Home > Articles > The Archives > Bill Keith

Bill Keith

Reprinted From Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

December 1975, Volume 10, Number 6

This article came from information compiled by Tony Trischka, noted banjo player in his own right, in preparation for his forthcoming book “Melodic Banjo” to be published by Oak Publications in the early part of 1976.

Bill Keith is what you might call an overnight legend. Back in 1962, Bill and guitarist Jim Rooney put out “Livin’ on the Mountain,” a hard to find album that became an underground bluegrass classic as soon as it hit the turntable. The main reason for all the excitement was Bill’s revolutionary banjo playing. From out of the blue, here was someone who could play fiddle tunes note for note without batting a fingerpick. The record featured “Keith-picking” versions of “Devil’s Dream” and “Sailor’s Hornpipe” plus an absolutely astounding break to “Salty Dog.” Banjoists from Maine to Maryland (it was primarily a Northern phenomenon at first) began picking up on this new style which not only enabled them to pick out exact melodies with ease, but also gave them a set of licks and runs that was entirely different from that of Scruggs’ style.

With an eye towards fairness, it should be mentioned that Bobby Thompson had developed his own version of this fiddle tune style in 1957, several years before Bill, and had recorded fragments of it on Jim and Jesse’s 1958 recordings of “Border Ride” and “Dixie Hoedown.” However, Keith did work independently of Thompson and was the first one to give it wide exposure, largely through his work with Bill Monroe.

Born in October, 1939 in suburban Boston, Bill’s earliest musical experience came in the form of piano lessons. During this time he learned a lot about chord and scale theory, knowledge that would serve him well in later years. In fourth grade he switched to tenor banjo, which held his interest until the folksong revival swept him up in 1957. At that point he began listening to Pete Seeger on the Weaver’s records and realized that the music he was hearing was impossible to play on a four string banjo. So during his freshman year of college at Amherst he invested $15.00 in a five string and bought the Pete Seeger instruction book. “He said in there, go out and buy some Earl Scruggs and Don Reno records, and so I did. But meanwhile, I couldn’t wait to get to the back of the book where the interesting strums were. You know, the rhumba and the flamenco.” After two weeks he got over the initial dislike of Scruggs’ style and set out to learn Scruggs’ breaks note for note. “I thought he was a pretty good model because he played with a kind of taste that was really good, and a lot of technique that wasn’t played to show off the technique per se. Since I had already played the tenor banjo I didn’t worry about my left hand as much and I paid a lot of attention to the right. So that may be another reason why Scruggs struck me as a good model.” In those early years of playing, Keith devised his own system of tablature and began to transcribe Earl’s breaks exactly as they appeared on record. He also did a lot of listening to Jim and Jesse’s banjo player, Allen Shelton and Boston banjo great, Don Stover. It was undoubtedly the combined effect of these three men which added the all important drive and bounce to Bill’s music.

Over the next few years Bill solidified his playing by gigging at folk clubs and bars in the New England area with his roommate, Jim Rooney, and by the end of 1960 he had begun to work on his own innovative style. The first measure of Bobby Thompson’s break to “Dixie Hoedown,” a Don Reno lick in the chorus of “Banjo Signal,” and some lessons from Don Stover provided the initial inspiration. But the most direct influence came from a local fiddler, June Hall. “A neighbor’s wife played the fiddle and I used to go down there Wednesday nights and play banjo to her fiddle, and it just occurred to me that it should be possible. So I worked out “Devil’s Dream.” Then for a long time I didn’t put it to use in any other tunes.” “Sailor’s Hornpipe” was the next tune he worked up within the melodic style, and this, coupled with “Devil’s Dream,” comprised Keith and Rooney’s “hit” instrumental medley. It was this medley that won for Bill the Philadelphia Folk Festival banjo contest in September 1962. It’s interesting to note that Eric Weissberg and Marshall Brickman were the first ones to actually record a full scale “Keith-style” tune with their double banjo version of “Devil’s Dream,” released by Elektra in 1962. “Both of them were in town with the Tarriers (a New York based folk group), and they came into the Club 47 where Jim and I were playing. We played our medley, our big instrumental, I think we played it once a set at that point, and they heard it and looked at each other and then a couple of months later they had their record out.” Not to be denied, Keith and Rooney soon had their own album out, and word of Bill’s prowess began to spread.

By the end of the year he had his first professional job playing with Red Allen and Frank Wakefield in the Washington, D.C. area. Wakefield was at the height of his mandolin powers, and his combination with Red, Bill, and Tom Morgan on bass made for a potent sound.

At one point during this period Keith went to nearby Baltimore to see a Flatt and Scruggs concert. After the show he met Earl, and found out that he was putting together a banjo book based on some of his recordings. Bill then mentioned to Scruggs that he had written out tablature for many of the tunes to be included in the book. Obviously they would have to get together. So Earl invited Bill to come to Nashville, unknowingly setting the stage for Bill’s tenure with Bill Monroe. Jim Rooney provides these details: “Earl brought him down to the Grand Ole Opry, backstage, and Bill was playing “Devil’s Dream” and “Sailor’s Horpipe,” which had become by that time his masterpiece, and Monroe and Kenny Baker came into the room, heard it, and went out again. A little later on Kenny came back in and told Bill, “Anytime you want a job with Monroe, it’s yours.” Not wishing to keep Monroe waiting, Keith went back up North, settled his affairs with Allen and Wakefield, and returned to Nashville in March of 1963.

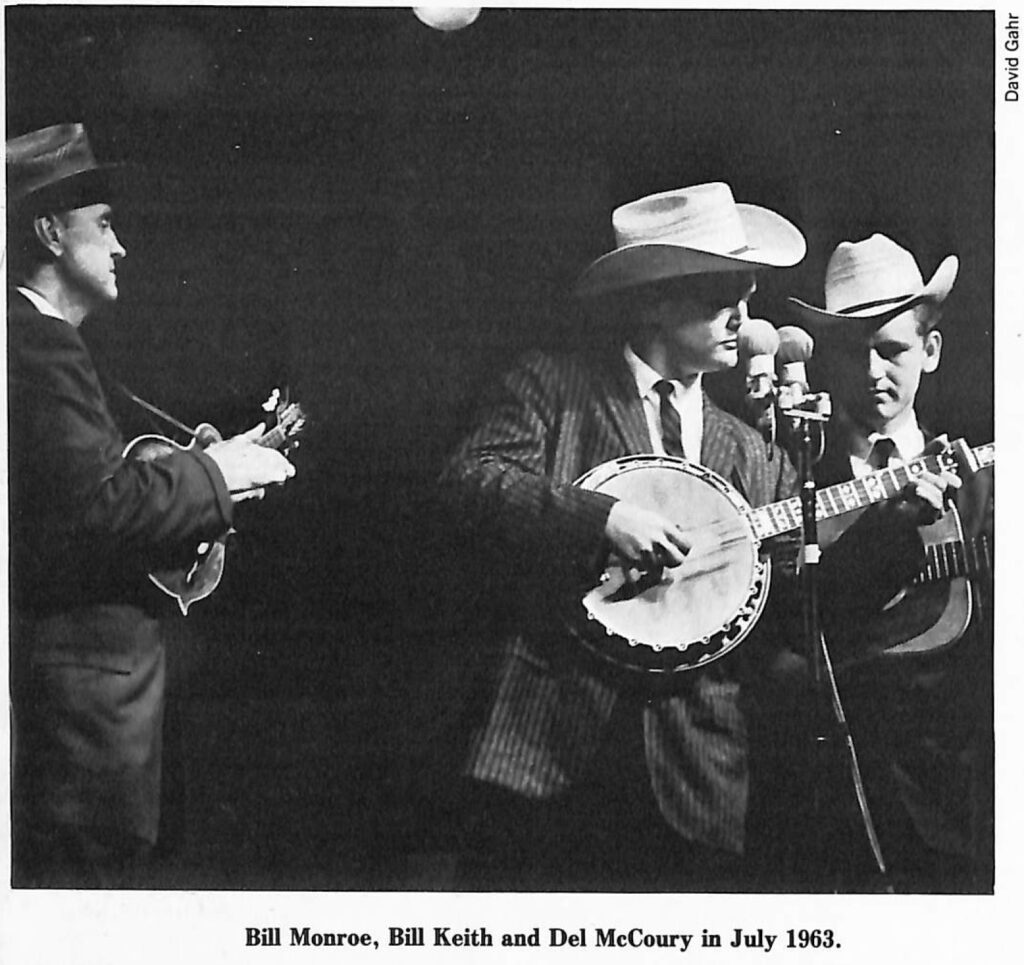

At that time Del McCoury was the banjoist for the Bluegrass Boys, so Monroe announced to Del that he was going to play guitar, and that Bill, or Brad as Monroe preferred to call him, was going to be the new banjo player. Within ten days of joining Keith found himself in a recording studio laying down such Monroe classics as “Salt Creek,” “Shenandoah Breakdown,” and of course, “Devil’s Dream” and “Sailor’s Hornpipe.” It was apparent that Monroe wanted to get this new banjo sound out to the public as soon as possible. But as exciting as this edition of the Blue Grass Boys was, times were tough. Jim Rooney gives this description of life on the road in 1963: “Monroe was at one of the lower points of his entire career. They were traveling in an Oldsmobile station wagon which had well over 300,000 miles on it. Ralph Rinzler was trying to manage Bill, but it wasn’t happening. Two times, I believe, while Keith was with him, they drove straight from Nashville to L.A. to play the Ash Grove and maybe one or two other gigs, and then straight back in a station wagon with five people and a bass on top, all the instruments and everybody’s clothes. It was very funky. It was a real eye opener. But I think the challenge was enough so when they did get to play…well I heard them several times and it was electrifying. There was no question that Monroe responded to Keith, and vice versa. Everybody on the Opry was talking about it.”

For all the above mentioned rigors of the road, Bill was finally getting his banjo style exposed to a large number of people. However, as his tenure with Monroe continued, the melodic aspect of his music began to change. “It’s funny, the more I played with him, the less it seemed that some of that stuff worked to use just as ornaments to a tune. I mean it was great to use for leads, but just to throw in this stuff and splash it up seemed wrong. So I was using less and less of that as time went on.”

Strangely enough, Bill never sat down to learn a lot of fiddle tunes from Monroe. The influence was more subtle. “He would never really spell things out, but when he was pleased with the way things sounded, you could tell. And so obviously you’re trying to play something that turns him on, and you just try different things and you seem to notice what works; and what seems to work a lot of the time is just real straight, hard driving…which doesn’t mean uncomplicated, but it doesn’t mean filled with flowery frills and phrases. He’s very much into a lot of rhythmic things, which is a great right hand thing anyway, although they can sound really simple. Like “Santa Claus” (from Monroe’s “Bluegrass Instrumentals” album), for example, was completely upbeat. He wanted to have it that way. In fact every other time he played it, except the time it was recorded, it was upbeats he was playing it in, and I copied the rhythm in my banjo break from what he was doing on the mandolin: and then so did the fiddle; and so when we got to the studio he said, “Well, I’m not going to do it, everybody else is doing it.” Bill stayed with Monroe for nine months, leaving just before Christmas 1963.

Soon after returning to the North, in early 1964, he did a recording session in New York City with Red Allen and Frank Wakefield for Folkways records. Once again his banjo playing was setting a new direction for everyone else to follow. Gone were the long melodic lines. In their place were syncopated chordal licks, intertwined perfectly with Scruggsy runs and short melodic fragments. Bill’s break to “New Camptown Races,” from that session, is the classic example of this homogeneous sound.

Late in 1964, Bill had his now famous meeting with Bobby Thompson. New York banjoist Steve Arkin had spent the summer touring with Bill Monroe, and in his travels had heard Thompson play his version of the melodic style. When Steve returned to New York he called Keith. “Steve said, ‘Hey you gotta meet this guy,’ and we went down (to Converse, South Carolina) and listened and hung out a little bit. Bobby was playing a lot of jazz style tunes like Allen Shelton was. He was very much into Allen Shelton. So we played some, I taped it, and then we came back up here.” From the tape Bill learned “Caravan” and a few other tunes, which he incorporated in his repertoire. This meeting ultimately resulted in a raging debate as to who influenced whom. Although a small amount of cross pollination undoubtedly occurred, it appears that Keith and Thompson developed the bulk of their styles independently of one another. “I had heard my Jim and Jesse records from past years and has learned “Border Ride” and the break to “Dixie Hoedown,” and it’s really nice. So I admit to having been influenced by Bobby and it doesn’t seem likely that he escaped some influence from me if he was listening to the Opry.”

In late 1964 Bill left the verdant hills of bluegrass for a stint with the Boston based Jim Kweskin Jug Band which at that time included Geoff and Maria Muldaur, and later, fiddle ace, Richard Greene. In their time they achieved enough popularity to perform on large rock concerts, and even had the distinction of appearing on the Johnny Carson show. “I always liked that music. I played five string for a little bit in the band when I first started. Then I realized that that really wasn’t what the band needed. I got off, and still do, on that other style to a certain extent, and at that time I just really wanted to do that. It was a very tenor-plectrum type of thing. I learned a lot of new left hand positions. It’s funny during the time of the jug band I learned a hell of a lot about chords and chord motion that I probably wouldn’t have learned if I had stayed in a straight bluegrass band. Although I didn’t play bluegrass music to any degree for something like four years there, I didn’t know anything about those other forms of music really. Maybe a little Dixieland, but not much about jug band music, blues, or electric music until then.” It was during this time that Bill began to actively pursue his interest in pedal steel guitar, a move that helped to further estrange him from the bluegrass world. “I like the voicings you can get on a steel that you can’t reach on the banjo; and it seems to me it’s the Scruggs peg game, which has been a game of mine, carried to the ‘nth’ degree. Personally, when I was with Bill Monroe I really dug hanging out in the steel guitar room, just listening to Buddy Charlton (Ernest Tubb’s steel player at the time). I thought it was a mystery to which I wanted to be initiated.”

Bill got his chance to play steel when the jug band fell apart in 1968. He soon went to work playing country-rock music with Ian and Sylvia and the Great Speckled Bird. He stayed with them for about a year and then went on to tour with Jonathan Edwards and most recently, Judy Collins.

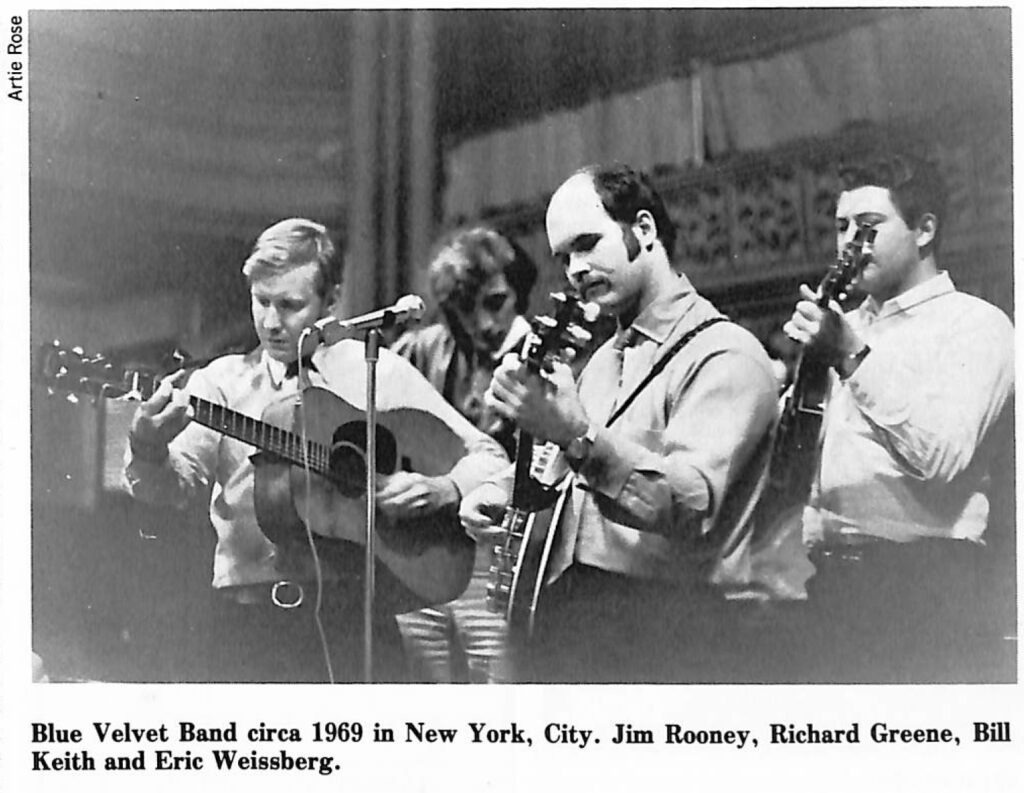

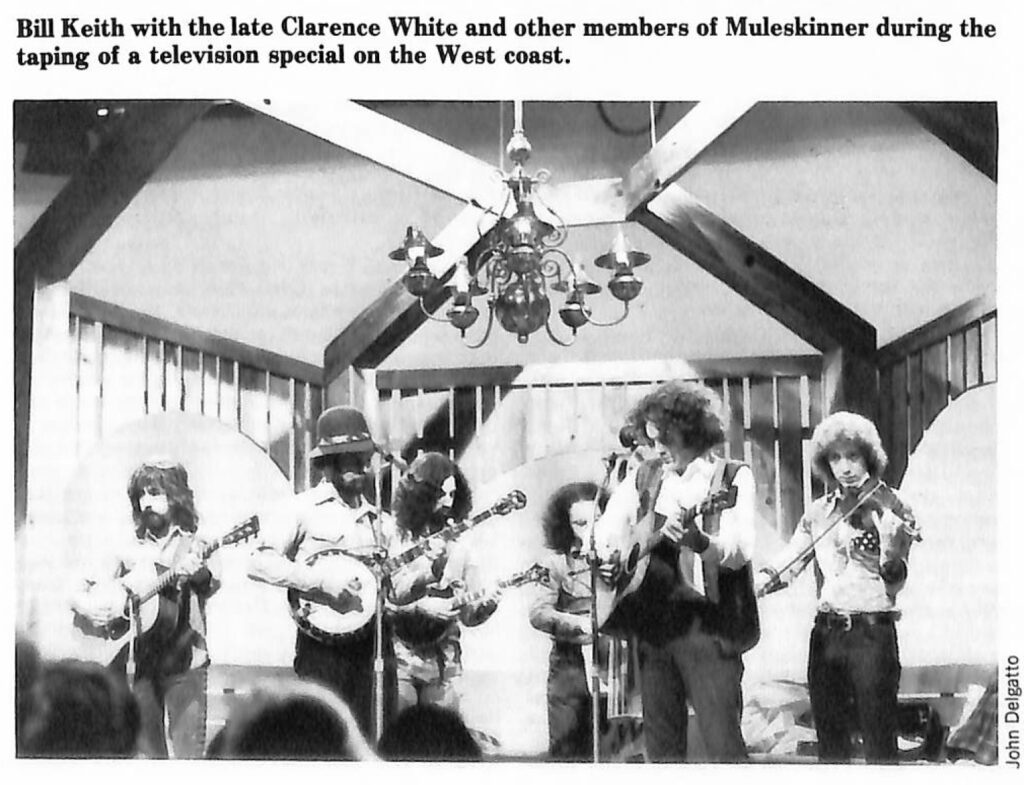

Intermittently he has surfaced in studio bands such as The Blue Velvet Band (which featured Jim Rooney, Eric Weissberg, and Richard Greene), and Muleskinner, a conglomeration of David Grisman, Clarence White, Richard Greene, and Peter Rowan. For the most part, though, Bill has stayed out of the public eye in recent years. “I haven’t been in an official bluegrass band to speak of, except for recording since I played with Bill Monroe, and nobody has offered me a job. I didn’t feel like bothering to play in a bluegrass band, and I’ve been working in other kinds of bands and enjoying that too. I’m playing steel guitar, which is some kind of burden considering the pure kilos involved, and the amps, and the whole schmeer, and the time it takes away from where else you can put music; and so does owning a house and so do other interests which are not to be denied. Durin the past two years I’ve spent more time reading than playing music.”

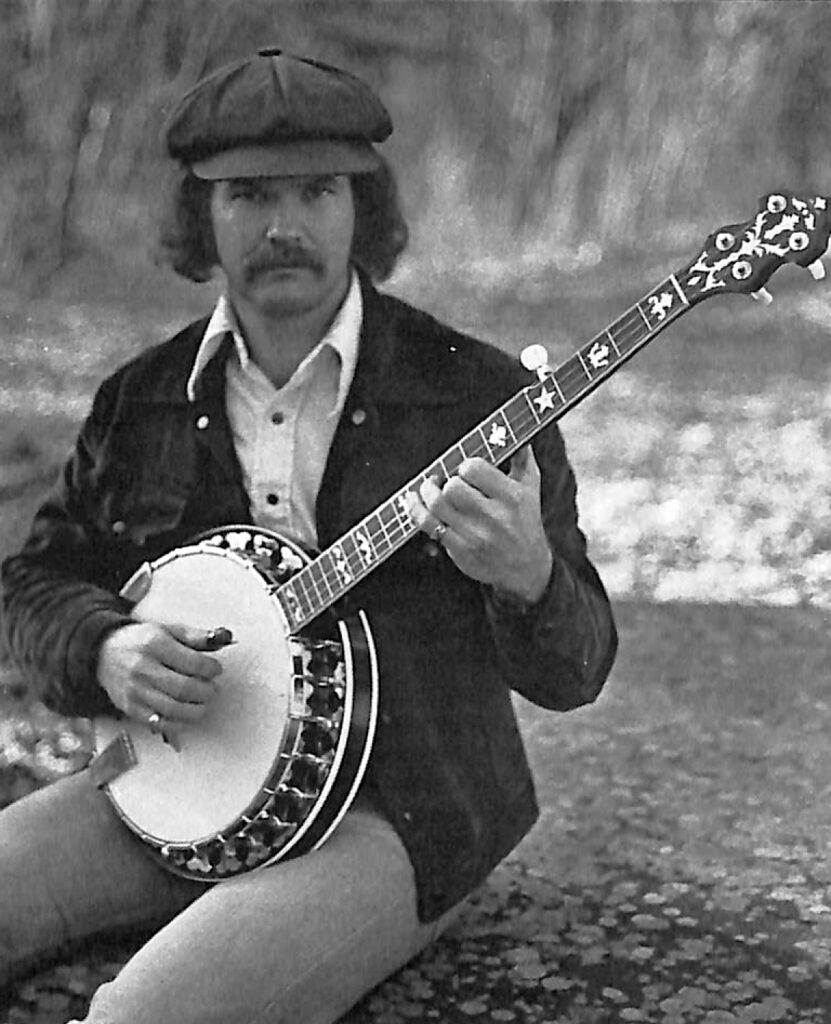

Today Bill is living in Woodstock, New York, and the reading he’s been doing covers such areas as Atlantis and psychic phenomena. Still, Bill found time earlier this year to do a small Northeast tour, playing straight ahead bluegrass with long time partner, Jim Rooney, and the younger Lilly Brothers. In addition, Bill and Jim have recently undertaken several barnstorming tours of Europe, resulting in several French recordings. Meanwhile, stateside, Bill has a solo album for Rounder records in the can. It was recorded in Washington, D.C. this past spring, and features Dave Grisman, Tony Rice, Kenny Kosek, and Tom Gray.

Except for this recent burst of bluegrass activity, however, Bill has concentrated his efforts in other musical and philosophical realms. This may seem surprising for a man who has had such a profound impact on the direction of bluegrass banjo. But as he says, “I suppose I would have played more if I’d fallen into the right situation–a bunch of bluegrass freaks, you know. It was a bunch of jug band freaks instead; and I dug that. But if something else had happened then I might never have gotten around to playing the steel and I’d still be travelling light.”

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Oh! I forgot to mention. Keith gave a banjo workshop in Rochester, NY in 1981 which I attended. I have 3 hours of his insights and it’s really fascinating. Not that I could ever reproduce what he taught us.

Hey William. You should check out http://www.KeithStyle.com

Where I explain Bill Keith’s banjo style (with videos, tabs, etc… all free). Not the pure melodic that everyone knows, but all the rest.