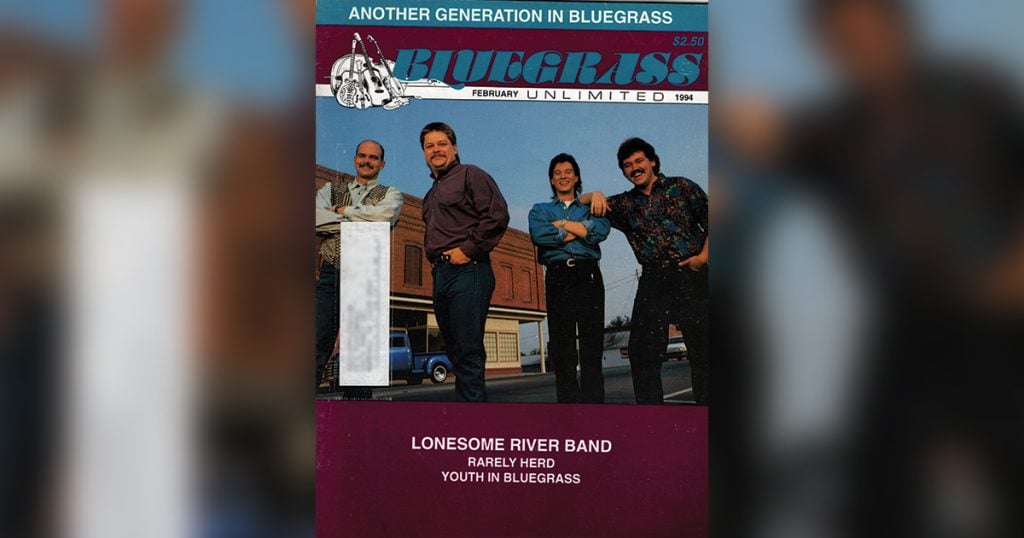

Home > Articles > The Archives > Lonesome River Band—It’s About Excitement!

Lonesome River Band—It’s About Excitement!

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1994, Volume 28, Number 8

A wealth of bluegrass history has been made in the counties along the central North Carolina/Virginia border. This area was a mainstay on the circuit for Reno & Smiley, Flatt & Scruggs, and other first generation bands. It became the home of promoter Carlton Haney’s legendary Camp Springs festivals, and has spawned an abundance of bluegrass talent including banjo greats Allen Shelton and Alan O’Bryant and singer Jim Eanes.

Tim Austin had no idea of the rich bluegrass heritage developing around him as he grew up in the 1960s in Ruffin, N.C., halfway between Reidsville,N.C., and Danville, Va. In fact, though he got his first guitar at age seven or eight, he was a teenager before he discovered bluegrass music. Prior to that, Tim’s main source of musical inspiration was his father’s record collection.

“My Dad liked early jazz music,” he recalls. “He liked Charlie Parker, Dave Brubeck, even big band stuff, like Benny Goodman. I listened to a lot of that. That was probably the first music that I really liked and was influenced by, because that’s about all the records he had.”

Tim’s introduction to bluegrass came when a family of musicians moved in across the road. He began to hear them practicing, became captivated, and ultimately went over and introduced himself. Tim immediately struck up a friendship with the Moore Family. He soon was invited to join their band as the banjo player and he became obsessed with learning to play banjo. At 14, he had received his first taste of the music business and he realized that he wanted this to become a career.

Tim became interested in radio soon afterwards, and at age 16 he began working as a disc jockey at various stations in the area. “I worked in radio all through high school, and two years after high school, and then on and off until I started the [Lonesome River] band,” he says. Working in radio, Tim developed a keen ear and a broad range of musical knowledge. “The main format was adult contemporary music, but at night some stations would change the format. I worked all the shifts, so late at night I had a chance to play heavy metal, then in the mornings I signed on for a while—all that was pop-oriented.”

While in high school Tim also began listening to bluegrass records, and he counts Flatt & Scruggs, Del McCoury, and Boone Creek among his biggest influences. He had little early exposure to the music in a live context, but he still remembers one of the first shows he attended. “I went to a high school and saw Ralph Stanley one time. Keith Whitley was with him. It was great! It was killer! I’ll never forget that as long as I live.”

After several years as a banjo player, Tim rediscovered guitar and found it to be his first love. Upon graduating from high school, he joined the Lynchburg, Va.-based Lower Forty Grass. With this band, he got his first experience of extended touring—they were on the road for a month on the first road trip. Tim worked with Lower Forty…for about a year, but he was beginning to formulate his own ideas about a new band sound.

In 1982 Tim formed the Lonesome River Band. The original members were “the cream of the crop” of area musicians, Steve Thomas on fiddle and mandolin, banjo player Rick Williams, and singer/bassist Jerry McMillan. Asked where the band name came from, he explains, “There was a song— it wasn’t the ‘Lonesome River’ song that the Stanleys did—there’s another ‘Lonesome River’ song. Wes Golding, who played guitar with Boone Creek, was with another group called the Shenandoah Cutups. I think they did that song, and we just sort of named the band after that, and we’ve stuck with it.”

Tim has stuck with the Lonesome River Band for more than ten years now, though many of those years were difficult enough to have caused a less tenacious individual to go back to his day job. In a way, Tim does have a day job. In 1987 he began building his own recording studio in an outbuilding near his house in Ferrum, Va. His initial motivation was to gain more creative control for the band in the recording process. He would run the studio, engineer and mix the recording, and thus would be able to produce exactly the sound the band wanted. Yet Tim’s irrepressible resolve took him far beyond producing quality recordings for the Lonesome River Band. In addition to engineering the LRB’s “Looking For Yourself” (Rebel 1680) and “Carrying The Tradition” (Rebel 1690), Tim has recorded such bluegrass artists as Tony Rice, Del McCoury, and the Bluegrass Cardinals at his Doobie Shea Studios. He works with country, gospel, and rock groups as well, and enjoys inspiring musicians to produce the best performance possible as much as he enjoys punching buttons on a console.

Ironically, as Tim was beginning construction on the studio where he would produce the band’s recordings, the Lonesome River Band was precariously close to disbanding. The rigors of road travelling, business management, personality and creative conflicts, personnel changes, and meager income took their toll on the LRB early on, just as they have on many other young bands, now long forgotten. But just when the Lonesome River Band was at its lowest ebb, in the late ’80s, something happened that dramatically changed the band’s fate.

That something was a hot young mandolin player and singer from Vermont, named Dan Tyminski. Tim recalls, “I remember when Danny came to the band, Jerry McMillan and I were about to quit because it was really bad at that time. The work wasn’t as good; it was hard to make a living.

Dan drove to Pennsylvania [to meet us]—we were working a date there. When I heard him sing, I couldn’t believe it. I just had to hear one line and I knew. It was exactly what we needed. It was funny because we had just played a show less than two or three weeks before with Dan’s band, Green Mountain Bluegrass, and sometimes you’re right up on something and don’t know it.”

Indeed, one of the most striking things about Dan is his incredible natural singing ability. “I’ve been singing since before I can remember,” he says. “My parents have tapes of me singing long, complicated songs that I have no recollection of. I never remember hearing them or learning them. My grandparents used to call me up on the phone and make me sing. I was their little star.”

Though Dan hails from Vermont, his early musical experiences sound more like those of a boy growing up in the hills of Virginia. “My parents used to always listen to old-time country music—Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams—a lot of stuff like that. On weekends my parents would take me to every bluegrass festival that we could go to, and to shows where my mother [would] go up and sing a little bit. My mother used to play guitar a little and sing in Vermont and upstate New York, and she’s the first one who I noticed that made me want to do it. When I was about six I learned a couple of chords on the guitar.

“My brother, Stan, was stationed in the Navy in Norfolk, Va., and he got to liking bluegrass music from someone he met there. When he came back to Vermont on leave, he had a mandolin with him, and he left it with me. That’s what got me into bluegrass—that was when I was probably about eight. I performed with my brother a few times when I was nine or ten. We played just guitar and mandolin at a few local things. I played mandolin from when I was eight until I was thirteen, when I decided I wanted to play the banjo.”

He describes how that transition came about. “When I was 12 1/2 my brother came home and he had a copy of ‘J.D. Crowe & the New South’— the record with Douglas, Skaggs and Rice. It absolutely killed me. And what killed me about it was Crowe’s banjo playing. The timing and tone he had were so good, it amazed me that that could move me so much. I heard it in my driveway, when my brother first drove in. He was playing it on the car stereo and I heard it, and rather than go to him and say, ‘Oh, I’m so glad to see you,’ I was glued to that tape from then on. After that I had to have a banjo, I had to play the banjo after that. That hit me harder than any music has hit me since.

“The first time I got on stage on the banjo, I’d been playing about two months, with a fellow by the name of Smokey Greene, who made me take every break to every song, and I could not play. He said, ‘Oh, you’ll learn quicker that way.’ I said, ‘I don’t want to learn that quick!’ Smokey Greene was the one who got me on stage and really started making me play. I was really shy. I was very content to be in a room playing by myself. When I got home from school, I didn’t really care about going out to play baseball, I used to go to my bedroom and play music.”

Though he lived in the north, Dan was lucky to be able to see many of the bluegrass masters, including Larry Sparks, Doyle Lawson, Jimmy Martin, and the Country Gentlemen, during his formative years. He initially was drawn to the sounds of the newer, more modern bands. “When I really started liking bluegrass, I liked the more progressive—the Bela Fleck and the New Grass [Revival]—groups like that. My brother always played tapes of Ralph Stanley, Jimmy Martin, Del McCoury, and Larry Sparks. At the time that I first started listening, if it wasn’t that J.D. Crowe album, or something really progressive, I wasn’t into it. It used to annoy me that that’s all he would play, the really old standard groups. Now I really treasure the fact that I got to hear that so much. I can’t count the road hours that we spent listening to traditional bluegrass, and I see that coming out in me more now. That’s really what I like more, it took me a while to discover that what I liked was…it all fell back to the roots of it. I think Del McCoury probably more than anyone—that was the changing point for me. Once I got to where I really loved Del, I found out I just loved it all.”

It is clear that those traditional influences have left an indelible mark in Dan’s singing. Though he speaks with a mildly northern accent, he sings with an amazing, natural, southern sounding “authenticity.” He explains, “I think that is part of the chameleon in me. It’s what I liked. When I heard people like Ricky Skaggs sing, or Tony Rice, Jimmy Martin, or Larry Sparks, it’s just what I was taken to. If I really like something, I really get infatuated with it. I think the southern vocal style is something that I always liked to listen to, and it just kind of happened. I didn’t realize I was doing it until people started coming back to me and saying, Where are you from?’

“I don’t try to copy any style, I just try to sing what sounds good to me. There was a point when I would try to say words certain ways, and I can’t feel the song if I do that. I can’t think about it, I just try to keep the story in my head—what is the song about—make it sound believable, that’s the best for me.”

Dan first heard the Lonesome River Band in the summer of 1988. “Our band had a chance to play with the Lonesome River Band in upstate New York, and I got to hear them. The rhythm section excited me. They were very powerful…My brother always tried to drill it into my head that the good timing and the rhythm had to be there, but I didn’t know what he was talking about at the time. I met the Lonesome River Band at the Winterhawk Bluegrass Festival through Kevin Church, who was playing with the Country Gentlemen at that time. I told him that I was looking for a band to join. He knew I was a banjo player and he knew that the Lonesome River Band was looking for a banjo player, and he was kind of my contact.

“I called Tim and we met somewhere in Pennsylvania. We picked a little while, and it clicked. It felt good. I’d never been driven that hard by the rhythm around me. That was one of Tim Austin’s main things—make it solid, work off the rhythm, then whatever you do you can always fall back on the good, solid rhythm. I think that’s one of the things I liked most about the band. The other thing was that they were a Southern, working band. I knew that I wanted to play bluegrass music, preferably in the South. I thought that was a good opportunity to get in the heart of bluegrass country.

“My goal was to join as the banjo player, and I was the banjo player for a little while, but as it happened there were two musicians that we needed—a banjo and a mandolin—at that time. It was more comfortable to play the mandolin and sing, since I was taking on a little more of a singing role than I had been. At the time I joined the Lonesome River Band I didn’t have the vision that I do now. I just wanted to play bluegrass—everything else kind of fell into place a couple of years down the road.”

Dan’s exciting, bluesy, mandolin playing, dynamic energy, and incredible vocal talents were indeed what started to turn things around for the Lonesome River Band. His first recording with the group “Looking For Yourself,” made the bluegrass world sit up and take notice. It sold better than any previous LRB release, received significant radio airplay, and brought the band’s vocal talents into the spotlight. Soon the work began to pick up.

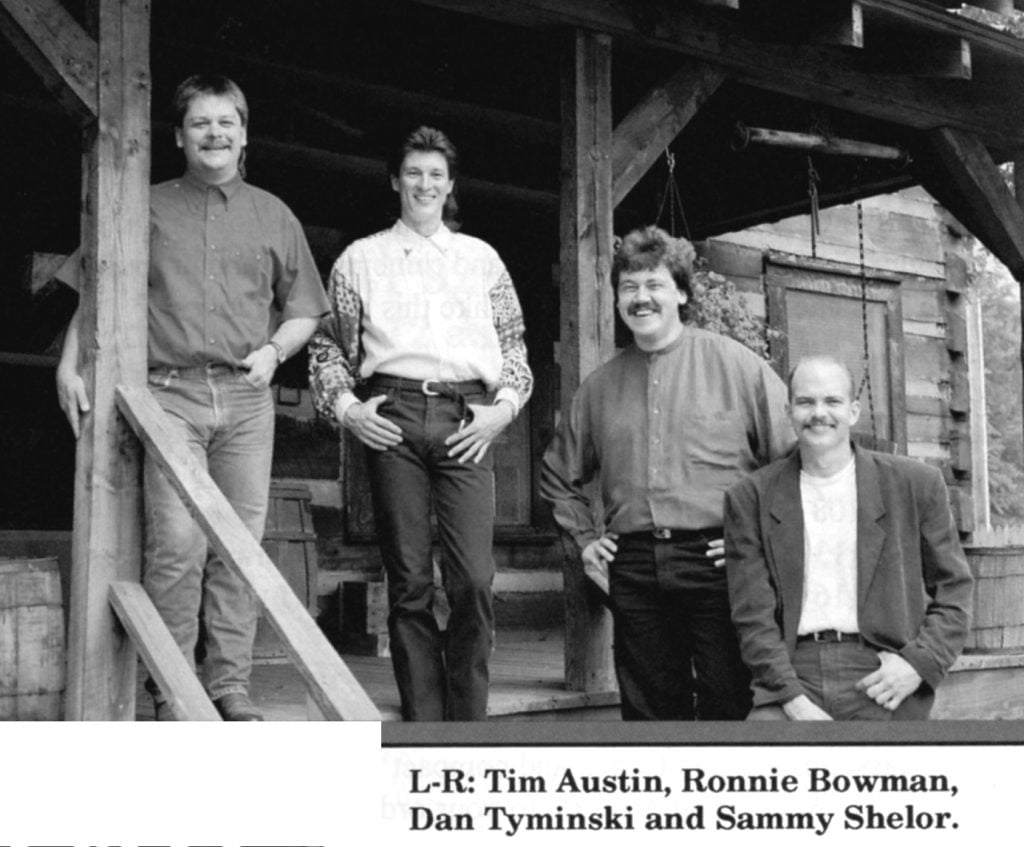

But the crowning event in the Lonesome River Band’s metamorphosis was yet to come. In the fall of 1990 Tim recruited a North Carolinian named Ronnie Bowman and a Virginian named Sammy Shelor, not realizing until a few months later that he had finally hit upon the right ingredients to make his magic formula work. “Sam and Ronnie joined within a week or two of each other,” recalls Tim. ‘I’d been trying to get Sam for a long time. We went through two or three people, and we always called Sam, to see if it was time for him to come. He hung in with the Virginia Squires, and I respect him for that.”

Sammy Shelor was born with bluegrass in his blood. His family lived in Meadows of Dan, Va., right on the Blue Ridge Parkway, a hot bed of traditional music. “My grandfather and his father were old-time musicians,” he states. “My grandfather grew up in the early ’teens, ’twenties. Charlie Poole used to come through our area a lot, and they were drinking buddies. They played together, played dances. My grandfather was exposed to that, and he played for years and then quit. When I was about five years old, he bought another banjo, and that’s when I got interested in learning how to play. He made me a little banjo out of a pressure cooker, out of the ring. He used that as the outside of the rim and made a wooden rim to go inside of that. It had tractor bolts and clothes hanger wire to hold the head on, a tin head, and a neck that we whittled out to scale. So that’s what I learned to play the first couple of tunes on.

“My other grandfather, Sandy Shelor, bought me a full-sized banjo when I learned how to play. He told me he’d buy me one, so as soon as I learned how to play, I ran over to his house one night and showed him, and I came back with a banjo!”

Sammy recalls, “I saw Flatt & Scruggs when I was about five years old—it was one of the last tours they did together. I really can’t remember a lot about it, but I can still picture them on stage. That was one thing that inspired me to learn to play, was seeing Earl play, and just that overall sound. Still now, that’s one of my favorite bluegrass bands. They had a classic sound all their own. Then I started going to fiddler’s conventions, and the local gatherings where everybody played music, and I’d jump on stage at the first chance I could get. I used to play at Mabry Mill, on the Blue Ridge Parkway, every Sunday for years and years.

“When I was about ten years old I got in a band with a guy named Leon Pollard. He was a big album collector, and he used to make me 8-track tapes to listen to. I didn’t have the money to buy a lot of records, but he started exposing me to a lot of different music—The Seldom Scene was getting started during that time, and J.D. Crowe & the New South, and then I discovered Boone Creek and I was in love! As a teenager, I would come home from school every day, and sit in front of the stereo learning ‘One Way Track’ note for note. I know the whole album inside out. That’s where I learned timing and that sort of thing.”

Soon Sammy got his first professional job with a band. “I moved to Richmond in 1981 and went to work with a group called the Heights Of Grass. I worked with them in ’81 and ’82. The Virginia Squires evolved from that band. We started the Squires in 1983 and disbanded in ’89.”

In the mid-’80s, Sammy began to experiment with electric guitar, while honing his baritone harmony singing. “I bought a Telecaster and started playing country guitar, mainly [to avoid] starvation in the wintertime. When I was living in Richmond, I needed to work, and I found out there was a shortage of harmony singers, so I learned to play guitar and kept working in the wintertime. That’s where I learned a lot about singing and playing country. I listened to jazz. I got into [David] Grisman real heavy and started playing mandolin some. I listened to a lot of acoustic jazz stuff. I really didn’t get exposed to true jazz until about ’86 or ’87. I started listening to the old Benny Goodman stuff and Charlie Christian, and started taking lessons from a jazz guitar player, who turned me on to that kind of stuff.

“After the Squires disbanded,” Sammy continues, “I decided to move back to the mountains where I was happy, and would find work where I could. I was working at a grocery store owned by my girlfriend, and John Bowman, who is with Alison Krauss now, came in the store one day and said the Lonesome River Band was looking for a banjo player. I didn’t think much about it; I hadn’t heard those guys in four or five years. Then I remembered Norman Wright telling me about this tenor singer that these guys had that was just out of this world, and I just got to thinking, ‘Well, they’re close by and it’s a bluegrass band, and it might be something worth checking into.’

“The next morning I called Tim and he brought me the tapes up that afternoon. I put ‘Looking For Yourself in the tape player and when I heard Dan sing, I said, ‘This is it! I’ve got to get involved.’ And then I heard Ronnie Bowman was going to be involved. I knew him from the Lost and Found, but I’d never met Dan before. When I heard that voice, and then I got to thinking about Ronnie’s singing, I said, ‘That’s going to be the blend of the century, right there.’ So I went down and we got together and played some, and when I left they said I had the job.”

Ronnie Bowman’s involvement in the Lonesome River Band seems to have stemmed largely from a fortuitous twist of fate, from being in the right place at the right time. “We needed somebody to sing with Dan,” Tim states. “I started thinking about it, and I had seen Ronnie just a couple of weeks before that at a party. It was right after he quit the Lost & Found. I heard him sing at the party and couldn’t believe he wasn’t with a band. I immediately called him and he immediately took the job.” Like Dan, Ronnie has been singing almost as long as he has been walking. He recalls, “I started singing in church when I was three years old. I come from a large family; there were five kids—four girls and I was the only boy. We all sang and that’s how I started playing music, basically going around, singing in church, with my sisters and my mom and dad. I had two sisters who played the piano and my mom played the guitar. My dad played the guitar and the banjo. One of my sisters played bass. It was like a family thing—we all went to church and played music. Local churches around North Carolina and Virginia. I enjoyed that. That brings back a lot of good memories for me. We used to invite folks over to the house. Sometimes we’d invite other people that picked and sang, too. They’d come over and they’d have kids and we’d all be jamming and then we’d eat and all the kids would run around outside in the yard.”

But like Tim, Ronnie didn’t discover bluegrass until his high school years. “The way that I got turned on to bluegrass music was through my wife’s sister’s boyfriend,” he confides. “He played bluegrass and I sang and played music too. I saw him pick up the guitar and burn a good guitar break and then he picked up the mandolin, and I was amazed with somebody being able to play fast and make it sound as good as he did. I heard a tape of Ricky Skaggs and Tony Rice, it was just guitar and mandolin, and I fell in love with that. He also let me hear a tape of Boone Creek, and that totally blew me away! And I knew from right then on that I just wanted to take my guitar and learn a break like one of these bands. Then I started going to fiddlers conventions. I was about 18 years old, and that’s basically when I started playing bluegrass. From then on we’d get bands together and go play the fiddlers conventions. I played North Stokes, and Oak Ridge, and Union Grove—I went to every one that I could.

“I got my first job with the Lost & Found, and I played with them for a couple of years. Then I just got out of playing music. I didn’t think I would miss it, because I thought I don’t believe this is what I really want to do. I got to missing it bad, and I got to thinking, Wow, I wish I could play music again.’ Then I went to a party at Allen Mills’ house and Tim [Austin] was there. Tim came up and he said, ‘Man, I heard you sing.’ He wanted to know if I would be interested in joining the Lonesome River Band. I said, ‘Well, yeah!’

“Tim wanted to know if I could play bass. I said, Well I haven’t in a long time, and I don’t know if I could play the bass and sing at the same time.’ So what we decided to do was I played guitar and Tim switched over to bass—he didn’t care, he just wanted the band to work, and that’s what I wanted to do. But they sort of wanted me to play bass, and Tim had been the guitar player for eight or nine years. I just didn’t feel comfortable playing the guitar knowing that Tim was really the guitar player. So I started picking up the bass and trying to get through a song and sing it at the same time and try to do the bass beats on the beat. It was sort of tough for me. It’s something that I’ve really worked hard at doing, and I just try to keep it simple.”

Ronnie adds, “Really what excited me about the job was that he gave me some tapes. They had just done ‘Looking For Yourself,’ and I heard that and I thought, ‘Gosh, this is where it’s at. They have really come a long way from where they started.’ I loved that. He gave me a live tape of them performing. And I thought, “Wow! I really want to be in this band,’ because I know that people can make their records sound good if they put a lot of time into it, but these guys sounded good live, too!’

“I wanted to come into something where I could be involved with it and have a say-so about things as much as everybody else. It was a group effort and we were all about the same age. I was excited about being asked to join this band from day one.”

A few months after Ronnie and Sammy came aboard, Tim got the band into the studio. Only then did the full power of Dan and Ronnie’s vocal blend become apparent to him. He notes that, “I knew that we needed somebody strong to sing with Dan, but the combination of Dan and Ronnie’s vocals became a thing when we recorded. The first recording with all the guys in the band now was ‘Carrying The Tradition.’ ”

What the band discovered was that when two great singers come together under the right circumstances, they inspire and enhance each other. The whole truly becomes more than the sum of its parts.

“Dan makes me want to sing,” Ronnie declares. “It excites me. It makes me get into what I’m doing. It’s magic, almost, when I hear Dan sing. I really think Dan’s one of the finest singers in any music.”

“It wasn’t until Ronnie joined the band that I said, ‘Wow, we really need to go with it,’ ” asserts Dan. “With Ronnie’s vocal influence, it’s made me want to sing better.”

Sammy elaborates; “Even when Dan is singing lead on something and he goes to tenor and Ronnie sings the duet under him, you can’t tell! I mean, it’s like there’s two Dans there, because Ronnie is such a versatile singer. And so is Dan. Dan can sing any part and sing it well and change his voice to blend. In my eyes, they’re the best thing going, and I’m happy to be a part of their success. It excites me.”

Tim echoes that sentiment. “Ronnie and Dan have got a sound that we’ve all worked on creating. They are each different in their own way, but when they’re singing together, it’s just like one unit. The more they sing together, well gosh, they change parts and its sounds like they’re the same person.”

Part of the power of the Bowman/Tyminski one-two punch is that Ronnie’s rich baritone voice leans a bit more toward country, while Dan’s higher tenor cuts with a decided bluegrass edge. Together they combine the best of both worlds, giving the Lonesome River Band’s music tremendous vitality, accessibility, and appeal. Billy Smith’s “Hobo Blues” (from the “Carrying The Tradition” album), with its exciting vocal interchange, provides the perfect showcase for this spine- tingling phenomenon.

“Carrying The Tradition” firmly established the Lonesome River Band as the band to watch in the ’90s. The album was in the #1 slot on the Bluegrass Unlimited Top 10 Album Chart for six months, and was the International Bluegrass Music Association’s “Album Of The Year” in 1992. “Hobo Blues” was among the finalists for “Song Of The Year” as well. The band was a finalist for IBMA “Vocal Group Of The Year,” and if IBMA gave a Horizon Award, the Lonesome River Band would certainly have been a leading candidate.

The strength of “Carrying The Tradition” lay in its tasteful blend of new and old songs, of traditional and contemporary sounds seamlessly woven together, with the vocals of Ronnie and Dan at the forefront. Sammy explains how the album was conceived. “We went at it with the intention of doing a traditional record, because myself, with the Squires, and the Lonesome River Band prior to that had done more contemporary type stuff, and never really made our mark. We went at it in a traditional approach but enough of our contemporary personality rubbed into it that the young people still like it. It’s traditional, with more country-oriented vocals, and just a good combination; it just happened to be the right formula.”

An important part of that success formula is material selection and songwriting. Song selection has become increasingly difficult for bluegrass bands in the ’90s, since much of the great older material was rediscovered and recorded in the ’80s. There are few good bluegrass songwriters, and bands must often struggle to find enough original material to make a recording stand out in the competitive market. The Lonesome River Band has worked hard—with remarkable success—at including a significant amount of quality new material in its repertoire.

What does the band look for in a song? “Something that excites us when we first hear it,” says Tim. “It can be simple or it can be complicated. Usually when it’s real complicated, we try to make it simpler. A lot of songs have to hit us right away. Some of them we listen to a month later or another day and feel the song.”

In addition to conducting most of the band’s business, running his recording studio, and engineering the band’s recordings, Tim Austin has a publishing company, Doobie Shea Music, which publishes all the band’s original material.

Tim says that songwriting is a group effort. “Everybody’s involved in songwriting. There’s one song on the new record that me, Ronnie and Danny wrote, and that’s ‘She’s About Trouble.’ That’s the first time the three of us have ever collaborated on one thing. Ronnie wrote ‘Old Country Town.’ Then there’s other songwriters that we know, who are personal friends of ours, that are writing killer material, and nobody knows about it. They’re young people, they’re our age, so they’re influenced by our music, so in turn it shows up in their writing in a way.”

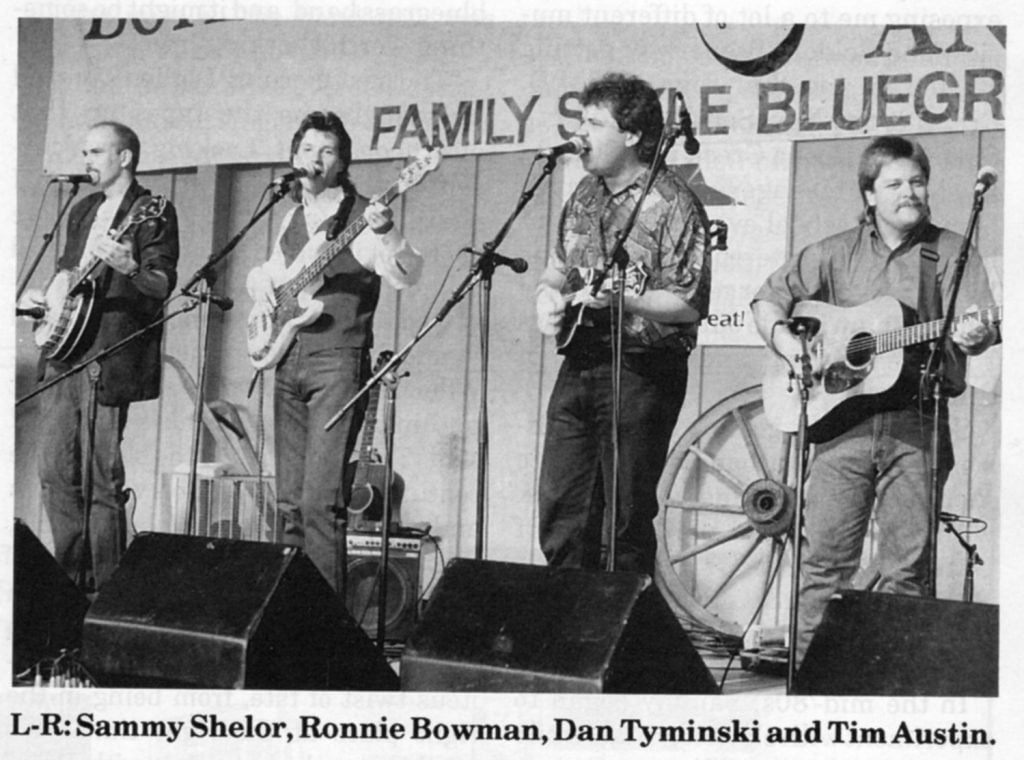

In separate discussions with each member of the Lonesome River Band about their music, one word appears repeatedly: “excitement.” Tim explains that this is no coincidence. “The whole center of what we’re trying to do is excitement. We want young people as fans so bad we can’t stand it. We want them to be excited about what we do, because we are. We feel that we can relay that message if we’re put in the right context.

“We were trying to play quality music, now we’re trying to entertain and play quality music, too. We try to change our songs so they don’t sound like the record. People say we sound as good live as we do on record, so we try to change a little bit to make them say, ‘Oh, where’d that come from, that isn’t on my record!’ And they like that.

“We’re on the right track,” he continues. “I see a lot of players coming into the studio that are telling us that all the kid bands are playing our songs, and trying to copy them down to the mistakes!”

Sammy adds, “We’ve established a niche for ourselves that is starting to pay off. We’re being talked about more than anything I’ve ever been involved in, which is exciting. That’s what we’re out to do, is excite people. When we hear them talking, we know they’re excited, which excites us, and just makes us want to get up there and give them the best show we can do.”

One of the most exciting developments this year for the Lonesome River Band is their new affiliation with Sugar Hill Records. Their new recording, “The Old Country Town” (Sugar Hill 3818), was released in January, 1994. Sugar Hill President Barry Poss feels that the Lonesome River Band will be a perfect addition to the label’s roster. “The heart of the Sugar Hill sound is contemporary music with traditional roots,” he says. “I can’t think of a band that fits that description better than the Lonesome River Band.” It seems fitting, indeed, that the Lonesome River Band should take its place on Sugar Hill beside Boone Creek, the band which first epitomized the “Sugar Hill sound” and first inspired the LRB’s members to play.

Poss continues, “They’re creative, they’re driven, they’re organized. All the essential ingredients for greatness are there. We’re incredibly excited about working with the Lonesome River Band.” Likewise, Tim says, ‘We’re glad to be with Sugar Hill. I feel like it was a good move. The first thing Barry told us when we met him, was how much he liked what we did.” Sammy agrees, “The Sugar Hill people are as excited about it as we are, and that’s what we like. We’re excited and dedicated to what we do, and we want the people we work with to be as excited and dedicated.” The band is anxious to get their new recording on the market, and generally feel that it will be their best ever. Dan proclaims, “I think it’s the best thing we’ve done. I think it’s a more emotional album than anything we’ve done so far. It hits me harder. The last album was, I thought, the best thing I’d ever had a chance to record on. Those feelings are back times two with this album. On this album, the songs excite me more, so I think it’s going to be really, really good.”

The release of the “Old Country Town” album marks the first time that the Lonesome River Band has released two recordings in a row with all of the same personnel. But it almost didn’t happen! In the spring of 1992, Dan Tyminski was recruited by Alison Krauss, and a few months later Sammy Shelor left to join country group Matthews, Wright and King, leaving Tim Austin once more facing difficult decisions about how to continue. Fortunately, Dan decided to return to the Lonesome River Band in September, turning what, for Tim, might have been a bittersweet IBMA Awards’ victory into a triumph.

Dan explains what happened. “The job with Alison came at a time when I was really trying to search for myself. I never chose to play bluegrass for a living. It was just kind of thrown at me. I’ve always done it because I loved it. Then after I moved away from home, got married, and realized, OK, bills have to be paid, I started looking at the industry as, what is going to be my best financial position, and let’s try to have it. I’ve had other offers that were better financially that I turned down because I liked the Lonesome River Band, but with Alison I saw the music more than anything. I was just dumbfounded by the band, I thought they were the greatest band, and I still do.

“It was such a big opportunity for me that I thought if I don’t take it, it may never come again. So I took it, and actually had the most fun I’ve ever had. That was one of the best jobs anyone could ever want. She plays great shows, the music is not just Alison with a whip and chain, it’s everyone putting in their influences, and everyone in the band individually really cares about how everything sounds. Weighing that with the idea that it was a good financial position, I said I can’t turn it down.

“The grass is always greener on the other side of the fence. After I took the job and things were really going great, I never thought I would be so lonely for the Lonesome River Band. I loved what we were doing and I loved the music we were playing, but the Lonesome River Band was more me than that job was. I just realized that I want to look back in ten years and know that wherever I am, I helped to create it. I think the Lonesome River Band is the answer.”

Sammy’s hiatus is a similar story. “Dan left, and the stress of not having what we’d had prior to that was really getting to me,” he recalls. “One day I just said, ‘Lord tell me what to do. I’ve done all I know to do, so just guide me where you want me to go.’ Two days later the phone rang, and it was Tony King, who used to be with J.D. Crowe & the New South. He was involved with a group called Matthews, Wright & King, on Columbia Records, and they were putting a band together, getting ready to go out opening for Reba McEntire. Here was something being offered to me, where I could go out and play my guitar, just be a hired hand, be paid well, and not have to worry about hassles. So I took the job, and was out with them from the end of July to the first of December.

“They didn’t have the success they had hoped for with their first record, so they had to take some time off to record another album and try to get some airplay happening. During the time that I was out with them, Dan came back to the Lonesome River Band. I had heard that, but I was happy where I was, and making a good living. It was a relatively easy job.

“It was kind of hectic,” he admits. “I didn’t move to Nashville, I was commuting from home, which was 400 miles each way. I would leave on Tuesday night or Wednesday night, drive to Nashville, meet the bus at midnight, ride to South Dakota or wherever, be out for four or five days, and then come back to Nashville, drive home, get home Monday morning, and leave again Tuesday night. When Matthews, Wright and King decided to take time off, Tim and the guys called me and wanted to get the old band back together. The more I thought about it, with Dan back, this is where I was really meant to be, so I came back.

“It all served a purpose,” Sammy points out. “It made us more dedicated to this band. Dan and I both went out and had other jobs, but we both realized that this is what we want to do and this is what we want to make happen. We’re in it for the long haul now. We’ve found our home.”

If desire and drive are the fuel for greatness, and talent and creativity the sparks that ignite it, this band is well on its way. With a renewed commitment, a new label affiliation, a hot new recording, and a new booking agent (Class Act Entertainment), the Lonesome River Band is poised on the springboard of success. And they can taste it!

“We want to win a Grammy,” Tim declares. “We feel like we could win a Grammy if we could get the right songs, in the right place, the right push. We want to play big shows. We want to work with country people. We want to work with all different kinds of music, really. We want to become a band that’s appealing to masses of people.

“If we change our music, we’re only going to go so far, because we’re going to be excited about our music. If we’re not, we’re not going to play it.

‘We’re not looking to change our bluegrass sound,” Tim maintains. We like playing traditional bluegrass music, and doing it our style. But if we’re offered an opportunity to have a big deal, we’ll work something out. And it’ll be another name, too. It won’t compete against our bluegrass. Maybe it could be like a Hot Rize deal—maybe we could come to a big festival and play our bluegrass and play our other music too, and just entertain everybody. Why can’t you do that? We’re against fences around what we’re doing.”

In addition to talent, creativity, dreams, and boundless energy, this band seems to have something much harder to achieve: a special kind of intuitive, emotional bond. “Everybody in the band has the same goal, which is really hard to find,” Ronnie attests.

Dan adds, “I feel fortunate that the four of us have found terms that we know that we can stay together and be there for each other. I don’t think there can be enough said about that. We all believe the same things,” he affirms. “We critique ourselves very hard to make sure everything is right. We all understand how the groove is supposed to be and we work off of each other. We all hear the same spots. When it sounds like there should be a ‘pow,’ nine times out of ten, we’ll all go ‘pow.’ That’s a rare thing. It excites me. When I get excited while we’re playing, I know that I’m happy with what we’re doing.”

Penny Parsons founded the Penny Parsons Company in 1991, specializing in bluegrass and acoustic music public relations and consulting, she also works as a freelance journalist / photographer, and as a regional sales representative for Record Depot distributors.