Home > Articles > The Archives > Bluegrass Mandolin—1/3rd Century Later

Bluegrass Mandolin—1/3rd Century Later

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

March 1972, Volume 6, Number 9

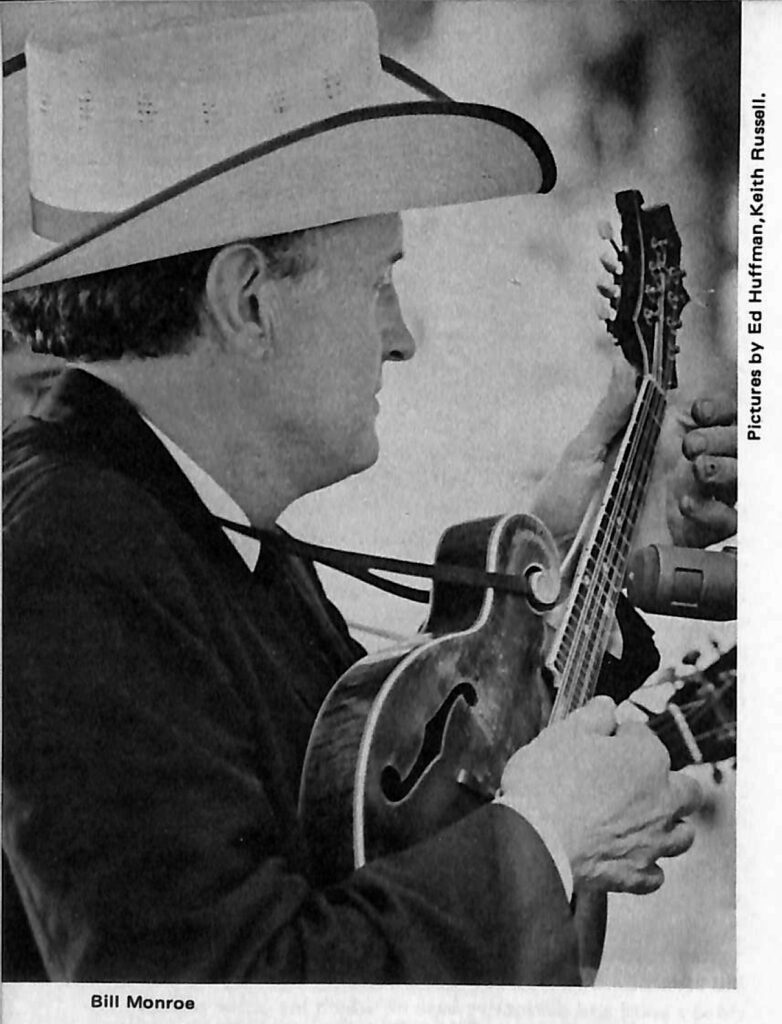

In the early years of bluegrass the mandolin was frequently overshadowed by both fiddle and banjo. Bill Monroe is by no means the only one who took up the mandolin because it was the only instrument not already spoken for by his musician friends. Fiddle tunes and banjo tunes have always been in far greater supply than numbers written for the mandolin. And, a few years back, when the pop music industry began to take notice of bluegrass instrumental sounds, the mandolin seemed to get little or no attention.

Lately, in the never-ending rush to replace one fad with yet another fad, it looks like pop may be coming around to the mandolin. Rod Stewart has used it on several of his hits, including ‘‘Mandolin Wind,” “Reason to Believe,”and “Maggie May. ” So have the Rolling Stones, Elton John, Bob Dylan, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, the Doors, Oliver, Ry Cooder, Jesse Winchester, the Band and the Byrds. While this may or may not have further implications for bluegrass, it does serve to remind us that the mandolin has undergone considerable development over the years and continues to show additional promise for the future.

Fifteen years ago, if you were talking to a bluegrass enthusiast about mandolin playing you’d have found—as you’d find today—that Bill Monroe was occupying a place of healthy respect in the the conversation. True, nearly all the bands which had achieved widespread popularity by the mid 1950’s utilized the mandolin to some extent, and much of the playing was outstanding. Pee Wee Lambert’s mandolin breaks on the Stanley Brothers’ early records weren’t fancy, but they were smooth and they were perfect for the songs they went with.

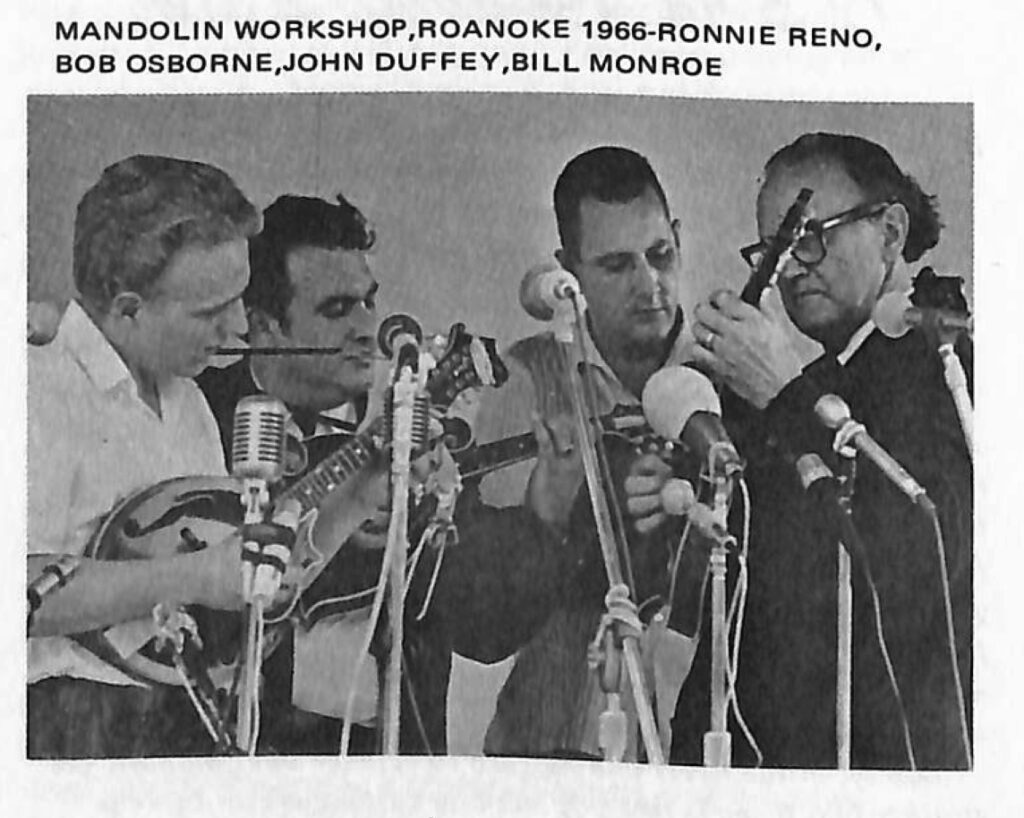

Red Rector had done some fast and extremely agile picking with Reno and Smiley on tunes like “Choking the Strings” and “Double Banjo Blues” and could also be heard playing very pretty breaks on Charlie Monroe’s “Down at the End of Memory Lane”, “Clock of Time” etc. Bobby Osborne’s mandolin on the Osborne Brothers’ instrumentals like “Hand Me Down My Walking Cane,” “Silver Rainbow” and “Wildwood Flower” was first rate and was very much his own.

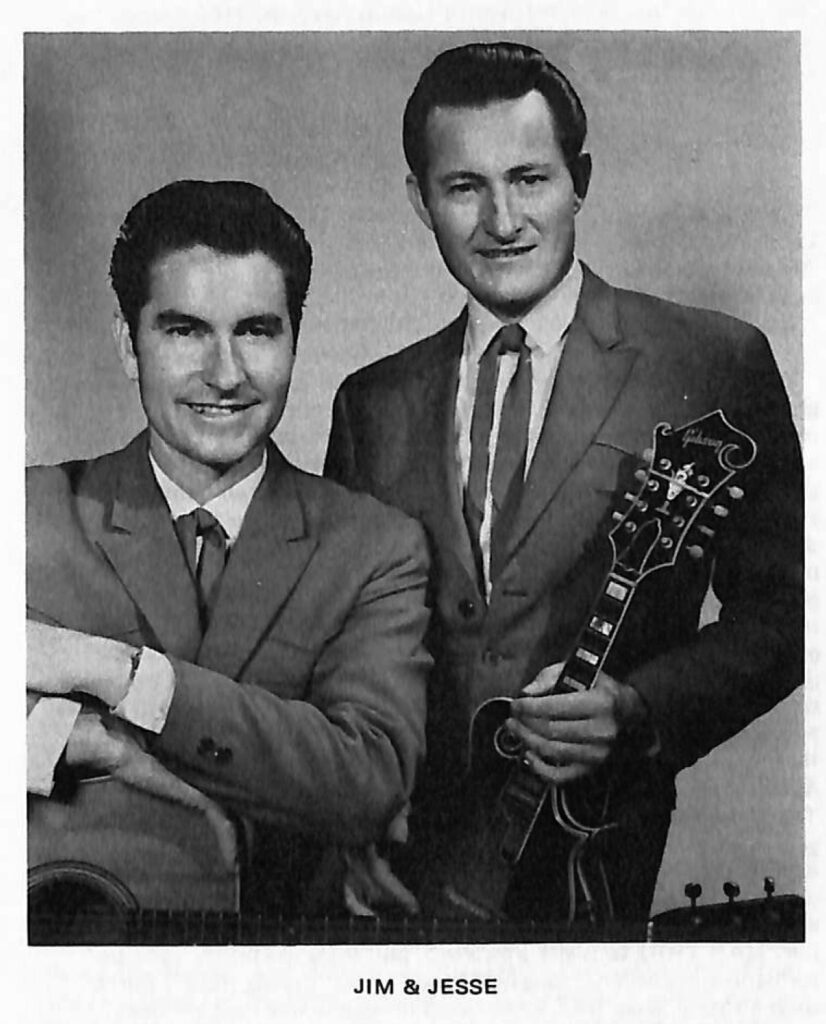

Benny Williams had a bit on Mac Wiseman’s “Crazy Blues” that made you wish you could hear him cut loose on a few more tunes. Jesse McReynolds not only played lovely conventional mandolin but stood out as important innovator with his “roll” style of playing that was so perfectly suited to Jim and Jesse’s “My Little Honeysuckle Rose,” “Memory of You”, “I Like the Old Time Way” and many more. Jethro Bums of Homer and Jethro didn’t record bluegrass music, but after hearing him play you could tell he knew things about his instrument that most mandolin players don’t approach in a lifetime. (The album “Down Yonder” by the Country Fiddlers and Wade Ray, recorded much later on RCA Camden features Jethro’s amazing picking.)

Nevertheless, in the midst of all this strong stuff it was Bill Monroe who stood out most. Bill’s rhythm playing provided a solid and distinctive base on which his music rested. Many people agreed with Carlton Haney that “Bill plays a different time than any other mandolin player” and felt that this was the most important single aspect of his band’s driving sound.

Monroe’s lead mandolin playing was, however, every bit as strong and distinctive, and perhaps a lot more obvious to the average listener. He could play smoothly and powerfully on slow songs like “In the Pines” or “Get Down on Your Knees and Pray.” He combined a strong syncopation with “blues notes” (minor thirds and sevenths) in medium tempo numbers like “New Muleskinner Blues” and “The First Whipoorwill”. And when he got wound up into playing fast and furious as in “Whitehouse Blues”, “Prisoner’s Song”, “Roanoke” etc., it didn’t seem likely that anyone else would come along and do them better.

In writing and recording instrumental tunes which primarily feature the mandolin, Bill was also way ahead of the competition. He played bouncy bluesy pieces like “Bluegrass Stomp” and “Bluegrass Special”. He returned the mandolin for a compelling and different sound on “Get Upjohn” and “Bluegrass Ramble”. And with “Rawhide”, “Bluegrass Breakdown” and “Pike County Breakdown” he gave aspiring young mandolin players something to sink their teeth into for years to come.

Skillful and inventive as many of the other mandolin pickers were, by the time Monroe had released all the above-mentioned mandolin tunes plus a few more, no one else had recorded a memorable mandolin number. And, while there were quite a few young guys working to learn Monroe’s playing note-for-note off the records, it was rare to hear anyone emulating the styles of the good mandolin players who recorded with other bands.

All in all, if you were just listening to records at the time, you might have been figuring that with the exception of Monroe’s band, the mandolin was going to remain a kind of fill-in instrument to be used chiefly for variety from the usual banjo and fiddle breaks. However, if you happened to be living in the Washington, D.C./Baltimore area, you might have been aware that below the surface, the caldron was bubbling considerably. From the middle to late fifties a number of new talents were boiling up into public view.

There was Earl Taylor with his forceful Monroe-influenced style. There was Bennie Cain playing a gentler, slightly old-time sounding mandolin. Jerry Stuart recorded just one tune (“Rocky Run” on the Folkways Mountain Music Bluegrass Style) but showed a promising sensitivity and original turn of mind. Smiley Hobbs, after a stint with Reno and Smiley, did some excellent mandolin work with Bill Harrell. Donna Stoneman was a major attraction not only because she was considerably better looking than most of the other mandolin players around, but also for her showy picking.

One of the most interesting musicians was Buzz Buzby. While there may have been players who knew more mandolin, Buzz was a heavy contender for the fastest right hand in the business. When he was feeling right he would squeeze out more notes per lick than you’d expect in three or four times that space. Buzz’s band, called the Bayou Boys, featured at various times such widely known musicians as Scott Stoneman, Bill Emerson, Charlie Waller, Don Stover and Pete (Roberts) Kuykendall. Buzz and the Bayou Boys released a series of singles, many of them highly inspired, on Starday and other labels.

Around the same time an energetic young mandolin player named John Duffey helped start a new band which would open up new musical territory to bluegrass. Leaving aside his contributions in singing, arranging, and songwriting, John’s powerful, showy and imaginative mandolin playing alone would have made him a prime asset to the Country Gentlemen.

His approach to the mandolin sometimes appeared to be aimed at seeing how many different and unexpected sounds could be coaxed, squeezed or beaten out of his instrument. In addition to his own impressive high-energy variations on Monroe-style mandolin playing, John did such unheard of things as playing breaks on three or four strings simultaneously instead of the usual one or two. He twisted the strings, he played jazz chords, played breaks alternating between first and fourth strings and sometimes he’d use fingerpicks instead of a flatpick. John used the mandolin as a principle instrument on such unusual (for bluegrass) instrumental numbers as “Sunrise” “Dixie Lookaway” (Dixie), “Backwoods Blues” (“Bye Bye Blues”), “Exodus”, “Windy and Warm” and many others.

Some traditional minded fans used to complain that what John played wasn’t really bluegrass. “You may like it or you may not, but it’s mine, ” he sometimes said of his unorthodox approach to the mandolin. (Occasionally he’d add: “What’s your contribution?”) As time passed the complaints dwindled and appreciation of John’s contributions grew to the point that his influence now shows clearly on records by younger bands in such diverse locations as Boston, North Carolina, Wisconsin, California and Japan to name just a few.

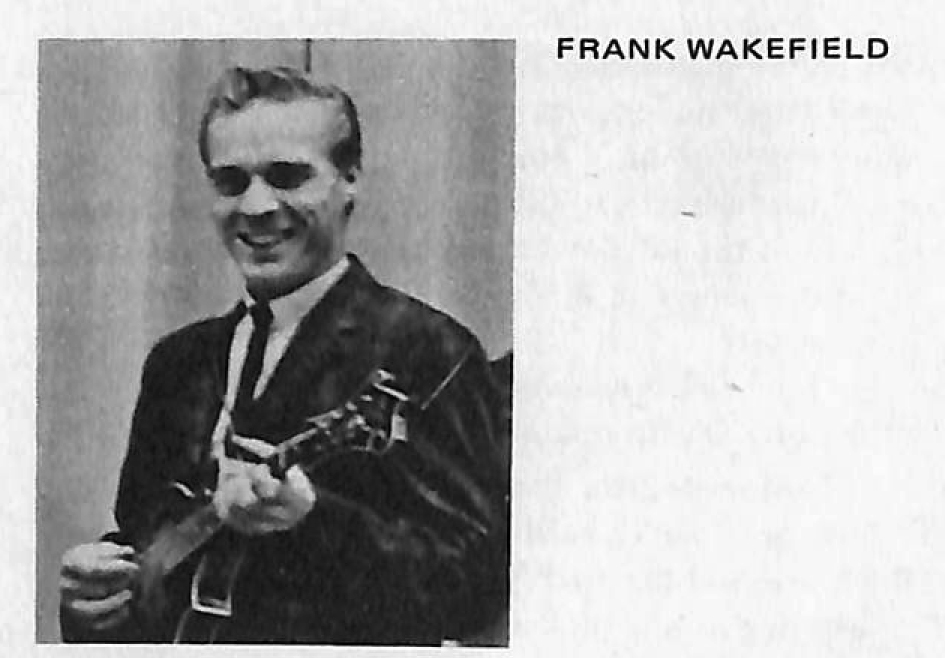

1961 saw yet another important mandolin player making his first appearance in Washington: (Phone rings).

Frank Wakefield: “Hello, this is you speaking.”

Puzzled voice on the other end (after a pause): “Who is this?”

Frank: “This is you speaking.”

Voice: “I must have the wrong number.” (Hangs up)

(A minute passes. Phone rings again.)

Frank (answering it): “The number you have reached is the one you have just dialed.”

The above could have occurred in Washington in 1961 instead of in January 1972, as it did at the apartment of a friend in Boston, Massachusetts. Today, at 37, Frank seems as whimsical and loose as he did when he first arrived with Red Allen in Washington and promptly earned deep respect for his ability on the mandolin.

During the years with Red and later with the Greenbriar Boys, Frank won himself a loyal following of enthusiasts who swore by his own individual version of Monroe-style bluegrass picking. His Folkways album with Red Allen and his work on Vanguard with the Greenbriar Boys are perhaps his most widely heard recordings to date, although he has recorded on several other labels as well, including Starday, Rebel and Silver-Belle. Lately he has recorded with pop singer Oliver and has completed his own album for Rounder Records.

In recent years Frank began playing some tunes unlike anything he—or anyone else—had previously recorded. The tunes had rather strange names such as: “Jesus Loves His Mandolin Player No. 16” etc. He is currently working on “Jesus Loves His Mandolin Player No. 30.” Frank describes why he named his tunes as he did: “When I was 16, I had my hands prayed over in church, and that was the reason I was able to get as good as I could on the mandolin. One day I was to play at the Performing Arts Center in Saratoga (New York) and suddenly when I was supposed to go on, I couldn’t play at all. I finally realized that I had been taking all the credit for my playing without giving any to the Lord, where it belonged. After I realized it, I told the people in the audience the story, and I was able to play again.”

The following is a brief discussion of Frank’s playing prepared for the notes for his upcoming Rounder album: Records by Bill Monroe, Jim and Jesse McReynolds, and the Blue Sky Boys are Frank’s earliest recollection of the kind of playing which aroused his interest in the mandolin. Like many another aspiring young picker, he worked especially hard at copying Monroe’s style, which stood out from others in its aggressive rhythmical drive as a backup instrument and in the “blues notes” and distinctive syncopations which figured prominently in lead playing. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Frank succeeded to an astounding degree. So complete became his grasp of Monroe’s approach to the instrument that many people felt that when Bill’s time came to retire, Frank would be the only musician capable of continuing the Monroe style in its true form.

Monroe’s view was a little different, however. Frank recalls a jam session with Bill a few years ago during which Bill seemed to be intent on seeing how hard he could push Frank’s abilities. Apparently satisfied, Monroe finally conceded, “Well, you’re about as good as I am at my style. Now let’s see you get a style of your own.”

In actual fact, Frank has never limited himself to simple imitation. His “New Camptown Races”, first recorded in 1952 (in the unlikely key-for the mandolin-of B flat), showed plenty of original thought. So did his later recordings.

Particularly striking was the way Frank began utilizing the “blues notes”, using them as part of a minor scale against major chords played by the accompanying instruments. Nevertheless, for many years his playing did consist essentially of Monroe’s style augmented by his own ideas.

Rounder Record’s new album presents for the first time on record Frank’s answer to Monroe’s challenge. On his bluegrass numbers, it is true, Frank generally takes a somewhat Monroe-influenced approach. (Compare the beginning of Frank’s “Sleepy Eyed John” with the original “Get Upjohn” by Monroe or Frank’s break on “Nobody’s Darling But Mine” with Monroe’s on “The Prisoner’s Song.”) His instrumentals in the “Jesus Loves His Mandolin Player” series, however, introduce some wholly different concepts via what Frank calls his “classical style.”

Frank asserts that he did not consciously imitate classical compositions. “If I ever picked up classical music on the radio I’d switch right away to the nearest country station.” Nevertheless, his new style does depart from previous bluegrass mandolin playing in directions which strongly suggest classical forms.

In bluegrass mandolin when two strings are hit simultaneously, the notes sounded normally consist of the melody plus a simple harmony, usually a third or a fifth above the melody. Frank, however, plays passages in which the two parts move independently—that is, one part might move upward as the other moves downward so that the effect is that of melody and countermelody. In some cases three parts instead of two are played.

Frank has also developed some interesting right hand techniques which produce a very full sound. While playing one part on the low strings with a tremolo he reaches over to the high strings between tremolo strokes and plays individual single notes without breaking the rhythm. At other times he plays a tremolo on the high strings and, again between strokes, hits individual bass strings. On “Jesus Loves His Mandolin Player No. 2” he achieves additional complexity by the use of a fingerpick on the third finger of the right hand. In this way Frank is able to play separate parts which are not on adjacent strings at precisely the same time.

These technical innovations combined with Frank’s mastery of bluegrass mandolin playing and with his keen musical sense produce a unique style so full that it requires no accompaniment by additional instruments. In creating this new approach to his instrument, Frank has opened the door for a broader range of musical development of the mandolin. And, perhaps somewhere there is a young picker who will successfully set out to master Frank’s style, and end up having Frank tell him, as Monroe told Frank: “Now let’s see you get a style of your own.”

During the period when the Washington/Baltimore players were first making their presence felt, the older established bands did not seem to share any common view about the mandolin’s common role. Some, like Flatt and Scruggs and like Reno and Smiley, seemed less and less interested in it.

The Stanley Brothers featured Bill Napier’s skillful playing for a while and then seemed to lean toward the lead guitar in its stead. Bobby Osborne’s mandolin seemed to be given a major role infrequently, but every so often (as on his instrumental “Surefire”) it was right out in front again.

On the other hand, there was Jesse McReynolds. From his superb work discussed earlier, Jesse went on to explore still more deeply the possibilities inherent both in his fast, clean conventional picking and in his own original “roll” style. Dazzling and complicated instrumentals like “Farewell Blues”, “Border Ride”, “Dill Pickle Rag”, “El Comanchero”, “Sugar Foot Rag”, and “Tennessee Blues” were the result. (Not all are available on record, unfortunately.) So were a host of exciting breaks on songs like “Standing on the Mountain”, “Salty Dog Blues”, and (“I’m Going Back to) Alabam”.

The 1960’s saw a new crop of young pickers emerge, some of whom stayed with it and some of whom left for other instruments or different professions. Some of the best were Roland White (now with Lester Flatt), Ronnie Reno, Frank Wakefield protege’ David Grisman, Sam Bush (of the Newgrass Revival), Jimmy Gaudreau (now with the II Generation), and Frank Greathouse (of the New Deal String Band). None have, perhaps yet had the profound impact on bluegrass of certain of their elders. Among them, however, are some exceptionally talented musicians who have shown the ability to learn from what has gone before, as well as to add original and exciting concepts of their own.

The above is clearly far from a complete discussion of bluegrass mandolin playing. Much more space would be needed to trace all the subtleties of Bill Monroe’s musical development, let alone deal fully with the styles of other highly regarded players like Paul Williams, Everett Lilly, Herchel Sizemore, Joe Val, Doyle Lawson and others. However, a survey of the various tunes and songs referred to throughout the article does point up the fact that bluegrass mandolin is far from a static skill. It is a vital and variable component of a music which survives and flourishes through a ceaseless blending of the old with the new.