Home > Articles > The Archives > Images of Bean Blossom

Images of Bean Blossom

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

March 1985, Volume 19, Number 9

If it weren’t for a small road sign announcing the eye-blink of a town named Bean Blossom, we might have driven the length of Indiana’s Route 135 and never noticed Bill Monroe’s place. The memories come from 1978 but Bean Blossom seems timeless to me.

The sign marks what you might call the northern city limit, although, really, you could toss an apple to the southern edge. And across the road, near a gap in the fence, is a small poster, unreadable in the dark.

We turn up the driveway and left toward a ticket booth and an immense fat man spills out of an idling pickup truck to take our money and point to the woods. We have driven 12 straight hours, a couple of them through the carved, wet green of southern Indiana, and we are chilled by the night air, by the $55 tickets and by exhaustion.

But then our headlights illuminate a sight that reminds us what we came for, that drives exhaustion from our eyes, and stands as an omen for the week to come: Kenny Baker, at 4 a.m., walking alone in the moonlight.

We had heard a lot of bad things about Bean Blossom: too big, too wet, too dirty. And there were problems. The showers stopped working, the garbage piled up. And I’m glad I didn’t arrive on the hot weekend in search of a parking space. But my first Bean Blossom left mostly positive images.

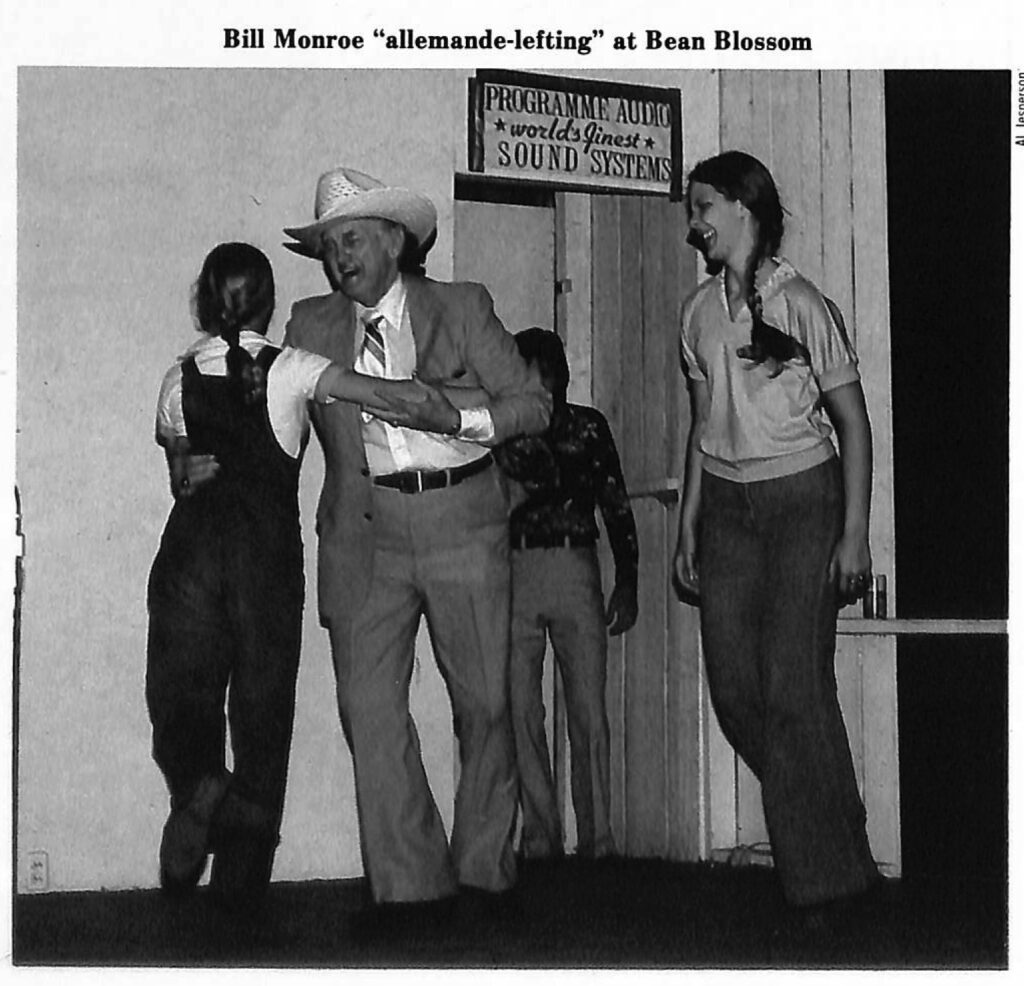

There was Bill Monroe, allemande-lefting his way around two girls one- fourth his age, grinning, stomping, clapping. And later, on his bus, taking a ribbing from a woman staffer for eating paunch-producing desserts. “The other women say I’m fine,” he shot back, winking.

After Bean Blossom I’ll never again think of Bill as that jut-jawed stone face that stares from his album covers. That is the formal Monroe, a portrait he dons before each show, as he looks out over the crowd, thrusts his chin forward, and sings.

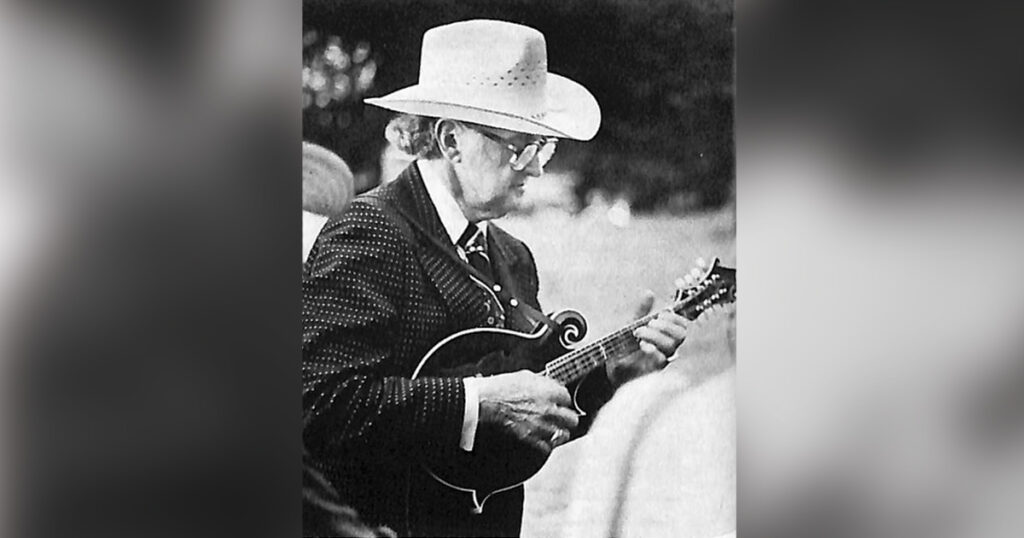

I’ll remember instead seeing Bill, at dusk, in a clearing left by a power line that crosses his festival-farm, doodling with a young man’s mandolin that had been offered him. A crowd gathered, and Bill talked and picked as he would to you or me on a porch, for nearly half an hour. Behind him the sun set, and the boy went off with both his mandolin and his soul aglow.

In that same clearing at week’s end, Bill generously posed for farewell pictures with fans. Somewhere I have a negative of Bill, immaculate in his suit and hat, with his arm wrapped around a friend, dark and scuzzy after a week with no bath, no sleep and no shave.

On stage, the Blue Grass Boys set the tone: flawless bluegrass played by masters. Two shows a day for more than a week. I can only admit now that sometimes I missed their show, to eat or just to stretch. How could I? Starved year-round for live bluegrass, and now turning away from it? It became sensory overload —too much of a good thing. I came back for the exhuberance of the new acts, the surprise of the Country Gentlemen, the rich good humor of Bill Harrell, and the last Bean Blossom for Lester Flatt.

It made me blue to see Flatt, pale and pasty, on a chair to stage right, almost as if he were not part of his own show. Each night as he neared the end, he turned ever so slowly, got up and walked offstage as if his D-28 were an anvil with a shoulder strap. Each performance brought a lump to my throat as the crowd, seeing him shuffle off, roared its respects, and, as it turned out, its goodbye.

Through camp, the aroma of Priscilla’s cinnamon rolls mixed with corn dogs and fried onions. At night, there was the hint of pot, smoked as casually as most of us swig beer, and in the same places.

There was jamming for every player at every level. A friend probably will tell his grandchildren about the night he jammed with Kenny Baker and Bob Black because he was the only guitar player in the crowd who knew the chords. There is no prouder moment in parking lot picking than the moment when someone asks you to sing, again, a song you spent hours learning last winter.

I also remember the 3 a.m. shivers I got, not from the cold, but from Wayne Lewis’s voice as it cut through the night from a distant campfire. As piercing and soothing as a train whistle, he sang forgotten songs long after I drifted off.

We got little sleep that week. But that’s not what we came for. We came for the music and the people and the emotion-simple and real—of a bluegrass festival. We found it at Bean Blossom.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I had a similar experience there when we visited the show in 1976. Lester Flatt looked in such poor shape. Bill and Wayne Lewis walked among the crowd between shows. It was my first bluegrass show. My brother and I drove 7 hours to get there from Michigan.