Home > Articles > The Artists > Lincoln Hensley

Lincoln Hensley

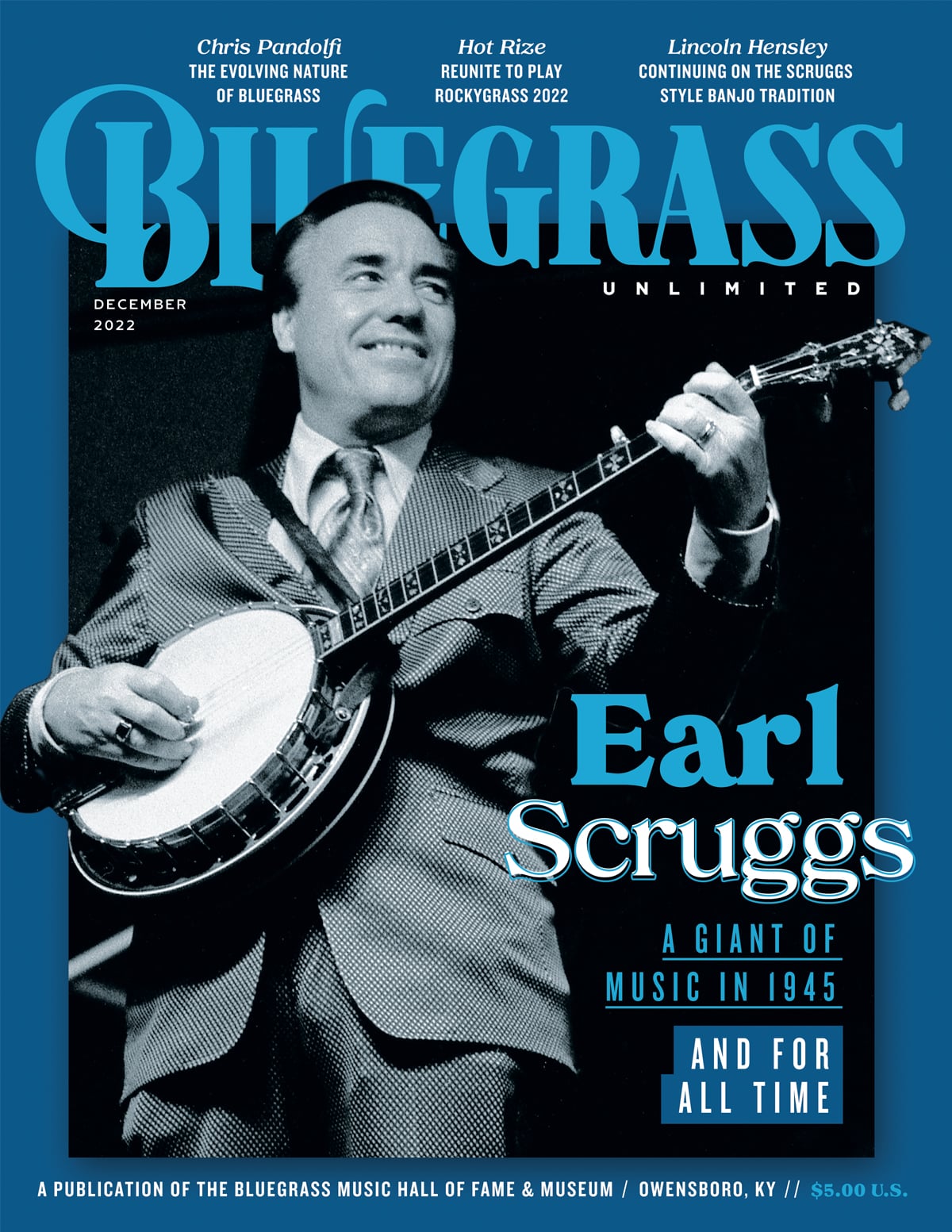

Continuing the Scruggs Style Banjo Tradition

Earl Scruggs helped define bluegrass music as we know it today and he originated the style of playing the five-string banjo that formed the foundation for banjo players in bluegrass music. Many banjo players feel that there has been no one that has matched Earl’s mastery of this style, however, they will point to players like Sonny Osborne, J.D. Crowe, and Bill Emerson as three banjo masters who came close. Now that those three banjo legends have passed, one might ask, “Are there any up-and-coming banjo players today who can continue the Scruggs style tradition?” I posed that question to a number of veteran bluegrass banjo players and a name that was consistently mentioned was Sonny Osborne’s protégée Lincoln Hensley.

Although still in his mid-twenties, Lincoln has made a name for himself in the bluegrass world, first as a student at East Tennessee State University (ETSU) performing in various ETSU ensembles, then with the Price Sisters and now with Billy Blue recording artists The Tennessee Bluegrass Band. His relationship with Sonny Osborne—starting when he was a senior in high school—not only included hours and hours of banjo lessons and conversations about all aspects of the music business—and life in general—but also having Sonny produce his upcoming instrumental album, starting a banjo company (KRAKO) with Osborne, and being selected by Sonny’s wife, Judy, to travel to Oklahoma in September of 2022 and represent her at Sonny’s induction into the American Banjo Museum Hall of Fame.

Lincoln’s Background

Lincoln Hensley grew up in Flag Pond, Tennessee, and still resides there. Flag Pond is located on the Tennessee/North Carolina border about halfway between Johnson City, Tennessee and Asheville, North Carolina. Lincoln’s maternal grandfather, who passed a few months before Lincoln was born, played the fiddle, banjo, guitar, harmonica, mandolin, piano, and upright bass (or as Lincoln says, “he played anything with strings”). His mother inherited the fiddle and although his father didn’t play music, there was usually a guitar and banjo at the house. Lincoln explained, “My dad, like a lot of people in the south, was always trading and swapping and bartering antiques and stuff like that. He got the banjo from a guy that he worked with. He either traded something for it, or the guy owed my dad some money. The guy built the banjo. It was a homemade deal and played like a fence rail. It was really hard to play.”

Regarding his introduction to bluegrass music, Lincoln said that his dad listened to bluegrass music and his paternal grandfather always had the AM radio in the car tuned to a station that played either country or bluegrass. Additionally, Lincoln’s uncle listened to bluegrass and was a guitar player. Although he heard the music around the house, Lincoln said that he didn’t pay a lot of attention to it until he heard that Earl Scruggs had passed in 2012. He said that when he heard about Earl’s passing, he started listening to the music and that “ignited a fire.” Lincoln decided that he wanted to learn to play the banjo.

Upon hearing that he was interested in the banjo, his uncle told him, “If you want to learn the banjo, there is somewhere that I need to take you and something that I want to get for you.” Lincoln said, “I think he did me the best favor that he could have ever done, and I don’t think still to this day he realizes what he did for me.” The place that he took Lincoln was the Birthplace of Country Music Museum in Bristol, Virginia. Lincoln recalls, “We went through it and he was showing me, you know, this is Mac Wiseman, this is Flatt and Scruggs, and this is Roy Acuff. When we got to the end of the museum there was a gift shop and he bought me a CD and said, ‘You take this and listen to it. This is how to play the banjo.’” The CD he bought Lincoln was Flatt & Scruggs’ The Complete Mercury Recordings. Lincoln said, “That was the only CD I had for the first year of my playing.”

The banjo that was at the house was a homebuilt model that was hard to play. Lincoln’s dad told him that if he could learn to play one song on that banjo on his own, he’d then pay for lessons. Lincoln set out to learn his favorite banjo tune, “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.” He recalls, “The only song that I wanted to learn at the time was ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown.’ I thought, ‘If I could learn that, then that is all I’d ever want to play.’ I didn’t know anything about slow downers. The only thing that I had access to was a black and white video of Flatt and Scruggs playing on the Opry playing ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown.’ I had that video and the original Mercury recording. There is a difference between the two, but that is all I had. I would watch that video and I could see where he was putting his fingers. I knew the concept of rolls and I watched his fingers to see which order the rolls were going in, forward or backward. Then people told me you could take a 78 record and play it at 33 and it would slow it down. So, I found a 78 of the recording and I did that for a while. It took me about a month to learn the first two verses.” That was enough for Lincoln’s dad to agree to pay for the lessons.

Unfortunately, Lincoln’s experience with his first teacher was not optimal. Lincoln said, “I started taking lessons at a local music store and later found out that my teacher didn’t even own a banjo. He was borrowing one from the store. That should have been my first clue. He was teaching me out of the Scruggs book, which I was thankful for, but after about the third lesson I saw the book on the counter and I thought, ‘I’ll get me one of these.’ I bought it and read ahead that week.”

In addition to purchasing the Scruggs book and working ahead of what his teacher had shown him, Lincoln also ran into a banjo player named Edison Wallin at a nearby cake walk pickin’ and Edison showed him two songs during the intermission. Lincoln said, “When I went back to my lesson the next week I had read ahead in the Scruggs book and had learned those two songs from Edison. I was showing my teacher what all I’d learned. I was kind of proud of myself and hoping that he would be too. But, he was not pleased because I think I had read into the book further than he had read. He told me, ‘It will take me three or four months to get you straightened back out.’ I said, ‘Well, I think this will be my last lesson.’”

From there Lincoln continued to work with Edison. He said, “Edison was a great mentor to me and he still is…he was up at my house last night and we picked some. He is a great picker and really got me on the right track.” Lincoln continued to learn from Edison throughout his high school years, with most of the lessons being conducted over a land line phone. He said, “I would hate to know the hours that I spent on the phone with Edison. He showed me a lot of the Scruggs catalog over the phone. I think that really helped me in a lot of ways…it was hard in the beginning because I couldn’t see what he was doing. But it made me really learn to use my ear.”

In addition to learning from Edison Wallin, Lincoln said that another thing that really helped him develop as a banjo player and musician was getting together with other musicians that were about his age. He said, “I would recommend to any young picker starting out that you find musicians your age to play with, especially if they are at your level or a little better. When I was in high school I had some friends that had started playing and they had started a bluegrass band. I came in after they had been playing one semester. They didn’t have a banjo player and had heard that I had started picking. I was shy and nervous, but they finally talked me into doing it. That really helped me. I had to learn a lot of songs pretty quick because they were already out playing shows.”

Because the banjo that Lincoln’s dad had at the house was so hard to play, Lincoln had started looking for another banjo to play after only a few weeks. He said, “There was a guy here in town that played a little bit and he loaned me a bottlecap banjo that played really easy. It was fine for what little I knew at the time. That was a big encouragement for me because it was much easier to play than the homemade banjo.” [Editor’s note: a “bottlecap banjo” has a cast aluminum rim and flange and the flange design has a bottle cap appearance.]

After Lincoln’s dad discovered how interested Lincoln was in the banjo, his father bought him a Flint Hill banjo, which was an RB-11 copy. Lincoln said, “I had seen some pictures of a really young Earl playing an RB-11, so that banjo stuck out to me because it had that star on the peghead. I played that banjo for about a year and a half. I then started buying banjos and trading and swapping around. From the git-go, every banjo I saw I looked at and evaluated whether I needed it or not. I became kind of a collector.”

Regarding his early explorations on the banjo, Lincoln said, “Early on, I played a little bit of everything. Edison was good at melodic style and he was also really big into Allen Shelton. He turned me on to Allen’s playing. He is still one of my top three banjo heroes. But, I was trying to play Bobby Thompson stuff, Bill Keith, Allen Shelton and I was starting to get a little bit into Sonny’s stuff, but I didn’t know much about him yet. Edison had listened to Sonny’s stuff, but he wasn’t as well versed in it.”

By the time Lincoln started his senior year in high school, he realized that “Earl’s right hand was the key to the whole thing.” He said, “I didn’t take it as serious as I should have in the beginning…not until I met Sonny. After I got to meet Sonny, that is when I started to be scholarly when I would study Earl’s playing.”

During his senior year of high school, Lincoln did not imagine that he would have an opportunity to go to college because he could not afford it. He said, “I had taken a lot of auto body classes in high school and I had gotten good at painting cars. So, I was going to try and get a job at the body shop in town after I finished high school. When you are a senior they have somebody come and talk to you about college. They asked me about my plans and I told them I’d probably get a job at the body shop, or maybe go to a technical school. When they asked me about my other hobbies and interests, I told them about the banjo stuff. They told me I should look into some scholarships. I got invited to apply for a scholarship at ETSU. It wasn’t through the music department, but it was through the honors program at the arts college. If you got it, it was a full-ride scholarship. They only gave ten out a year, not to just musicians, but to artists and photographers and stuff like that. I applied for it and I got it. I thought, ‘This is a sign that I should probably make a go of it.’ I went there for four years and got my degree.” Lincoln finished high school and 2016 and completed his degree at ETSU in 2020.

Lincoln Hensley and Sonny Osborne

Lincoln’s relationship with Sonny Osborne was initiated over the internet group Banjo Hangout during the end of his senior year of high school. Lincoln said, “I had really started getting into his playing, but he was so forward thinking and outside of the box that it is really hard to learn some of that stuff unless you have an inside source that is going to help you. So, I sent Sonny an email. I had got a six-string banjo because I found out that he had one of those. The high school band had started playing ‘Listening to the Rain’ and in that original recording of his he has a low note that you can’t get unless you have a six-string banjo. I didn’t know how he tuned that extra string, so the first email that I sent to him was about that. He told me, but didn’t give much other information other than ‘Don’t play one of those for very long because it will mess your right hand up.’ I started emailing him a little more, and a little more, and started asking him questions about his playing and asking him to show me this lick or that lick and he said, ‘The first thing that you need to do if you want me to show you anything on the banjo is get the Flatt and Scruggs album Foggy Mountain Banjo and learn that cover-to-cover, note-for-note, every lick and every back up note that Earl plays on that album. You have to know it and be able to play it in order. Once you can do that, call me and I’ll show you anything that you want to know.”

Lincoln spent six months working with that album every day after he came home from school. He said, “I’d work on that until I was so tired I just fell over. My mom tells stories about coming in and seeing me asleep on the bed with my banjo still strapped on me. When I finally felt comfortable with saying that I learned it, I sent Sonny an email and said, ‘I think I’ve got it.’ He called me directly and said, ‘Alright, play me Earl’s third break on ‘Sally Ann.’ Record it and send it to me right now.’ I had an iPad and made a video and sent it to him. He called me back and said, ‘Alright, what do you want to know?’ From that point, he was really great. He would show me anything and I could call him anytime.”

The first time that Lincoln had a chance to meet and talk with Sonny in person was at a regular lunch gathering that was held roughly once a month in Hendersonville, Tennessee. Lincoln had come to know Kenny Ingram and Kenny, a regular at the lunch, invited Lincoln to attend the lunch. Lincoln remembers, “The first time that I went there it was me, Kenny, Sonny, Gary Scruggs, Ronnie Reno, Eddie Stubbs, J.D. Crowe, Robin Smith and Larry Stephenson. I looked around and thought, ‘Why am I here? This is crazy! I don’t belong here.” But they were all so nice to me…Kenny and Ronnie Reno were the first to arrive and Ronnie was incredibly nice to me. He talked to me like he’d known me all my life and I had never met the guy. Stubbs was also really kind.

“Sonny was that last one to get there. Kenny had told me that Sonny could be a little harsh and could give you a hard time. But he told me to just let it roll off and not pay attention to it…just laugh and nod. Sonny came in and shook everyone’s hand but mine. He addressed each person and asked how they were doing and this and that. Once he got around to me, the waitress had come up to take the drink orders. You pay as you go into these places and Sonny said to the waitress, ‘You all gave me a senior discount. This kid over here is only twelve, does he get some kind of a kid’s discount?’ I was eighteen or nineteen at the time. Everyone laughed and I laughed, and Kenny leaned over and winked at me. From then on Sonny and I were friends. As I was going to my car I got my picture with him and he said, ‘You know, this stuff that I’ve been showing you on email is really difficult for me to type out. I only live about five minutes from here. From now on when we have these, why don’t you come over to the house afterward and I can show you some stuff. From there it got to be where I would go down there two or three times per month. Anytime that I had a weekend open I would call him and drive down to spend the whole day with him. I went to school for four years at ETSU, but I got my education from Sonny in Hendersonville…no doubt. I learned more there in his sunroom then I could ever learn anywhere else. It wasn’t just about the banjo either. It was about the music business, booking, how to dress, how to act, life, family…he is probably the smartest person I’ve ever met in my life. Not many people got to know that about him because he had to be ‘the Sonny Osborne’ when he was around people. But, when he got him by himself he was a different person. When you got him by himself, he was really an intellectual guy and he only had a eighth or ninth grade education.”

When asked if Sonny educated himself by reading books, Lincoln said, “Oh, yeah, that is what he spent most of his time doing. I think that because he had dropped out of school, he felt like he was somehow less than. A lot of people don’t know this. But he stressed it to me. He really wanted me to get that degree and he was hard on me about my college. He would ask me about my grades. I almost had to bring him my report card. If he thought that I was struggling, he would get on me about my classes. Anyway, I think that he thought because he didn’t have an education he was somehow less than, so he started educating himself by reading books about history and how to run a business…he was really a smart guy.”

After that first lunch with Sonny and the other bluegrass heroes, Lincoln had an open invitation to attend the regular gathering. He said, “Anytime that I could make it, I always went. There was always the same regulars—Sonny, Kenny, Ronnie Reno, and Larry Stephenson—but someone different would always show up. There were a couple where Skaggs came. Del McCoury and his boys came for a few of them, and Alison Brown. Paul Brewster was there for some and Bobby Osborne came to a few of them. You never knew who was going to show up. Sonny knew so many people and it just depended on who was in town. It was a good crowd every time.”

Of all the times that Lincoln met with Sonny, he only saw Sonny actually play the banjo one time. Lincoln said, “The one time I saw Sonny play was when we were in the studio and he was producing my banjo album. We were finalizing that album when his health started to go down. He was in my headphones while I was playing and there was a thing that he was trying to show me on ‘Sledd Riding’ and I just wasn’t understanding what he wanted me to do. He really let into me. He was saying, ‘Boy, that is the easiest lick. I don’t believe you don’t understand this. It is so simple.’ I stood up, got out of the booth, walked out there and said ‘If it is that easy, surely you can still play it and show me,’ and I set the banjo down in his lap. He looked at me like he could knock my lights out and I thought he was going to do it, and I probably would have deserved it.

“He looked at me and looked down at that banjo and said, ‘I haven’t played since 2003.’ I said, ‘I know. But if it is that easy, you can show me the pattern that you are wanting me to do on the right hand. He set his right hand down on the banjo head and played it right out of the gate. He said, ‘There! I haven’t played since 2003 and I can do that.’ Once I saw him do it, it made more sense. But that is the only time that I saw him play.” Lincoln recorded his instrumental album in 2019, but it has yet to be released. The hope is that it will come out sometime in 2023.

KRAKO Banjos

In addition to receiving lessons from Osborne about playing the banjo, the music business, and life in general, Lincoln also launched a banjo company with his mentor, which he continues to run with Sonny’s widow. The question is—How does a young man in his early twenties start a banjo company with a living banjo legend? Lincoln said, “Sonny built the first one out of old parts that he had in his garage and the first one had a Gibson neck on it. He called me one day and said, ‘I think I have enough stuff in the garage to build a whole banjo. I’m going to put it together and see what it sounds like. He did that and told me, ‘Take this thing and play it a while and see what you think about it. So, I come down there and picked it up and as I was leaving he said, ‘Take a piece of tape or something and cover up where that says ‘Gibson’ on the peghead.’ I said, ‘Do you want me to write something on it?’ He said, ‘I don’t care what you write on it.’ I’m sure that you have heard the story of Krako. He was the little demon that lived in Sonny’s banjo and caused all of the tuning problems. That is who he always blamed problems on if he’d break a string or go out of tune. He would blame it on a little guy named Krako that lived in there. So, to be funny I took black tape that blended with the peghead and then I took a gray Sharpie and I wrote KRAKO in block letters. The first show that I played with it, when I come off stage, there were three people standing there wondering where they could buy a KRAKO banjo.”

Lincoln called Sonny and said, “I think you might have something here. There are three guys wanting to buy one of these.” Sonny’s response was “You get their numbers and tell them that I will call them in two weeks with information.” Sonny then proceeded to assemble a team of people to produce the KRAKO banjo. At first, they built a prototype to see if they could match the sound of the spare parts banjo. Sonny worked with Greg Rich to design and produced a tone ring and Rich gave Sonny and Lincoln a contract for exclusive rights to the design. Lincoln said, “That is when the wheels really started turning because we put one of those tone rings in both of those banjos and it was lights out from then on.”

After the third KRAKO banjo sold, Sonny called Lincoln and said, “How would you like to be half owner in this banjo company with me?” Lincoln told Sonny that as a twenty-year-old college student, he only had about twelve dollars to his name, so he didn’t think he could invest in a banjo company. Sonny told him that his only investment would be to play a KRAKO on stage. Lincoln said, “We started getting orders left and right and quickly built a two-year waiting list. We had to cut off the orders because Sonny and I both decided that two years was too long to have people’s money. We quit taking orders just about a month or so before he passed.”

Lincoln said that he has worked hard to produce banjos for people on the waiting list and was able to get caught up on the two year list in almost a year. He hopes to start taking orders again in January of 2023. He said, “Right now, I have a list of sixty or seventy people who are waiting to get on the waiting list.” Since Sonny’s passing, Lincoln is now partnering with Sonny’s widow to continue the company. For more information, check out krakobanjos.com.

American Banjo Museum Hall of Fame

In January of 2022, it was announced that Sonny Osborne would be posthumously inducted into the American Banjo Museum Hall of Fame.

The museum director had asked Sonny’ wife, Judy, to travel to the ceremony and accept the award on his behalf, however, Lincoln said, “She wasn’t up for the flight out to Oklahoma. She didn’t want to get on an airplane. So, she asked me if I would go in her place. I said, ‘Of course, it would be an honor.’ I thought that I was just going to have to play, but when I got out there I realized that I was going to have to give a speech, and I’m not a good public speaker. But, it was really one of the highlights of my life to get to accept that for him because he did so much for me and he never charged me a penny for anything. I thought it was a very small thing to do to try to pay back the huge debt that I owe that guy.”

Last year Lincoln played for Greg Rich’s induction into the Hall of Fame and this year he and his girlfriend Aynsley Porchak (see Bluegrass Unlimited, September 2022) played one of Sonny’s tunes for the induction ceremony and Lincoln accepted the award with a wonderful acceptance speech on behalf of Sonny’s family. The entire ceremony can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZI5QHdyQxHM.

Lincoln On Stage and in the Studio

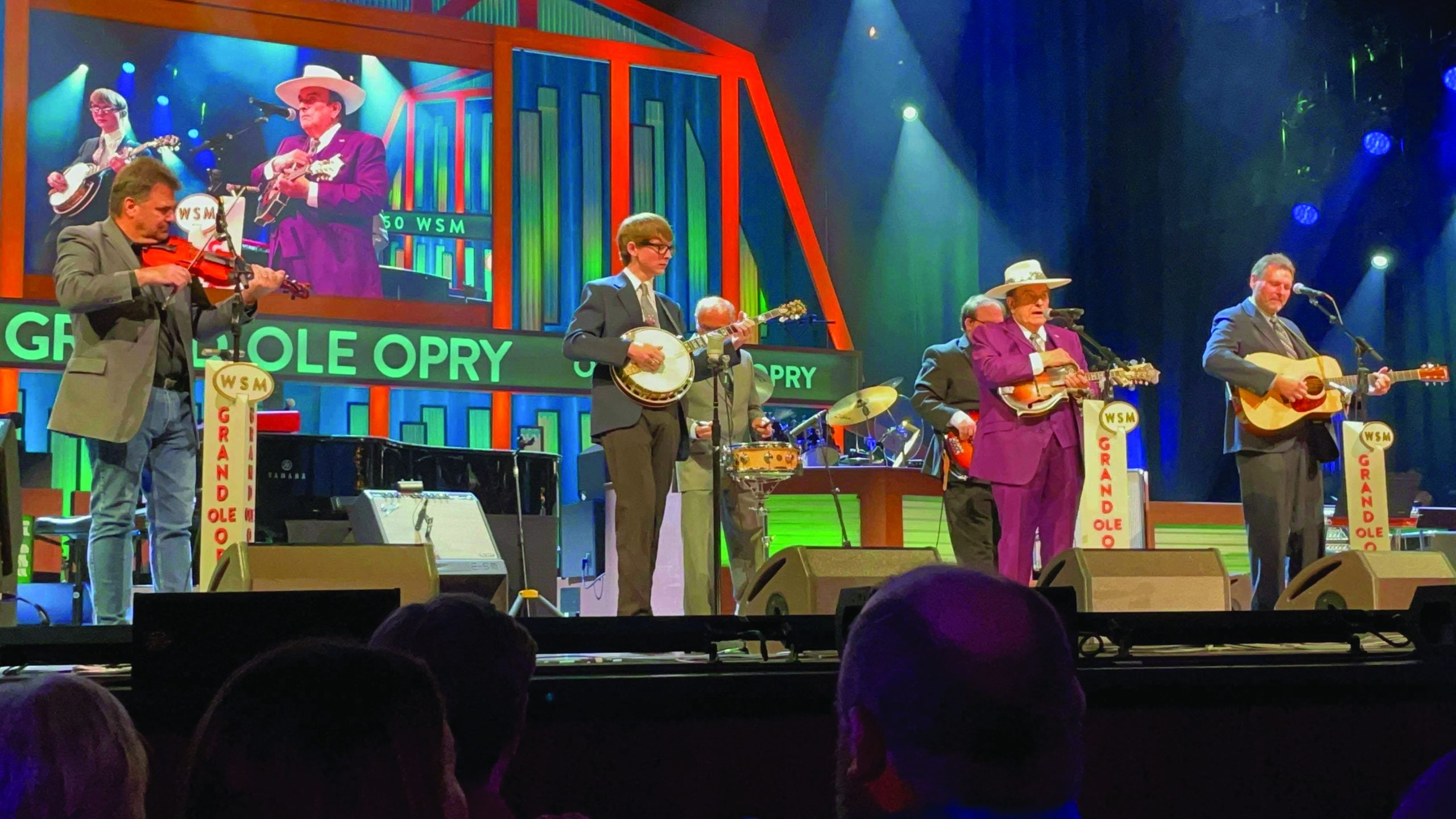

In addition to playing in his high school bluegrass band, performing with various ensembles while he was at ETSU, and occasionally filling in on banjo at the Grand Ole Opry with Bobby Osborne and Rocky Top X-Press (a gig that Sonny set up for him), Lincoln also spent about six months on stage with David Peterson and 1946 while he was at ETSU. Then, in 2019, he joined the Price Sisters and performed with them for a couple of years. He said, “They were great. I loved picking with those girls. They were super nice and they never told me how to play. They just let me do my thing. The first experience that I had really touring with a band was with the Price Sisters. Lincoln left the Price Sisters during the COVID shutdown.

In the spring of 2021, Lincoln formed a band with Tim Laughlin and Aynsley Porchak. They call it The Tennessee Bluegrass Band. Lincoln said, “I had left the Price Sisters and my girlfriend, Aynsley, had left Carolina Blue when that band broke up. We just needed work. There was a guy that was down here singing with us, so me and Aynsley and that guy and his wife and Tim Laughlin started the band. The guitar player and bass player left after about six months and we got the guys we got now.” [Tyler Griffith (bass) and Lincoln Mash (guitar)].

The band’s first album was released in the fall of 2022 on Billy Blue Records. Lincoln said, “When we first started, our five-year goal was to get on a really good record label and my personal goal was to get on Billy Blue because they are really doing a great job for their artists. We posted a video on YouTube of us singing and that night we got a text from Billy Blue’s A&R guy, Jerry Salley. He said, ‘Don’t sign anything with anyone until we can make you an offer.’ We got about six or seven offers within the first two or three weeks. It shocked us. We never thought anything like that would happen.”

The Tennessee Bluegrass Band’s Billy Blue Records release The Future of the Past debuted on the Bluegrass Unlimited album chart at number 12 in October 2022 and rose to number seven in November. This month it is number six. The future is bright for this band.

For a young guy, who has yet to see his twenty-fifth birthday, to have graduated from ETSU, spent years under the tutelage of the legendary Sonny Osborne, played as a sideman for several top-tier bluegrass bands, be the co-owner of a popular banjo company, and now be the leader (along with Aynsley Porchak and Tim Laughlin) of a new bluegrass band that is taking the bluegrass world by storm is quite incredible. The only thing left to say is that with Lincoln Hensley, the future of the traditional style of playing bluegrass banjo is in very good hands.