Home > Articles > The Archives > Deacon Dan Crary: A Man of His Own Cloth

Deacon Dan Crary: A Man of His Own Cloth

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1974, Volume 8, Number 11

“Deacon Dan” Crary is perhaps theology’s best-known contemporary bluegrass musician. Other professions, of course, have their representatives in the Bluegrass Hall of Fame … John Starling operates for the medical doctors, and commercial artists can boast Mike Auldridge (both of the Seldom Scene). But there’s something almost awe-inspiring about having a real theologian in bluegrass’ midst.

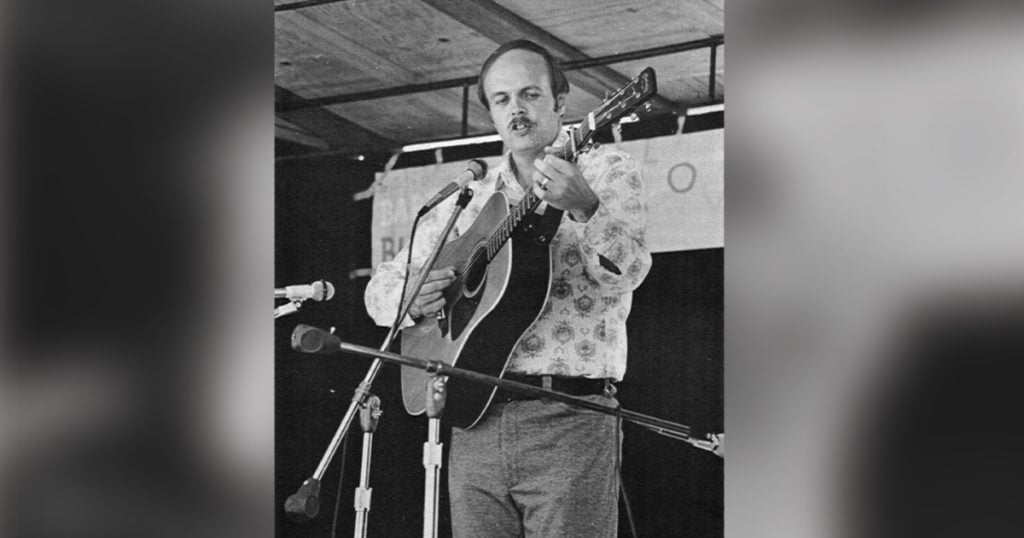

It’s not always easy to match a bluegrass performer with his profession on sight alone, and there aren’t a lot of rules-of-thumb. You sort of have to go by instinct. For instance, it’s easy when you see Deacon Dan on stage, generally picking and singing in solo, to tell that he’s some sort of messianic figure. For his nose projects straight and narrow-tipped as the Gospel Truth, and his deep broad forehead stretches across what becomes easily recognized (as soon as Dan opens his mouth) as the Wisdom of Solomon. The real giveaway, however, is his guitar flatpicking which sounds as clean and wholesome as if it had just been baptized in the River Jordan!

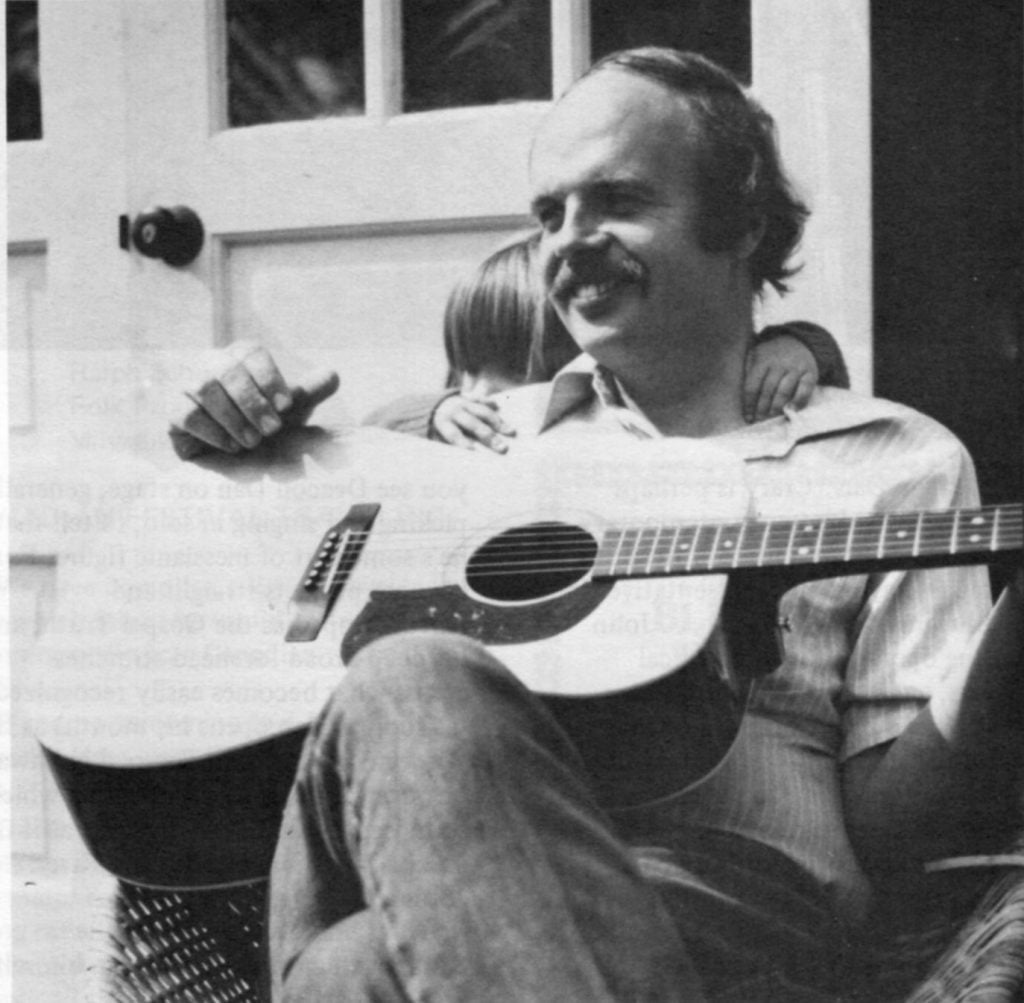

What better way to greet the Sabbath than with the Deacon himself at a late Saturday night after performance picking party! Already assembled are the usual assortment of Crary worshippers including well-known pickers, not-so-well-known pickers, and (pray-for-them) would-be pickers.

“Excuse me, Deacon. We’d like to do an article on the connection between bluegrass and theology in your life.” (I did wonder if it would not be more appropriate to address him as “Reverend”, but I guess “Deacon”, when combined with “Dan” offers more alliteration).

“I’m not studying theology. Haven’t been for about four years.” I moved closer in disbelief to get a better look. Come to think of it, he didn’t look at all like a theologian.

While listening to his album at home, I had always pictured him dressed in clerical garb like I once saw Peter Sellers wear in a movie — flowing black robe and a wide-brimmed hat that looked like an inverted offering plate. This guy was wearing blue jeans!

But wait… On second thought, maybe somebody who spent nearly half his life until he was 30 working toward a theology degree has the right to keep a little vestige title like “Deacon”.

Dan put in his time, and he deserves the title “Deacon”. I mean, first there was Moody Bible Institute in Chicago right after high school; then Golden Gate Baptist Seminary in California for his Bachelor of Divinity (not his Bachelor of Arts — that he got at the University of Kansas in between); and finally there was Southern Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky where he went to get his doctorate in theology.

I conjectured (correctly I later learned) that it was while he was studying at the seminary in Louisville that Dan joined up with the Bluegrass Alliance then made up of such secular members as Lonny Peerce, Buddy Spurlock, Ebo Walker, and Danny Jones. They all played at an establishment called the Red Dog Saloon.

“Why did you leave the seminary?” I asked wondering if the environment in which he played and the company he kept had any influence on his decision.

He explained it this way: “I was sort of headed in a direction religiously when I got out of high school, that I feel now like I had to work my way out of. And the way I was able to do that was by trying it and finding it didn’t work. But the theological (barren market) teaching job situation was what ultimately made up my mind.”

So, at the age of 30, feeling that he had come to the end of a road, Deacon … a wiser man … felt that with about a third of his life trickled away, he must expend what time he had remaining as carefully and economically as possible. Knapsack on back, guitar tucked under his arm, he left Louisville (and very reluctantly the Bluegrass Alliance) and headed back to Kansas to secure his Ph.D. in Speech Communications (public speaking, small group communications, and human relations) and raise a family.

The course of study he chose for his doctorate was, it seems, following a natural instinct that had shadowed him for 15 years. Beginning with the time he was selected at Moody Bible Institute as a suitable “mellifluous sounding greenhorn” to break into radio broadcasting, and everywhere he went from there on, he always had a radio (disc-jockey type) job on the side.

As he talks, the real Dan Crary sitting cross-legged on the floor before us at the picking party emerges as a communicator of ideas. The physical traits are the same, but the emphasis is different. The nose guarded by thoughtful, philosophical eyes appears now to be more aptly described not in religious lingo, but as “straight-to-the- point”. And the broad expanse of forehead houses a mind that could best be labeled as always running—constantly thinking, exploring, questioning, taking-in, in keeping with the race it appears to be running with time.

A friend at the party affirms this as he offers his own commentary on the Deacon: “He works like a damn dog! I’ve never seen anybody work so hard in my life!”

There’s Dan’s present occupation of studying for his comprehensives (which hopefully he will have passed by the time this article appears). Then there is his thesis to be completed. As an additional challenge he teaches a freshman speech class and coaches (and travels with) the debate team. Keeping up with the tradition of disc-jockeying, there’s his bluegrass radio program for one hour every Saturday night, and for 5 months out of the “summer” he works full-time as a country-western record spinner (which requires jockeying classes and other activities as well as discs in late spring and early fall).

Among these activities there is no allocation of time for practicing and performing bluegrass! The wonder of it all, from the haphazard way he goes about pursuing (or non-pursuing) his music, is that he has developed a style so unique and technically perfect as to thrust him into the company of the select few who sit atop the guitar flatpicking flagpole. Perhaps the reason for this almost accidental success lies in his motivation for playing bluegrass.

“Music is not fun in the sense of FUN to me. I don’t mean that it’s the opposite of fun, to me. It’s more something I have to do. It’s something that’s happening inside.” (It has been happening inside ever since he first heard a Stanley Brothers record in 1951 “and went completely bananas”, and become what he thinks was probably the only kid in the whole state of Kansas to know that bluegrass was not something you grow out in the fields.)

“I like the tonality of bluegrass — the pure chord forms and the harmony. The cliche’s that happen in bluegrass are my cliche’s. Something magic happened when they got these 5 or 6 instruments together. The total is more than the sum of the parts.”

Listening to him speak, it is clear that Dan’s music is primarily a form of personal release translated into a high art form. He usually picks up his guitar around 1:00 or 2:00 A.M., after all his other work is done, and plays for an hour or an hour-and-a-half. It is during this period that his concepts and his feelings become the reality of his bluegrass music.

Last summer his promoter wanted him to write a bluegrass flatpicking manual (which you may have seen advertised under the pseudonym of Deacon Crary). “I’d get home at 1:30 or 2:00 in the morning from (radio) work and sit down and write until about 8:00 in the morning.”

“Aside from the 22 years I spent thinking through what I might do in such a book if I ever got around to writing it, I did the whole thing in 8 days. It’s about 70 pages long and consists of tablature, notes, and music. It’s for people who are not stone beginners, but who already know something about the instrument. It will get people started playing fiddle tunes on the guitar. It will not teach them much about the flatpicking technique itself. Book 2 will go into that.”

As if just talking about the work that went into his flatpicking manual exhausts him, Dan, already tired from the strain of the concert and sleepless nights of travel, starts to doze off, despite the party commotion around him.

“How much sleep do you usually get, Dan?”

“I have to have at least five hours or else I just can’t crawl”.

“How do you survive on five hours of sleep?”

“I eat a lot of vitamins and I play bluegrass. The vitamins are to take care of what the bluegrass does to me.” (That’s probably the most profound and the truest statement of the evening.)

The not-so-well-known pickers, and especially the would-be pickers are getting restless for Dan to take up his guitar. Finally someone starts playing a Dan Crary cassette tape recorded at a festival last summer. As he talks about his ideas here in person, and as he talks between songs on the tape, it is obvious that Dan is in many ways fascinated with details and nuances — in short he is a perfectionist. One would have to be to carry off flatpicking with the precision which is his trademark. It is no surprise, therefore, that his favorite kinds of songs are those which depict in detail small towns and the stories and happenings there. “Stagalee” is one such song that reels by on the tape.

After listening to it for a moment, his eyes light up, suddenly awake as he talks about a new song he found “that’s got all sorts of interesting people in it. They’re called Denver Kish and Lyla Bene, and there’s a place called “Trudy’s Bar, and it’s like a Tennessee Williams slice of life. I like lyrics that either tell a good story or that have something authentic to say about personalities.”

But what is perhaps the most interesting thing about Dan’s presentation is the introductions that carry him gently into songs while his pick is wandering over the strings to create a mood. As he talks he paints a setting with words, and then he completes the picture with the song and the music. It is the essence of his style, and it is clearly the way Deacon Dan Crary communicates his bluegrass.

The real question is: What next? If he follows his natural instincts, will he be able to keep shoving bluegrass to the edges of his life (as he tried to do with communications for 15 years) and keep his music relegated to middle-of-the- night prowlings? Or, will his music eventually force itself into a dominant position in his life? Dan’s current aim is to become a college professor. But when asked if he has ever considered devoting more time to his bluegrass, the answer is a ready “yes”.

“When I get out of school, my object is to teach college. But I’d like to do something that gives me more of a chance to play music. If I can mix the two somehow, I’m going to try to hit a happy medium. I don’t have anything visualized, but I’m saying that I have an open mind about it.

“I guess I feel the compulsion to kind of get next to people and find a common ground with them and share emotional experiences. I think that’s how people communicate. They become more and more intimate on the basis of shared experiences and their feelings, and I think music can do that. I insist that bluegrass music is one of the art forms that is capable of communicating just as profound emotions as painting or drama or any of the so-called ‘great arts.’ ”