Home > Articles > The Archives > Buzz Busby: A Lonesome Road

Buzz Busby: A Lonesome Road

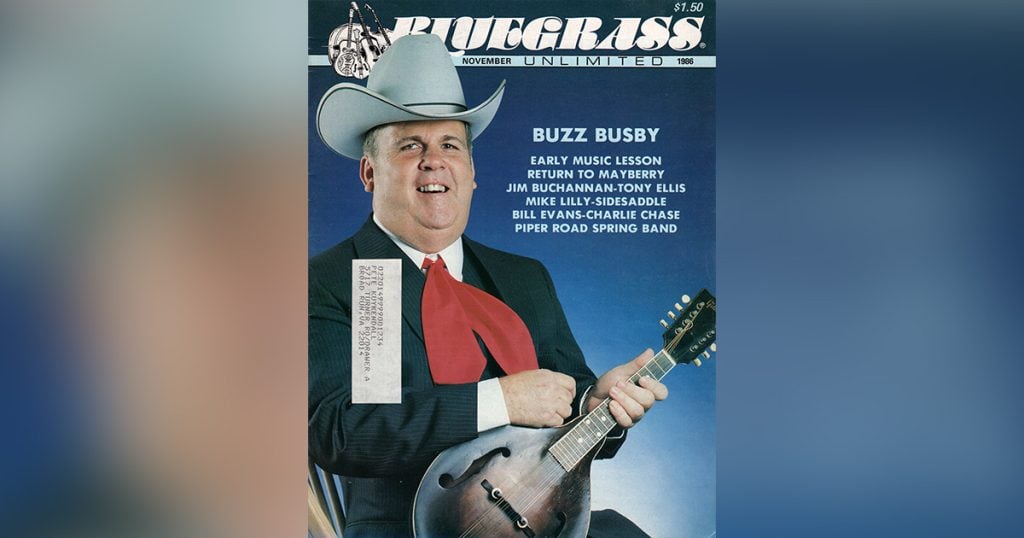

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1986, Volume 21, Number 5

In bluegrass, those who have given their lives to the music often become casualties of the music, forgotten and buried when they fall from the top, while the crowds turn to some sharp, hot new group. Often the casualties of the music are those who lived the music a little too passionately, a little too close to the gritty reality of what many of the songs are about.

One of these pioneers who fell by the way precisely because his life turned out to be so unbearably like the songs, does not deserve to be forgotten; if for no other reason, everyone should hear what he created: some of the most pain-filled, hair-raising, hard-core lonesome bluegrass songs, formed directly out of his own raw, difficult life. But there are other reasons beyond that; Buzz Busby played a major part in the formative years of Washington, D.C. bluegrass, and in the over thirty years since then, has helped many musicians on their way and given them their start.

Buzz Busby was born on September 6, 1933, in a small town called Eros, near Monroe, Louisiana. The youngest boy of nine children, he grew up on the family farm, about fifteen miles from the community of Cheniere where Webb Pierce lived. Some of his older brothers went to school with Webb Pierce and the family later listened to Webb on the Louisiana Hayride, as well as to other country and western swing artists such as Bob Wills on records and on local radio programs.

By the time Buzz was a teenager, the country music played in Louisiana bars and on local radio was quickly changing from sweet songs about cabin homes and mother to a music filled with the complexities of a changing urbanized world: lonely disillusioned songs about cheating and divorce and getting into trouble; as well as rollicking good time drinking songs. It was these crying-in- your-beer honky-tonk sounds that Buzz heard on the radio as a teenager, and when he began playing in bars; it was honky-tonk that would later become the very core of not only his unique musical style, but of his own life. But before he heard this music, he heard bluegrass, and bluegrass has always remained his first love. Buzz would later fuse a traditional high, lonesome bluegrass voice and an unusual soulful mandolin style with the lyrics and heartfelt pain of honky-tonk in a way that no one else has ever done.

Typical of the rebellious need to prove himself that characterized most major moves in Buzz’s life, Buzz first heard bluegrass in a twelve-year old fit directed toward his mother. The family gathered around the radio every Saturday night for the Grand Ole Opry. They listened to Roy Acuff (who Buzz calls his “first idol”) on the Prince Albert portion every week, and after this show, Buzz was sent off to bed. One night he insisted on staying up later, just to prove to his mother that he was no longer a child, and he heard for the first time, on the Wall Right show, Bill Monroe. It was Monroe’s classic band that he heard —Lester and Earl and Chubby Wise and Cedric Rainwater—and it was something he never forgot. He listened every Saturday night after that. “That was it. I didn’t care for nothing else; didn’t want to hear Carl Smith or nobody. I was strictly a fanatic. It got to where that was the highlight of my week. If something was to happen and Bill Monroe wasn’t on there, I’d be mad all week.”

“If I Should Wander Back Tonight” was Buzz’s favorite song, as well as “Love Grown Cold,” “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” and “Kentucky Waltz.” Then one night he heard, “Shine Hallelujah Shine,” and it “made his hair stand up.” He was hooked more than ever when he heard “Wicked Path of Sin,” but it wasn’t just the singing that drew him like a magnet; it was the mandolin. Buzz remembers that “it sounded like the harps of heaven. It sounded beautiful to me.”

Buzz had seen a mandolin before; a neighbor named Allen Crowell used to bring one over and play, and he had also heard it in church, in gospel groups. And he had heard Bill Nettles who took Joe Shelton’s place with the Shelton Brothers on a local radio program out of Shreveport, Louisiana. He had also heard mandolin players with the bands on The Louisiana Hayride early mornings before he went to school: the Bailes Brothers, Johnnie and Jack. And he had even heard Bill Monroe himself playing mandolin on Monroe Brothers records they had at home. But he had never heard it played like Monroe was playing it with the Blue Grass Boys on the Grand Ole Opry. Buzz recalls: “Back in those days Monroe played pretty fast; the hottest mandolin playing I ever heard, and I haven’t heard since. His mandolin playing was heavily influenced by a jazz mandolin player named Paul Buskirk, and I haven’t heard him play like that again—or maybe I was just easily impressed then.”

This could be; it is possible that Buzz’s own style, which many mandolin players have tried to copy and can’t, became so complex that no one’s playing could ever impress Buzz again. Buzz came to his own mandolin by way of the guitar, and came to the guitar by, once again, a rebellious and competitive drive to prove himself. At first, he wasn’t really interested in learning how to play music, although “every house had a fiddle or guitar,” and two of his own older brothers, Wayne and LeMoyne, were playing guitar-fiddle duets and singing Monroe Brothers harmonies around their community. But one day, when he was still only twelve, a boy who lived down the road and went to school with him, came over with his guitar and hit a “D” chord. Now, Buzz was a very good student, making excellent grades, entirely because of prodding and pushing from his mother, who was a teacher and came from an extremely college-oriented family. This boy with the guitar made low grades. And while Buzz watched him plunking out guitar chords, he thought to himself, “If he can do it, I ought to learn how to do it.”

Buzz went to his brothers, Wayne and LeMoyne, and asked them to teach him, and he quickly learned guitar chords and the Lester Flatt run. Around this time, Wayne went off to live with an uncle to get a better education than could be had in their small town, and LeMoyne, who played fiddle, was left without a guitar player. Eager to get a replacement for Wayne, LeMoyne taught Buzz how to back him up by pointing the fiddle bow at him whenever it was time to change chords, this is how Buzz learned rhythm guitar.

“I didn’t dream I had any talent at all,” Buzz says. But by the time he was fifteen, he was playing professionally for $5 a night. Wayne was back home then, and the three brothers played with their cousin Billy in churches, home dances and parties, and bars. At this time, Buzz had not found that distinctive high tenor voice, and sang baritone. However, he had found the mandolin.

The mandolin came to Buzz indirectly through his competitive streak that he readily admits to. He figures this fighting attitude came from his mother pressuring him to get good grades, and also from being the youngest boy. “I insisted on excelling and beating everyone,” he says. Buzz had been working since he was seven on the 360 acre self-sufficient farm his family shared with an uncle’s family. Buzz worked hard at picking cotton, their cash crop, not to make a lot of money, but to show up his brothers who teased him for being so little. He was “determined to kick everyone” and beat them all at picking cotton. He never saved for a mandolin, although he knew he would like to have one, but through his determination at beating everyone, he found himself with some extra money. At the age of fourteen, he sent away for his first mandolin, a Silvertone from Sears for eight dollars.

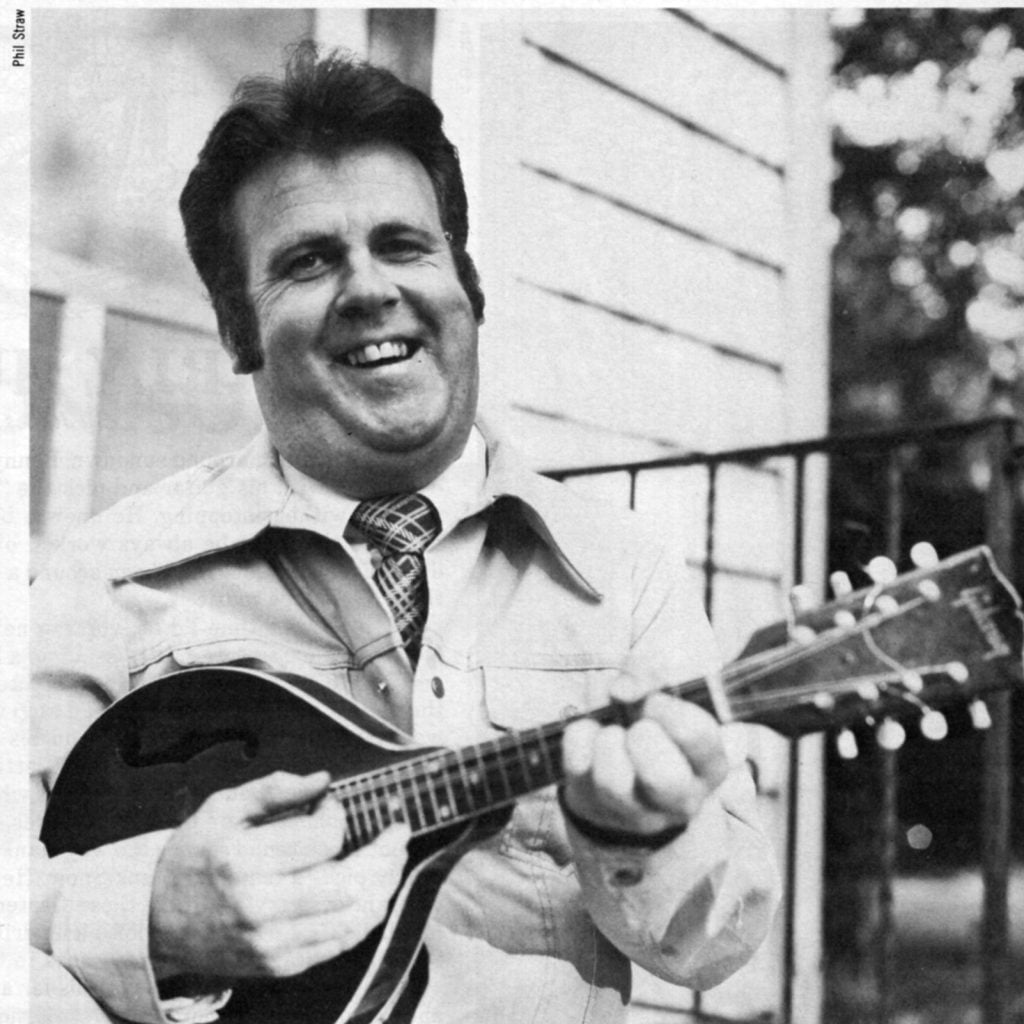

Buzz at first copied Bill Monroe note for note. He would spend hours with the mandolin until he mastered a song like “Kentucky Waltz” or “Bluegrass Breakdown” which he learned from records. The only instruction he received was from the local mailman, Wendell Saunders, who would sometimes stop in and teach him tunes like “Soldier’s Joy.” Soon he was learning the neck completely on his own, and going off in his own direction. He estimates that by the time he was sixteen he had already developed his unique fiddle-like mandolin style: a style that uses lots of double stops and draws out a succession of rapid down-up strokes longer than most mandolin players have the strength to sustain, creating an uninterrupted roll, like the sound of flowing, rippling water.

Buzz says by the time he was nineteen and playing with Mac Wiseman, he “could play better than most mandolin players can play now. I developed my style out of what sounded pretty to me. I wound up doing complicated things with it, but I didn’t do it intentionally; I did it because it was pretty. Yet other mandolin players can’t comprehend it. It’s beyond my comprehension. It doesn’t seem like it should be that hard. I guess I was way ahead of my time.” Besides Bill Monroe, no other mandolin players have really influenced Buzz’s style; but he was influenced by fiddle players, mostly Benny Martin. In fact, he played the fiddle himself when he was eighteen, but the first time he heard Scotty Stoneman, he gave up, saying, “what the hell, I can never beat him.”

While in high school, Buzz played three nights a week in clubs with names like “Rest-A-While,” “The Blue Goose,” and “The Tornado.” He says these clubs were like “going back to the wild west. It was like taking your life in your own hands just going in there.” But contrary to popular myth of chicken wire protecting musicians from bottle-throwing audiences, Buzz remembers that the crowds never bothered the musicians on stage, they just bothered each other, and that “they’re worse up here [Washington, D.C.] than down there.” The roughest clubs Buzz would know came when he moved to Washington in 1951, after graduating from high school.

With his good grades, Buzz graduated as class valedictorian, and received a partial college scholarship. However, Buzz’s mother, who had been experiencing hard times since the Depression and the death of Buzz’s father when Buzz was only nine, could not come up with the extra money needed for college. In spite of their lack of money, his mother, believing that education was more important than anything in the world, insisted he enroll in Louisiana Tech, and not worry about the money, having the faith that it would come from somewhere, somehow. Buzz speaks wistfully about his mother’s optimism, and says he didn’t have the faith she had that he would somehow get through college without a job and only a partial scholarship. An FBI recruiter came through his high school just at this time, and the pitch for a secure income and stable position as a fingerprint technician, with the potential to become an agent, looked good to Buzz. He decided in his independent way that he wanted to move to Washington and make his own living and send his mother money whenever he could. But he didn’t forget education, and enrolled in George Washington University in Washington while working full-time for the FBI, as well as taking FBI training courses.

Buzz also didn’t forget music. In fact, it quickly became the most important thing in his life. When Buzz came to Washington, D.C. in 1951, at the age of seventeen, bluegrass was no more popular in this city than anywhere else, but Buzz would soon change that forever. Many people today credit Buzz with being one of the first to popularize bluegrass in Washington. Indeed, the list of bluegrass musicians who played for Buzz over the next twenty years after his arrival sounds like a who’s-who in early Washington bluegrass. Even after 1972, when Buzz lost his high voice and hit bottom with his bluegrass musicians, old and young, and had a prominent hand in getting nearly every member of the Johnson Mountain Boys started in bluegrass during the late seventies. His influence can be heard in their music, especially in Dudley Connell’s compositions and in their first album.

But when Buzz first came to Washington, the closest thing to bluegrass was the Stoneman family. Buzz and Scotty Stoneman quickly took to each other and teamed up in a touching, brother-like on-again, off-again friendship and musical partnership that would go on for the rest of their days together (Scotty died in 1973). Scotty’s intense, passionate fiddle was the perfect match for Buzz’s equally passionate mandolin style, and their relationship, always marked by boyish bickering and spats, as well as an unspoken closeness and togetherness, was one of two alike souls, tormented and driven. Buzz now recalls the only time Scotty ever came close to admitting to their comradeship, was one night when he said, “You know, my fiddle playing is just an extension of your mandolin playing.” Buzz laughs about this now, pleased, and says this was the kind of thing Scotty could only say in private, never in front of others. His ego wouldn’t let him. Buzz remembers not replying to this remark, because he wanted to stay one up on Scotty. He also remembers in later years, when Scotty depended much on alcohol, that he would often play on a recording session with Buzz, and not charge a cent. He did this because Buzz let him play the way he wanted, something no one else would do. “I wanted him to be a free spirit. I don’t like to hold a man back. I don’t like to be held back.” Many times Buzz would pay Scotty in liquor, the only thing he would accept.

The two met as teenagers: Buzz was just eighteen, and Scotty was nineteen. Buzz lived in Hillside, a Maryland suburb, near Carmody Hills, where the Stoneman family lived. Buzz had a girlfriend also living in Carmody Hills, who knew Scotty and kept saying that Scotty had heard of Buzz, had heard his playing somewhere and liked it. So he went to a club, where Scotty and Pop Stoneman were playing, and Scotty fiddled all night to Buzz to impress him. Buzz laughs about this, and says Scotty was a real wheeler-dealer back then, and as soon as the show was over he approached Buzz and asked him to play guitar with his band, having in mind that he eventually wanted him to take Frank Dunsmore’s place on mandolin. But instead, Scotty formed a band with Buzz and Jack Clement.

Every Sunday, Scotty and Donna Stoneman would go to Buzz’s house. “Donna was wanting to learn the mandolin at this time, so I taught her quite a bit, got her started, and she took it from there.” Buzz remembers fondly his early days in D.C., meeting the Stonemans and playing music, living in a nice house with his mother and sister, who had come up to live with him for the summer, and says wistfully, “That was a very happy time of my life then.”

It was through Scotty that Buzz met Jack Clement, another musician who would come in and out of Buzz’s life over the years as a music partner and close friend, later helping him out in Nashville when Buzz was close to rock bottom, while Jack had become a well-known songwriter and record producer. In their early days together with Scotty Stoneman, Roy Clark joined them for a while on banjo, and this band played what was possibly the first bluegrass in D.C., outside of what the Stoneman family was doing. Buzz began finding his chilling high tenor with this group, while Jack sang lead, and Scott sang baritone. They were quite advanced for bluegrass at this time, with strong harmonies and super picking.

Buzz recalls that jobs were plentiful around D.C. in 1951 and ’52. His band was playing four or five nights a week, while he continued to work for the FBI and go to school. Eventually he was making more money at playing music than at the FBI, so he quit. He also dropped college from his busy life at this time, to devote his energy full-time to music. He was so ambitious that after only a few months of playing together, he and Scotty and Jack decided to go to the Grand Ole Opry and audition. He laughs now at their naivete and says the people at the Opry treated them very politely when they turned them down, but probably laughed at their audacity after they left. This did not deter them. One week later they were auditioning for the Louisiana Hayride, with the same results. Their clothes were so ragged and sloppy, someone at the Hayride wanted to know if they were comedians. Buzz obviously treasures this memory, and says they were just kids, it was all a big joke. But Buzz would not be allowed to be a kid for much longer; within five years it would no longer be a joke, but for real, and he would be challenged with incredible overnight success, hardly out of his teens and into his twenties, finding himself not only on the Hayride, but the Wheeling Jamboree, Boston’s Hayloft Jamboree, the Old Dominion Barn Dance, and with his own television show, the first daily country music show in Washington.

This quick road to success was due to the right time and place as well as Buzz’s talent and determination. Washington was ready for bluegrass, with legendary country music DJs like Connie B. Gay and Don Owens playing the music on the air. It was Don Owens who gave Buzz and Scotty and Jack their first radio show on WBMD in 1952, where Don had just moved from WEAM. He had heard their music at Watermelon Park and was immediately impressed, and wanted to promote them. Buzz recalls that Owens approached him after their performance, and said he didn’t really care for that “western swing music,” what was currently the popular form of country music, and he wanted to put on some real bluegrass shows. At that time, Buzz says, there was no bluegrass in Washington. Only Buzz, Scotty Stoneman, and Jack Clement were performing straight bluegrass, and they were very good at it. Don Owens snatched them up.

By 1953, Buzz’s band had a job playing a Carmody Hills club called the Campus, a rough cycle club, where they made good money, around one hundred dollars a week each. But Scotty and Buzz were underage, so the manager said he had to keep Jack Clements and let the others go. Since Buzz was now married and had a child on the way, the club owner let them stay until they could find another job. Buzz had met Mac Wiseman through Don Owens, who had earlier offered him a job with his band. Buzz and Scotty drove to a bar at 14th and Florida Ave., where Mac was performing, hoping the offer was still good. Mac immediately asked Buzz to go to work for him, but Buzz said he had to hire Scotty too. He and Scotty had a deal that the two of them must be hired together wherever they went. Mac agreed, gave notice to Jim Williams (mandolinist) and Chubby Collier (fiddler). Then Buzz and Scotty joined Mac with Wayne Brown on banjo.

There was no bass in Mac’s new band; just the four of them performed. Mac was becoming quite popular at this time, with his recent release of “Goin’ Like Wildfire” on the charts, but Buzz never got onto any of the Dot recording sessions that went on during his six- month stay with Mac. He explains that the studio would only send Mac one ticket to Nashville, and Mac would just take Wayne with him. At this time, they were doing the daily Johnny’s Used Car show in Baltimore for $250 week. Mac and Wayne lived in Baltimore, but Buzz and Scotty stayed in Washington, taking the bus to Baltimore everyday on a commuter’s ticket.

Buzz went on to the Old Dominion Barn Dance in Richmond as part of Mac’s band. He sang tenor, with some lead on chorus, with Mac featuring him as a solo singer at least once on every show. Buzz says that he was Mac’s “main man. He was trying to push me up and get me on records. I was a real clean-cut person at the time and Mac trusted me. I was like his manager, handling the money, and the band.”

They traveled in a green ’49 Chevy at first, then Mac bought a new Ford Station wagon. In addition to being regulars on the Barn Dance, they played schools, parks, auditoriums, drive-ins and “nice clubs.” Buzz remembers that Mac would not work bars, only nice places. He also remembers a joke from this time that Mac would tell on him: at the drive-ins, the only way the audience had of applauding after every number or a hot break was to honk their horns. Once, after Buzz did a few snappy mandolin licks, a guy’s horn stuck, and Buzz kept taking bows, thinking the fellow kept blowing his horn because he was very impressed with him.

Buzz quit playing for Mac when his wife was pregnant again and didn’t want him on the road. However, Mac and Buzz remained good friends and Buzz still backs him up now and then even today for a show. Scotty had already left, going back to play with his family, and Buzz looked him up along with their old friend Jack Clement, hoping the trio could find some work making more money close to home. But at this time, Scotty was mad at Buzz for some forgotten reason, and Buzz was mad at Scotty. He laughs about how he and Jack and Scotty used to come together and go apart, “like kids. We were just kids squabbling with each other.” Buzz and Jack decided they wouldn’t hire Scotty, but Scotty ended up playing with them now and then just for fun, for free.

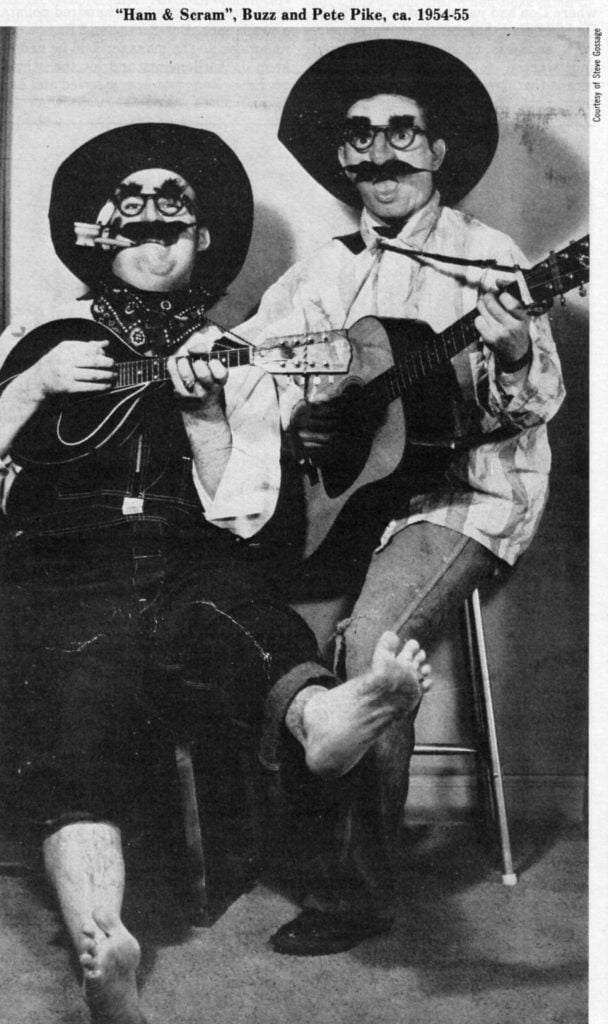

During this time, the never-say-die trio drifted into playing electrified music in D.C. area clubs and southern Maryland, what Buzz calls “hopped up” music, a kind of barroom jazz, because it paid well in clubs. Jack played some sax and Dobro and steel guitar, and Buzz put a pick-up on his mandolin. They would do their show entirely unrehearsed, completely spontaneous: “We were clever and could think fast. We jumped around and acted up, making up jokes on the spot.” They tried a little of everything, even classical. Jack could imitate any instrument on his guitar, and Buzz could imitate any instrument on his mandolin. “People would think there was a steel or a Dobro on stage. They thought it was fantastic.” Although Buzz says they didn’t particularly want to or like playing this music, they were only doing what paid, the seeds of the future popular “Ham and Scram” comedy act were being sown, with Buzz gaining experience in crowd-pleasing, clowning, timing and improvising, while he jammed and explored other kinds of music with Jack and Scotty.

In 1953, armed with a few songs Jack had written, and a Homer and Jethro type routine that they called “Ham and Scram,” Jack and Buzz auditioned for the Wheeling Jamboree, where they were hired, staying for about six months. Here, they linked up with Aubrey Mayhugh, who booked Hawkshaw Hawkins. He liked their act and the way they dressed. Jack wore bright red pants and a red bow tie with a white shirt, while Buzz wore a blue tie and blue pants and a white shirt. Mayhugh also liked Buzz’s falsetto laugh. At the end of each Ham and Scram routine, Buzz would say, “Folks, I’d like to leave you with a little laugh,” then break out into a high-pitched wicked laugh that broke everyone up. Mayhugh hired Jack and Buzz to go on tour with Hawkshaw Hawkins. They traveled with the Hawkshaw Hawkins show, backing him up as well as doing their own duet act, for about four or five months, while they were still at Wheeling.

When Aubrey Mayhugh went to Boston to be artistic director on the WCOP Hayloft Jamboree, Buzz and Jack went with him. Scotty joined them there for a short time. In Boston, Buzz got on the Mutual network for six days a week, broadcast from New York. These shows were taped at WARE, in Worcester, Massachusetts. Buzz was writing and performing his own songs by this time, and he cut his first record at WCOP, as part of a collection of Hayloft Jamboree artists, on the Sheraton label. The cut was “Cold and Windy Night,” with Jack Clement, Scotty Stoneman, and Ralph Jones on Dobro, and a staff bass player.

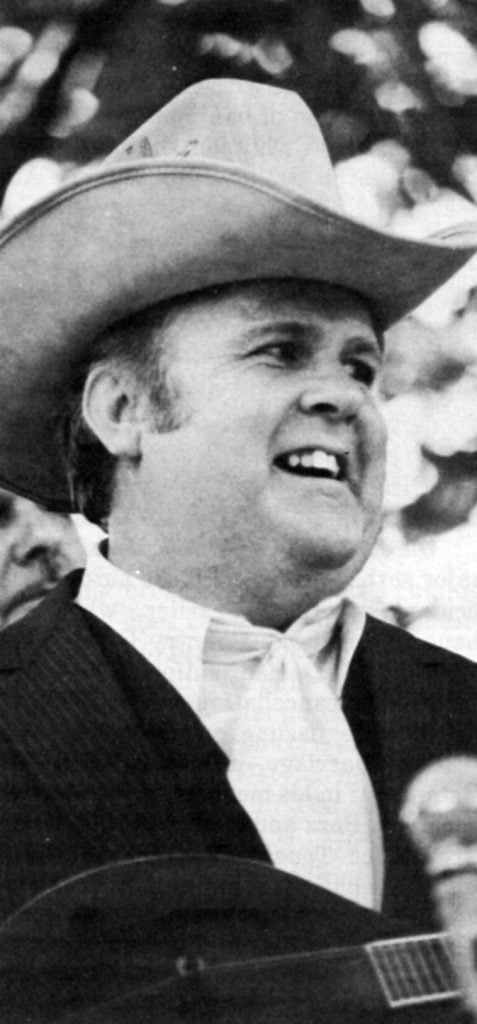

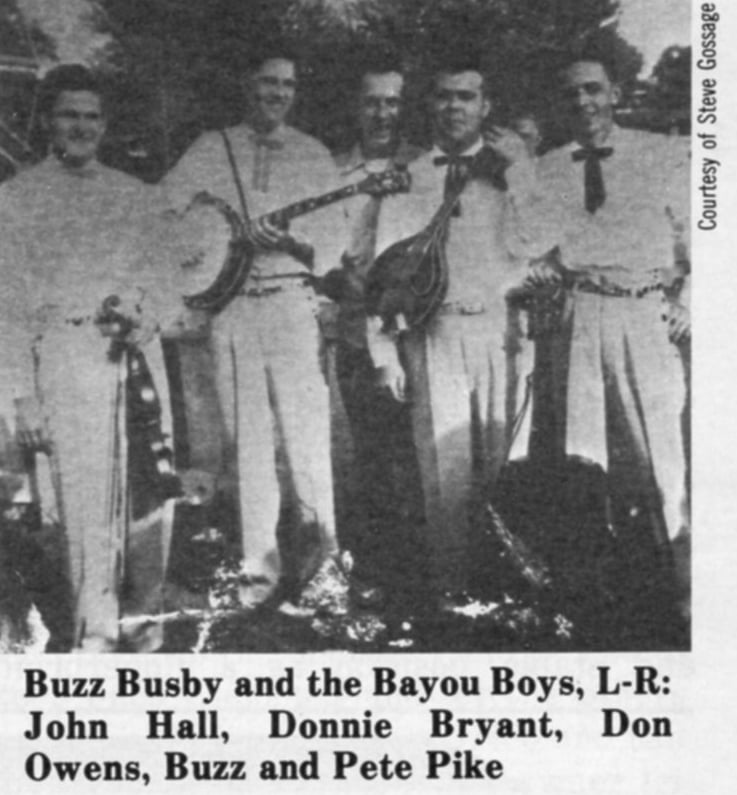

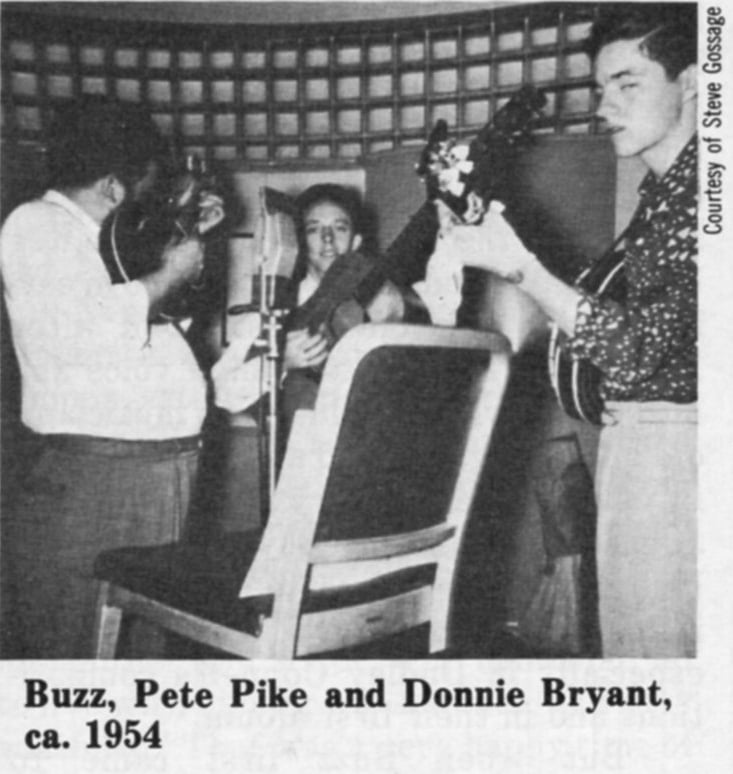

Buzz was beginning to have problems with his marriage at this time, understandably due to their long separations. Although his wife did not live with him in Wheeling, she came to Boston to live while he was at WCOP. But she returned home to Washington, and Buzz soon followed her. The Clement-Busby team was splitting up, with Jack wanting to try a single act. Buzz and Ralph Jones found a guitar player in Boston and went on the Hillbilly Ranch for a short time with Everett Lilly and Don Stover before Buzz went back to Washington, discouraged over the lack of work and deep snow in Boston. In Washington, he found a replacement for “Scram” (Buzz was “Ham”) as well as guitar player and lead singer in Pete Pike, who he had known since his FBI days, three years earlier, when Pete played with Smitty Irvin at a club in Washington. Buzz went to see Pete and tried singing with him and they liked the way it sounded. Pete and Buzz got together with Smitty Irvin’s father, Curley, who played bass, and they landed a job at a club called the Pine Tavern on 6th and Massachusetts Ave. for $95 a week. “We produced a hell of a lot of good music for just two people,” Buzz says about the early days with Pete Pike. Later, they added Don Bryant on banjo, John Hall on fiddle, and Lee Cole on bass, thus forming the band that would get them one of the first Washington, D.C. country music television shows.

The TV show came about, once again, as an indirect result of Buzz’s fierce drive to win. The band had walked away with prizes in almost every category at the 1954 Warrenton, Virginia National Country Music Championship Competition, with Buzz winning second place as vocalist. As a lucky coincidence, some programmers from WRC-TV in Washington at this exact time were looking for a bluegrass or country band to start a show similar to the Midwestern Hayride, a country music TV show in the midwest which was getting very high ratings. The WRC people wanted to try a regular live country music show in D.C. and happened to pick up a newspaper the day after the contest in Warrenton and saw a band there had won prizes in every category. The executives tracked down Buzz’s band at the Pine Tavern, the only place they could reach them since the band did not have a phone or a manager. Lee Cole, the bass player, answered the phone at the club, then told the exciting news to the rest of the band. But of course, no one believed him because Lee was always pulling tricks on them. And who would believe such a story anyway, that a TV station was calling them to do a show? Especially since a daily country music TV show was unheard of in Washington at this time. There had only been a few specials, such as the DAR Constitution Hall Stoneman Family concerts put on the air by Connie B. Gay.

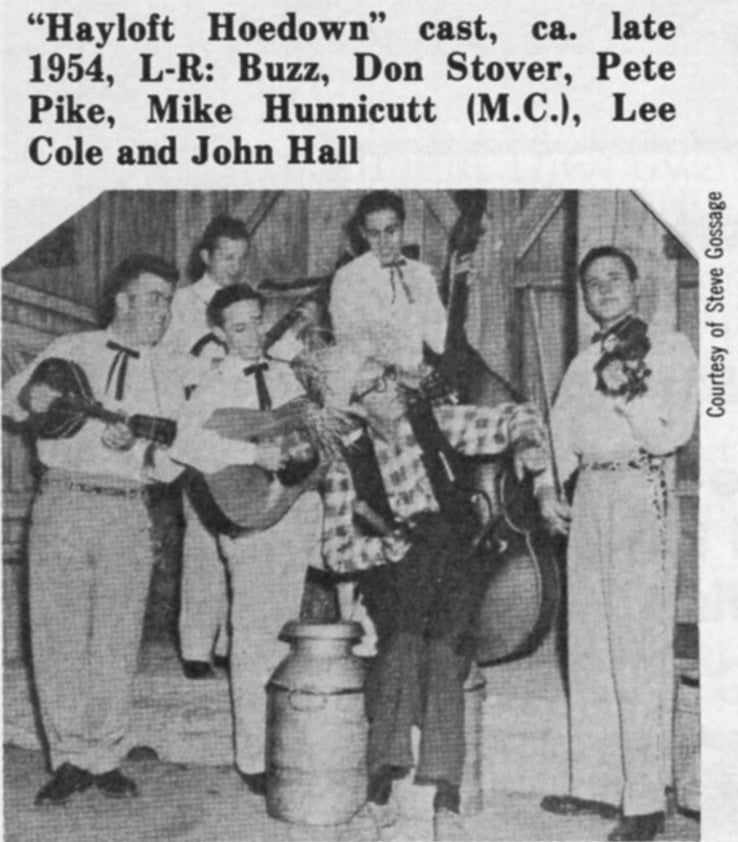

But soon, the unbelievable fairy tale story became true, and Buzz Busby and the Bayou Boys (as they were calling themselves now) went on the air with the Hayloft Hoedown in September of 1954. The show was on everyday in the afternoon for a half hour. The band at this time consisted of Pete Pike on guitar, Buzz on mandolin, John Hall on fiddle, Don Stover on banjo, Lee Cole on bass, with Buck Austin eventually taking Lee’s place. Buzz recalls the Ham and Scram routines were a big hit on TV, and he describes their comedy songs, like “Lady Insane,” and their skits with pride. He says the show was “fantastically produced” by Carl Dagan, comedian Bob Hope’s producer, and credits Dagan for making the show an enormous hit, especially with children, due to his knowledge of camera tricks and live TV skills. For example, the show would open with a double exposure technique to make Buzz and Pete look like tiny people inside a mailbox. Dagan put the mailbox in front of an all black background so there would be no size comparisons, then had the MC, Mike Hunnicutt walk up to the mailbox to gather the mail. The mail was jerked back into the box by rubber bands, followed by Ham’s (Buzz Busby’s) high falsetto laugh from inside the mailbox. Then Ham and Scram walked out onto the mailbox lid shaking their fists at Hunnicutt, before breaking into their Ham and Scram tunes.

The show was an enormous hit not only because of the Ham and Scram routines and Dagan’s expert production; it was the bluegrass music that was “really skyrocketing,” at this time, according to Buzz. “Bluegrass was just starting to take off, really get popular, and we were playing all bluegrass. The reason it skyrocketed was TV. TV exposed all kinds of people to bluegrass. Until then, only country music people had heard it. And they were all fascinated by it, because bluegrass is good watchin’ music.”

The band rehearsed for two hours before every show. An indication of the daily show’s popularity was the one hundred letters received every day. However, the program was only on the air for six months. The way Buzz remembers it, the show ended with disputs over who would get the most money —the MC (Mike Hunnicut), Buzz, or Pete. (Buzz and Pete were also having some disagreements at this time, on the verge of splitting up). In addition, the show’s producers were having problems with keeping sponsors who weren’t convinced the show was a success, even though the response was doubling. The producers actually took the large amount of mail up to New York to show the main office physical proof that the “hillbillies” were a hit. Although their first contract was for only thirteen weeks, the show was so popular it was renewed for another thirteen weeks, but when it came time for a third renewal, the show was cancelled and the band was given two weeks notice.

During the six months of Buzz’s TV show, he was enjoying incredible popularity in Washington. The band continued to play clubs, and people would come from miles around to hear them. They were also featured on the radio at WGAY, and went to the Wheeling Jamboree on occasional Saturday nights. Buzz remembers that people would stand in line for two to three blocks wherever they were playing during this time. “Everywhere we went people knew us. We would go in a restaurant and wouldn’t get charged for our meals. I’d be walking down the street and a cop would recognize me and pick me up and give me a ride.” In addition to being a local celebrity, Buzz was also making more money than he ever had in his life. He thought nothing of hopping in a cab to travel from Washington to Front Royal, Virginia [a distance of some 70 miles] because money seemed unlimited.

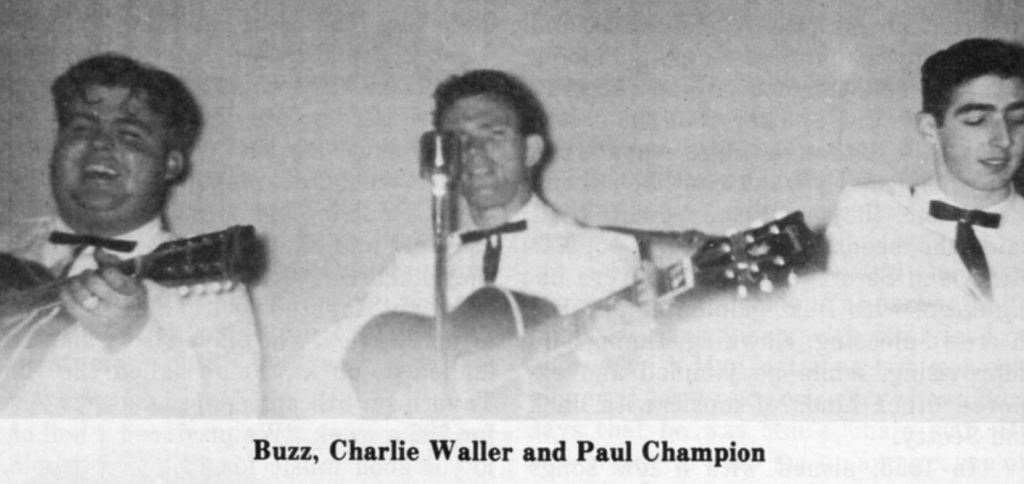

When the TV show ended in March of 1955, Pete and Buzz split up, and Buzz hired Charlie Waller for a replacement. At the time, Charlie was in Baltimore working with Earl Taylor at the Cozy Inn, but he left to be a member of the Bayou Boys, and stayed on and off until 1957, when the Country Gentlemen formed. It was Buzz who got Bill Emerson and Charlie Waller together, two of the original Country Gentlemen members, and, actually, it was due to an automobile accident Buzz was in that the Country Gentlemen was born. Bill Emerson was playing banjo with Buzz at the time, in 1957, when Buzz was in the accident. To keep the date, Bill called up Charlie Waller, who he had met through playing with Buzz, and John Duffey, who was a neighbor, and the Country Gentlemen group began that night.

But before this unfortunate accident that was to start the series of downslides in Buzz’s career, the Bayou Boys continued to prosper, with Charlie Waller taking the part of “Scram” and doing the lead singing and guitar playing for the group. They played clubs and radio shows like WINX in Rockville, Maryland, where Buzz was also a DJ for a few months, and got on the WRVA Old Dominion Barndance for five weeks, then finally landed on the Louisiana Hayride in 1955. The band simply drove down to Shreveport, with Bill Harrell, a good friend just along for the ride and gave the officials there a demo tape. This time their music was so professional, they were not laughed at or thought comedians; they were immediately hired. The group still consisted of Buzz, Charlie Waller, Don Stover and Lee Cole, with Vance Truell later replacing him on bass, and John Hall on fiddle, although a staff fiddler, Dobber Johnson, was used for the Hayride shows.

They stayed on the Hayride for nine months, touring as well during this time with package shows, appearing with various country and bluegrass artists like George Jones, Jean Shepherd, Skeeter Davis, Bill Harrell, Luke Gordon, and Reno and Smiley. The Hayride clearly tops the long list of prestigious shows Buzz has been on. He readily says it was his favorite, and points out that the Hayride was rated second only to the Opry in Billboard magazine at the time. In fact, Buzz claims country music fans during the Hayride’s peak used to refer to the Grand Ole Opry as the “Tennessee branch of the Hayride.” Buzz was fortunate to be on the show at this time, during its peak of popularity, sharing equal billing with such stars as Elvis Presley, Johnny Horton, Jimmy C. Newman, the Browns, George Jones and Carl Perkins.

It was during the Hayride that Buzz’s lifetime friendship with George Jones began. He toured with the George Jones show often then, and still does shows with him today. “At the time we both drank heavy and got to be good friends by seeing if we could outdrink each other,” Buzz remembers, laughing. Buzz fondly recalls the Ham and Scram routines with Charlie Waller during this time, remembering vividly one night on tour in a Louisiana school auditorium, when Charlie did his usual Hank Snow imitation to cover for Buzz while he was off stage “looking for Ham and Scram” (and changing into his Ham costume). When Buzz came back on stage as “Ham,” Charlie announced he would go look for “Scram” (and also change into his costume). So far, everything was going according to their worked out routine. But when Charlie returned to the stage he had two noses. He had hurriedly put his false nose on crooked, and his real nose was showing next to it, unknown to Charlie. Buzz just stared and busted out laughing because Charlie looked so ridiculous. He had to tell him his mistake, and Charlie fumbled, trying to straighten the nose, while Buzz tried to continue with the act so the audience wouldn’t notice. Then the whole mask fell onto the floor and Charlie picked it up and put it on, still not getting it right, and it fell on the floor again. By this time the audience has noticed so Buzz quickly makes the mistake into a joke, saying to Charlie, “Would you please refrain from losing your face!” The audience roared.

During the Hayride stay, Buzz began cutting records in earnest, with his first 45 coming out on a Louisiana label called Jiffy. The song was his now legendary “Just Me And The Jukebox,” a number chosen recently to be included in the Time-Life Honky-Tonkin’ record collection, the only straight bluegrass number among 40 honky-tonk country classics by such great artists as Lefty Frizzell, Ray Price, and Ernest Tubb.

By this time in Buzz’s life, although only twenty- three, he knew sharply the lonely life of honky-tonks. He not only played them, he lived them, and knew the soothing effects of good times, loud music, and drinking: “There’s people all around me, the nightlife is so gay” the song begins, then goes on to describe in vivid concrete images what it feels like to sit in an atmosphere of wild gaiety, passing lonely time, trying to kill painful memories, with only the music understanding, an only friend —“A glass of wine to ease my mind, since we’ve been apart/Just me and the jukebox, who knows my broken heart.” Buzz’s chilling high voice does not ache with loneliness, in the style of other honky-tonk singers, but is driven by loneliness, pain-filled and desperate in fast-paced bluegrass style. The song is hard-core bluegrass in instrumentation and style, not country or honky-tonk at all. The subject is honky-tonk. And it is this unusual combination—hard-driving, energetic, passionate bluegrass with images of the slipped-down honky-tonk lifestyle—that captures the essence of an incredibly lonesome existence, probably more lonely than the log cabin-mountain home lifestyle that came before it. Very few artists from any musical field have so successfully joined bluegrass with the spirit of honky-tonk.

“Just Me And The Jukebox,” surprised Buzz when it became such a hit. He really liked the flip side better, “Lost,” written with his bass player Lee Cole, another haunting, hair-raising song about sharply felt loneliness, with fast, driving verses followed by slow, moaning choruses. Buzz says he spent more time on this song than any he has written—an entire day instead of his usual 15-20 minutes of ripping out a song. He got bogged down so Buzz went to Lee Cole and played the chords for him, singing what he had so far. Lee liked it so much, he “infected” Buzz with his enthusiasm, and they finished it right there. The next day they got the band together and went into the studio and recorded it. When Jiffy had the tape sent down to Louisiana to be included with “Me And The Jukebox” on Buzz’s first 45, they really meant for “Lost” to be the main side. Buzz thinks “Jukebox” was more commercial country, and that’s why it became so popular.

Bluegrass was extremely popular on the Hayride, and the Bayou Boys were the only bluegrass band on the show. They got as many encores as Johnny Cash and all the regulars. He remembers Elvis as being a nice guy, who was “very clean-cut back then. I never seen him take a drink or drugs. Although it was rumored that he took amphetamines. I never said a word, couldn’t believe it.” But Buzz knows it could have been true from his own experience: “When you travel all night from one show to the next, three hundred miles, when you get to that next show you’re pretty tired. You don’t feel like gettin’ up and doin’ nothing. At that period in my life everyone I knew was taking amphetamines. I wouldn’t advise nobody now to do that. It’s hard on your health. But then, I didn’t know better. I was from the country. I didn’t know you could burn yourself out. I never heard of nothin’ like that. I’d go two to three nights without a wink of sleep and have to have a few drinks to go in and perform.”

Buzz recalls that Elvis liked bluegrass gospel, and was very friendly to Buzz and his band. Elvis used to get together just for fun with the Bayou Boys, and sing numbers like “The Wicked Path of Sin” with them, taking the lead and sometimes tenor part. His bass player, Bill Black, also used to hang around the Bayou Boys a lot, liking bluegrass better than what he was doing with Elvis, and he would constantly ask if he could come out and play bass on stage with them one night. Buzz never let him, because, “he wasn’t as good as Lee.”

When Elvis’s fame skyrocketed overnight, he left the Hayride, and the Hayride’s popularity fell off. Buzz began to think about leaving, because he could see the crowds growing sparse, with rockabilly coming into style. It seemed to Buzz that the Hayride was folding, and he was anxious to try somewhere new. He was shocked that Elvis’ music was catching on, when he had thought Elvis would be just a “flash in the pan.” In addition, his wife, who had been living with him in Louisiana, had left him once again to go home to Washington, so he went back to be with her. The manager of the Hayride begged him to stay, wanting to continue with bluegrass on the show, and liking Buzz’s high singing, but Buzz wanted to go back home. Jimmy Martin then became the bluegrass segment of the Hayride, taking the Bayou Boys’ place, and the Hayride did finally close two years later, like many other live bluegrass and country shows, a victim of the changing times.

Back in Washington once again, Buzz found few jobs in the summer of 1956. Finally, WARL gave the band a regular show, five days a week, for $450 a week. Buzz stayed at the station on and off until 1958. During this time, Buzz Busby and the Bayou Boys stayed busy playing places like New River Ranch and Sunset Park, as well as carnivals, schools, clubs and theatres in the Washington and Baltimore area.

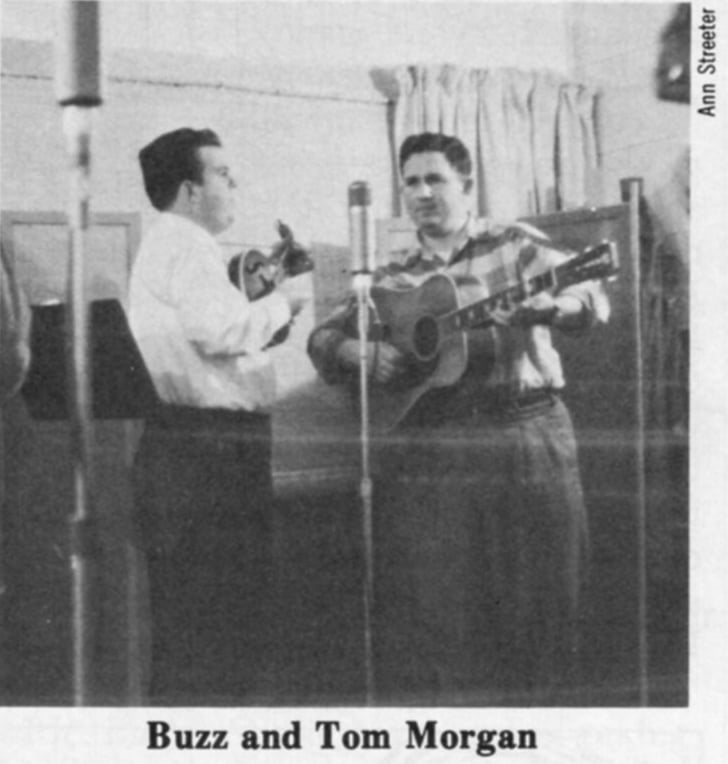

A recording contract with Starday came in 1957, with the help of Ben Adleman who recorded demo tapes for Buzz and his band and recorded much of the early bluegrass and country being played in the Washington area including Jimmy Dean, Roy Clark and Patsy Cline among others. The first Starday 45 was released in 1958, “Lonesome Road,” another spine-tingling vivid Busby original about the dead-end path he himself was already on: “Like a star lost in the sky, like a cold wind’s lonesome sigh, like the cry of a bird that’s lost its wing/I’m lost in darkness and sin, for I drink the devil’s gin/This lonesome road will never ever end.” Once again, Buzz showed his skill at writing songs with sparse, stark images dripping with loneliness, and singing them with a convincing, desperate high voice, a voice helplessly resigned to fate. Carl Nelson’s moaning, sighing fiddle backs up Buzz’s crying voice expertly, proving to be a good substitute for Scotty Stoneman who fiddled on “Lost” and was by this time busy with his family’s rising career as well as his own drinking problems. However, Scotty still managed to return to his old friend and play for fun at some of the Bayou Boy shows, and was in on one of the next cuts for Starday, “Lonesome Wind.” Pete Kuykendall also played fiddle some with the group. There was a succession of banjo players during this time: Paul Champion, Bill Blackburn, Porter Church, Smiley Hobbs, Eddie Adcock, and Bill Emerson all played with the Bayou Boys off and on during the late fifties. Vance Truell still played bass, and was on most of the Starday 45s. Tom Morgan replaced Charlie Waller on guitar for a while, then Pete Pike returned, staying until 1960. Bill Harrell replaced Pete, and recorded “Cold and Windy Night,” “Where Will This End,” and “Reno Bound,” all Starday 45 releases, singing lead.

On July fourth of 1957, Buzz’s first major setback came with the automobile accident mentioned earlier, which by chance formed the Country Gentlemen. Although Buzz had suffered setbacks before—the cancellation of his TV show, the Hayride fizzling out, and problems with his marriage —the accident seems to stand out in his memory as the point of no return. Buzz and Eddie Adcock, along with Vance Truell plus another friend had been bar-hopping at North Beach, Maryland, to celebrate the fourth, and hit a pole on the way home. “It liked to killed everyone of us,” Buzz says. He was pronounced dead at the hospital and was in a coma for a day and a half.

After over a month in the hospital, Buzz was on crutches and had to cut down on his performances, although he did go to the Warrenton, Virginia National Country Music Championship hobbling away with second prize again in vocals. Then he and Vance, who was also on crutches, went to stay with Vance’s family in North Carolina and recuperate. When he returned to Washington, needing money, he went to work for a bakery making deliveries until 1958. Although he still managed to play some club dates in North Beach, while holding down this job, he was depressed over not being able to play music full-time like he used to. The accident came at the worst possible time, just when rock and roll was making its popularity felt, squeezing out jobs for bluegrass musicians. A fellow on Buzz’s bakery route offered Buzz an electric guitar for $30, and Buzz thought, “Well, I can play a mandolin. I’ll just switch over to rock.” With his driven determination to succeed, in three months he had mastered electric lead guitar and, he remembers, was quite good at it.

Buzz got jobs playing lead guitar in rock bands in North Beach, Washington, and Virginia, teaming up with Pete Pike again. He also went to work at WKIK in Leonardtown, Maryland as a DJ, where he eventually became quite a popular personality in the area, due to his lively antics on the air. Between traveling to afternoon and evening jobs all over the Washington area, and working every day at WKIK, he “just lost too much sleep,” and driving home one night he wrecked his truck, totaling it, and landed in the hospital again.

After he got out, he went back to work at WKIK as a DJ and also got a regular job playing at a club in Leonardtown, staying there until 1961, playing rock, country and some bluegrass, still with Pete Pike. Between the DJ job, and the club, which paid well, he was making good money again, over two hundred dollars a week, and things looked brighter. However, Buzz’s health began to suffer as he continued to “pop those pills,” trying to keep his energy up, and he was in and out of the hospital with cardiac spasms, but nothing seemed to help. He went back to Greenbelt, Maryland to stay with his wife and rest, taking leave from his radio job.

When Buzz returned to his rooming house in Leonardtown where he had been living with Vance Truell, who, Buzz says, was “very wild,” he found out he had been kicked out of his room. It seems Vance was not supposed to be living there, and the landlord had found out and kicked them both out. Buzz simply found another room for them and got ready to go to his radio station job, but Vance was determined not to let the landlord get away with kicking them out. Buzz said, “Vance I’m on the air down here, I got to live with these people.” But Vance said, “I don’t,” and promptly stole a clock from the rooming house and took it with them. The landlord swore out a warrant for their arrest for petty larceny, and Buzz had his first trouble with the law. Buzz laughs about the incident now, remembering his wild days with Vance and Pete Pike fondly: “Me and him and Pete were good together, because we always had a rapport between us, and we always kept the crowd in stitches. Of course, we were all high, and we could think fast.” Vance eventually dropped out of Buzz’s life, when “his mother and father came up to visit and found him living a very sinful life,” and took him back home to North Carolina for good. “So we lost him. He never came back.”

In 1959, Buzz returned to D.C., and got a job playing the Harvard Grill on 14th and Harvard Streets, with a fiddle player named Paul Justis. From there, he went back to Southern Maryland, to Lexington Park, where he played clubs for over a year. In 1961, Buzz had his first serious trouble with the law, when he forged a prescription for amphetamines and wound up in prison, sentenced for three years. He was charged unjustly, Buzz feels with possession of narcotics, when he never received the amphetamines he wrote the prescription for. Buzz says bitterly of this experience, “I didn’t have a lawyer, and was very naive. I’d never been in jail before, didn’t know anything about it. They’ll never lock me up again, because I’ve studied law since then.” His older brother, Wayne, was now living in the Washington area and was a major in the service. In uniform, he went to the authorities and told them Buzz should not have been sentenced for three years simply for forgery. Wayne found Buzz had been made a scapegoat, because there was a lot of illegal drug use in the area at the time. Wayne bargained with the judge for his release by promising he would take Buzz back to Louisiana. In addition, Buzz used his pull with the governor of Louisiana, Jimmie Davis, who he had met during the Louisiana Hayride days, when Buzz’s band had backed him up on a show. He wrote Jimmie Davis asking for help, and Davis wrote Buzz a nice letter back, promising help, and asking him “to please be more careful in the future.” Davis then wrote the governor of Maryland on Buzz’s behalf, and Buzz was released in January 1962 after only six months in prison. Buzz was released on probation and on the condition that he go back to Louisiana for two years.

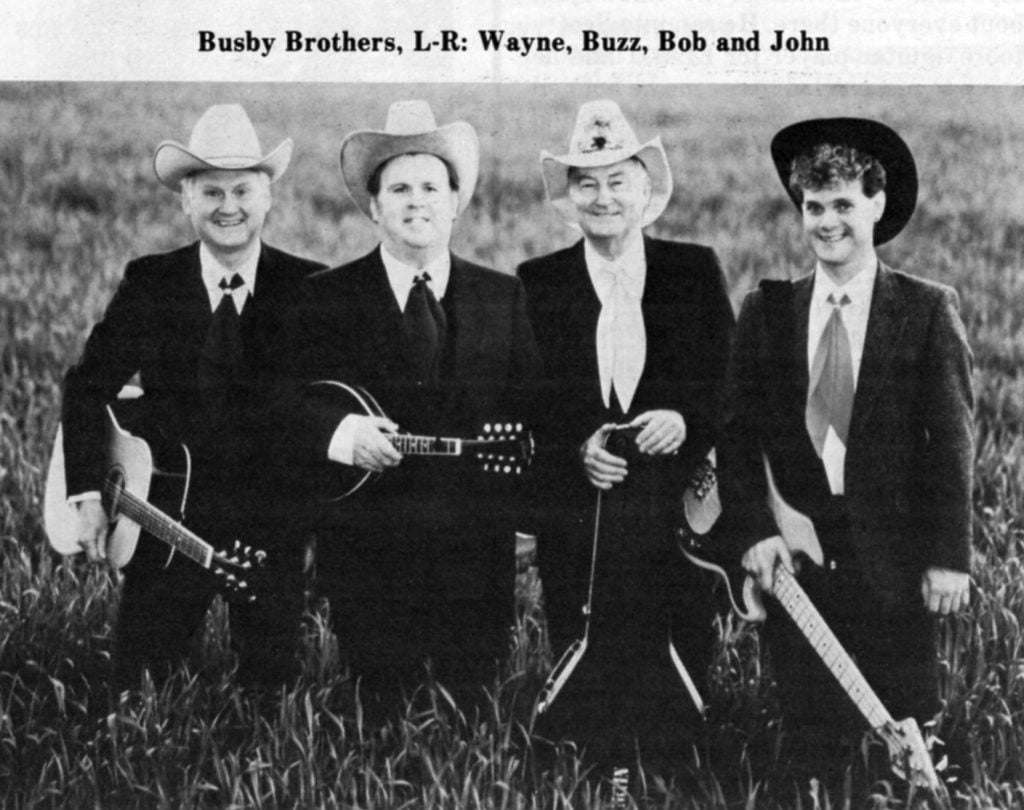

Buzz returned home, finding a job with the Twin City Jamboree in Monroe, Louisiana, where he stayed for two and a half years, playing his mandolin and occasional electric guitar, doing bluegrass and country, backed by a staff band. The Starday contract, which had kept Buzz busy recording from 1957 until 1960, was now over, and the only records Buzz cut during his Louisiana stay, were through is brother Waynes’ efforts. Wayne Busbice was now recording his own rockabilly songs in Ben Adleman’s studio in Takoma Park. He discovered Ben had a lot of Buzz’s old 1954 Ham and Scram material, and they released an album.

Ben Adelman also released a few 45s of Buzz’s when he returned to Washington, on the Almanac and Empire labels. Some of these 45s included Wayne, and were done in a variety of styles from rockabilly to Everly Brothers-style duets. Buzz was still writing new material, and had not lost his touch with heart-wrenching lyrics. In fact, his songs were more desperate and tragic than ever, as his life continued to become along many of the same lines. Buzz wrote, recorded and released “The Dream” at this time, (later recut on a WEBCO album), a recitation song that tells the story of the dreamer being tried by God and prosecuted by the devil who drags in every negative aspect of the accused man’s life. Then Jesus steps in as a character witness, testifying that the man has brought a lot of happiness to many people, pleading with God for a not guilty verdict, and saving the dreamer’s life. This haunting, sad tale was obviously deeply drawn from Busby’s own experiences at this time.

When Buzz returned to Washington in December, 1963, he struggled for a while, and then needing money, he went to work for Ben Adleman, who now had a record distributing business, putting record racks into convenience stores. “Ben thought I was a dumb country boy, and he thought he’d discourage me. So he put me to work getting racks in liquor stores, which are the hardest ones to get in.” Adleman didn’t know who he was fooling with. Once again, Buzz’s driving, compelling urge to win at anything he did surfaced: “I fooled him. I’d go out and in two or three hours I’d put five in. He paid me five dollars for each one, and I’d come back and claim my money and go to the nearest bar. Toward the last, I was putting eight in a day, and Ben said, ‘Jesus, Buzz, you’re breaking me, slow down. You’re taking all my records.’ I just did it to see how many I could get in a day.”

Buzz worked for Ben until 1965, not playing any music at all. He says he was an alcoholic during this time and didn’t know it. “It hadn’t really been a problem while I was in Louisiana, but I had become physically addicted by then. I’d go in in the morning shaking like a leaf, load up the truck, then as soon as I could get away from there, breathe a sigh of relief, and get a six pack.” Buzz and his wife had been divorced since 1961, and he was very much alone. Ben had to take Buzz off the record routes because Buzz was smashing up his trucks, and Buzz found himself now without an income. Buzz tried working for Music Time, a chain of music stores in the area, but he couldn’t handle the work, he was in such bad shape. He finally went to Spring Grove, a mental hospital, but felt like they didn’t help him much, and when he got out he was “very discouraged. I went to Takoma Park, and looked all around at this town, and really feeling sorry for myself, I thought, I’ve given a lot to this town, to these people, and nobody cares. I’m just leaving, the hell with it.”

His determination to make it resurging once again, Buzz decided right then to go to Nashville and get on a major label. He had a little money from a grant Spring Grove gives released patients, and he walked across the street to a Gulf Station and bought a late 1940s Pontiac for fifty-five dollars, putting on old Louisiana tags from a former car. But in Nashville, Buzz says, everybody gave him a sad story, saying things were rough in the business and they couldn’t help him, even though he knew just about everyone there. He ran into Scotty Moore, (guitar player for Elvis), “and he ran up to me, so glad to see me he hugged me. He was real nice and really wanted to help me,” but all he could do for Buzz was tell him Jack Clement was in town, and where his office was. “That made me feel good. I had a friend there. I went to Jack Clement’s. He was glad to see me, he always is. He locked his door and got his guitar out and we sat in his office and played music for an hour or two. He loves to play music with me.” Buzz admitted to Jack he didn’t have any money and didn’t know where his next money was coming from, and asked for help. “Jack promised me, ‘as long as you’re in Nashville, I’ll take care of you and help you, Buzz.’ ” Buzz thinks a lot of Jack for this, and will never forget it.

Another accident totaled Buzz’s fifty-five dollar Pontiac. This, along with not getting anywhere in the Nashville music scene, greatly discouraged Buzz. Jack told him his best bet was to go back to Washington or Baltimore and make a record there, let it make a big hit in a “town like that,” but that Buzz “had to do something on his own first,” before he could help him. Jack promised if Buzz would do this much for himself, Jack would take the record and make it a hit nationwide.

But Buzz tried once more to make it in Nashville, and got a job playing with Jimmy Martin. He played one show. Buzz then realized that playing with Jimmy Martin would not work out for him, because Martin was “too domineering,” although Buzz says, “he was nice to me, and decent, and took me to his house for two weeks to take care of me. He was really good to me.” In the depths of despair. Buzz called Martin’s house and said he couldn’t work for him and was leaving for Louisiana. Jack took Buzz to the bus station and paid his fare.

In Louisiana, Buzz stayed with his brother Billy and applied for unemployment. Buzz says by this time (1965), “the alcohol had me. I was very confused. I didn’t know what was wrong.” Eventually he left his brother’s for a hotel called the Robert E. Lee in Monroe, Louisiana. He spent his unemployment checks on booze and paying for this hotel room. He remembers the old man who owned the establishment as being good-hearted. He loaned Buzz money and looked after him, as well as the other down-and-outs there, buying one of his tenants a suit and trying to get him a job.

Buzz got occasional jobs in rough clubs in Monroe filling in for other band members. Eventually, Buzz wandered away from Monroe hitchhiking from town to town on the pretense of looking for a job, staying in Salvation Army missions. In late 1965, Buzz wound up in Little Rock, Arkansas, at Uncle Pearl’s Mission, because he found out you could stay at this place indefinitely (most missions had only allowed you to stay one or two days every six months.) Unable to get a job, Buzz began selling blood in order to pay for food, laundromats, haircuts, and of course, booze. He also picked up bottles along the streets when he was desperate for some money for a bottle of wine.

Finally, Buzz got a job in Little Rock driving a soft drink truck, but after three weeks he went on another binge and lost that job. However, his employer gave him three dollars and the name of someone with Alcoholics Anonymous. AA straightened Buzz out and he stayed sober for two years.

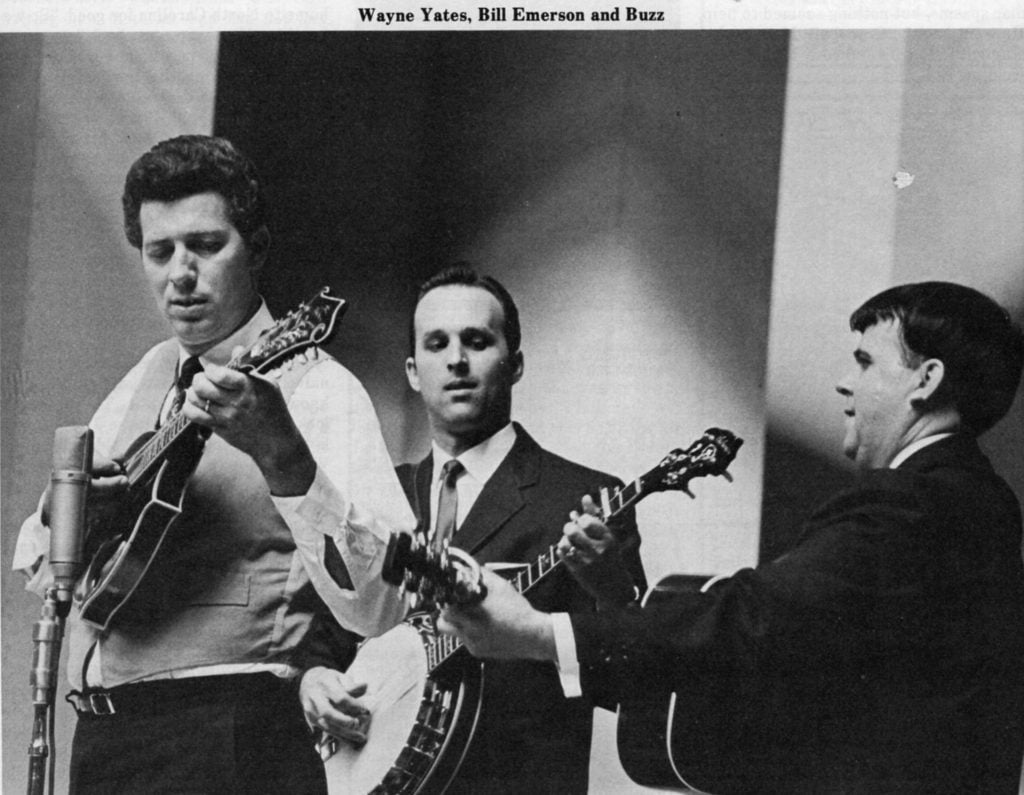

Buzz returned to Washington and went back to to work for Ben Adleman’s record business, then went into business with Dick Freeland, who owned Rebel records at the time, and Al Speakes, starting their own record distributing business. After a falling out with his partners, Buzz left, but got back into playing music. In 1966, Bill Harrell went with Don Reno, and Buzz got a job with what was formerly the Virginians —Don Stover, Buck Ryan and Stoney Edwards. Buzz stayed with them until 1967, playing Washington area clubs. Then he teamed up with Bill Emerson, Wayne Yates and Earl Brown. Patsy Stoneman then offered Buzz a job, and Buzz took it, forming a band with her and Don Stover, Ed Ferris, and his old buddy Scotty Stoneman. This band did not last long though, with Scotty’s severe alcohol problems, and Buzz’s problems returning. Eventually just Don Stover and Buzz were left, picking up what jobs they could, until 1968, when Buzz was arrested for assault with intent to kill, disorderly conduct, and hit and run.

Once again brother Wayne came to the rescue. Wayne knew the District Attorney and explained to him that Buzz was an alcoholic and needed to be back in Spring Grove, not in prison. The DA agreed to drop these serious charges if Buzz would go to Spring Grove. After his release from the hospital, which once again didn’t help his alcoholism much, Buzz took odd jobs, and didn’t play music. In late ’69, Buzz got with Bill Offenbacher and Clyde Thomas, playing clubs. “It got me back onto my feet again,” Buzz remembers. “I started buying nice clothes again and paying my rent.”

Leon Morris then teamed up with Buzz, and with a good band —Tom Gray on bass and Dick Drevo on banjo—Buzz was on his way to playing serious bluegrass again. Eventually Dick Drevo and Tom Gray were replaced with Ed Ferris and Lamar Grier. This band continued to play together into 1970, under the name of Buzz Busby and Leon Morris and the Bluegrass Associates, at a club called Ruby’s in Woodbridge, Virginia, four nights a week, as well as the Shamrock in D.C. now and then, and a few carnivals and festivals.

Leon and Buzz cut two 45s together: “Mule Skinner Blues” backed with “Warm, Red Wine,” on the World Artists label and “Just For Awhile” backed with an instrumental, “Scramble,” for Rebel Records. They also recorded two albums. One was later picked up by Rounder and released as “Honkytonk Bluegrass.” The other was put out by Leon under his name, after he and Buzz had parted.

Although things were looking much better for Buzz, with a band that sounded good, and cutting records again, Buzz couldn’t help comparing this to where he had been before, making nearly twice the money with his own television show and later the Hayride. “It’s hard to come down. It took me until 1976 to come down. I used to go out and spend a hundred dollars a day and think nothing of it.” The habits he had developed in the successful days, spending money freely and not saving it, and living fast and hard, were hard to break, and alcohol still had him.

On October 29, 1970, Buzz was accused of assaulting a policeman and went to jail again. He was tried and given four years for assault, which he felt was too much for simple assault. He and brother Wayne went to work once again, talking to authorities, and Buzz got out on appeal bond, then returned to serve a shortened sentence of four months in January of 1972. While out on appeal. Buzz went to Boston and worked with Don Stover, where he met the Rounder people and got the “Honkytonk Bluegrass” album released.

About prison, Buzz says, “It’s the worst downer you can think of. You’re life’s in danger every minute of the day. But I was choosy about who I would make friends with.” Buzz also got to play music while in prison, with a prison country music band called “Country Caravan,” a self-help group with sponsors outside that got the band jobs at fairs and carnivals in the area. He says it was a good band, with piano, electric guitar, drums, and bass, and excellent musicians. Buzz sang and played electric guitar with this group.

Buzz violated parole and was sent back to prison for seventeen months. Some of his time was served at a Southern Maryland Correctional Camp on work-release, where he was able to save up almost a thousand dollars by the time of his release in August, 1975. He then lived in College Park and tried to form a band with some “young kids” who were just getting started in bluegrass, but this fell apart when three of them went into the Army. Buzz went back to AA and quit drinking, got a steady job, and picked up work in music here and there with local bands over the next year and a half. Then, in the fall of 1977, he got together with a friend and went up to Boston to visit old places he used to play, like Hillbilly Ranch. Here, he got in a fight that put him in the hospital for over a month and left him blind in one eye. Once again, things started deteriorating and Buzz returned to College Park, drawing unemployment, and “really not doing anything, except laying around and watching TV.” He wasn’t playing music at all during this time, and seemed destined to become truly forgotten in bluegrass.

Then, in 1978, the Johnson Mountain Boys, who were just beginning to perform professionally, discovered Buzz. They had heard all of his old records and thought of him as a legend, and eagerly began playing with him on and off in clubs when they weren’t working their own dates. This got Buzz back into music. When the Johnson Mountain Boys went on to make a name for themselves and were unable to play with Buzz anymore, he continued to stay active in the local bluegrass scene, picking up jobs with area musicians like Lucky Saylor, playing clubs and events such as the Montgomery County Fair. From there, Buzz went to Jim Bowman and the Patuxent Valley Boys for about four months.

In 1979 one more accident, this time on a moped, put Buzz in the hospital with a broken leg. As with all his accidents and hard blows, he had a difficult time getting back on his feet again. But eventually he joined up with Al Jones and Frank Necessary and went on tour, plus cut a record album with them. After leaving this group, he formed his own group with Lamar Grier.

After all these years, Buzz still remembered his mother’s belief in the importance of education, and feeling that he had once again straightened himself out through AA, he enrolled in college in 1981, aiming to become an alcoholic counselor and help others. Although he did well in college, he also picked up two DWIs, which had now become a serious offense. With his record, he was afraid of going back to prison, and he skipped state. However, the effects of thirty years of hard living was catching up with him. He had diabetes, heart problems, high blood pressure, and a multitude of other chronic illnesses that forced him to come back home, disabled. He faced his charges and got fifteen days in prison. After serving this, he applied for social security benefits, and started receiving them in 1984.

Today, Buzz considers himself semiretired, and only plays special events or festivals now and then. However, he continues to write songs and makes records for WEBCO, the record company his brother, Wayne Busbice, started in 1981. On these recordings, although his voice is life-weary and broken, unable to hit those high harmonies anymore, it is still strong and powerful, like his mandolin playing, and most importantly, incredibly convincing. When Buzz sings about the tragedy of a life gone wrong, you know he has been down that road himself.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Nice story of a Bluegrass legend. But also sad.

any info about his choice of a Gibson A-50 instead of an F? It wasn’t unusual for some bluegrassers to play that model because they couldn’t afford an F-model, but later in their careers they were able to find an F. Did Buzz prefer the sound of that A-50 or was it a matter of cost? I’d also like to learn something about his use of alternate tunings. On a few recordings it sounds like he’s using that Get Up John tuning.