Home > Articles > The Archives > Bluegrass Music For Today—Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver

Bluegrass Music For Today—Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

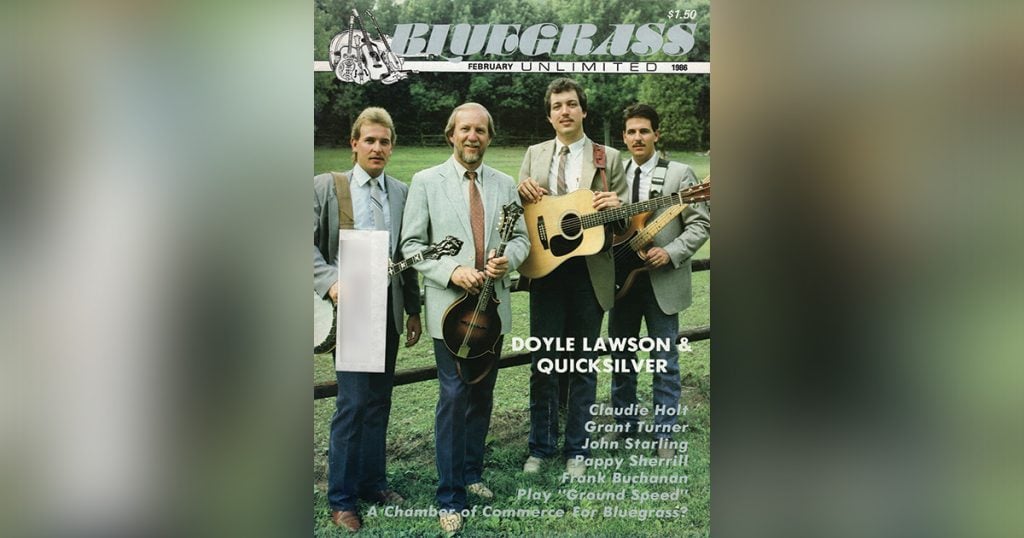

February 1986, Volume 20, Number 8

East Tennessee, the late 1950s, a boy just entering adolescence chops a borrowed mandolin, hoping to find the same licks he heard Bill Monroe play on the Opry the Saturday night before. The boy summons up the courage to wrap the mandolin in a cloth and head off across the fields to the next farm. Christmas has brought his neighbor’s brother-in-law home. He sees the smoke rising from the neighbor’s chimney and swallows hard. The key to his future, the route to the stage of the Grand Ole Opry and all that entails waits inside that farmhouse, for the neighbor’s brother-in-law is one of the best lead singers in bluegrass music, a man with records on the radio on the Decca label, a man called Jimmy Martin. He pauses a minute before stepping on the stoop. It’s a major step for someone who had wanted, ever since age five, to be Bill Monroe when he grew up.

“By this time I was fourteen years old and playing pretty decent, but I had trouble playing real fast,” Doyle Lawson recalls. “Jimmy set with me a long time and said, ‘You’ve got a good left hand, but you got a stiff wrist.’ So he showed me how to use my wrist properly and told me what to do to rehearse with it.” 1963 found Doyle playing banjo, in J.D. Crowe style, of course, with the Sunny Mountain Boys. “Working with Martin saved my timing for sure. That was the thing he stressed with me—timing, clarity in what you’re playing, definition, bringing out the strong notes where the people know what you’re playing, and you play a melody. Don’t play too much, just enough.”

Doyle left Martin after a few months, disillusioned with the life of a bluegrass sideman. “I was very young and totally unprepared for life on the road. Back in those days, we worked high schools, bars, store front congregations, anything people could get a hold of. You did radio shows. You drove all over the United States putting tours together, and you worked six days a week. After I’d gotten away from it, even the grind of being on the road as much as we were didn’t seem so bad compared to what I had to do then. In 1966 I became an official member of the J.D. Crowe band, which at that time was the Kentucky Mountain Boys. I stayed for about three years.”

Those were the days of playing the Lexington Holiday Inn, sometimes with Red Allen, and of Crowe’s first solo albums, which have been constantly reissued. With Crowe, Doyle began thinking about material seriously for the first time. “It was a do or die case. We were working the Holiday Inn five nights a week, and let’s face it—you can’t do the same 30 songs but for so long. We thought for the sake of survival we were going to have to be able to create an identity. We had to introduce songs that we wanted to do, that we felt was a good song. The people loved it because it was something different. It doesn’t matter where a song comes from. What matters is how you do it.”

In 1969 Doyle left Crowe, put in another stint with the Good ‘n’ Country man. as a mandolinist this time, and returned for two more years as J.D.’s guitar picker. Late in the 1971 festival season Bill Emerson arranged for Doyle to audition to replace Jimmy Gaudreau playing mandolin and singing tenor with the Country Gentlemen. “I had laryngitis real awful, but I tried out, and I guess what saved me was that I knew all the songs, and my tenor was sort of gutsy. We decided to give it a go. I liked it so well I was there seven and one half years.

“It was a good stay. I really enjoyed it, and they gave me the biggest shot I could have gotten as far as my career goes. I owe a lot to them ’cause they gave me a lot of freedom, a lot of room just to explore, and they were open to things that I brought in to try. It means a lot.”

With the Country Gentlemen, Doyle expanded his musical activities and developed new skills, including record production, for which he was never credited on their Rebel albums, and song selection and arrangement, a natural jump from Crowe days. “There’s not a better singer in bluegrass or any music as far as I’m concerned than Charlie Waller. So I would always listen for ‘Well, Charlie could really sing this song.’ Then I’d take it and do something to it to add to what he was doing as far as the harmony parts.”

While a Gentleman Doyle recorded his only solo album, “Tennessee Dreams,” for County Records in 1977, and did some session work for David Bromberg’s “Midnight On The Water” album and several of Mike Auldridge’s Dobro records. But the desire to front his own band burned brighter and brighter in Doyle Lawson’s mind.

“I felt that after that long I had fulfilled my purpose with the Country Gentlemen. I couldn’t see anything else I could give them, and they deserved more than that. I wanted to leave before I got to where I wasn’t productive at all musically. As far as friendship, I love them like brothers still.

“I wanted to try my own group because I felt I could make it work. I knew that if I didn’t do it, I’d always wish I’d tried. I always wanted to go in from the ground floor without having to walk in where somebody else had already been and you have to conform because there’s a style already set. I always had said I wanted to do something where we go in from the ground up, and you have these ideas in your head, but you don’t really know what’s going to happen. You figure out the sound you have, then you sort of follow what the people are buying. They hit on what they want to hear. If you’re a smart man you’ll listen to what the people want to hear.”

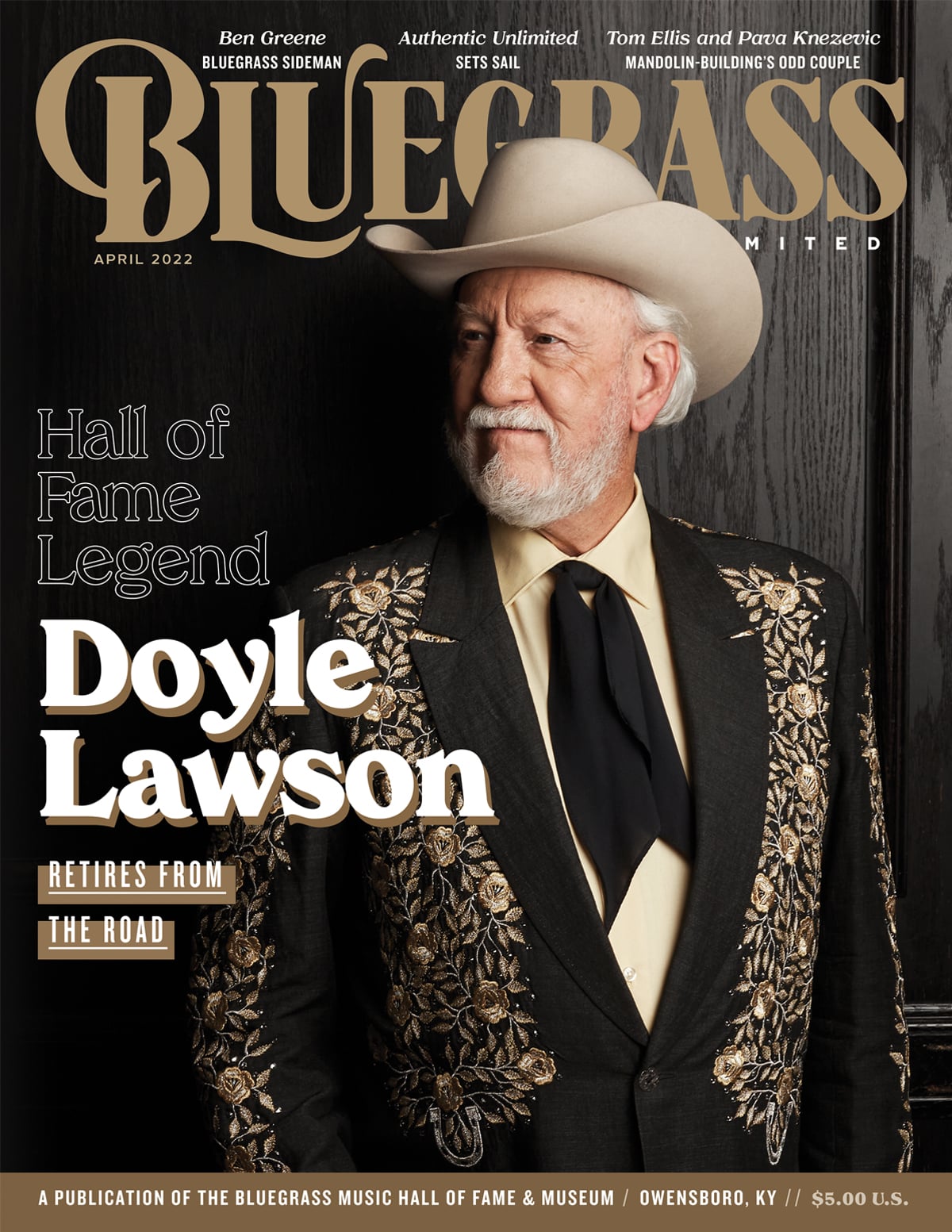

For the last few years what the people have wanted to hear has been Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver. A Linear Group survey of 2100 bluegrass festival fans last summer found their name listed under favorite band more than any other, including close runnerup Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys.

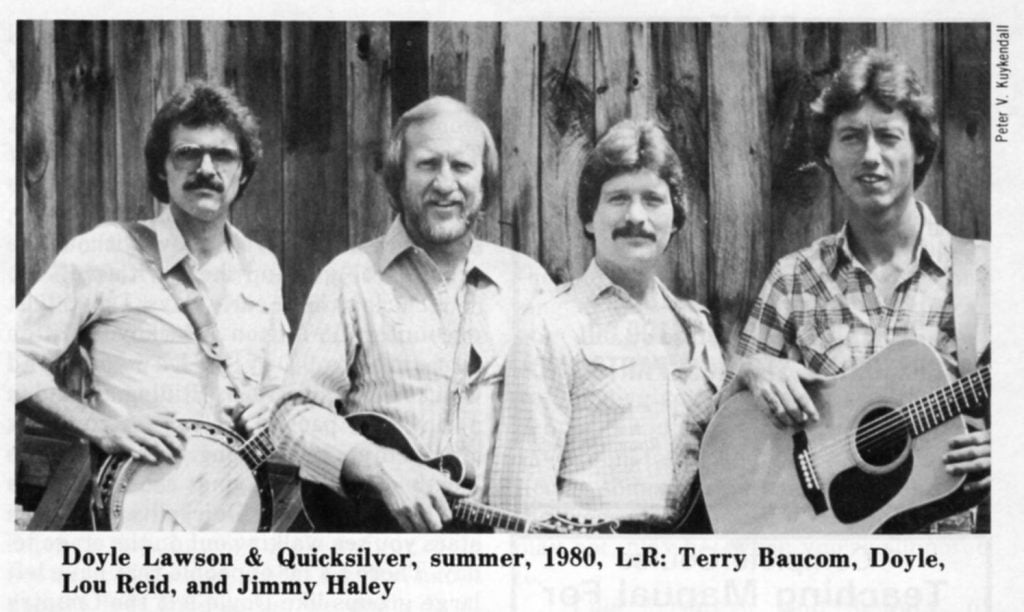

But when Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver officially formed on 2 April 1979, they were one more brand new bluegrass band just in time for the festival season. Putting together a band that would bring festival crowds to their feet turned out to be the easiest part of the task. “I made this one phone call essentially. That was to Jimmy, and all of a sudden he had these guys here that could do the job.

“The most important thing that you’ve got to have is a good rhythm guitar player. I thought and thought and couldn’t come up with anybody. I tried out some people, and it just didn’t work. Then on the way home I thought, ‘Jimmy Haley —he’s a guitar player.’ So I started trying to find him. I asked around and found he was in Greenville, South Carolina (playing with Southbound). I called Jimmy and told him what I was interested in and asked him, ‘Do you know of anybody that plays banjo, that’s looking for a job, that is good, and can sing?’ “He said, ‘Terry Baucom [then late of Boone Creek] is looking for a job. He’s working with us some now.’

“At that time they were not doing a whole lot with Southbound, so we contacted Terry. I said, ‘We need an electric bass player.’

“Terry said, ‘Louis [Reid, also of Southbound, now with Ricky Skaggs] plays an electric bass. That’s the first instrument he played.’

“So they drove up to Virginia, and we worked out one afternoon. They came back, and the second afternoon it just clicked.”

Then came the hard part, polishing a new group of four musicians that clicked together into a working team, a bluegrass band. “I said, ‘The first thing we’ve got to have is a vocal group. Everybody knows how well you can pick, but vocals sell records. Vocals win you fans.’ So we worked day and night. We worked 12, 14 hours a day, everyday, on singing. We’d get in a room, all separate in different directions, and come back to see if we were still together, on pitch and phrasing together. If it wasn’t right, we’d do it again. That’s a trick I learned from Earl Scruggs.

“So that’s how we got our vocals together. Plus when we got together for a rehearsal, we taped everything we did. We’d go back and tape it again, and tape, tape, tape until we got what we wanted. We did that about six weeks, then we hit the road.”

Doyle’s new band made their first public appearance at Buddy’s Barbecue in Knoxville, Tennessee on 9 May 1979. The next night, a Friday, found them at the Down Home in Johnson City. Doyle and company drove over the mountains to play two sets at the Pickens, South Carolina festival on Saturday afternoon, and then motored a 140 miles over twisting roads to headline the Down Home again on Saturday night.

They performed on that hectic weekend as Doyle Lawson and Foxfire. “We found out,” Doyle recalls, “that there’s about half a dozen groups floating around with the same name. I thought about Quicksilver. What we wanted was a name that was different, easy to say and easy to remember. We wanted something that when you said it, you could remember it.” And so Foxfire became Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver.

“My name is in front, but it’s not featuring me. We feature the total group. It’s structured so that everybody has a featured part. Everybody gets to work. Everybody gets to be heard. There’s not a man in this group who can’t sing at least two parts, maybe three. You don’t hear the Doyle Lawson show, because I don’t have a show without the other three guys up there with me.” During those early days, Doyle first encountered Milton Harkey. Milton remembers Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver circa 1979: ‘‘Riding around in a tiny van packed full of instruments, cramped up and driving from Florida to North Carolina paying their dues as Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver, not the stars you see walking out on the stage today. There’s a lot of people that have left large groups like Doyle left the Country Gentlemen, and hadn’t really cut it. But there was just something about this group. They were getting standing ovations in the middle of their sets. The energy Doyle and Quicksilver were putting out was unbelievable, and they weren’t as good then as they are now.”

“It was rough at first, but we knew it would be,” Doyle agrees. “You can’t imagine having already been playing fifteen years and you start over. The people know what you can do, but they want to hear what the group does. You’ve got to take two years to prove to the people you’re for real. I’ll tell you what I did as far as the financial end. I gave myself five years: if I can start over, and we can do what I was doing with the Gents in five years, I’ll be happy. Well, we’ve been blessed. We arrived in early 1983. The people have been really good to us. We’re working hard. We want to do good for the people. We want to be worthy of their respect and admiration.”

While Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver worked hard for the people, their efforts came back to them. For example, the ease with which they got on one of the top recording labels for our music, Sugar Hill. “Barry [Poss, Sugar Hill president. See BU Oct. 1982] knew I was going to put together a group that was worthy of being on his label… we made a tape. I played the tape for him over the telephone, and he said, ‘When you’re ready for the studio let me know.’ ”

Their first album, “Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver,” received a highly favorable response on its release in 1980. The big breakthrough, however, was the second album, “Rock My Soul.” Almost immediately it set the standard not just for Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver, but for gospel bluegrass as a whole. Listeners heard perhaps the top vocal quartet in any kind of music in their most favorable environment. All the now classic a cappella gospel trademarks were present on “Rock My Soul,” especially the signature style of three parts together and the fourth floating. The record returned bluegrass gospel to the mainstream of our music and gave Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver a legitimate standard in “On The Sea If Life.”

“I had no idea that our gospel music would be what it is today,” Doyle admits. “I think that since we got started with the quartet singing, the bluegrass gospel singing has done a complete turnabout for the better. Flatt & Scruggs always featured a lot of gospel singing, so has Monroe, but the newer groups never followed up with it.

“With the material that I’ve done, I’ve gotten away from doing a cover of what already had been done. Occasionally we’ll do a cover, but it won’t sound like you’ve heard it before. We rearrange it and restructure it. I had a lot of these songs that I grew up with. I bet there were a lot of people that had never heard these songs. I wondered if they would like them as much as I do. A lot of the stuff I did with the Gentlemen and with Quicksilver came from my daddy.”

So successful has Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver been with gospel that they’re able to play some dates as a gospel group. The music has also gone over quite well with foreign audiences, especially in the Near East. “They love gospel. They can relate to acoustic music because the bulk of their music is acoustic. The only difference is that they play and sing in quarter notes, and we sing and play in half notes.” Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver have made trips to the Near East, North Africa, and Europe. Country Gazette, the Dutch magazine, in 1983 named them the top bluegrass band and “Heavenly Treasures,” their fourth LP release, as album of the year.

“Heavenly Treasures” featured a new Quicksilver bassman, Randy Graham, an original Bluegrass Cardinal during his mandolin picking days. “Randy was the first fellow we thought of when Lou decided to leave because their vocal range and their abilities are pretty much the same. Terry somehow came up with Randy’s telephone number in Arizona, and I called him up. He said, ‘Well, you guys are the only group I’d even consider because I like to sing gospel. I’d like to do it.’ ”

They had become the quintessiential second generation bluegrass band, at the least as important in defining that style as the New South, the Seldom Scene, or the Johnson Mountain Boys. They stress vocal presentation and instrumental teamwork, rather than hot licks. They have developed their own approaches to carrying the values of first generation bluegrass into the 1980s.

“Our band plays bluegrass music with a today approach as opposed to a 1947 approach,” Doyle explains. “I cut my teeth on traditional bluegrass music when I grew up in east Tennessee. Mr. Monroe was my main influence. He was the reason I wanted to play bluegrass music. A lot of people may say if we don’t sing ‘Cabin In Caroline’ or ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky,’ we’re not playing bluegrass. That’s not right. You can’t relate it to a song; you’ve got to relate it to music in general.”

Doyle with a few well known friends has paid his respect to the old songs and the artists who created our music with the Bluegrass Album Band. “We go back and try to recreate things we listened to when we were serving our apprenticeship, but we recreate in our own way. It’s not the same. There’s never in the world a way that you could sound like Flatt & Scruggs or Monroe or any of those groups. What you can do is play the same music with the same idea, the same expression, to show that you went to that school. That’s the whole hook … out of five or six people, it’s all put together into one music.”

Now Doyle Lawson finds himself inspiring the work of a new, third, generation of bluegrass pickers. “I’m glad to see it. Kids today weren’t around when I was a kid, so they weren’t exposed to what I was. They’re trying to pick up on what we’re doing today. What it does is create another generation. We want the music to continue, and the only way for it to continue is for groups to be around like the Seldom Scene, the Bluegrass Cardinals, the Johnson Mountain Boys, and us. There’s a few groups that for one reason or another people like to stylize from. That’s encouraging, because as long as you have that you know this music’s going to go on… it’s a continuous cycle. You’ve got to have it.”

So what makes Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver so good? Having four great singers and tasteful pickers is a good start, but it takes even more than that. Let’s begin with song selection and arrangement. “I listen to the lyrics, how well it’s written, and the melody … you’ve got to have a melody that will touch the people. You’ve got to have something that you can express. I listen to that, how we could do it or could not do it. If it’s a song that we like, and it doesn’t feel good to us, we don’t do it. You’re best to leave it alone even though it’s a good song. All songs don’t work for everybody.

“Too many times too many people do covers of music that’s already been done when this market is not big enough to afford covers. If you want to hear ‘Rocky Top,’ play the Osborne Brothers. If you want to hear ‘Fox On The Run,’ play the Country Gentlemen. If you want to hear ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky,’ play Bill Monroe. If you want to hear ‘On The Sea Of Life,’ play Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver!”

Once Doyle selects a tune, arrangement becomes a team process. “When I get a song, I pretty much have a basic idea of what I want to hear. We’ll take that, and then one of the guys might say, ‘How would it sound here if we did it like this? We take a basic idea and work from there.”

Once they have some great songs how do they sell them to the people? “By being open and honest in our presentation. It’s there, and it’s us. It’s the way we feel about it. We’re saying please like us. We try to play what the people like to hear. The calibre of music they like to hear is what we try to do.

“This is our music as we want to present it,” Doyle continues. “We try not to sound like anybody else … we just try to do music that we hope people will like and try to pick songs we hope people will like. We try to catch their ears, to make them listen to us. If they don’t listen, they don’t come but to one show, because they don’t remember who you are.

“I’ve always felt that simplicity is the purest form of music. If you don’t sing or pick something that a guy can hum along with you, whistle, or sing two or three bars of it, then you aren’t there yet. You’ve got to play a music that the people can understand. All songs don’t have room for freedom, so keep it in particular songs where you know you have the freedom, then use it. If you want to play hot, play hot when you’re supposed to.”

The strength and beauty of bluegrass music has always come from the tension between old and new, and through focusing the musicians’ talent and creativity within the limits of the style. A band as powerful and ambitious as Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver wants to be heard by as many people as possible. The question arises, then: how far to go in order to sell records without losing the bluegrass sound. “What you want to try to do is expand the music to be a commercial kind of music without trying to sell out. There’s a stopping point. If you get past a certain point you’re not playing what they refer to as bluegrass music. You will be surprised at the number of people who will listen to your music if you present it right.

“You can do little things to get airplay that don’t take away from the music. We’re radical enough that I’m not above putting a steel guitar on a record if it’s played right. If a steel guitar’s played with the taste that Mike Auldridge has, I like it. We think it’s pretty, and I’ve found that usually when we think something’s pretty, the general public agrees with us.

“The only way to get airplay is to be different. Go for it. It may work and it may not . . . but you’ve created something. You’ve got a little bit more than you had before you tried it.

“In any kind of business, you have to have a goal at all times. The goal now is to continue. My feeling is that if we can do it in this amount of time, then there’s a lot more that can be done. So my goal is to press harder.”

Doyle has a special interest in record production and feels that poor production and low recording quality are two shortcomings that have hurt bluegrass music. Now Doyle has creative control of their records so he can make sure of the quality himself. He has also developed a strong working relationship with Bias Studios in northern Virginia and their crack engineer Bill McElroy.

Over the years Doyle has not only learned a great deal about production in general, but has become the world expert on how to manage his band in the studio. First off, he tries to avoid overdubbing so as to keep a live in the studio feel. “But there are ways to do that where you don’t lose the natural feeling. What we did on this album [1985’s “Once And For Always”] was we did some bad tracks first with a dummy vocal to keep that feel. Then you go back and do the vocals.

“Now the a cappellas, we cue it, and we run, and we don’t stop the tape to make sure we’re still on pitch. We do the whole thing all the way through so you get that spontaneous feeling for the song. The surprising thing was there were almost no overdubs to fix unless somebody’s voice cracked, and you’ve got to fix one word. So you go back, and you do one line. You take that word from that one line and put it with the other, and you’re home free.”

Doyle and the group worked on their fifth album for Sugar Hill, “Once And For Always,” during much of the spring and fall of 1984. “Basically it’s a Quicksilver album” Doyle says, “it’s a little bit different than the previous ones. It’s kind of a bluegrass/countryish-flavored type album … it’s more of a boy-girl record than we’ve done before. We don’t want every album to sound alike or to keep singing about the same subjects. We want to jump around do different things.”

Not so different that Doyle would neglect the fine a cappella gospel songs that the people love. “Once And For Always” includes two such offerings—“A Lover Of The Lord” and “When The Sun Of My Life Goes Down.” Fans gave both their highest approval ratings during the 1984 festival season with ovations rivaling “On The Sea Of Life.”

Different enough, however, that the festival faithful discovered an entirely new Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver in 1985. Not only had Doyle undergone a spiritual rebirth and abandoned alcohol and tobacco, he had recruited three new musicians for Quicksilver. After a final gig with Doyle at Smithfield, Virginia on 11 May, Terry, Randy, and Jimmy launched their own group with Alan Bibey on mandolin and vocals.

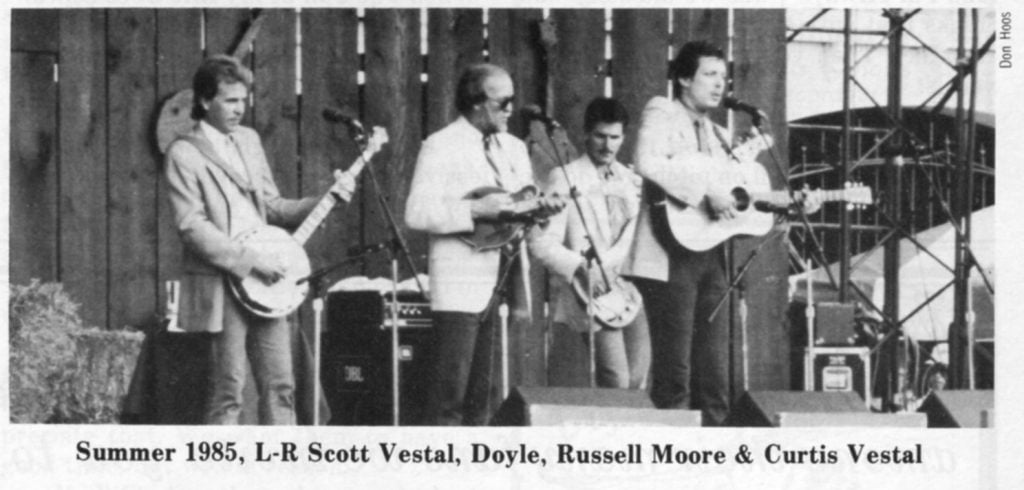

Doyle’s new backup band consists of Russell Moore from Pasadena, Texas on guitar and singing lead, and Arlington, Texas brothers Scott and Curtis Vestal on banjo and electric bass respectively. All three had been playing with Southern Connection, a highly acclaimed third generation bluegrass unit last based in Asheville, North Carolina.

After but two months with Doyle the threesome had grown comfortable with their new role when the Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver Family Style Bluegrass Festival took place in July. The crowd response suggested the fans had likewise accepted the replacements.

“We’ve had a good reception,” Russell allows, “it’s just that feeling of being watched.”

“And they really look at us hard,” Scott adds. “It seems like once they’ve heard us a little bit, they relax and start enjoying it instead of being critics.”

The opportunity to work with and learn from such a pro caused the trio to jump at the opportunity when Doyle called them in mid-April 1985. Three weeks of intense rehearsal immediately paid musical benefits.

“In the ‘Connection’ we were playing everything real fast,” Curtis notes. “Doyle’s taught us we don’t have to play so fast to have that drive.”

“It’s been work, but onstage is really dynamite,” according to Scott. “When we go onstage everybody’s feeling good, ready to do their best. Nobody’s mad at each other.”

“When we go up there we’re going to have a good time. It’s just a feeling of knowing that even at its worst it’s still going to be bearable to listen to,” adds Russell.

“It’s fun seeing Doyle up there having a good time,” Curtis confesses.

And Doyle seems quite pleased with the band so far. “I can’t praise them enough. They’re hard workers, and the results are phenomenal, better than I’d expected.”

The summer of ’85 saw the boys looking forward to their first recording project with Doyle, a gospel album on which work was slated to begin in the fall.

The Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver Family Style Bluegrass Festival held each July near Denton, North Carolina provides a great forum for Doyle’s band and second generation bluegrass in general. Like all of Doyle’s projects, the festival’s high standards set bluegrass trends, healthy trends, although he and Milton Harkey, the Asheville, N.C.-based promoter, only initiated the event in 1981. “A few years ago, festivals were getting to the point that they were getting somewhat out of hand,” Doyle explains. “I thought if we don’t do something about it, I’m going to suffer. My livelihood is playing music, and if I don’t have a place to play them I’m out of business. So I had to do some little something to turn that around and get the people back to where they respect the music.

“A lot of festivals have started to turn around also to the family style, and making stipulations, rules, regulations, and requests. I’ve noticed a big change in the last couple of years. I hope we’ve had a little input because the idea we had was solely for the preservation of our kind of music.”

Again, the Doyle Lawson formula is good common sense: “The people respect us because we respect them, and they appreciate that. We want them to have a good time, but within reason.”

It all fits together when you look at Doyle Lawson’s career in festivals, records, and on stage. Every time you can find careful planning, meticulous execution, honesty, consistently high quality, and, most important of all, enough respect for his audience that Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver always gives the best they have to offer their fans. “We want an image of being professional and humble—don’t be above the people who pay your ticket. One thing our band always tries to do is to project energy. I’ve got to confess that there are sometimes when there’s just not a lot of energy left, and you do the best you can. People say we’re pretty consistent, but we’ve never lost the desire to go out and burn it. Entertaining those people and playing music to them, that’s what we want to do. We never lose sight of that fact.”

As long as they keep that simple fact in mind, Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver can only get better and better.