Home > Articles > The Archives > High Country

High Country

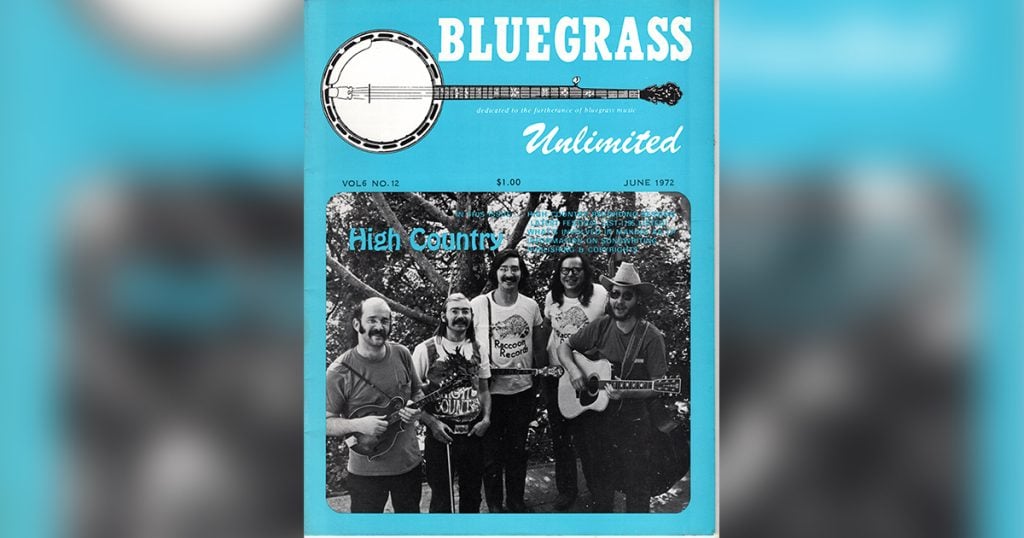

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1972, Volume 6, Number 12

The place looks like a composite of all those little Nashville recording studios you read about in Look or Newsweek, once a garage or spare bedroom and now a down home hit factory where the new sound of today’s country music is put down.

But Raccoon studio B is a bit funkier than most, looking more like a former chicken coop than a remodeled garage. It’s in the town of Inverness, California, a few miles up the Pacific Coast Highway from the wide spot in the road that gave its name to the parody, “Hippie From Olema,” which the nation’s more hip rock stations played a lot in the wake of Merle Haggard’s “Okie From Muskogee.”

Inside, there is an old Coke cooler, a Sho-Bud pedal steel tucked into a closet/anteroom with shelves of tapes, and a chromium forest of microphone stands with the required spaghetti-like tangle of cords trailing across the floor and along the ceiling and walls and through a partially open aluminum-framed sliding window to the control room.

Behind the window sits a custom made eight track control board, miniaturized into a surface only about three feet square.

And behind that, sitting in a chair and twirling knobs and flicking switches, is “Banana,” a member of the Youngbloods rock band and the producer of High Country’s bluegrass albums for Warner Bros./Raccoon.

Banana is an excellent 5-string banjo picker and a collector and trader of old instruments. He is the person who spotted High Country on a local television program, phoned them and arranged to record their first album. Today’s session is to finish up the group’s second disc, “Dreams,” which has just been released. (Warner Bros. (Raccoon BS 2608.)

The Raccoon sticker on the album jacket means the master tapes were made at the Youngbloods’ Inverness studio then pressed and distributed by Warner Bros.

Behind Banana and to his right is a 3M Series 400 eight-track tape recorder, which makes possible the high quality of sound on Raccoon albums. It stands about five feet high in its own cabinet and uses recording tape an inch wide.

Banana is just sliding one of the reels out of its cardboard box and threading it onto the machine. “It costs about $40 per roll,” he says. “That’s if you buy in quantity. If you buy less it costs more.”

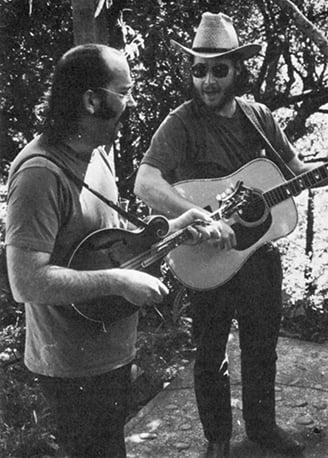

Outside the control room Butch Waller, Ed Neff, Chris Boutwell, Bruce Nemerov and Elon Feiner have arrived, shed coats, opened cases and begun tuning up.

The instruments have been riding in car trunks for some time, and they are cold and tricky to tune, but eventually everyone is together, (“close enough for jamming” comes the inevitable cliche from somewhere, which belies how seriously the members of High Country take their music) and the sounds of five people practicing five different songs simultaneously begins. Ed on fiddle and Butch with the mandolin get together first, practicing their duet on the traditional “Little Rabbit.” Others play snatches, stop to tune, then play again.

Banana is running a special test tape which allows him to set up the control board to the standards of the National Association of Broadcasters. This takes about ten minutes of listening to various beeps and tones and setting the equipment so the gauge needles go where they are supposed to. Finally, he announces, “Gentlemen, we are in alignment. Now let’s take some levels.”

Ed Neff is first. “Play a hot lick,” Banana says.

“Do you want the $2 lick or the $4 lick?” asks Ed, raising his fiddle to the mike. As the chuckles die down (there are a few non-musicians in the room; Jerry Long, the band’s manager, a few friends of various people and me) Neff rips off few fiddle runs until Banana is satisfied.

Watching the growth of Ed Neff as a fiddle player has been an exhilarating experience for bluegrass fans in the San Francisco area.

When I first encountered the band, not quite three years ago, Neff was already a competent fiddler, but I remember thinking he lacked confidence, played too softly. But today, Neff’s fiddle is a soaring musical delight, effective both on solo and backup work and a strong underpinning of High Country’s sound. His dexterity is remarkable, yet he never sacrifices tone for speed. The 50 or so people who were at a bluegrass party in of all places, City of Industry, California, after last summer’s Topanga Canyon Fiddler’s Convention, were treated to probably the best fiddling on the West Coast in some years when Byron Berline and Neff gave an impromptu double fiddle concert that left the audience as wrung out as the musicians.

Neff was born in St. Louis and moved to Elsinore, a community in the Southern California desert in 1961, when his father got into a business reclaiming silicon carbide from a local toilet factory and selling it to quarries as an abrasive for wire saws.

Elsinore was not one of the world’s lusher garden spots, Ed recalls. “It was 100 degrees and dusty. The dust would blow off the lake (Lake Elsinore is a vast, dry lake) so bad you had to have your lights on in the daytime when you drove down by the lake.”

He played flute and string bass in high school and got into guitar when the Kingston Trio sparked off the 1960s “folk boom.”

“I started playing Peter, Paul and Mary stuff, and Kingston Trio things, and I started hanging around with a bunch of folk types in San Bernardino playing New Lost City Ramblers Music and some bluegrass,” he said.

“I played in the Atomic Steam Ratchet String Band, doing old-timey music,” Neff recalled. “We had great posters, better than the band.”

Ed moved to Northern California and began playing the mandolin at a place called Don’s Red Barn in the Mission District of San Francisco. “It’s the kind of place where everybody goes to get drunk and fall off bar stools,” he said. “I was working for the railroad at the time. I’d work until 10:30 then go play until 2 a.m., then go to a jam session until dawn, then take a nap and go to work. He moved into the fiddle from the mandolin and was playing with a group called Styx River Ferry when Butch Waller asked him to join High Country in 1969.

When Neff finishes his $4 lick, each member of the band plays and sings a bit to get their own levels set, and Banana says, “Okay, now play something together.”

Somebody suggests “Bill Cheatham” and suddenly the room is filled with the rollicking sound of the old fiddle tune.

Banana’s control board is a magnificent device which will do so many nifty things that it seems Banana has a hard time keeping his fingers off the switches. The touch of a button isolates any instrument, and each track has tone and volume controls and heaven knows what all else. It looks like the inside of Apollo 16.

Checking it out, Banana goes from instrument to instrument, listening a moment and then flipping back to the whole band.

“The bass sounds terrible by itself,” he says, pushing the button on Elon Feiner, “but you can hear it. If it sounds good by itself you can’t hear it in the whole sound. That’s one thing we discovered in our massive tests. There’s nothing I like better than a massive test.”

Banana turns his attention back to the studio, where the band is loose and ready to cut a track. First on the list is “Little Rabbit,” an old fiddle tune with a distinctly Scots-Irish flavor. It starts with an unaccompanied duet, just Butch’s mandolin and Ed’s fiddle, then about halfway through the other instruments join in.

That’s the plan anyway, but Butch and Ed blow two takes (“Damn, let’s start again … ”) before a good one is on the tape.

Banana plays the good take back and everyone listens and approves. “Okay, we’ll keep it,” he says, and prepares for the next take.

Slipping the leather strap of his F-5 over his shoulder, Butch Waller returns to his microphones. Bom in San Francisco and raised in Berkeley, Butch began playing guitar, “Everly Brothers stuff,” when he was eleven years old, with banjoist, Herb Pedersen, who later was a member of The Dillards.

One night about a year ago, High Country was playing at Berkeley’s Freight and Salvage Coffee House when a patron presented Butch with a yellowed clipping from the local Berkeley newspaper with a smudged photo of the Waller-Pedersen duo and a caption something like “Berkeley’s own Kingston Trio …” which earned Butch any number of jibes from the band in the following weeks.

Waller began playing mandolin in 1963 with a group called the Pine Valley Boys. He is the only original member of High Country, which in the beginning consisted of himself and Myles Sonka. In 1968, Sonka was injured in an auto accident and Rich Wilbur (now with California Express), David Nelson (now with New Riders of the Purple Sage), Rick Shubb on banjo and his wife Markie on bass, joined. Others who played with the band during its early years were Peter Wernick (now of Country Cooking) on banjo, fiddler Andy Stein (now with Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen) and Chuck Wiley, now bassist for Styx River Ferry.

The band finally stabilized with the present personnel except for Rich Wilbur on guitar, until just before the band’s first record was made last year. Wilbur did much of the singing on the first album, since Chris Boutwell was new with the band at that time.

Most of the vocals on “Dreams” are by Chris, who is correcting a minor tuning flaw in his D-41 before the next song, which is to be “Sitting Alone in the Moonlight.”

Wonder of wonders, the first take is good, and they get ready to do “Dreams,” the title song of the album and a possible 45 r.p.m. release. The song has been running long, and the band begins to discuss how to trim it — eliminating breaks and substituting turnarounds. They try the changes a few times, and satisfied, signal Banana.

Chris does the verses, with Ed and Butch joining in for a three-part chorus. It’s tricky to do just right and several takes are required before an acceptable version is on tape.

Chris is glad to be done with it, as the song is at the top of his vocal range and not easy to sing. He is a Southern California boy who began playing old time country music on guitar as a junior high school student.

“I met Ed Neff and we played together off and on at supermarket openings and that sort of thing, and at the Penny University in San Bernardino,” he recalled. “The first bluegrass I heard was the Hickory Stump Marsh Marmots — they weren’t bad.”

“Then I went in the service. By then I had decided that bluegrass was what I wanted to do, but I couldn’t do it by myself in the service, so I did country/folk, Ian and Sylvia stuff.”

Back in civilian life, Chris got a job as a machinist, but was laid off, fortuitously just in time to receive a phone call from Neff asking him to come north and join High Country. When he isn’t picking and singing, Chris is into leatherwork, and has one of the more elaborate guitar straps you’ll ever see.

Bruce Nemerov, High Country’s banjoist, is a native of Minnesota who came to California when he was 15. Originally a piano player, he turned to stringed instruments when the folk music thing came along in the early ’60s.

“I didn’t know anything about banjos,” he smiled in recollection, so I went out and bought a tenor banjo and then sat down and tried to figure out why it didn’t sound like the 5- strings I was hearing on records.”

After finding out about his missing string, Bruce went out and bought a $50 Kay 5-string and sat down with his record player to learn how to play it.

He played with Neff around the San Bernardino area and was with Styx River Ferry before joining High Country. A high point in his career? “I’ll always remember the Red Barn,” he smiles.

Elon Feiner, who plays bass and does an occasional vocal, is a Los Angeles native who came to northern California about 10 years ago. He has been a long-time guitar player but only began playing bass when he heard High Country needed a bass player.

“I had never been a bluegrass musician before, but I had been on the fringes of it and I knew most of the old bluegrass standards. I’m probably the least bluegrass freak in the band.”

That’s not a surprising statement in view of Feiner’s first musical venture, the “Players Tambor,” a Jewish folk dance troupe in Los Angeles. Later he did a lot of playing in coffee houses and such, but High Country is his first attempt to make a living as a musician. In other times he ran a record store in Los Angeles, worked as a photographer, in a recording studio and in a motorcycle parts house.

Besides the bass, Feiner’s interest is in sound, and he manages the mikes and sound system for the band.

“It’s important to have as good a sound system as we can get,” he says. “We play mostly to non-bluegrass audiences, and they tend to hear the band sound as opposed to listening to the individual instruments as a bluegrass fan might do. They get on the energy trip which they can appreciate.

“We play mostly rock audiences and get a real good reception. Bluegrass Unlimited readers shouldn’t be so paranoid about the rest of the music world.”

“Some guy from Texas,” he laughed, “bought our record from a mail order place but then he sent it back. He said we sounded okay but he didn’t like the way we looked on the record jacket.”

With “Dreams” on tape, it’s about all over but the shouting. Banana switches tape reels to get one last job out of the way, a fiddle overdub on “Soul of Man.” In the earlier recording session the best vocal track and the best fiddle track had the misfortune to be on different tapes, so Banana balanced Ed Neff’s mike with the level of the tape, and the phantom fiddler, Snead Hearn, skulked in for a repair job.

Snead, a name Ed cribbed from an old W. C. Fields movie, can also be heard as second fiddle on “Virginia Waltz” on the “Dreams” album, through the magic of Banana’s engineering talents.

By the time Ed’s overdub is done, the rest of the band is gathered in the control room for a last listen at the tape. The mood is jocular: Bruce: Well Butch, what do you think?

Butch: I think we ought to go into the aluminum siding business ….

The mood is also enthusiastic, for the tapes are beautifully played and superbly recorded.