Home > Articles > The Archives > Hazel Dickens—Only A Woman

Hazel Dickens—Only A Woman

Hazel Dickens—Only A Woman

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1982, Volume 16, Number 8

Author’s Note:

I had been a fan of Hazel Dickens, her singing, her songs, and her seeming politics for a decade before I actually met her in late 1978 when she came to a concert by my band (true-to-form supporting a tradition-oriented band). Early in 1979 she and I were, among others, on the NCTA mountain music tour, and we became fast friends. Since then, members of my band, most frequently John Baker and I, have played and sung with her on several appearances, and helped her on her latest LP. She returned the favor by appearing on our new album. The information for this article has been gleaned not only from that association but also from articles and extensive interview tapes which Hazel provided. But the motivation was planted years ago when I first asked a BU staff person about Hazel, and she answered “She’s only a woman.” Well I suppose that’s so. After all a diamond is only a rock.

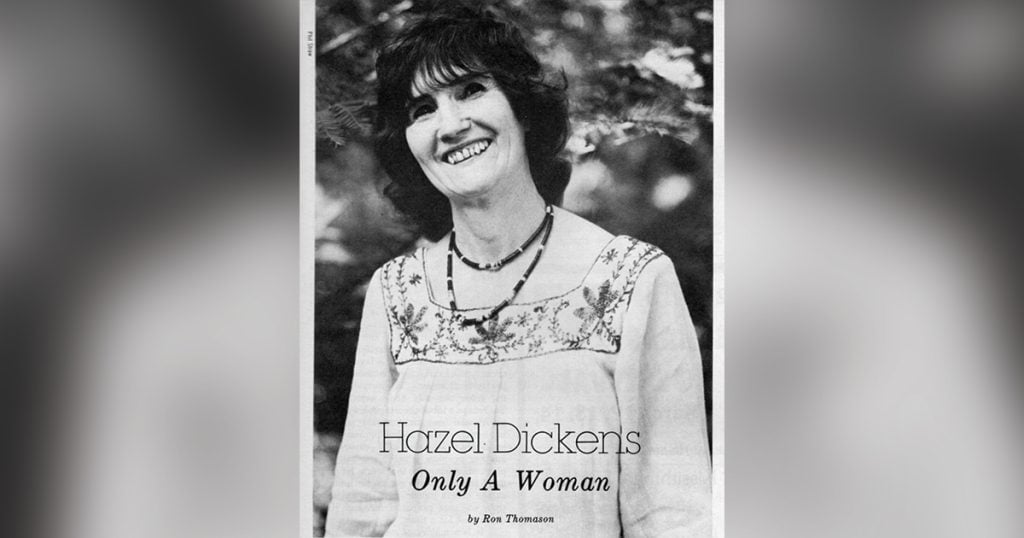

She sings. It’s a crystal voice attacking scarce melodies, flirting with dissonance on the harmony line —it cuts on the edge. She writes. Her songs of life are subtle metaphors and plots with obvious symbols. Her songs of love are elegant but unshorn, often with sentiments of vestigal mountain culture in which things of the land are loved as people. Her songs of protest rip your skin off. She is Hazel Dickens.

Few have taken bluegrass music to such a wide and varied audience. She has played the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Lincoln Center, Madison Square Garden, and Kennedy Center. In balance she has toured deprived areas and carried the music to grass roots folks. Her performances are sought after by women’s organizations, miners’ advocates, hard core bluegrass fans, and the intellectual-ferment crowd. She wrote and per formed songs for the award-winning documentary film Harlan County, U.S.A. and was specifically requested to write the song “Rebel Girl” for the movie With Babies and Banners. She has received international acceptance for her hard-wrung mountain voice, performing and touring in Europe and Latin America. Personal sketches of her music, politics, and way of life have appeared in such newspapers as The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and Washington Post; as well as the books Watermelon Wine and Voices From the Mountains. Best of all she has done this without commercializing her singing; rather she has maintained a raw spontaneity to her vocal presentations while selecting obscure traditional songs and writing in a straight-ahead, fundamental vein.

Though her childhood was not unique, it was rigorous. She was born in Mercer County, West Virginia, but the family moved often, always settling in small mountain communities and coal towns for short periods. Hazel’s father was a Baptist preacher with a powerful singing voice who played overhand banjo. Her mother was the mythical mountain matriarch who bore eleven children at home—feeding, clothing, teaching, and enduring. Together they raised their family with the ominous power of “go cut your own switch” tempered with a healthy dose of mountain generosity. Hazel remembers, “We lived by some railroad tracks and sometimes the bums would get off the train and knock on the door. My father would always try to give them something, even though we often didn’t have much ourselves.”

One of the few recreations available to large, poor families in Appalachia was singing, and the Dickens’ household was typical. Hazel’s brothers learned to play and sing, and her mother would frequently sing while doing chores. But her father was especially proud of Hazel’s singing; and while she was still very young, he would call on her to perform for company by singing his favorite, “Man of Constant Sorrow.” Hazel’s first audience was burned into her memory by her painful shyness. A classmate had told the third grade teacher that Hazel could sing; and so she was called upon to do so, delivering Ernest Tubb’s “I’d Die Before I’d Cry Over You” to the supportive class but less than enthusiastic teacher.

Her father’s involvement with the church and the way in which he sometimes gave it a higher priority than the family itself, contributed to Hazel’s rather cynical view of religion. She sees religion as being just one more force which is used to subtly exploit mountain folk. “These people would take the blame for every bad thing that happened. They would work and work and maybe, through their own efforts, have one little nice thing happen. Then they wouldn’t take any credit for themselves—they’d give it all to the Lord. I can’t buy that. People who work that hard deserve a lot of credit.”

Hazel herself had a difficult rite of passage. She saw the new cars and pretty clothes of visiting, former neighbors who had migrated to the cities and was determined to follow her brothers and sister to Baltimore. Here she was forced to acclimatize, as all country folk were, to a culture for which she was not prepared—uninitiated. She met the challenge of the new life: supporting herself by working in factories and shops; determined to preserve her integrity and independence. Here too was the incubator which turned her into an artist, for it was in Baltimore that she first encountered people who hungrily wanted to learn about her singing, the songs, and her background and culture.

If she were not a woman. Hazel’s induction into professional music would not be unlike that of so many others which the Baltimore-Washington nursery has given to bluegrass. The first band she played jobs with started at a party jam and included her brothers, Arnold and Robert, and Mike Seeger. “Competition for jobs was really fierce. I think they gave me a guitar, even though I only knew a couple of chords, because they didn’t want the bar owner to think he was getting cheated” (by paying for someone who could sing but not play). Soon Bobby Baker joined the group after Arnold quit. “I got forced into doing the talking because no one else would.” Hazel, who has always wrestled with shyness on stage, remembers vividly that and the fact that “I sang what women were supposed to sing (Kitty Wells’ songs) at the time.” Soon followed a myriad of groups in what Hazel calls her freelancing period of playing bass and singing tenor. The first was Bobby Baker and the Pike County Boys which also included Bob Shanklin, Dickie Rittler, and again, Mike Seeger. Then a stint with Jack Cooke’s band. And there were others: “Not many people had a bass. Since I was making good money at a factory, I could afford one.”

These experiences were difficult for a woman, and Hazel first encountered the exploitive situations and began to form the indignant reactions which would one day make her a favorite, and archetype of sorts, for feminists. “It was pretty disillusioning. The men were playing roles the way they were taught. There was a lot of cheating (on wives and girlfriends) and they would probably have rather had a looser person (in the band than I).” She also experienced another problem which historically has plagued women in the work force: “I don’t think I always got as much money as the others (musicians).” It was more than she was prepared for, and Hazel quit music for a time.

It is a matter of record that Hazel not only took music back up but has developed into a songwriter and singer with good instincts and polished techniques. Time is a great editor; it eliminates the inessentials, focuses on the main forces. Hazel now recalls the forces that influenced her came from friends who supported her music, sought out her knowledge of lyrics and tunes, and believed in her abilities to write and perform.

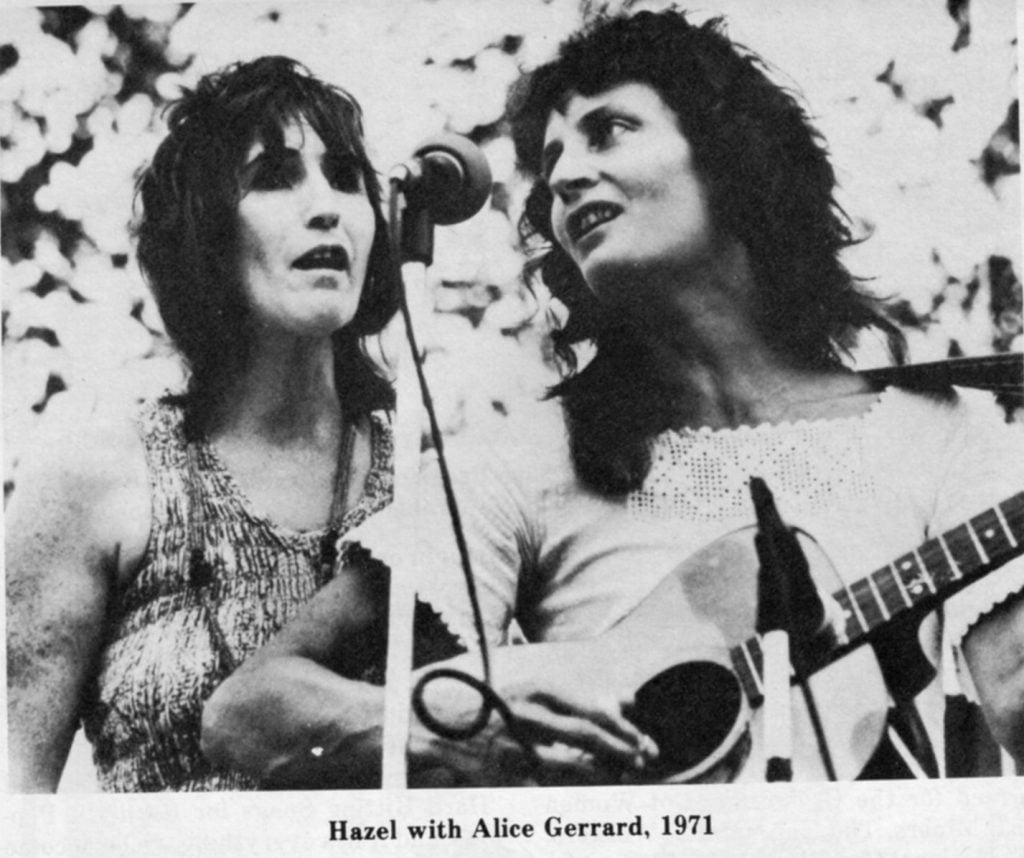

And so came the records. Between 1965 and 1976 the duet of Hazel and Alice Gerrard recorded four LP’s, two for Folkways and two for Rounder; and they were an integral part of the LP recorded for Arhoolie by the Strange Creek Singers. (During this time Hazel herself guested on other records and appeared solo on four cuts of the LP, “Come All You Coal Miners.”) Hazel and Alice had a tremendous impact on bluegrass music. Their first two LP’s were strictly bluegrass, recorded with full bands. At that time their approach to singing was aggressively traditional, consisting of accurate melody and Spartan tenor that served to underscore bluegrass’s in herent, beautiful structure. The duet’s choice of material always favored the obscure, and thus they enriched the general bluegrass repertoire with their recordings of such songs as “Who’s That Knocking?,” “Darling Nellie Across the Sea,” and “Lover’s Return.” But they also added much of their own to the music by writing in the traditional vein songs like “Cowboy Jim” and by digging up antiques like “Train on the Island” and “A Distant Land to Roam.”

By the time the two good friends recorded their third LP, they had begun to leave the strict confines of bluegrass though not the strictures of their own beliefs in the traditional. There was still the driving “Tomorrow I’ll Be Gone,” but the power of the album was founded on the stark and flaying harmonies of songs like “Green Rolling Hills of West Virginia” and “Hello Stranger” (both recorded by Emmylou Harris) and mature compositions like “My Better Years,” “Fly Away, Little Pretty Bird,” and, of course, “Don’t Put Her Down, You Helped Put Her There” (used by New Riders of the Purple Sage).

The fourth and final LP by Hazel and Alice represents the duet at its most fully developed and complex stages and was recorded a short time before they decided to go their separate ways. There was only one bluegrass number, “Montana Cowboy,” —true to form; it was obscure. The songs on this LP were more diverse and the lyrical content was not as unified as before, but the harmonies were more intricate. Hazel’s songs on the album, “Rambling Woman,” “Working Girl Blues,” and the awesome “West Virginia, My Home,” provided a glimpse of the sophistication and artistry that was becoming hers.

But it is not practicable to consider Hazel’s music, songs, and performances today without first considering a more important aspect of her character. She is a “political” person, and I use the epithet advisedly because Hazel herself uses it to bestow the highest compliment. To her, political people have identifiable characteristics; even though one of these is that they are highly individualistic and they represent every aspect of the social and economic strata of society. She believes them conscientious, informed, charitable, compassionate, dedicated, and active. Hazel is all of these, and it has provided her with some of her greatest personal rewards in the form of self-gratification; especially when her singing benefits working-class people. She has, of course, certain causes with which she closely identifies, and they are the problems and concerns of the following groups: miners, women, abused children, the aged, and culturally-alienated Appalachian folk. However, she does not confine her efforts to working for just these groups, but rather she tries to do what she can for whomever needs help. She is a humanist.

It is of passing interest that she sees bluegrass music as political. There have always been bluegrass songs with a political bent; “True Life Blues,” “Dream of a Miner’s Child,” and “Two Soldiers” to name a few. But this fact alone would hardly make bluegrass political: and Hazel’s view is based on a more philosophical position. She sees the traditional-style performances; the integrity of choosing quality in music over commercialization; and the struggle to preserve, through music, traditional country values and concepts as being a political stand. She has, through the years, supported traditional performers, (“For going to see the Stanley Brothers or somebody like that, we didn’t care about the expense or how far we had to travel.”), and she has always maintained the traditional integrity of her own performances. “I strive for honesty and truth…so the audience can believe…me.” In a similar way Hazel has become introspective about her writing—caring that it may represent the feelings or situations of others. “Sometimes I just get this real lonesome feeling inside, and it (a song) just starts out as a moan or a groan.” She believes that there is need for a concentrated effort to write good bluegrass songs and that staying within the prescribed structure is important. Hazel further appreciates the value of editing in songwriting but says, “Utimately you have to be the one to make the final decision…it’s your song.” Hazel performs with bluegrass and old-time backing these days. She likes to present her vocals with sparse and tasteful music. She relishes harmony and prefers to use musicians who also sing. “I long for a gutsy lead singer to work with…A lot of women don’t sing hard enough…it’s because of their conditioning.”

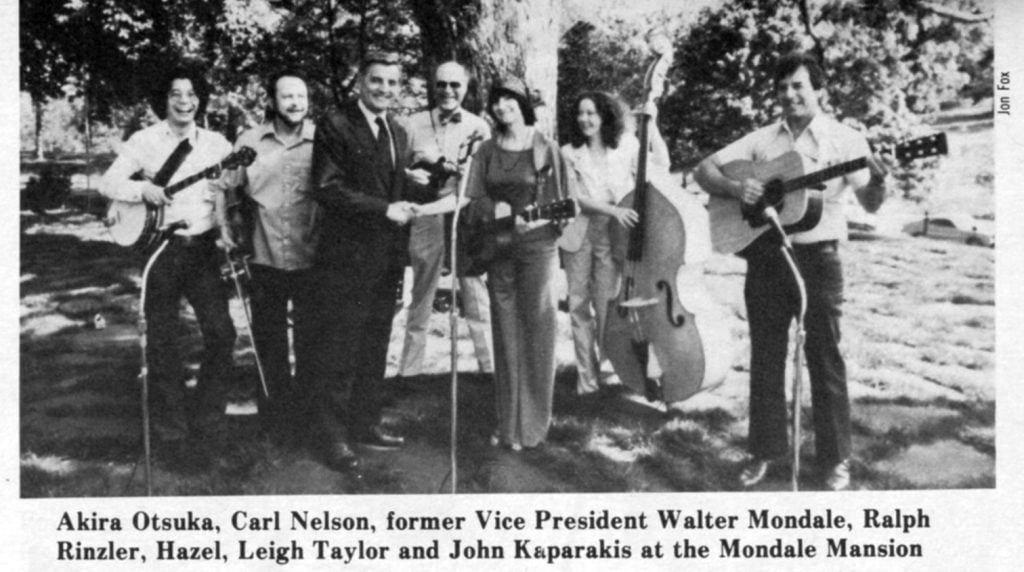

Her work frequently showcases her activism, and she often plays for audiences with definite political sympathies. In the past year she has performed for the Organization of Women Coal Miners, The United Mine Workers, the National Organization for Women, at folk and bluegrass festivals like John Henry and Wheatlands, for numerous college audiences, and toured with the Southern Grassroots Music Tour (She’s also a board member) and the National Council for Traditional Arts’ “Mountain Music Homecoming” troupe. Her concerts always offer a variety of material and approaches. She still does old songs with traditional harmonies, favoring the unattended with choices like “You’ve Been a Friend to Me” and “Hide You In the Blood.” She consistently presents new, well-conceived originals which deal with contemporary themes and practical problems faced by common people. Still the splendid part of every show is when she piques the conscience with the tragic “Old Miner’s Grave” or the venemous power of an a capella “Steels of a White Man.”

She plays guitar in the Maybelle Carter syle and bass. When the situation demands it; she performs solo, accompanying herself appropriately on guitar. She has an untarnished ear for melody and can teach intricate tunes to lead musicians from memory. Moreover, she is critical almost to the point of destructiveness of her own writing. Though she feels every writer’s frustration, “I know what I want to say, but I don’t know the right words,” actually she has an intuitive grasp of metaphor and a true gift for using coarse and scathing imagery.

Fronting her own band has enabled Hazel to do things that provide her with new horizons. She is able to explore her potential as both lead singer and tenor and has that rare capacity to switch the parts comfortably found only in an Ira Louvin or Bill Monroe. She projects feeling: “I am an emotional singer…maybe I’m a masochist.” And she likes to improvise. Her interests are keener than ever in music now: “I never get quite satisfied (in concert)…(I don’t) try to project something that isn’t real.”

Her latest LP is a solo effort called “Hard Hitting Songs for Hard Hit People,” and it has everything we have come to expect from her. She has always recorded with respected musicians; such as Chubby Wise, David Grisman, and Lamar Grier. Her latest is no exception, and the likes of Hargus “Pig” Robbins, Norman and Nancy Blake, Buddy Spicher, and James Bryan appear. The arrangements run from glittering Nashville to lonesome country. Her selection of material was particularly acute: There is a cajun-style “Busted;” a Carter-like “Lonesome Pine Special;” poignant originals in “Old Calloused Hands” and “Lost Patterns;” the two- fisted political songs, “They’ll Never Keep Us Down” and “Aragon Mill;” and a lilting new arrangement of “West Virginia, My Home.”

Hazel played the White House on Labor Day of 1980, which was indicative of her stature as a spokeswoman for working people. She has recently received national attention for her songs and singing in Harlan County, U.S.A. for which she expressly wrote the closing song; and she also wrote and performed for With Babies and Banners, by request. Such attention, though well-deserved and undeniably growing, belies her very private, even secluded, lifestyle. She is a lady who expresses her sensibilities through writing poetry that she is reluctant to share and who manifests her countryness by serving up home-cooked meals for company. She reflects accurately on her own hard life and strives by this means to empathize with the struggles of others. Her writing craftsmanship is at its peak, and bluegrass fans will soon have gems like “Lonely People” and “Mt. Zion’s Lofty Heights.” Watch for them. Better yet, watch for Hazel.

Share this article

4 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Thank you SO much for publishing the 1982 article on Hazel Dickens! Ron did a superb job and is such an excellent writer/storyteller! Hazel was an amazing person and an inspiration for so many people who still miss her dearly!

For your readers who may not know Hazel, here are some updates to the article such as:

– 2017 Inducted into IBMA’s Hall of Fame (“Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard”)

– Recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship, the highest honor the US gives for folk and traditional arts. She was inducted the same year as Bill Monroe.

– Recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Folk Alliance (the same year it was given to Bill Monroe)

– Inducted into the Society for the Preservation of Bluegrass Music’s Hall of the Greats

– Inducted by Alison Krauss into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame

– In 2010 the Mayor of San Francisco recognized her on stage at the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival and named that day San Francisco’s Hazel Dickens Day.

– She had a book written about her

– A film documentary was done on her

Needless to say, many people were very disappointed that she was inducted into the IBMA Hall of Fame as a duo with Alice Gerrard … nothing against Alice, per se. It’s just that Hazel had so many more accomplishments and achievements (albums, songs in movies, activism, accolades, etc.) on her own as an individual that deserved recognition that it would have been great to recognize her for that! Interestingly, the NEA, SPGMA, Folk Alliance and West Virginia awards were all solely recognizing Hazel and were given to her long before IBMA inducted her into its Hall of Fame.

Hazel was my aunt,Her brother Thurman Dickens was my Grandpa.I never knew them but it’s an honor to be able to learn about her life style and the way things were back then.I wish that I could of met them before there passing .

Thurmon was my grandpa too.. My mom was Hattie Arlene Dickens Craddock. May I ask who your parents were please. ?

I was lucky enough to meet Hazel, attend a concert and enjoy a family reunion. There was a lot of music at the reunion to enjoy. I never got to meet Thurman.