Home > Articles > The Tradition > Earl Scruggs

Earl Scruggs

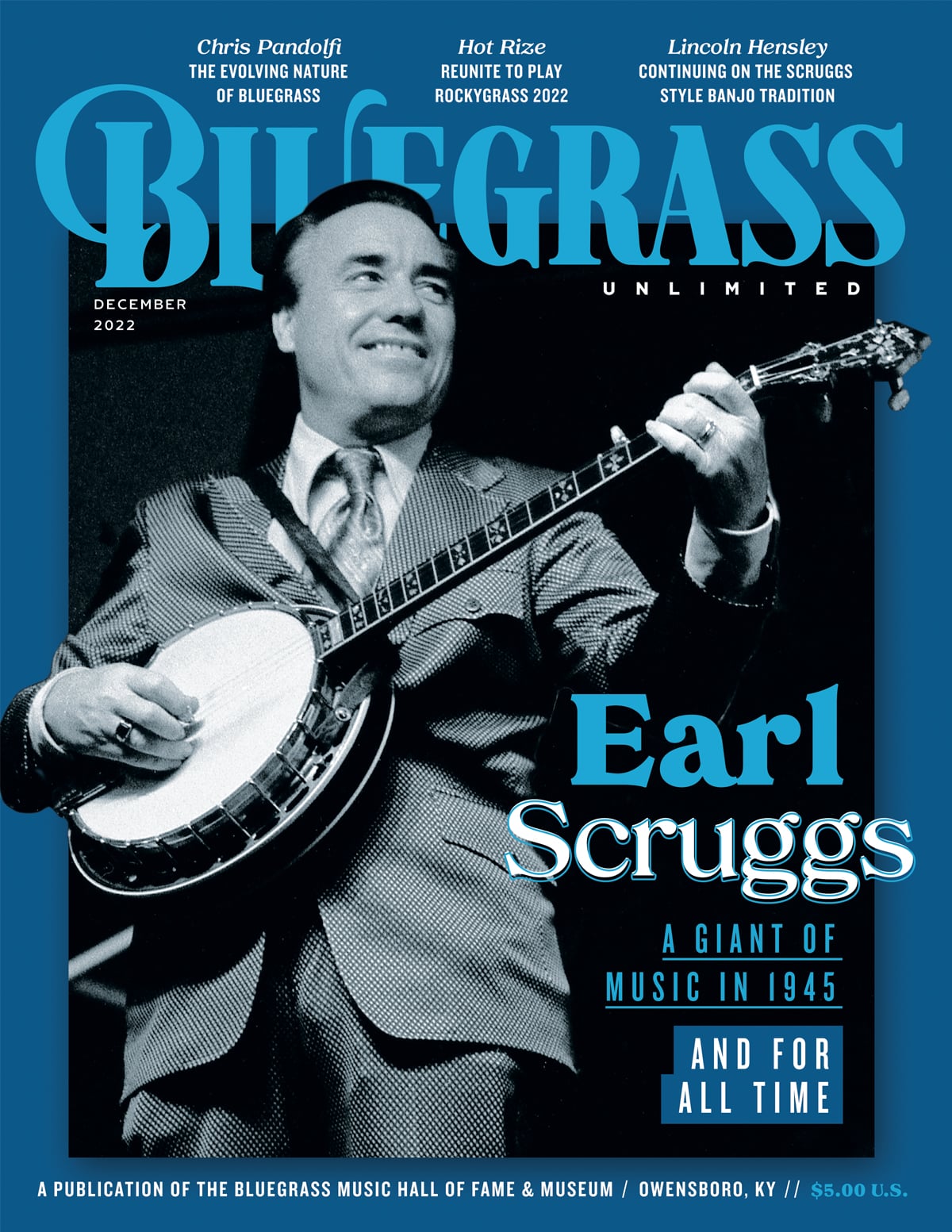

A giant of music, in 1945 and for all time

Earl Eugene Scruggs was born Jan. 6, 1924 in Flint Hill, North Carolina, in farm country in the Piedmont region. Early in his life there, he came up with a new, rolling, sometimes blazing-fast banjo style that has kept his name out front through the years, long past his death on March 20, 2012. From his native Cleveland County to the world, it’s known as Scruggs style, and the distinctive approach is key to bluegrass music, musicians and lifestyle.

As an internationally known folk-based musician, Scruggs has been the model for countless banjo players and his propulsive style beats at the heart of bluegrass music. Some of the best players and bands adopt his imaginative approach to music as well as his specific style. That’s meant that players have had to learn more than a rote set of licks that would always apply in a given place in a song.

“Every banjo player argued for my whole life about exactly how Earl Scruggs played this or that,” Béla Fleck, the most highly regarded banjo player of the current day, said during the first Earl Scruggs Music Festival, during Labor Day weekend 2022, in North Carolina.

“Meanwhile, Earl Scruggs played it however he wanted, every single time. He never played it like that again, except on that one record or in whatever places and we all argued and argued that it was this finger number. But I’ve watched him and he would use whatever finger he wanted.

“I finally got to go over to his house in his later years and finally got to watch him do it, and to see how fluid he was with his language.”

In addition to his definitive style, people remember Earl Scruggs for his kindness, his determination, his gentle humor, his willingness to mentor other musicians, or just to pick with them in informal settings. For the generations who saw him on the popular Beverly Hillbillies show and in other situations, he defied the pop-culture stereotypes of an ignorant backwoods Southerner. Earl Scruggs was smart, friendly, understated, humorous, and of course brilliantly talented.

The effects of his musical achievement remain a strong force, in this style of music and beyond. Generation after generation of banjo players have worked their tailpieces off to achieve some version of Scruggs’ speed, gorgeous sound and acute sensibility. Well into the 21st century, even factors of distance, language and lack of mentors can’t stop those who get the fever.

“It’s not easy learning banjo in Oslo,” said Norwegian musician Magnus Eriksrud before going on stage with Hayde Bluegrass Orchestra in Raleigh, North Carolina, in October 2022.

‘Banjo Is Really Important’

Like so many other acoustic ensembles since 1945, Hayde Bluegrass Orchestra found the instruments and singing styles of bluegrass worked well to express traditional and original country-themed tunes, leader and mandolinist Joakim Borgen said. Singer Rebekka Nilsson, who won an IBMA award as best emerging female vocalist, sang in a blend of bluegrass, folk and pop styles, but the band’s banjo, dobro, and fiddle playing showed their roots in Scruggs territory.

“Banjo is really important in keeping the pace of the music up,” Eriksrud said.

In another example of Scruggs’s continuing influence, this year saw the successful first edition of the festival in his honor near Tryon, North Carolina. The three-day event drew thousands of fans to see top-line artists such as Jerry Douglas and his Earls of Leicester, a tribune to Flatt and Scruggs; Béla Fleck and My Bluegrass Heart; Sam Bush; Molly Tuttle; Alison Brown; the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band; Acoustic Syndicate; and rising stars such as Darin and Brooke Aldridge.

“The festival took place with a monster group of musicians, all of whom were influenced by Scruggs and his three-finger banjo style,” journalist Rick Davidson wrote in MusicFestNews. “Held at the massive Tryon Equestrian Center with two outdoor stages just thirty minutes from Shelby, it was a great opportunity to celebrate this humble man and his influence on American music.”

Less than a month later came strong support for Scruggs’s creative approach in recognition of his devotee Fleck, who won four major International Bluegrass Music Association awards, for banjo player, album, instrumental group, and instrumental recording of the year. The music of My Bluegrass Heart used the traditional instruments of the style on some compositions that fans might have considered “out there.”

However, Fleck learned during his days of hanging out with Scruggs that the originator appreciated some risk-taking on the banjo. “I used to go over and jam with him,” Fleck said. “I tried to play just like him. I’d slip up every once in a while and he would laugh.

“I realized that was the point where he would really enjoy it and I started playing crazier and crazier. We had a number of jams of ‘Foggy Mountain Special’ where we were goofing around.”

In addition to Fleck’s IBMA wins, the top honor, entertainer of the year, went to recent phenom Billy Strings, who includes songs by Flatt and Scruggs, Bill Monroe and the Stanley Brothers along with jam-band style excursions in his sold-out shows.

Scruggs and Cleveland County History

Even beyond his influence on music, Scruggs has increasingly gained importance based on his journey from boyhood in Cleveland County to prominence in music, television, film and education. In just one example, the Earl Scruggs Center in Shelby, N.C., annually brings in more than 1,000 fourth-graders to learn about Scruggs, about the history of the county and about the chance to transform their lives through music and culture.

A key to this effort was signing up the Bluegrass Ambassadors, the nonprofit unit of the Chicago-based band the Henhouse Prowlers. At the 2022 IBMA convention in Raleigh, banjo player Ben Wright talked about researching and bringing to 9-and 10-year-olds varied pieces of their own Cleveland County culture and history to an increasingly diverse region once dominated by agriculture and textile mills.

“There’s a lot more to Earl Scruggs than the three-finger roll,” Wright said. “He worked at Lily Mills. And I was like, ‘Well, how many mills were around there?’ And it turned out there were hundreds of those.”

The fourth-graders who come to programs in downtown Shelby are from Cleveland County schools, where systemwide about two of five children are students of color. They learn about Earl Scruggs and his music, and see the former county courthouse that’s lavishly restored to honor him. They hear the history of cotton cultivation and the textile mills thereabouts. They also get educated about other local musicians such as the famous Black bluesman Sonny Terry, a North Carolina native who earned money as a preteen by playing harmonica on the streets of Shelby. The children’s visits have become a regular happening at the Scruggs Center, director Mary Beth Martin said on the phone one October day.

“I’ve got 100 fourth-graders here today,” Martin said. “I want them to understand Earl’s story, that he was a boy who grew up in Cleveland County. Even though he was born almost 100 years ago, his life’s not that much different from theirs and it was certainly shaped in the place where he grew up. I hope they make a connection with Earl. I want them to learn more about his music and feel proud that he came from Cleveland County, and he did what he did in American music.”

It would be impossible to take note of all the impact Scruggs has had, musical and otherwise. But a look back at his history and lasting mark on countless followers fill out the story of a Cleveland County farm boy whose talent took him from Flint Hill to the world at large.

“Good Things Outweigh The Bad”

The Scruggs home place not far from Boiling Springs occupies a lovely piece of broad Piedmont land, as it did during Earl’s childhood. There are plans afoot to restore the run-down house and its crumbling chimney as a further reminder of Scruggs’s achievement. By all accounts, times were hard around the farm and small house, certainly by today’s standards. With the rolling Pigeon River just down the road, it’s a beautiful area, but not one that was thriving during young Earl’s boyhood.

“It went through a great depression back in the late twenties, early thirties,” Scruggs told me in 2007. “It was pretty rough all the way up through the forties, I guess. But everybody was born so poor they didn’t know any better and each year it’d get a little bit better.”

George Elam Scruggs, father to Earl as well as brothers Junie and Horace, and sisters Eula Mae and Ruby, died when Earl was just four. All the children played music, as did George Elam, who played banjo and fiddle, and mother Lula, a church organist.

Earl hung on to memories like that of his dad waking the boys up in the morning with frailing banjo tunes. After George’s death, Lula Scruggs kept the farm going as best she could with the help of the remaining children, those who hadn’t moved on to start their own families. Earl recalled that his chance for any sort of extended music practice was cut into by the time needed for unending chores including “getting the mules their breakfast.”

But even when plowing, he’d think about music, about the banjo, about what he could play, and what he’d like to play. When day was done, he might have time to try out some of the ideas that had rattled through his mind as he worked the fields near the house. He never learned, apparently never wanted to learn, the African-derived downpicking style, or clawhammer, he said. Even though the tones and pulse brought to country string music by Black musicians lived on in his playing, and indeed in all of bluegrass.

The piedmont regions of both Carolinas were home to other players having some success at playing the banjo with thumb and up-picking fingers. But no one achieved the jump from two to three fingers with the impact of the boy from Flint Hill.

Earl Scruggs often described the time he was sitting in the family home, in the mid-1930s, playing the familiar banjo tune “Reuben,” when he realized he’d added his right-hand middle finger to the thumb-and-finger style he’d been playing. He gave me a detailed version in 1998.

‘I Got It!’

“You’ve sat in a daydream like, and be picking and not even noticing what you’re doing?” Scruggs said. “That was the mode I was in. And I was sitting in the, like we’d call this a front room, where somebody’d come in and you’ve got the couch big enough for everybody to sit around like we are and talk, and bring ‘em in here. I was in there by myself one day playing this tune called ‘Reuben’ that I still play, on D. And all of a sudden I had this roll that I still do, going.”

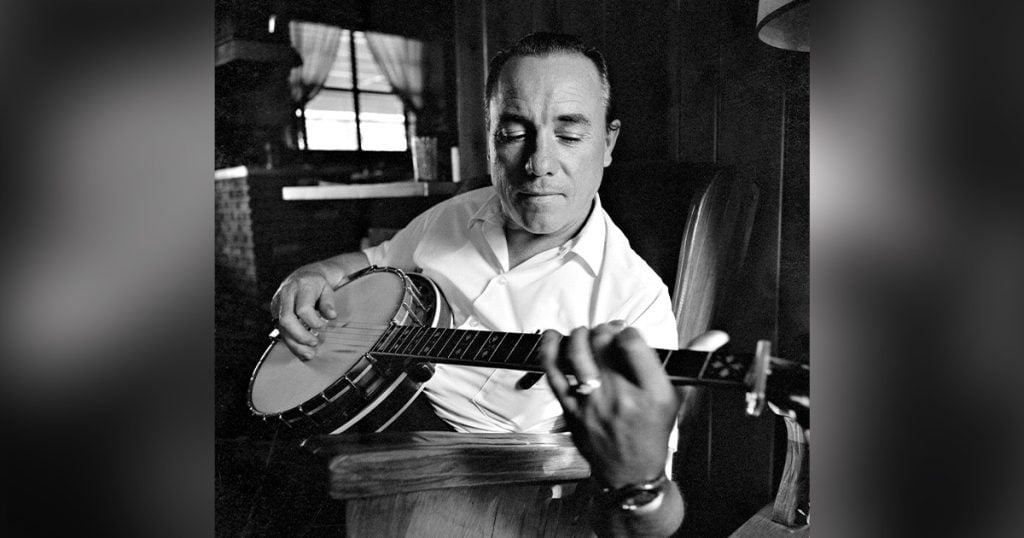

This writer increasingly counts himself as lucky as years march on, fortunate that I got to sit and talk with Earl a number of times, formally and informally. My first visits were to the family home on Donna Drive in Madison, but in this case we talked in the front room of the house where he and wife Louise lived, on a very nice stretch of Franklin Road in Nashville. I wish you all could have been there with us. In addition to being a great musician, a genius in my view, he was also a kind, considerate person, someone who’d look right at the person he was talking to, paying attention to the situation he was in. Earl Scruggs had often told his story about creating his namesake picking pattern, but he still presented it with interest and humor, perhaps even more so when one of his banjo-picking brothers became part of the saga.

“And Horace, my brother, said I came out of the room, said, ‘I got it! I got it!’” Scruggs said. “He said that’s what I was saying. I don’t know what I had, thought I had, but anyway, I played that one tune the rest of the week.”

Rolling On In Music

Young Earl was known to take his studies seriously, learning a dignified cursive writing style and taking an interest in mechanical and agricultural matters. But he also played the banjo wherever he could—at home, at neighborhood gatherings, at talent contests, at fish camp dinners by the nearby riverside, and at a young age, on a radio station at the musical haven of Spartanburg, South Carolina. When “starvation” conditions at the Flint Hill farm led him to start earning a salary at Lily Mill in Shelby to support the family, he played music on breaks with friends such as Grady Wilkie. And it was Wilkie who introduced him to his first semi-professional gig, with the regionally successful brothers Zeke and Wiley Morris, of “On Top of Old Smokey” fame. Soon, a full-time picking gig with Lost John Miller and his Allied Kentuckians became the last time Scruggs played for any act that did not become famous as part of the foundational years of bluegrass.

At the recommendation of North Carolina fiddler Jim Shumate, Earl Scruggs, at age 20, tried out for Bill Monroe near the end of 1945, Scruggs told Jim Rooney for the landmark book Bossmen: Bill Monroe and Muddy Waters.

“Bill came over to the Tulane Hotel and listened to a couple of tunes,” Scruggs said. “He didn’t show much reaction, but he asked me to come down to the Opry and jam some. He showed interest, but I think he wasn’t sure exactly of the limits of it or how well it would fit his music, but he asked me if I could go to work on Monday and I said yes.”

Since his own first Opry appearance in 1939, tall Kentuckian Monroe had been making a name for himself and his Blue Grass Boys band with fast picking and keen, high-pitched singing that combined country string music, gospel, blues, old-timey songs, and some strong original numbers including “Kentucky Waltz.”

Scruggs and Monroe would have a long, electric musical relationship, sometimes including jolts of controversy. The reaction to the chemistry between them among fans and musicians in 1945 was immediate and positive. Wild applause and cheers can be heard on radio transcriptions as Scruggs burned up his solos on numbers such as “Little Maggie,” “Molly and Tenbrook,” “White House Blues,” “Will You Be Loving Another Man,” and “Roll in my Sweet Baby’s Arms.” His playing was startling because it was so fast, so clean and so inventive in terms of rolls, licks and notes. From early, he ventured up to the higher reaches of the fingerboard where few other country banjoists had gone.

Of course, the other unbeatable elements of that Blue Grass Boys band also worked their magic: Monroe’s great tenor singing and wild mandolin, Lester Flatt’s expressive lead vocals and guitar rhythms, Chubby Wise’s bluesy eloquent fiddle and the powerful bass of Howard Watts.

What A Difference A Roll Made

An enduring question about this music has been: Where would Monroe’s music have gone if Scruggs had not showed up? There’s no definitive answer, although it seems likely that an artist of Monroe’s drive and creativity would always have crafted music of power and broad appeal, and would have found players to help express his ideas. Based on events as they transpired, Scruggs is widely recognized as a prime creator of bluegrass music, because the hard racing tempo, syncopation and deep feel of his banjo completed the sound that Monroe had started on its way. For the record, Monroe always believed that bluegrass was born when he debuted the Blue Grass Boys on the Opry in 1939.

Monroe’s opinion notwithstanding,

Opry founder George D. Hay, known as “The Solemn Old Judge,” quickly seemed to identify a prime source of the crowd’s excitement, making special notice of the young banjo player and his new picking style.

“He liked my picking, which was unusual for him, he was such a fan of old style, old-time, ‘Keep it down to earth’ was his slogan, you know,” Scruggs told me in 2007. “But he liked my picking. I remember some of the introductions he had put: ‘Here’s Earl Scruggs with his fancy five-string banjo and brother Bill with “Little Joe,”’ or whatever it was we were gonna do.”

So it was that the music not yet called bluegrass grew popular and spread like a mountain wildfire, but with happier results. That enduring sound of mandolin, banjo, guitar, fiddle and upright bass took shape with Scruggs’s partnership with Monroe and Flatt in the Blue Grass Boys, was echoed by the end of 1946 by the Stanley Brothers, then took off with Flatt and Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys in 1948. As with other Blue Grass Boys through the decades, Scruggs and Flatt departed after finding that the low pay and hard traveling with Monroe outweighed the musical rewards of playing with him.

Beyond the Blue Grass Boys

“Bill was just paying what sounded like a lot of money, but sixty dollars a week,” Scruggs said. “But I was having hotel bills seven nights a week and eating out of restaurants. And back then you didn’t have stay-press clothes. Dry cleaning was extremely high—having your pants pressed. And you wouldn’t sit down till after the show because once you did that the imprint would still be in your pants.”

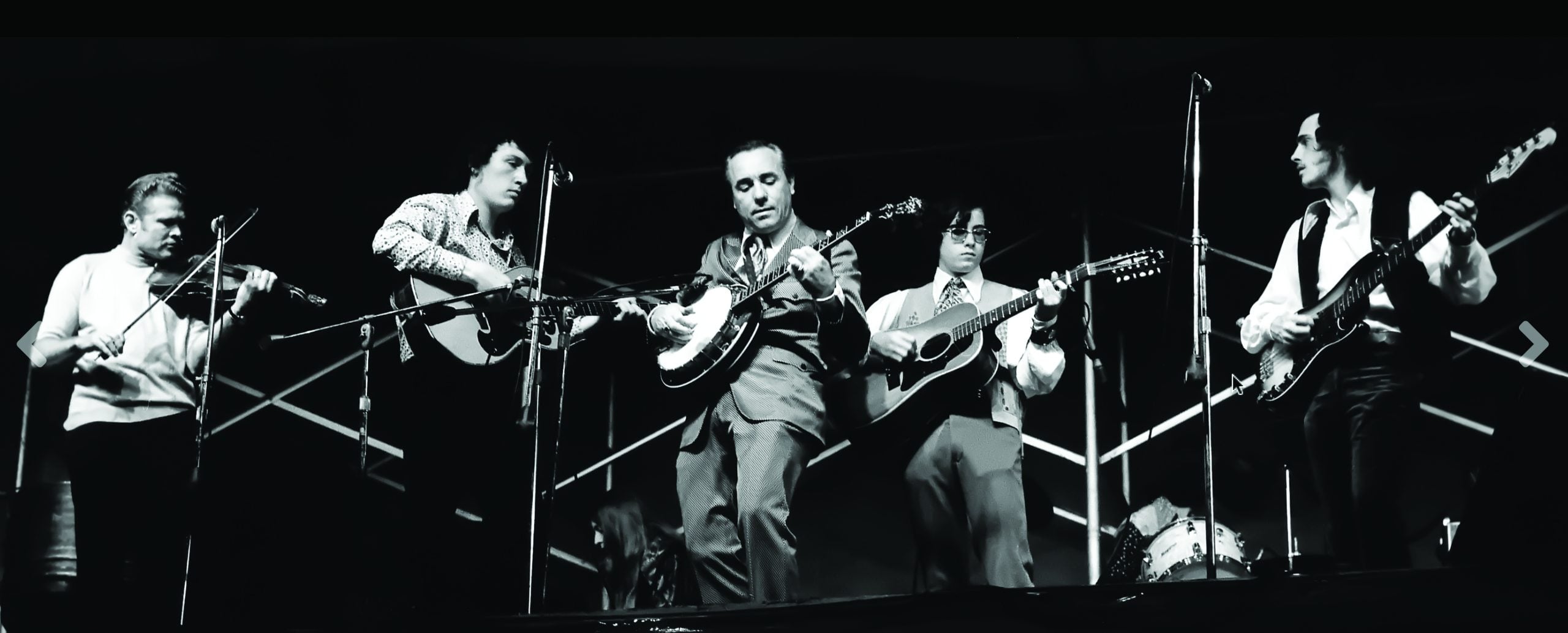

When Flatt also left the Blue Grass Boys, it wasn’t long before they started their own outfit, the Foggy Mountain Boys. Early members included eventual bluegrass vocal kingpin Mac Wiseman and pioneering fiddler Shumate, who had recommended Scruggs for Monroe’s band. They launched a career that would make Flatt and Scruggs the most successful name in bluegrass up until their breakup in 1969. Through this span, they took new directions to make sure they sounded different from Monroe’s band: Earl fingerpicked guitar on some numbers, they featured mandolin less often and eventually discarded it, and in the mid-1950s added Dobro innovator Josh Graves for his bluesy, country-tinged contributions.

But there was no question that in addition to Flatt’s homey baritone, Earl Scruggs’ banjo lived at the heart of this bluegrass powerhouse. In December 1949, the band recorded “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” a Scruggs banjo showcase that would grow in popularity first as a pickers’ favorite, then as the wildly popular theme of the 1967 motion picture Bonnie and Clyde. The sound of Scruggs’s Mastertone in the TV theme to the major network hit Beverly Hillbillies also contributed to escalating demand for the banjo among musicians and fans.

Scruggs Style Spreads in Giants’ Hands

However, that was all to come. Attempts to learn to play it like Earl began almost immediately after his December 8, 1945, debut on the Grand Ole Opry as the new banjo man for Monroe. The fascination started before the Monroe-Flatt-Scruggs band even recorded, and decades before television, instruction books and the Internet brought such new sounds into players’ easier reach. But savvy musicians could tell that something important in string music had happened, and they were determined to incorporate the sound.

Indeed, when the Stanley Brothers were working up their own distinctive sound over in Bristol, Tennessee, Carter Stanley insisted that younger brother Ralph would have to learn Scruggs’s style for the act to succeed in the hillbilly market place. Whether locked into a room, as legend has it, or getting tips from Earl Scruggs in the backseat of a car, Ralph complied and came up with a closely related sound that was his own signature. Like other talented pickers who followed the Scruggs trail, Ralph Stanley was to develop his own trademarks, including the sound of an archtop banjo, a slightly different relationship to the beat, and the use of his index finger to voice melodies instead of Scruggs’s employment of this thumb for the same purpose.

Thus, the three foundational acts of bluegrass—Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs and the Stanley Brothers—each had the driving sound of Scruggs’s banjo—or a derivation of it—at the core of their sound. Years later Scruggs modestly conceded that he was a picker apart when bluegrass got going, playing in a way no one else had mastered.

“Well, I was on the road and I don’t think so, I mean not that was a recording that I heard,” he said. “No, I was about the only one playing that.

“It really turned pickers loose to play tunes. Probably it was the tempo that set it apart a whole lot. I don’t like everything too fast, but you can kind of turn loose on most of those tunes.”

And Scruggs remained the North Star, the reference point to which others would be compared—whether the banjo players who followed Scruggs in the Blue Grass Boys, or those who became central to other bands. As driven academics constantly try to reinvent the study of Shakespeare, or jazz players craft new understanding of John Coltrane, banjo’s deep thinkers about this music talk about previous great players in terms of Earl Scruggs. That comes out in Rudy Lyle: The Unsung Hero of the Five-String Banjo, a good new book in which Massachusetts picker and author Max Wareham discusses the legacy of Monroe sideman Lyle with leading lights including Bill Emerson. (Emerson, a great player and a founder of the Country Gentlemen, died in August 2021.)

How the Style Spread

“The way (Lyle) plays ‘Raw Hide,’ all that stuff, I mean you can tell he sat down and thought it out and plays it the way he thought it ought to be played—not a copy of Earl Scruggs, although I’m sure he appreciated what Earl did, like they all do,” Emerson told Wareham. “Rudy had his own way of playing stuff. He had a different tone than Earl Scruggs. To me, it’s a whole different approach. For instance, J.D. Crowe probably plays his style closer to Scruggs than about anybody else. But he puts his own thing in there, his own trademarks, his own stamp on there, and it’s Earl but it’s not Earl. You gotta bring your own thing into it. Like Jimmy Martin said, you gotta study it out.”

Lyle followed Don Reno in the Blue Grass Boys. Many decades after both Scruggs and Reno emerged on the scene, partisans still argue over which man was the greater innovator. In the 1960s, it seemed for a while as Reno’s freewheeling approach, including jazzy single-string runs, might overtake Scruggs style as the prevailing technique in bluegrass. But it’s Scruggs’s technique that has come back repeatedly as players continue to become addicted to his sound and style. That’s not to slight the impact that Reno made.

“I think Scruggs won the day in popularizing the banjo in the world,” the great banjo player and historian Alan Munde said. “Reno had his accolades, but…I will say, Reno’s many techniques, famously including the single-string approach, but also his chordal approach on slower songs (his genius), have been a very strong model for the newer modern players to emerge following in the path of Béla Fleck. They seem to have heard the sense in Reno’s wide-ranging approach, but with the years in between Reno and now, have polished those techniques to a high art.”

When J.D. Crowe, another titan of the instrument, talked to Frank and Marty Godbey, for a 1976 Banjo Newsletter story, he mentioned the generation of players including Sonny Osborne, Allen Shelton, Hubert Davis and, when prompted, Rudy Lyle. “And the pros were Scruggs and Reno and Ralph (Stanley) as far as three-finger pickers; I guess that was about the crop,” Crowe said.

And what got Crowe started in country music? the Godbeys asked. “Well, of course it was Flatt and Scruggs,” Crowe said, recounting his experience of seeing the act in Lexington, Kentucky. “I was into country music and rhythm and blues. I was sitting there one night and they introduced this new group which I’d never heard of at the time. Five guys came out and just tore the house down and me with it. I couldn’t get over it! All I’d heard of the banjo was frailing, clawhammer, which I really didn’t like (of course I can appreciate it now, more than I did then), But I never heard a sound like that.

“That’s what inspired me to play the banjo. It was the drive, the rhythm. You could just feel it. It seemed like to me that everybody in the whole place came alive when they hit the stage. That was the fastest half hour I ever spent in my life; seemed like five minutes. That was in 1951.”

Just five or six years after Scruggs’s debut with Monroe, bands were coming up with creative new sounds, but all of them kept a banjo player using three-finger style as a central component. Monroe unleashed powerful new harmonies with Jimmy Martin as a duet partner, while breaking more ground with Lyle’s individual style and Vassar Clements’ fiddle innovations.

Shelton’s singular approach, with its trademark “bounce” and the influence of steel guitar, would become part of the hit sound of Jim & Jesse McReynolds a few years later. Sonny Osborne, another innovator of the period, also cited Scruggs as a mentor, and eventually a friend. Like a number of other followers, Osborne preferred Scruggs’s playing from the early years.

“Nineteen-forty-seven to 1955 was my favorite time,” Osborne said in his “Ask Sonny Anything” column in Bluegrass Today. “He was better then, and even now during that time period no one has mastered the banjo as he did. And I studied his playing, especially his right hand, so that I can honestly say it has influenced my playing. I liked his mannerisms, and the way he carried himself, as well as the banjo.”

‘Big Mistake’

As the banjo began to spread in popularity through the 1950s and ‘60s, players finally had the means to learn Scruggs style through means other than repeated listenings to recordings, often using a slower speed on a record player’s turntable. Folk leader Pete Seeger included a brief section of Scruggs style in the banjo instruction book he first compiled in 1948, then reissued periodically until a 1962 version sold 100,000 copies.

An instruction book under Scruggs’s name came out from a mainstream music publisher, but contained incomplete renderings of the tunes, the influential banjo player Bill Keith pointed out to him. In a series of events that sheds a questionable light on the business practices of Earl and Louise Scruggs, Keith worked at length on an accurate reworking of the information, using tablature instead of conventional notation, he said in an October 19, 2007 interview with Nick Barr at the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries.

“When I did finish work on the book, Earl is the one that shook my hand and who gave me his word that when the book started earning money that I’d be getting a share of it,” Keith told Barr. “And, well, here’s my hero shaking my hand to give me his word. And so I didn’t ask for anything on paper. Big mistake. Big mistake. Of course, later on, Louise is the one that told me, ‘Hey, take a hike.’”

As Fleck once told me, “Earl wasn’t Gandhi,” but he never generally became the subject of the sort of negative personal lore that was attached to Monroe, Jimmy Martin, Carter Stanley and others. As manager and sometimes hardball player, Louise Scruggs deflected some of the jealous attention that greeted Flatt and Scruggs when they far exceeded the success of any other bluegrass act of the day. Louise carefully guarded the kinds of dates and venues that the duo, and later Scruggs, agreed to take on. She initially opposed their Beverly Hillbillies connection until she made sure it wouldn’t portray Lester and Earl as ridiculous backwoodsmen. Indeed, appearances by “Lester and Earl” on the show often made them look wiser and hipper than the characters of either the Clampetts or the Hollywood bigwigs.

While Bill Keith spoke frankly about the raw deal he got on the Scruggs instruction book, he also gave Scruggs credit for sparking his interest in banjo technique. “The first thing I heard when I set the needle down in the Earl Scruggs record Foggy Mountain Jamboree was the sound of the banjo being detuned and retuned, and I thought, ‘What is going on here?’” Keith said in the Barr interview. “And it was a little disconcerting at first, but I got used to it pretty quickly and decided that was just the way things ought to be, (and) what I wanted to learn to play.”

Along with South Carolina-born picker and session man Bobby Thompson, Keith went on to become a key exponent of what came to be called the melodic banjo style. These players used specific fingering and string choices that allowed for more exact, flowing replications of fiddle tunes. The style became broadly popular, but over the long haul has become a tool of many top players, not a replacement for Scruggs’s basic technique.

So compelling has been Scruggs’s sound that a succession of influential players cite their first hearing as a transformational experience. Better known as the great guitarist who founded the Grateful Dead, Californian Jerry Garcia fell under the Scruggs spell in about 1960, before the Beverly Hillbillies or Bonnie and Clyde. “I didn’t really start to get serious about music until I was 18 and I heard my first bluegrass music,” Garcia told an interviewer. I heard Earl Scruggs play five-string banjo and I thought, that’s something I have to be able to do. I fell in love with the sound and I started earnestly trying to do exactly what I was hearing.”

Notable banjo man Doug Dillard said he was jarred to his foundation by his first hearing of Scruggs: “I was driving down the road with the radio on,” journalist Randy Lewis quoted Dillard as saying in a 2012 obituary. “All of a sudden I heard this incredible banjo music. I got so excited that I drove off the road and down into a ditch. I had to be towed out.”

Born in 1937, Dillard was in touch with Scruggs not long after his 15th birthday, asking Scruggs via a letter whether he was too young to learn the banjo that he’d gotten as a Christmas present. Scruggs’ positive response sent Dillard on the road to a long, impressive career.

North Carolina banjo great and expert Jim Mills was only five or so when he was transfixed by the sound of Foggy Mountain Breakdown coming from a record player in a neighboring room. That’s all it took. Mills has gone on to earn multiple IBMA and Grammy kudos while in various bands, notably that of Ricky Skaggs, and as a solo artist and session musician

Meanwhile, Noam Pikelny, a star of a more recent generation of banjo pickers, credits the role of Scruggs even while playing a style that combines Earl-isms with melodic and other approaches—essentially using whatever technique best suits the music at every turn. Nonetheless, in an explanatory video, Pikelny said: “When you hear Earl Scruggs play the banjo, it’s what the banjo is supposed to sound like.”

And Kristin Scott Benson, multiple IBMA banjo player of the year award, commented in 2012 to Bluegrass Today on the puzzle that greets today’s pickers: how to move forward while always being measured against Scruggs’s standard. “For many listeners and players alike, your worth as a bluegrass banjo player is gauged by how closely you can emulate what Earl did back in the late 1940s, 50s, and 60s,” Benson said. “I’m not aware of any other instrument, in any other genre of music, that places such a strong emphasis on recreating the past. Perhaps it is because Earl set the standard so high, that it is quite simply impossible to reach or surpass. This is what sets the rest of us on a lifelong pursuit with the beloved instrument that Earl Scruggs introduced to the masses.”

A Certain Something

Something indefinable about Scruggs’s playing connected to future players’ hearts and brains, a mysterious impulse that compelled them to overdrive their fingers and minds as they struggled through learning the banjo. It could have been the full, round sound of every note he hit, the adept fingering, slurring and pulling off by his left hand, the incredibly coordinated, alternating picking of his right-hand fingers, or some unearthly combination of all that. Many great players took Scruggs as a starting place, but no one ever sounded exactly like that.

There’s much more of Earl Scruggs’s career to relate: His famous later years with Lester Flatt, the popular success of the rock-influenced Earl Scruggs Review he formed to fulfill his goal of working with sons Randy, Gary and Steve; the stacks of awards and honors; his star-studded solo recordings and videos; and even the deep mourning and packed Ryman Auditorium funeral that followed his death in 2012.

Inevitably more pickers and fans will make new discoveries of the treasures that remain in the many recordings and videos of his playing. In addition, there will be notable news to come about the community-building work of the Scruggs Center and the successful new festival that bears his name. The appeal of his playing appears undying. At the 2022 inaugural Earl Scruggs Music Festival, Béla Fleck gave an unusually detailed account of his conversion moment, so like that of other musicians who had their banjo switch flicked on by Earl.

“It happens when you hear Earl Scruggs, at least for me, even growing up in New York City, no connection to bluegrass, country music, folk, anything, just a New York City person,” Fleck said. “I heard the sound and it was the Beverly Hillbillies. And people laugh about that, but to me the banjo was quite serious on that song. It was not a laughing matter. It was like, wow, you finally focus. It caused my brain to focus exactly. It was going everywhere at four or five years old. And suddenly I realized what was important in life. I had to go get a mentor because it didn’t seem like anybody could do that. Because I couldn’t see it, I could only hear it and it sounded just so, you know, computer-perfect and yet there was so much soul in it. I always think about it as a primitive, high-tech sound. And never, never attainable.

“But from then on, I was banjo-aware, where things happen like, you’d see a banjo, somebody playing it at the farmers market, in upstate New York, or you’d hear something on TV, and it would be okay. But then every time Earl Scruggs would come back on I’m like, ‘Whoa,’ and so I don’t know what it is that he really had, maybe we can talk about what that was for you.”

The Scruggs Festival workshop gave a crowd of fans a chance to hear reflections on Scruggs by Fleck and resonator guitar hero Jerry Douglas, who also said he started out wanting to “be Earl Scruggs.” After relating his moment of revelations, Fleck told of finally encountering a succession of teachers, picking along at downtown coffeehouses, reaching a certain level as a player, then moving to Kentucky to make sure he was learning the real deal. Along the way he realized he wasn’t alone in his being caught up in Scruggs: “I know I’m weird,” he said of this period. “It’s okay, I’m weird. It hit me and then I discovered there was a community out there that had the same reaction, that tried so hard to play like Earl.”