Home > Articles > The Archives > Bill Napier—Creative Instrumentalist

Bill Napier—Creative Instrumentalist

By Ivan M. Tribe and John W. Morris

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1980, Volume 14, Number 7

Between 1958 and 1968, Bill Napier established himself as one of the top musicians in bluegrass. Beginning as a sideman with the Stanley Brothers and then as half of the Moore and Napier team, Bill displayed his multiple talents on mandolin, lead guitar, and banjo. For the last decade, Bill has been largely inactive, but some of his innovations continue to be heard today.

Bill Napier was born in Wise County, Virginia, on December 17, 1935. When he was still a small child, his parents moved to the hamlet of Harman, Virginia, which is close to the somewhat larger town of Grundy. Unlike many future bluegrass musicians, Bill did not come from a particularly musical family. One of his grandfathers played the old-time banjo and could cut-up as a showman in the manner of Uncle Dave Macon, but Bill never saw the old gentleman. From a family of eleven children, only Bill and one of his brothers showed any interest in music at all.

Nonetheless, Bill took considerable interest in music, especially that heard on WCYB in Bristol. He recalls the Stanley Brothers as being his early favorites. He also liked Charlie Monroe and his Kentucky Pardners. Among individual musicians and instruments, he became especially fascinated with Pee Wee Lambert and the mandolin. Since the Stanley Brothers played frequent shows in the community, Bill had opportunity to get some first-hand tips from Lambert. Bill Monroe also played a few shows in the area and he too became an inspiration to young Napier.

When Bill reached his late teens, he joined the migration of Appalachian youth to the north and sought industrial employment in Detroit. When he started drawing a regular check, Bill obtained a good mandolin and began to develop his talents seriously. Soon he found himself working and playing with other mountain musicians in the Motor City.

One duo that Bill Napier played with quite a bit was Curly Dan and Wilma Ann. This husband and wife team was just beginning a lengthy tenure as fixtures on the Detroit bluegrass scene. Bill helped them by playing mandolin on their first session on the Fortune label. The songs were “Sleep Darling” and “My Little Rose.”

Bill also met Jimmy Williams who had played mandolin with both the Stanleys and Mac Wiseman. Jimmy suggested that Bill’s talents were of sufficient quality to rate a tryout with the Clinch Mountain Boys. Bill contacted Carter Stanley and subsequently went to Bristol for an audition. This first attempt to break in to the big time did not prove fruitful. Bill went back to Detroit and practiced a bit more and a few months later he returned to Bristol as a full-fledged Clinch Mountain Boy.

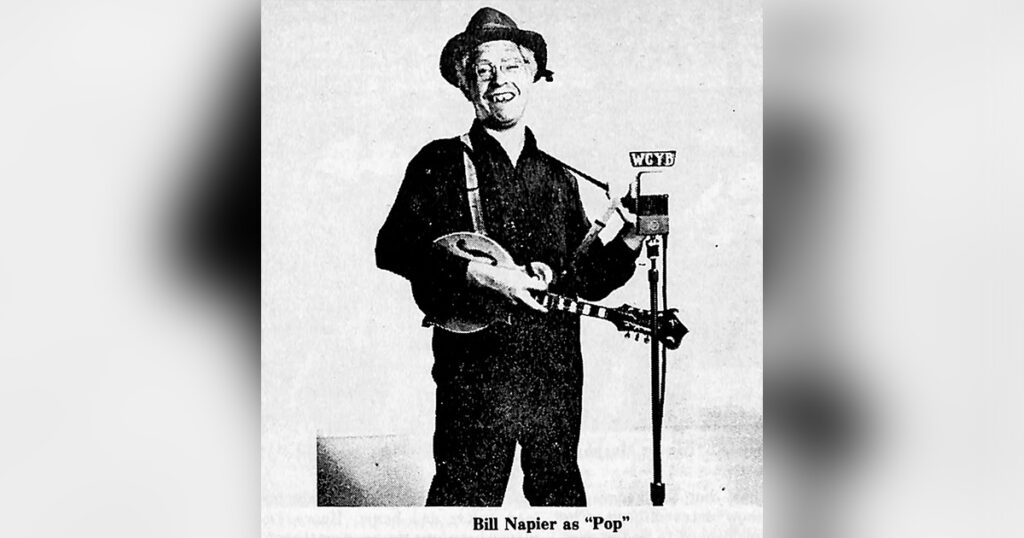

Bill Napier remained with the Stanley Brothers for about three years. In addition to playing mandolin, Bill also did much of the booking work and played the comedy role of “Dad” or “Grandpop” Napier. Bill apparently enjoyed this role immensely and so did the audiences. Although not much bluegrass comedy is heard today, a bit of Dad Napier survives on the Stanley’s King recording of “Train 45” where Bill executes a couple of lines in his now nearly forgotten role. Carter asks various members of the band where they are going and Napier replies in a falsetto old man’s voice, “Why, I’m goin’ down about Grundy, Virginia, boys! Where you Stanley Brothers aheadin’?”

BilI had been with the group for about four months—in November 1957—when the Stanleys went to Nashville for some Mercury recordings. In addition to their band of Ralph, Carter, Bill, and Curley Lambert (on bass), Benny Martin and Howdy Forrester joined them to play twin fiddles. For Bill, the most significant portion of the four-song session was the waxing of the original mandolin instrumental, “Daybreak in Dixie.” This tune has been called “one of the few mandolin instrumentals other than Bill Monroe’s…carried into tradition.” Bill wrote this classic instrumental and gave it to Carter Stanley. The other songs recorded on that session included “If That’s The Way You Feel,” “A Life of Sorrow,” and “I’d Rather Be Forgotten.” It’s interesting that Roy Wiggins played electric steel on “If That’s The Way You Feel.” A little later they recorded the tragedy song, “No School Bus In Heaven,” for Mercury back at WCYB with Ralph Mayo on fiddle.

During the time that Bill worked with the Stanley Brothers, several good sidemen worked with the band. Often they stayed only for brief periods. Jack Cooke, Curley Lambert, and George Shuffler were among the bass players. Chubby Anthony, Benny Williams, and Ralph Mayo were among the fiddlers. Although Joe Meadows left the group before Bill’s tenure began, he did come back and fiddle for them on one Starday recording session—the one that resulted in “Gonna Paint the Town.”

Bill enjoyed his work with the Stanleys although he failed to get rich as a Clinch Mountain Boy. At the time, however, he considered the pay adequate. The Clinch Mountain Boys worked pretty regularly in school auditoriums, theaters, and drive-ins during the summer. Sometimes they gave matinee shows to school children, too, occasionally as many as four in one day. They received no pay for their Farm and Fun Time appearances at WCYB, but sold songs books and advertised their show dates.

Bill’s salary varied somewhat with the fortunes of the band as they generally worked on percentages. He recalls that his pay usually averaged $50 to $75 weekly and on occasions tended to be higher or lower. Bill usually lived at the YMCA in Bristol and during instances when the Stanleys did not work on Sundays, he went back home to Dickenson County and they all went to church with Mrs. Lucy Stanley. Bill considered this a very rewarding experience.

The Stanley Brothers recorded on Starday and King after their Mercury days ended. Although this material is considered excellent bluegrass today, record sales at that time tended to lag somewhat. Syd Nathan of King believed they needed something innovative in their sound. For a time they toyed with the idea of adding an autoharp to their band and Bill began to play one. However, one day almost by accident, they hit upon the lead guitar. Bill was putting a new set of strings on Carter’s guitar and began to pick out a mandolin tune—“Rawhide”—on that instrument.

Carter quickly took an interest and the two of them thought that this might be the needed new sound. When the Stanleys went back to record with King again, Syd Nathan agreed. From that time onward, the lead guitar became a part of the Stanley sound. Bill explains it simply that he just adapted mandolin licks to the guitar. At any rate, record sales picked up again with Bill abandoning the mandolin for the lead guitar.

Bill did not actually stay with the Stanleys beyond one or two recording sessions that utilized the new sound. Charlie Moore led a South Carolina based band, the Dixie Partners, and he booked the Stanleys to work some shows with his group. This incident resulted in Charlie and Bill striking up a friendship and to Bill’s joining forces with the Dixie Partners. So in 1960, the team of Moore and Napier was formed.

By the time Bill Napier joined Charlie’s group, the Dixie Partners had already been going strong for about three years. They had established themselves on television in Greenville and Spartanburg, South Carolina and recorded some eight numbers on Starday. Early members of the group included Ansel Guthrie on mandolin, Dan Padgett on banjo, Duck Sisk on fiddle, and Lindy Clear on bass. After Padgett’s departure, Kent Wiseman played banjo until his tragic death. Henry Dockery also became bass player for the group and remained with them for several years.

Moore and Napier made their first recordings together in 1960 for the American label in Cincinnati—an early Wayne Raney concern. They cut a total of ten songs in two sessions. However, only two seem to have been issued, “Big Daddy of the Blues” and “The Story of Love.”

Eventually, a former sales manager at the television station in Spartanburg lured Bill and Charlie away from South Carolina to Panama City, Florida. They played six shows weekly at WJHG-TV and videotaped shows for television in Pensacola and Orlando. Their sponsor paid them a salary, but the geographic location made show dates difficult. The show at Pensacola proved to be the most lucrative in terms of personal appearances.

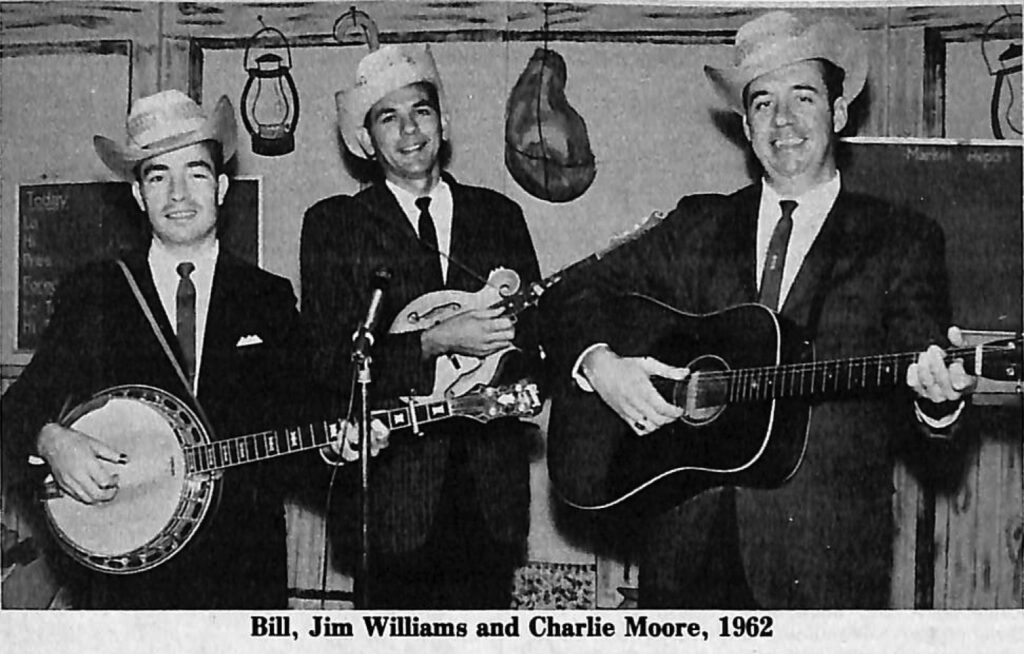

Since Charlie and Bill did not take a banjo picker to Florida with them, Bill Napier now added the banjo to the list of instruments he had mastered. Bill never played mandolin during his days as a Dixie Partner, but divided his time between lead guitar and banjo. Henry Dockery played bass for a time during their Florida days and when he left, Curley Lambert came down and worked with them for a while. Jimmy Williams came down and played mandolin and sang tenor. By the time the Dixie Partners made their first recordings for King in late 1962 or early 1963, Dockery had returned and Curley Lambert rejoined the Stanley Brothers.

The first Moore and Napier King album, “Folk ‘N Hill,” featured Bill playing lead guitar and singing baritone. Charlie sang lead and Jimmy Williams, tenor and mandolin. Dockery on bass and Ray Pennington on drums rounded out the session. The first album had fourteen numbers on it including their best known song, “Truck Driver’s Queen,” which Jimmy Martin later recorded on Decca.

After the Dixie Partners lost the television show at Pensacola, they decided to give up the Panama City shows and return to Spartanburg. By now their King Records were making a wider name for them and they survived on personal appearances. In addition, they eventually got back into early morning television.

Quite a number of well-known sidemen spent some time with the Dixie Partners during the mid-sixties. Former Clinch Mountain Boys Ralph Mayo and Benny Williams worked with the group at various times. The late Jimmy Lunsford played fiddle with them for a time and recorded one album as did Johnny Dacus. Audie Webster—one of the Webster Brothers that had once recorded with Carl Butler—played mandolin and sang tenor for a time, working on two record sessions. Eb Collins also worked quite a while on mandolin and fiddle. Several Ohio musicians also assisted on their King recordings at various times including Paul (Moon) Mullins on fiddle, Sid Campbell on mandolin and guitar, Jim McCall on mandolin and tenor vocal, and Benny Birchfield on bass. In all, Charlie Moore and Bill Napier recorded some nine albums on King and 108 songs.

Charlie and Bill also wrote quite a number of songs during their years together. One of the more unusual characteristics of their songwriting was that some of it took place in the recording studios during sessions. On at least four or five occasions, the duo put the songs together, rehearsed them a time or two, and recorded them all within the space of one or two hours. An example is the album “Country Music Goes to Vietnam.” Another unusual incident that took place in the King studios happened when Charlie and Bill contributed some rhythmic hand clapping on a recording for soul singer Hank Ballard. Some may remember Ballard also as the composer of “Finger Poppin’ Time,” perhaps the most unusual song ever recorded by the Stanley Brothers.

Charlie and Bill worked together until 1968 when they dissolved their partnership. As Bill put it, they separated as friends and have remained as such. Bill simply needed a rest and had to get off the road for a while. After a short lapse, Charlie reorganized the Dixie Partners and has continued steadily ever since despite some occasional setbacks due to poor health. Since Bill’s departure, Charlie Moore’s Dixie Partners have had nine more album releases on the Country Jubilee, Wango, Vetco, and Old Homestead labels. Bill has helped on some of those sessions.

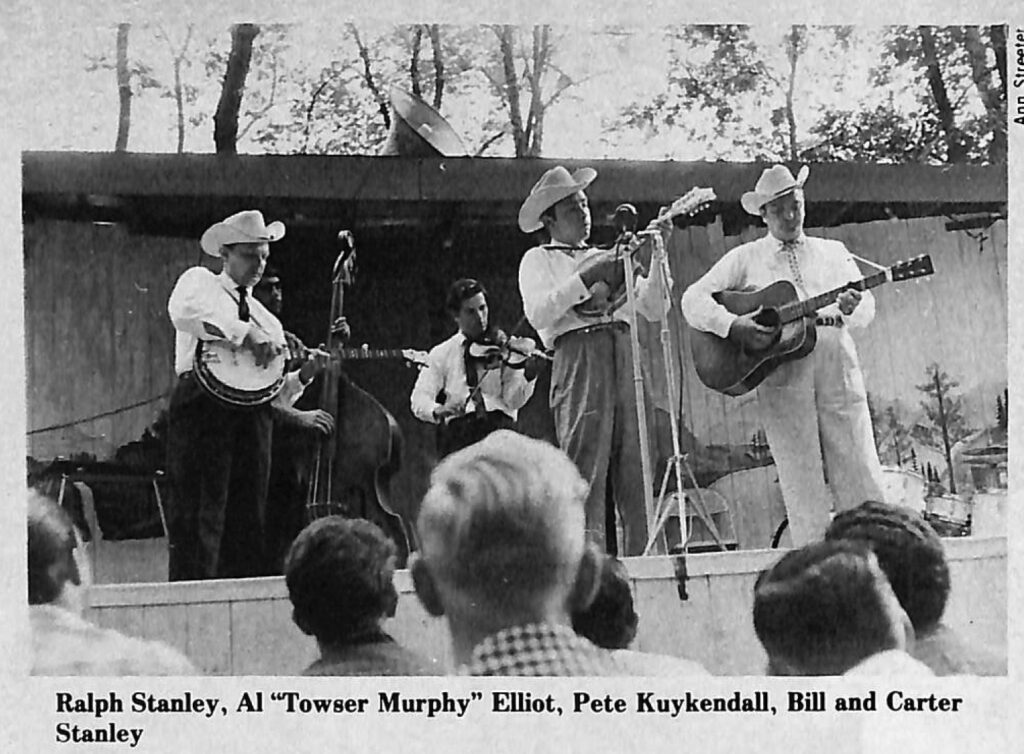

In the decade since he quit active playing. Bill Napier has lived mostly in the Detroit area. He plays a bit now and then and has helped Curly Dan and Wilma Ann on some of their recordings by playing lead guitar. Bill also works a few shows on occasion with Charlie Moore. He has also worked a bit with the Toledo-based L.B. Siler and the Round Mountain Boys. Recently, he and Charlie did a reunion album on Old Homestead which has been well received. Al “Towser Murphy” Elliot, an old Stanley sideman, plays mandolin and sings tenor. The album contains a variety of older and newer songs including “My Heart’s Bouquet,” a fine country tune recorded by Little Jimmy Dickens some 30 years ago. Bill also helped Wendy Miller and Mike Lilly on sessions for an instrumental album. Bill maintains an interest in his music and from time to time talks about getting back into the business on a regular basis. However, to date this has failed to happen.