Home > Articles > The Tradition > IBMA Hall Of Famers Remembered

IBMA Hall Of Famers Remembered

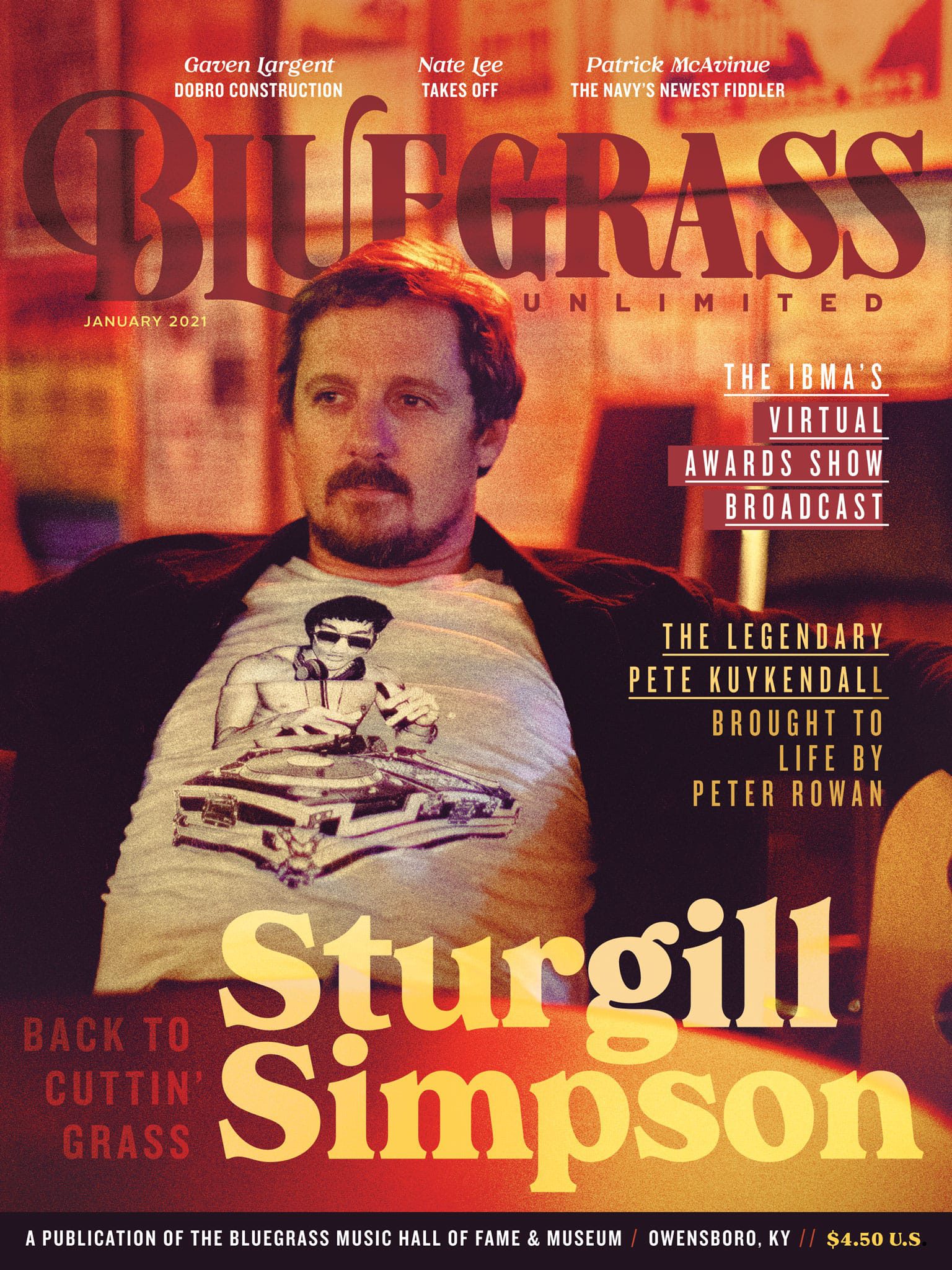

The Legendary Pete Kuykendall Brought To Life By Peter Rowan

When it comes to featuring artists who are honored at the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum, located in Owensboro, KY, our goal here at Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine is to look deeper than what you may read on their wall plaque. We will continue to seek out the unique personalities in the IBMA Hall of Fame and dig into what makes these amazing musicians tick, if they are still with us, or to illuminate their lives through interviews if they have passed on before us. Pete Kuykendall is a perfect example of someone who led a life that was interesting and passionate as well as historic.

Kuykendall was inducted into the IBMA Hall of Fame in 1996, and his official wall plaque touts him as one of bluegrass music’s earliest historians, as a festival promoter, a music publisher, a bluegrass musician, co-founder and long-time publisher of Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine, and one of the many involved with the creation of the International Bluegrass Music Association.

Kuykendall died in 2017 at 79 years of age of diabetes and dementia. After beginning to write for Bluegrass Unlimited in 2004, this author experienced over a decade of moments with him, offering ideas and listening to his stories. Ultimately, however, that is how most people remembered Kuykendall, as an older gentleman sitting in the Bluegrass Unlimited booth at the annual IBMA World of Bluegrass Convention with bluegrass stars and up-and-comers stopping by to hopefully sit beside him for a few minutes to visit.

In his younger years, however, Kuykendall’s musical abilities were impressive and exciting and his involvement in the growing bluegrass music industry was dynamic and institutional.

In this article, we will pick the brain of a bluegrass legend who knew Kuykendall back in the day, before Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine was a glimmer in anyone’s imagination.

Peter Rowan, the “Lion of Bluegrass Music,” is now in his late 70s. That means he was around when many of the First Generation bluegrass stars were still in their prime. In 1963, Rowan became a member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, a tale that is well-known. One day, in the middle of a run of shows, Monroe wanted to take a detour into the fervent Washington DC bluegrass scene to see a group performing at a club called The Shamrock. The experience would affect Rowan for the rest of his life as the music he heard that night blew his mind.

Washington DC is where bluegrass music went “uptown” in a sense. With the Great Migration of the 20th century, folks from the southern states and the Appalachian Mountains travelled north and east looking for good jobs and a better way of life. They brought their music with them.

Kuykendall grew up in the DC area and became an acclaimed multi-instrumentalist who enjoyed many different kinds of music before falling in love with bluegrass. He played with local DC legends like Buzz Busby and was a member of an early version of the IBMA Hall of Famers the Country Gentlemen.

Rowan, on the other hand, grew up in the Northeast where bluegrass music had also established a foothold. Still, after a college year has ended, a young Peter Rowan wanted to experience this new music that he fell in love with closer to its origins, so he hit the hard road with his thumb out and a pack on his back to get closer to the origins of bluegrass.

“When I left school, I hitchhiked from Hamilton, NY, down to Washington DC,” said Rowan. “I met many folks when I was at the Galax Old Fiddler’s Convention in Virginia where I was backing up a young girl named Gloria Belle, who ended up playing with Jimmy Martin. So, I had made forays into the South around 1962, a year before I returned as a member of Bill Monroe’s band. When I got to DC the first time, I walked into the Shamrock Bar and there was the Country Gentlemen playing inside. It was total magic as the first sight I saw was of Charlie Waller hammering a great big ole’ guitar G-run on his D-28 on a single microphone setup, holding the guitar up to it and doing the whole thing. I had been listening to their records and I was particularly interested in this beautiful articulation that Charlie had when he played those runs, and I was trying to learn all of that. I got to meet those guys then and they were all very friendly.”

After making friends in DC, Rowan found himself in another club a day or two later, watching yet another local DC band. That is when he first saw Pete Kuykendall onstage.

“Jack Tottle (who would go on to create the bluegrass program at East Tennessee State University) and others befriended me and took me to a place to hear a musician named Smiley Hobbs,” said Rowan. “Smiley Hobbs was a multi-instrumentalist and when we walked in, Smiley was playing the mandolin, and in his band was a guy named Pete Roberts, which was the stage name at the time of Pete Kuykendall. Pete was wearing slacks with a white shirt and his sleeves rolled up. Up north, I had been listening to an album made by Mike Seeger called Mountain Music Bluegrass Style that featured Smiley Hobbs on it along with Earl Taylor, Tex Logan, Don Stover and all of those guys.”

After making that connection with the South, Rowan returned north to finish his schooling at Colgate University before travelling to Boston to play gigs at the Hillbilly Ranch with the Lily Brothers. Soon after, at the behest of friend and future IBMA Hall of Famer Bill Keith, Rowan became a part of Bill Monroe’s group the next year in 1963.

Now based in Nashville, Monroe and his new guitarist Peter Rowan traveled north for gigs and made their way to the bustling DC area once again.

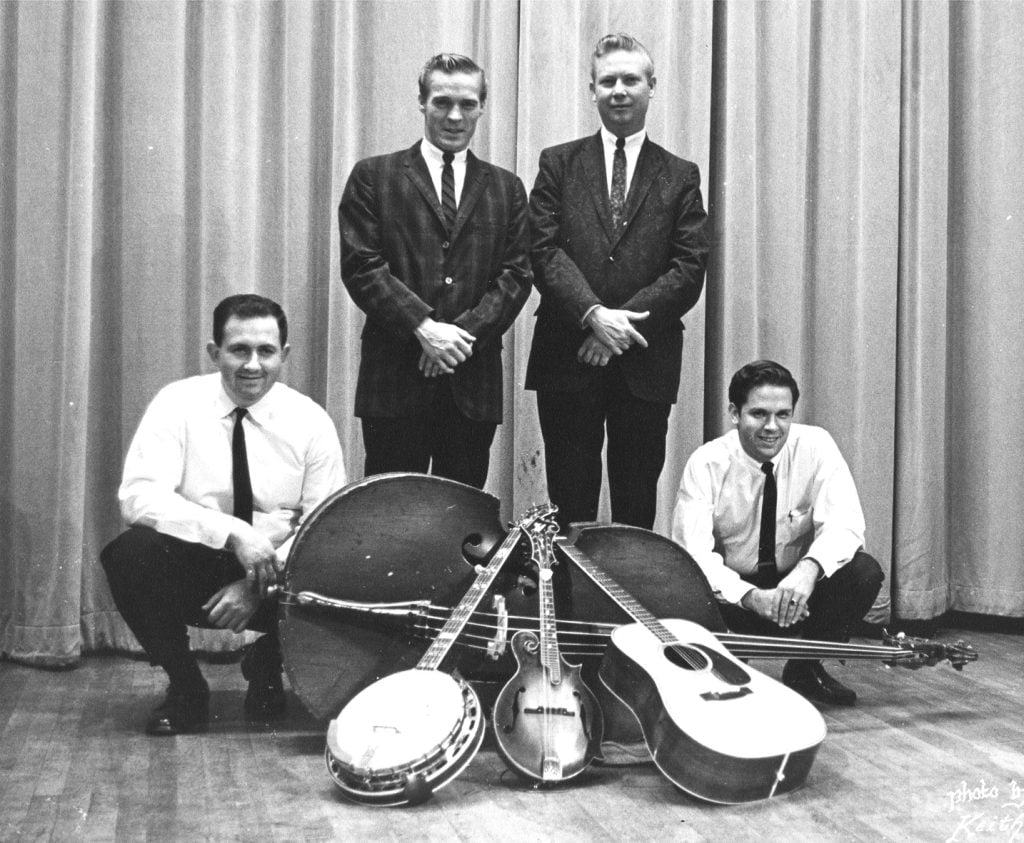

“What I remember is when we came there, Bill and I double dated,” said Rowan. “He dated somebody named Joan and I dated someone named Alice. It was just about companionship. So, I stayed in town longer and at one point, we decided to go to the Shamrock because we heard that Red Allen was going to play there along with Scotty Stoneman. We went to the club and the band featured Red Allen on guitar and vocals, Scott Stoneman on fiddle, Pete Roberts (Kuykendall) on the five-string banjo, one of the Yates Brothers on bass and Frank Wakefield on mandolin. When I saw this band at the peak of their powers; that was my full introduction to the musicality of Pete Kuykendall.”

It is an exciting memory that Rowan still savors over five decades later.

“For me, I was just getting to know everybody when I saw this band,” said Rowan. “Walking into the Shamrock that night and seeing what I viewed as the legends of the DC sound, after hearing the roots of the DC sound on those Starday label records, I was still learning how to play my art and they were just playing it straight. To be one of the people in the audience that night, and it was a moderate crowd, these guys were playing for the fans and it was like, ‘My God!’ We became bowled over by their authenticity. Pete was at his banjo peak, and Red was in his element in his partnership with Frank Wakefield. I think David Grisman recorded them at one point for Red’s album on the Folkways label.”

That evening would find Rowan beginning a long friendship with Kuykendall and the experience also gave added strength to Rowan’s own music evolution.

“To pick a word, the aura around those guys that night was not of second-rate bluegrass music,” said Rowan. “It was the local, authentic and powerful bluegrass that centered on DC and the Starday record label connection and they were totally in their element. The weight and the gravitas that they put into their music was not superficial. They were playing bluegrass music to the very deepest aspect of the genre that they could go. It wasn’t overly rehearsed. It was just that everybody knew the material. So, beyond Bill Monroe, my idea of bluegrass music was what these guys were bringing forth. To finally see them while I was working with Bill Monroe just knocked me dead. And, that is how I got to know Pete.”

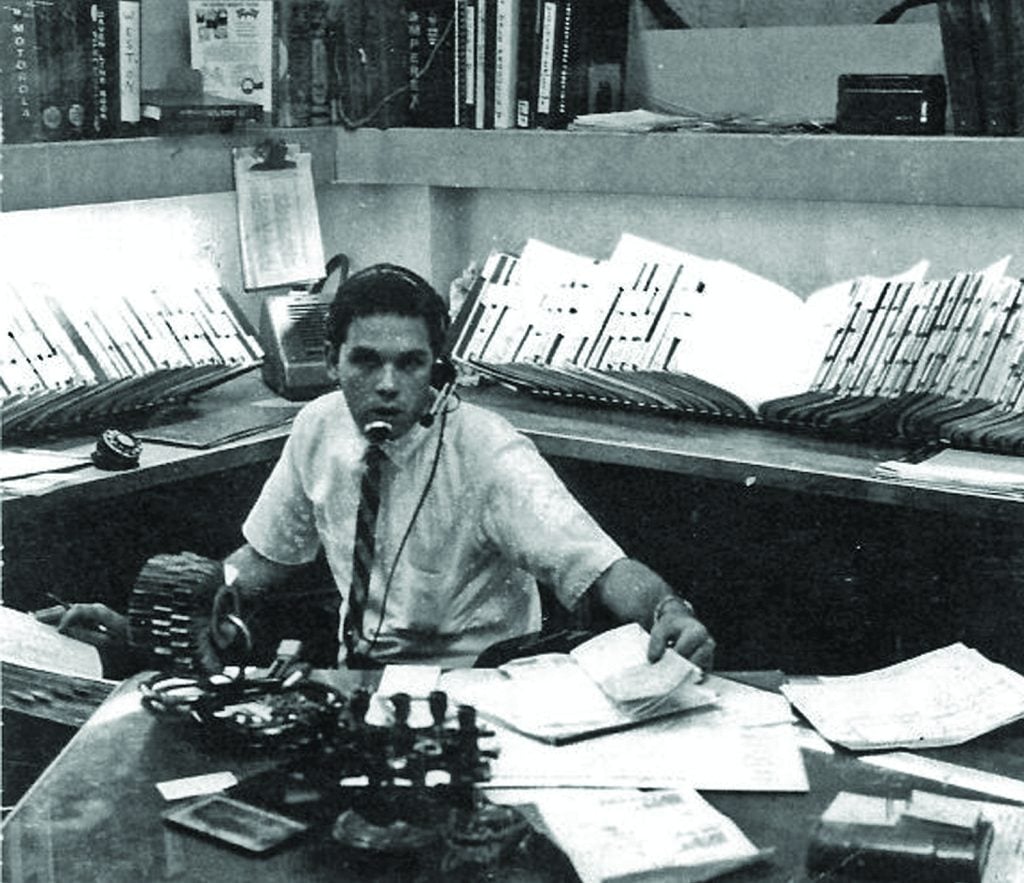

In his younger years, Kuykendall was a music and engineering nerd in the best way. He became a DJ and learned the engineering side of recording music and doing radio broadcasts. He even built a recording studio in his home long before it became the cool thing to do. He recorded music by Mississippi John Hurt and other nearly-lost country blues performers. Kuykendall also worked with the Library of Congress and formed his own publishing company called Wynwood Music, where he made sure songwriters got royalties for their songs that were recorded by others.

Frank Wakefield, Red Allen, Pete Kuykendall.

As for Rowan, in the next five years after leaving Monroe, he was in the bands Seatrain, Earth Opera and Muleskinner before forming the very influential Old and In The Way, featuring Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, David Grisman, John Kahn and IBMA Hall of Famer, Vassar Clements.

“The Rev. Robert Wilkins wrote a song called ‘Prodigal Son’ and the Rolling Stones recorded it, and they put their names in the credits as the songwriters, which is done a lot in the music business,” said Rowan. “Pete had my respect for getting Wilkins’ his proper royalties, and he did it for Skip James as well. Pete got the royalty money to the artists and to their families. So, it is pretty amazing that Pete got royalties recovered from a band as big as the Rolling Stones. People don’t know or realize this, yet Pete Kuykendall was a monster in the music business back in those days.”

In the mid-1960s, Kuykendall along with Dick Spotswood, Vince Sims, Dick Freeland and Gary Henderson created the then-newsletter known as Bluegrass Unlimited. By 1970, the publication had become a full-fledged music magazine with Kuykendall at the helm.

“Kuykendall and Spotswood always revered what is the real thing about bluegrass music,” said Rowan. “One year, myself and my brothers Chris and Lorin were on a tour, working a record we had put out together, and we came up from Nashville to a venue along Long Hollow Pike and we sat in with Bill Monroe. Charles Sawtelle of Hot Rize was there, too. We were up there for 15 or 20 minutes or so, and Bill was on fire. He never did anything half way. At that time, Bill was still in good voice and everything. After that, we drove up the East Coast and had supper and spent the night at Pete Kuykendall’s house. That is when we got more into the history of the music. He brought out all of these recordings and he’d play a big vinyl record and say, ‘That’s my D-28 you are hearing on there.’ Pete played bluegrass music. Pete loved bluegrass music. Pete loved being the Editor of Bluegrass Unlimited.”

Rowan would see his friend later in life when age and other factors were wearing Kuykendall down.

“After Pete got sick, I would still see him,” said Rowan. “He would show up and I don’t know what started this, as it may have been his ailment, but he started talking to me like, ‘We are in on it. We know the truth here. You are like Hank Williams. You have got to be careful and not go off the rails here.’ He was being a bit of a mentor, which was very sweet.”

While Kuykendall believed in the true nature of bluegrass music, he was not a snob to those who tried to put a new spin on it. He was always good to bands like Sam Bush and New Grass Revival and others. Andy Falco of the Infamous Stringdusters will tell you that Kuykendall would tell him early in the band’s history that, ‘Yeah, you guys are a little bit off the rails, but we still love you.’”

“Pete was about keeping the whole bluegrass ship afloat,” said Rowan. “He wasn’t about just one sail on the ship. He was like, ‘This is Bluegrass Unlimited.’ He interviewed us early on. By the 1960s, with the first generation getting older, it was exciting to have a bluegrass band full of 20 year olds, and he picked up on that. And, back then, you would have to find out about an upcoming bluegrass festival or even a bluegrass show by phone, the so-called ‘bluegrass twang telegraph.’ How did the word get out about Roanoke, the first bluegrass festival in Fincastle, Virginia? The festival may have put an ad in a folk music magazine or something. But, that is what started the whole ball rolling as Bluegrass Unlimited started about a year later and, thankfully, filled that niche and desire for bluegrass music information.”