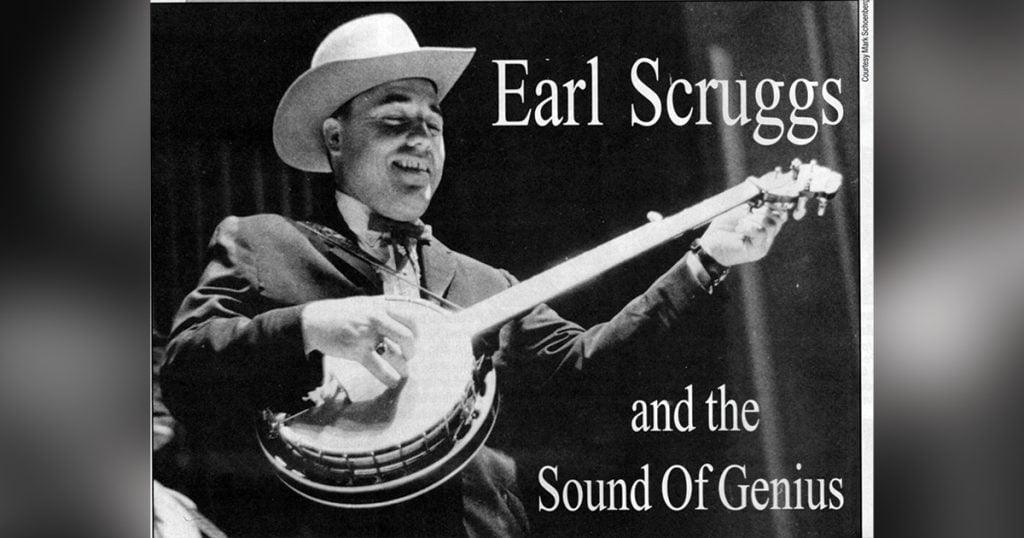

Home > Articles > The Archives > Earl Scruggs and the Sound of Genius

Earl Scruggs and the Sound of Genius

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 2012, Volume 46, Number 12

We knew Earl Scruggs couldn’t live forever, even though we hoped he would. When the end inevitably came, we all felt a shift in our center of gravity, a hole in our hearts where Earl and his music have always dwelled. We remember where we were and what we were doing, and our feelings of loss when the World Trade Center was bombed, when the Columbia space shuttle exploded, and when Bill Monroe died. And now Earl Scruggs.

On the evening of Wednesday, March 28, I was answering e-mails when a couple of new ones appeared with brief, terse announcements from senders who had just learned themselves and were still coming to terms with the news. While it was sinking in, a few more arrived and I too had to think about life without Earl Scruggs, giant among giants, the pied piper whose music seduced everyone who responded to it, and the modest, cordial man who understood the impact he made without being impressed by his own greatness. Life without Earl Scruggs—the idea takes some getting used to.

North Carolina

His life began on January 6, 1924, in Flint Hill, near Shelby, forty miles west of Charlotte, into a musical family. “My father played old-style banjo so I had a banjo there, and my brother Horace had a guitar, and so we started playing just old tunes that we’d heard before. A little later, we got a Sears, Roebuck, & Co., radio and started listening to the Grand Ole Opry and programs like that.” Earl enjoyed telling how he figured out how to play “Reuben” while daydreaming when he was ten years old, experimentally alternating his thumb and two fingers, when it occurred to him that he was onto something. “I was in what we called the front room with a banjo one day…and when I realized what I was doing…it was like having a dream and waking up…that was the mode I was in and what I learned is exactly what I’m doing today.” His version from 1960 is very close to Wade Mainer’s “Old Ruben” (1941). Both are played in D, with unfretted open-tuned strings emphasizing the notes of the ancient melody, and both suggest that North Carolina old-timers probably played it in much the same way. Even if Earl began the banjo revolution when he picked “Reuben” with a middle finger added to his alternating index finger and thumb, he did so while maintaining its traditional feel and flow. The technique still worked when Earl tried it in G, and it gave everything he played a new and different sound.

Other banjo players Earl remembered from his youth included Rex Brooks, Leaborn A. Rogers, Mack Crow, Smith Hammett, Snuffy Jenkins, Earl’s older brother Junie and a neighbor, “Mack Woolbright [ca. 1891-1960], playing on the front porch of our Uncle Sidney Ruppe’s home. As he rocked in a porch chair, he picked out ‘Home. Sweet Home’ in the key of C. The G chord he played in this number was one of the most thrilling sounds I had ever heard. I was about six years old [1930] at the time and marveled that a blind person could play so skillfully.” Woolbright’s 1927 version, with his partner Charlie Parker, was part of a parody, “The Man Who Wrote Home Sweet Home Never Was A Married Man.” Earl’s “Home Sweet Home” from 1960 is a close match, and offers a glimpse of banjo music in his community prior to his birth.

In a 2003 radio interview with Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air he stated, “The only thing different from my playing and what I’d heard is that I had a three-finger roll that has later been called Scruggs style. It seemed to help me to play slow tunes as well as up-tempo tunes.” Offering a slight self-correction, he added, “It’s a little misleading to say three fingers. It’s actually two fingers, middle and index finger, and your thumb…if you number your thumb one, the index two and your middle finger three, it’s like a one-two-three roll, over and over.”

He mastered the style well enough by 1939 to join the Morris Brothers at WSPA in Spartanburg, S.C., when he was just 15. During the war he worked in a local thread mill, often putting in 72-hour weeks to meet defense quota requirements. Earl returned to music when he joined Lost John Miller’s band in Knoxville, whose schedule included weekly trips to Nashville for 15-minute Saturday morning shows on WSM. By year’s end, Miller was no longer touring and Earl Scruggs was a featured and increasingly celebrated member of the Blue Grass Boys.

The Blue Grass Boys

Earl and his music came of age in the 1940s, and was part of the profound change American music was undergoing across the board. Distinguished composers like Bela Bartok, Paul Hindemith and Igor Stravinsky had fled Europe in the 1930s and were reinvigorating concert music in America, while Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk were blazing new paths on the jazz map with the angular, unpredictable sounds of bebop. Postwar country music figures like Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb and the Maddox Brothers and Rose stressed new honky-tonk themes that included day labor, bar rooms and alcohol, dysfunctional love and other woes that reflected the experiences of country people leaving the farm and coming to terms with industrial work and urban behavior. Amplified steel guitars and take-off solo guitars became essential to the updated country sound.

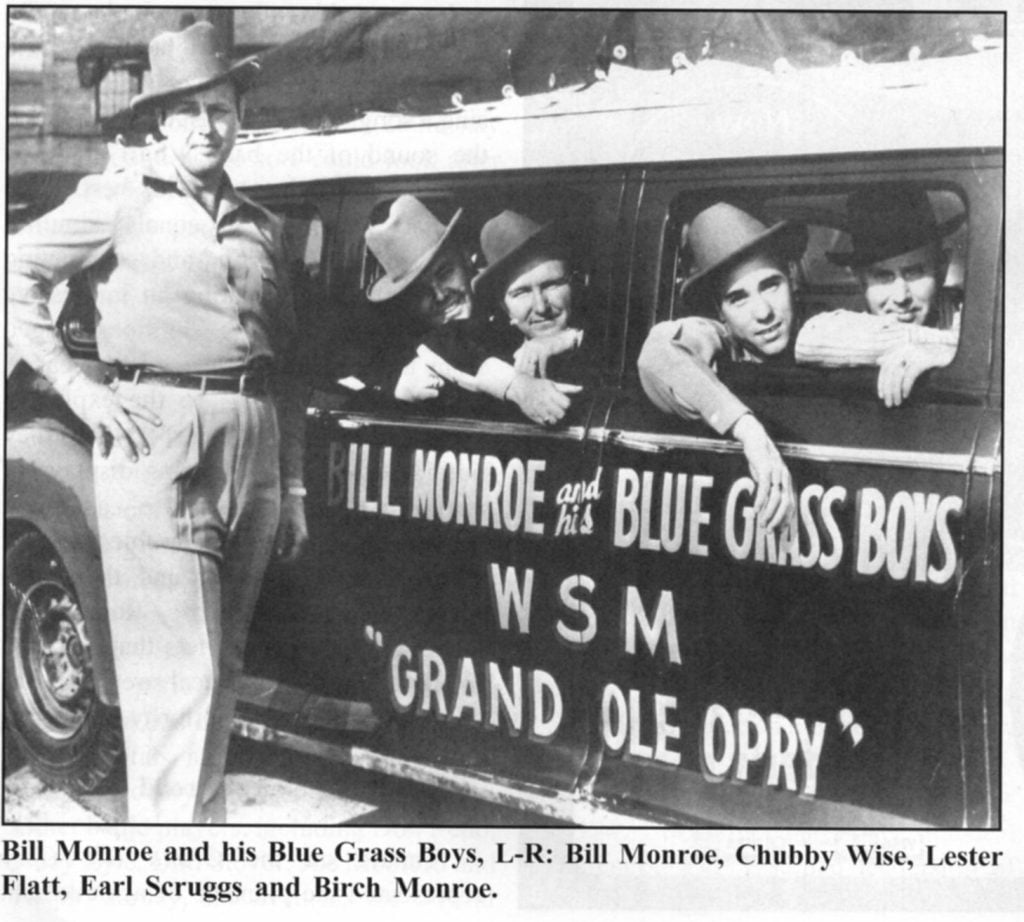

Bill Monroe began his own style of music when he founded the Blue Grass Boys in 1939. His songs stressed the traditional values of farm, family and church, and his high-pitched rear-back-and-holler singing complemented the updated sounds of the fiddle and mandolin, pushing the envelope with his dazzling skill and reinforcing them with hot string bass rhythms that propelled the band from below and hinted a little at jazz. By 1945 the Blue Grass Boys were a tight, skilled ensemble, successfully creating popular new music out of old ingredients. His new songs had a familiar feel that fit the Monroe style, with old-time vocal harmonies that reinforced Bill’s and Lester Flatt’s lead singing. The band combined tradition with innovation, creating exciting original music that made everyone sit up and take notice.

And all that was before the arrival of Earl Scruggs who joined in December 1945, following an audition with Bill that fiddler Jim Shumate went to some pains to arrange. Lester Flatt, already in the band, enthusiastically seconded Shumate’s choice and Earl was promptly invited on board. His acceptance streamlined the development of Bill’s music and determined the direction of the rest of his life. His banjo completed the ingredients list for the formula that would later be called bluegrass, adding the vital component to Bill Monroe’s music that created its critical mass and hallowed stature. Eddie Adcock recalls trying to hear the Opry on the radio from central Virginia in those days: “If it was after one of Bill’s songs, you couldn’t find the station for a while because the applause was so loud, it just sounded like static.”

Bill’s mandolin playing shared the high range emphasis of the fiddle, whose best exponents, including Tommy Magness, Art Wooten, Howdy Forrester and Chubby Wise, had all played in the band by 1945. In Bill’s four-piece ensemble, the non-soloing bass and rhythm guitar filled out the middle and bottom, emphasizing the first and third beats of each measure while Bill’s mandolin chop provided the off-beats. For more variety he added Dave (Stringbean) Akeman, whose banjo filled the middle spaces but didn’t keep pace rhythmically after Lester Flatt joined the band to play rhythm guitar in March 1945. Earl’s playing was more versatile and flexible, complementing Bill and Lester with ornamental backups, hot solos, interior harmonies and flawless timing. As Eddie Adcock further remembers, “I saw Bill Monroe at the Victory Theater in my hometown of Scottsville, Virginia about early 1945 and then again when he came with Lester and Earl in his band in ’46 and probably ’47, and it was a whole different, stepped-up sound that just seemed totally unique, and Earl was really what made the difference.”

Earl’s arrival severed any remaining ties the Blue Grass Boys had to hoedown style, western swing or honky-tonk. His banjo, humblest of traditional folk instruments, became a revolutionary focal point of the new music that would eventually be dubbed bluegrass. The music now had a hard, emotional edge, with love songs inspired more by disappointment than fulfillment, and instrumental techniques that required exceptional musicianship. Earl was at the core of that development and his music caught on immediately, especially after Opry host George D. Hay dubbed him “Earl Scruggs and his fancy banjo.” Earl was flattered and astonished. “That was a miracle to me,” he said. “Judge Hay believed in a bunch of old-time stuff…and. as luck would have it, he went along with what I was doing.”

In Earl’s gifted hands, a five-string banjo could match anything Bill played on the mandolin, and Bill’s music evolved to match the challenge. As Earl put it, “He just did the type of tunes that made the banjo sound good…He had a solid beat that could support anything you wanted to pick…if a man would slack off, he would move over and get that mandolin close up on him and get him back up there. He would shove you and you would shove him and you would really get on it…he would spend a lot of time just tightening up the group. Some rehearsals we wouldn’t even sing a song; we would just concentrate on the sound of the band.” Earl and Bill inspired each other to do his best. They became well-matched equals, simultaneously collaborating and competing with each other, creating an impressive body of music whose emotions ranged from the gentle, tear-stained “I Hear A Sweet Voice Calling” to the explosive “Why Did You Wander,” when they outdid each other in blazing displays of virtuosity. Earl was also a quiet, dependable harmony singer, blending his voice with Bill, Lester and their bass player Howard (“Cedric Rainwater”) Watts in trios and quartets that matched the Blue Grass Boys’ vocal strengths with their instrumental superiority.

Life on the Road

Tenure on the Grand Ole Opry represented the pinnacle of achievement for country music talent in those days, but in order to exploit the publicity it engendered, the talent had to hit the road and go where the audiences were. WSM’s 50,000-watt clear channel signal could be heard far and wide, and that’s where the audiences were and to reach them, you had to travel. What was that like? “It was terrible!” Earl said unambiguously. “If I hadn’t been 21 years old, full of energy and just off the farm and [cotton] mill…I thought to do an hour show on the road was a pushover compared to eight hours in the mill or sun-up to sundown on the farm [but] we did it 24 hours a day, practically. Back then we had two lane highways and we traveled in a ’41 Chevrolet car. We’d leave after the Opry on Saturday night and maybe work down in South Georgia, about as far as you could get for a Sunday afternoon show, and on down to Miami or someplace on Monday or Tuesday. We’d work till about Thursday and start working our way back to Nashville. You’d be there just long enough to play the Opry, get a change of clothes, pack a suitcase and head out again.”

By the end of 1947 the road had taken its toll on several Blue Grass Boys, who handed in their notice on separate occasions. After departing, Earl and Lester Flatt were ready to return to their old day jobs, and Earl was concerned about the health of his mother when he wasn’t around. But then, “When I got home Lester called and said, ‘I don’t think we’d be happy going back into the mills, let’s think about it.’ He said we could stay close around home so I could look after my mother.” When Howard Watts learned they were starting a band, he gave notice to Bill and joined them.

Foggy Mountain Boys and Earl Scruggs Revue

Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys began as a southeastern regional group in 1948, expanding their reach through the 1950s with records, radio and television as a popular bluegrass/country outfit. Many songs they recorded, especially in the 1948-’53 period, remain core bluegrass classics to this day. Not surprisingly, the instrumentals attracted particular attention, especially among other musicians. Other banjo players, including Don Reno, Rudy Lyle, Don Stover, Joe Medford and Ralph Stanley, and even his old mentor Snuffy Jenkins, adopted elements of Earl’s style, and learned from his new banjo tunes.

Bill’s earlier instrumentals like “Honky Tonk Swing” and “Blue Grass Special” were more blues-based dance music than structured compositions. Their “Blue Grass Breakdown” and Earl’s subsequent “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” began a move toward music based on thematic development and instrumental virtuosity. Bill’s first Decca record in 1950 was “Blue Grass Ramble,” a multi-thematic tune featuring his nimble cross- tuned mandolin. Its first theme inspired “Earl’s Breakdown” in 1951 and Earl embellished it with a novel chorus featuring his tuning pegs. “Flint Hill Special” from November 1952 introduced customized tuners that allowed more accurate de-and re-tuning. It was one of Earl’s best, an intense performance featuring extend variations on an old tune remembered from childhood. “Dear Old Dixie” from the same date can be traced back to “Traveling Man,” whose melody also inspired Arthur Smith’s “Crazy Blues” in the 1930s. Earl’s new banjo tunes were a revelation, and his reputation as a brilliant soloist attracted increasing numbers of fans throughout the Foggy Mountain Boys years.

In the 1960s they helped Flatt and Scruggs extended their appeal to northern folk music revival audiences with festival and college campus performances, and became widely known.

Later record dates were augmented by Nashville session musicians, losing some old fans of the band and gaining it some new ones. In 1967 their Columbia Records producers Don Law and Frank Jones were replaced by Bob Johnston, who encouraged a rock-influenced hybrid style, covers of Bob Dylan songs and other folk rock material, and they obligingly altered their music to match the tastes of their new cosmopolitan audiences. The core of the band in the late ’60s still included Buck Graves (resonator guitar), Jake Tullock (bass) and Paul Warren (fiddle), all Foggy Mountain mainstays since the mid-1950s. For better or worse they all hung on, doing their best to meet challenges of the new music.

Inevitably Lester and Earl parted ways in 1969, in large part over musical differences. Earl assumed leadership of the Earl Scruggs Revue, which introduced Earl and Louise’s three sons and wove rock music around the sound of the banjo. Earl treasured the experience: “Randy, Gary and Steve were good musicians. One of the biggest thrills a person will ever get is to go on stage with his children, especially if they’re good musicians. Even though they are my boys I thought they were some of the best musicians I ever played with. They knew new material but they still sounded like the Scruggs boys when they played it.”

Earl and the Revue performed until 1980. Eddie Stubbs elaborates on their achievements: “Combining the elements of bluegrass, country, folk, rock, blues, jazz, and gospel, centered on Earl’s banjo, they took a unique brand of acoustic and electrified music to audiences that were not acquainted with the banjo, performing at folk and rock festivals, major night clubs, colleges, and stadiums.”

Afterwards the boys pursued separate goals and Earl went into semi-retirement, working when he wanted to and enjoying his new-found leisure. He continued to love the new music as much as the old. Over the years he made appearances and records with others, starting with Ray Price and Hylo Brown in the 1950s to latter day performances with Ricky Skaggs and Doc Watson (as the “Three Pickers”), Little Roy and Lizzy, Rodney Dillard, Johnny Warren, Tom T. Hall, Benny Martin. Lonesome Standard Time, the Chieftans and IIIrd Tyme Out, among others. At the memorial service in Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium on April 1, 2012, Eddie Stubbs remarked, “In his car, Earl’s radio dial was welded to 650-AM, WSM. He had CDs of the latest things Randy and Gary were working on along with others by the Carter Family and Uncle Dave Macon.”

Earl’s Banjo and Guitar

Earl’s most precious possession was his banjo. He probably recorded with his iconic 1930s Gibson Granada Mastertone banjo first on the 1949 date that produced “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” for Mercury Records. As he recalled, “While we were at WCYB [in Bristol, Virginia], Bill Monroe was in the area and we invited him to make an appearance on our radio program to promote his nearby show dates. Don Reno was with him at the time and approached me on the idea of trading his…banjo for my Gibson RB-3 [actually RB-75], and so the swap was made.” It was affectionately called “Nellie,” and Earl had played it on records with Bill Monroe in 1947 and on the first one or two Foggy Mountain Boys record dates in 1948-’49. Jim Mills notes that Earl played an RB-11 on the 1946 Monroe records.

North Carolina performer, bandleader, promoter and radio host Fisher Hendley bought the Granada (serial #9584-3) when it was new, and one of the few Gibson banjos made in the early 1930s with five-string necks. Snuffy Jenkins acquired it a few years later and may have played it on a record date with J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers in 1937. Don Reno acquired it from Snuffy around 1940. While Don was serving in World War II, the banjo suffered damage in storage from rosin that had melted on it, and he tossed in a Martin guitar to even up the trade with Earl.

That banjo remained Earl’s instrument of choice for the rest of his life. As he told Fresh Air’s Terry Gross in 2003, “It produces the sound that my ear’s looking for. Maybe I’ve just gotten used to it, but I like the sound that I get out of that particular banjo…I feel at home with it when I take it out of the case and [I] know what it’s going to feel like when [I]…start to perform.” Earl also devised D-tuners to facilitate playing “Earl’s Breakdown,” “Flint Hill Special” and other specialties that included de-tuning and re-tuning strings as part of a tune.

The trademark sound of that banjo in Earl’s hands was featured in the rural comedy Beverly Hillbillies TV series from 1962 through 1971 (where the band could also occasionally be seen), in the 1967 movie Bonnie And Clyde, and on the triple-disc hit record set Will The Circle Be Unbroken, hosted by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, recorded in 1971 and charting in 1972. The year 1971 was also when the movie Deliverance featured a five-string banjo in a prominent role. These landmark appearances and the Foggy Mountain Boys’ own syndicated TV series spread Earl’s banjo sound beyond the South to the rest of the world, especially to Europe and the Orient, making Earl Scruggs a household name in millions of households and inspiring a number of their occupants to take up the instrument themselves. Throughout the 1960s Columbia Records regularly released new LP sets by Flatt and Scruggs, and the Earl Scruggs Revue in the 1970s.

The sound of Earl’s finger-picked guitar was as distinctive as his banjo. Though jointly inspired by Maybelle Carter and Merle Travis, there was no mistaking it for anyone but Earl. From the outset Flatt and Scruggs sought to distinguish their music from Monroe’s, even while retaining much of his style. A surviving air check (“A Little Talk With Jesus”) features Earl’s guitar with the Blue Grass Boys; it would soon become prominent on Foggy Mountain Boys gospel songs, providing the same choruses and turn-arounds as Monroe’s mandolin. When “Jimmie Brown, The Newsboy” was released in 1951, Earl’s guitar evoked memories of the original Carter Family and it became the first of many recorded songs with which Earl would honor them, often while playing guitar. Earl’s guitar music has never received the recognition it deserves, but the instrument was no less important to him than his banjo. Eddie Stubbs adds. “Earl owned and played several guitars in the first decade or so of the Foggy Mountain Boys. His principal guitar for the remainder of his career was a Martin D-18 that he acquired in the late 1950s from Don Gibson.”

Last Years and Louise

Earl’s final years were quiet ones, though he stayed musically active. He and Louise stayed in the Madison, Tenn., home they shared until they moved to nearby Oak Hill around 2000. Louise died in 2006, after their 57-year marriage. When the couple met in 1946, Earl was Bill Monroe’s treasurer. He kept the job and handled bookings during the Foggy Mountain Boys’ early years until Louise assumed those duties in 1955. She soon came into her own as a skilled promoter and successful business manager who determined much of the direction the band would take through 1969 and her family’s professional life thereafter.

His awards included several Grammys, a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment For The Arts (1989), National Medal Of Arts (1992), induction into the Country Music Hall Of Fame (1985) and the International Bluegrass Music Hall Of Fame (1991). In 2003 he received a star on the Hollywood Walk Of Fame. Earl Scruggs Family And Friends (2001) is the title of a CD made for MCA that followed occasional appearances beginning in 1998. They appeared as often as twenty times a year for several years and usually featured traditional music. A 1967 remake of “Foggy Mountain Breakdown’’ had won a Grammy award in 1969; a 2001 version with comedian Steve Martin playing second banjo won a second Grammy.

Earl’s health was not the best. He had a hip replaced following a 1955 auto accident (that also injured Louise), surgery on his wrist and ankle after a 1975 accident in his private plane. In 1996 both hips were replaced and he received six coronary artery bypass operations following a heart attack in the hospital’s recovery room. Movement wasn’t always easy and he was never out of pain. His niece Grace Constant (daughter of his sister Ruby) became a valued caregiver in the last couple of years, attending to necessities and keeping Earl’s spirits up, even as she continued to hold down a day job. Invitations to Earl’s birthday parties were sought after by his colleagues. Mac Wiseman recalled one in 2004, when Earl turned eighty. “I looked and looked,’’ he said, “but I couldn’t find an eightieth birthday card, so I sent him two forty-year cards instead. Earl said it really made him laugh.”

It was great to have worked with him. He played some good banjo. I’ll say one thing, when Lester Flatt would call a number out, Earl would take off with it. As soon as Lester said his last words, we were gone. It was just like clockwork. Earl set the time with his banjo, and he kept it there. He was a great entertainer, and it’s a big loss to bluegrass music. —Curly Seckler

I’m convinced that God himself [sent] the music straight through Earl. That’s why his music finds its way so deep inside your heart and soul. —Marty Stuart

Earl Scruggs [had] impeccable timing, taste and tone—I think he [had] tiny brains in each of his fingers. Had I not seen Earl Scruggs, I doubt very much if I’d be playing the banjo. —J.D. Crowe

The old argument about who was the first three-finger really doesn’t matter, because without Earl in the equation, no one would be worried about it. —John Hartford

Earl Scruggs is Bluegrass Banjo. He perfected the style, brought it to the forefront and had all of us banjo pickers listening and attempting his licks. His banjo playing is the gold standard from which we attempt to learn. He leaves a music legacy that goes beyond what words can describe. I suspect all banjo pickers will continue to listen, study, study, and enjoy Earl Scruggs’ music for the rest of time. I know I will. —Karen Batten Bug Tussle Ramblers Ft. Myers, Fla.

Some people take up the banjo, learn some of Earl’s tunes and then want to go to the next level, beyond Earl. Pilgrim, there is no beyond. —“The Flint Hill Flash”

He lived an unmitigated triumph of a life, enabling the creation of the great American music form now known as bluegrass and ennobling his instrument of choice, the banjo. —Peter Cooper The Tennesseean April 1, 2012

He was the last of the original architects of what became known as bluegrass music, and no one in American music has ever been so closely associated with defining a musical instrument’s role as Earl Scruggs. The impact of his music will continue for generations to come. —Eddie Stubbs Earl Scruggs Memorial Service Ryman Auditorium April 1, 2012

(I’m most grateful to Eddie for enlightening me on several key points, and Jim Mills, who cleared up several important aspects of banjo genealogy. Earl Scruggs quotes come from “The Artistry And Accomplishments Of Earl Scruggs.” a superior article by the late Marty Godbey in Bluegrass Unlimited (August 1996), the Terry Gross NPR interview cited above. Earl’s own book Earl Scruggs And The 5-String Banjo (2005), and various unattributed sources on the Internet.)

Dick Spottswood’s Banjo On The Mountain, Wade Mainer’s First Hundred Years was published by the University Press of Mississippi (2010).