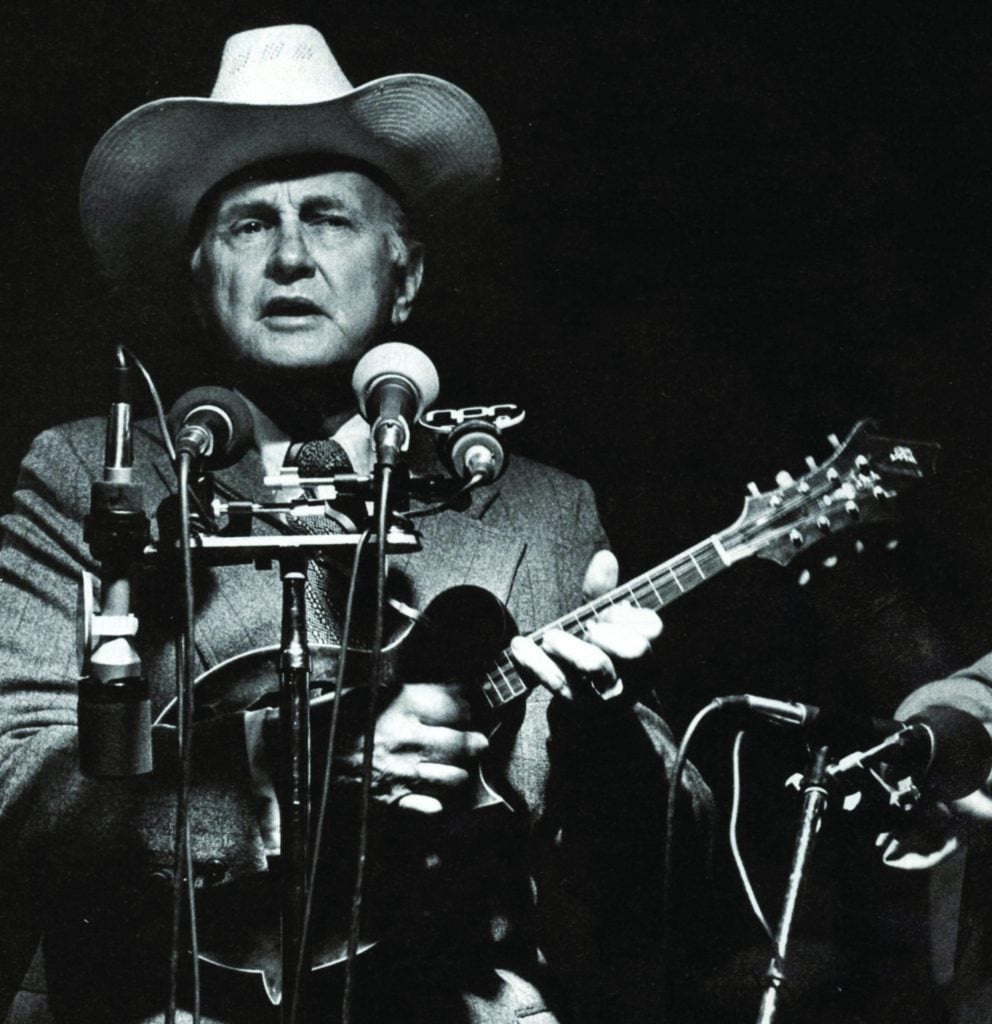

Bill Monroe’s Gouged Headstock Veneer

If you look at any photo of Bill Monroe holding his mandolin taken between 1950 and 1980, you will notice that the company name, which usually graces the instrument’s headstock, is noticeably missing. Most die-hard bluegrass fans will know that very early in the 1950s, Bill Monroe shipped his mandolin to the Gibson company for repair. This is the Gibson mandolin that Bill had purchased at a barber shop in Miami, Florida, in about 1943. In some interviews, Bill said that he paid $125 for it. In others, he says $150. It is a Gibson F-5 Master model signed by Gibson’s acoustic engineer, Lloyd Loar on July 9, 1923 (serial number 73987).

Gibson kept the mandolin for four months and returned it without executing all of the work that Monroe had requested. Not satisfied with the work, he gouged the Gibson logo out of the peghead overlay with a pocket knife.

Recalling the incident in a radio interview in 1966, Monroe said, “Well, I tell you…the mandolin I have is a Gibson, of course, and I had to send it back to the factory—every time I’d need frets in the mandolin, I would get a new fingerboard put on it. And this time that I sent it back—the neck had been broke off; it needed a fingerboard; it needed re-finishing; it needed keys…it needed everything, mind you. So, I sent it back and they sent it back to me with just the neck put back on and that was about all. I don’t know whether they just overlooked it or something and didn’t do everything I said or not. But it didn’t make me feel good, so I thought, well, I didn’t have to have the name of Gibson—they had never done much for me…But they have done a lot for other people and I guess it’s a good thing that I got this Gibson mandolin, because I do think it’s the best mandolin—especially for me—in the country.”1

Monroe held his grudge against Gibson for 30 years, and it probably would have continued had representatives from Gibson not reached out to Monroe. Over the course of Monroe’s 30-year grudge, Gibson had occasionally attempted to contact Monroe, but their efforts received no response. Finally, in 1980, they made a more concerted effort. In an article written for Mandolin Café (mandolincafe.com) in 2009, author Bill Graham reported:

“Two Gibson employees in product development and artist relations, Rendal Wall and Pat Aldworth, went to Nashville to meet with Monroe.

‘It was a long, drawn out process,’ said Wall. ‘I met with Bill many times backstage at the Opry. It took many trips before he would even talk to me about it.’

Finally, Wall was invited into the dressing room to discuss the matter.

‘I said Bill, you’ve had this grudge against Gibson for a long time,’ Wall said. ‘We’re wanting to kind of make up and get the headstock repaired.’

Monroe said he’d think about it.

Several weeks later, Wall was backstage at the Opry when someone tapped him on the shoulder and said Monroe wanted to talk to him in the dressing room about the mandolin repair. ‘He said, ‘I’ve been thinking about that, and why don’t you go ahead and do that,’ Wall said.”

In 1980, Gibson replaced the headstock veneer and fixed the treble side scroll, which had been knocked off the mandolin. The repair work was done by Dick Doan. Gibson presented the repaired mandolin to Monroe at his office on October 8th, 1980. Aldworth asked Monroe if he wanted to keep the old headstock overlay. Monroe said, “You can have it.”

Aldworth took the gouged pearwood headstock overlay back with him to Kalamazoo, Michigan. It stayed there until Aldworth put it up for auction in December of 2009 at Christie’s auction house in New York. He made Wall a partner in the sale. Experts at the auction house estimated that the item would sell for between $5000 and $7000. Sources indicate it sold for considerably more than that.

The two final bidding parties for the headstock overlay were the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum in Owensboro, Kentucky bidding against John Carter Cash & Laura Weber Cash (now Laura Weber White). The museum was outbid. In an interview conducted by mandolincafe.com in 2010, Laura said, “When we were bidding, we had no idea that we were bidding against the museum. We were the final 2 bidding parties. If we had known, we would not have kept going. John Carter and I are very dedicated to music history and its preservation. I’m captivated by music history. I had actually put in an application in the archives at the Country Music Hall of Fame long before I ever met John Carter. And, of course, he has the history on both sides: his father being Johnny Cash, as well as the rich musical history from his mother, June’s side, the Carter Family.”

In 2018 Laura Weber White loaned the artifact to the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum just in time for the grand opening of the new building in downtown Owensboro, Kentucky. The famous peghead overlay remains on exhibit at the museum and will be on displayed until at least 12/31/21. If you have a chance, take the trip to Owensboro to view this historic item and many other bluegrass artifacts in their collection.