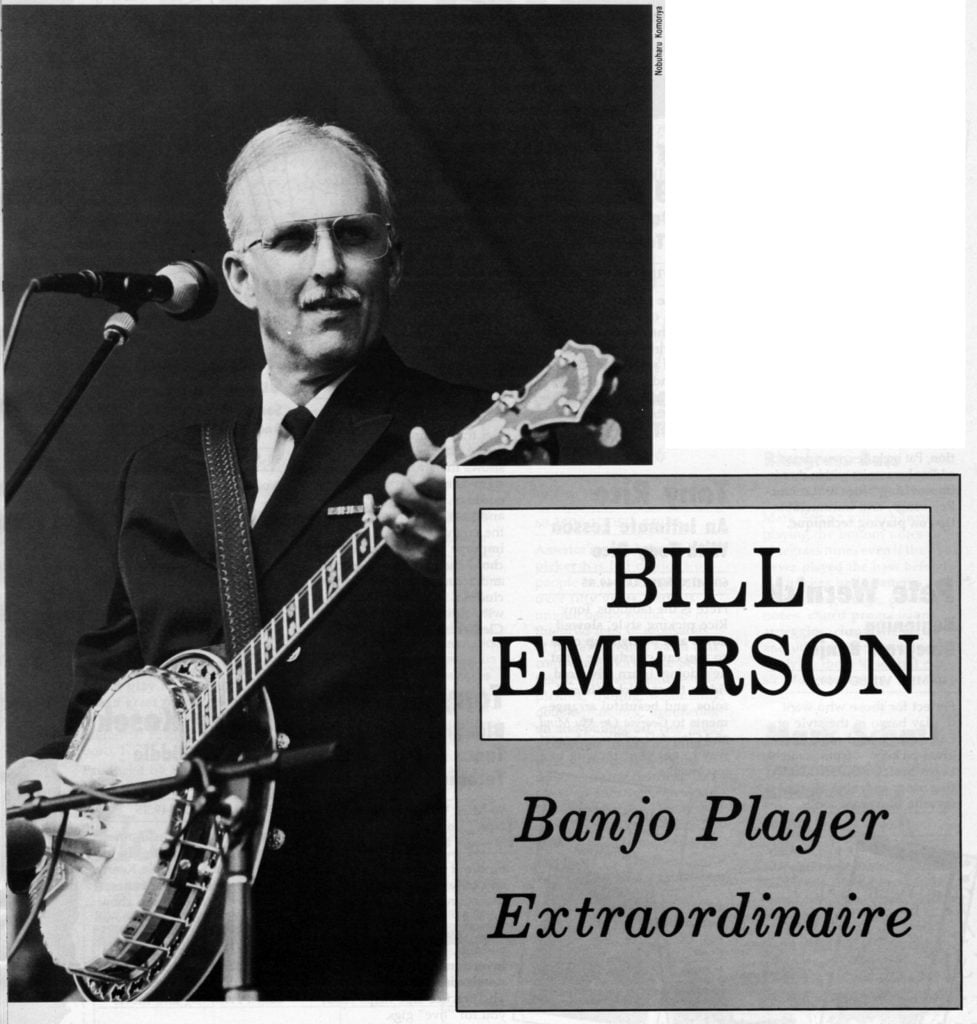

Home > Articles > The Archives > Bill Emerson: Banjo Player Extraordinaire

Bill Emerson: Banjo Player Extraordinaire

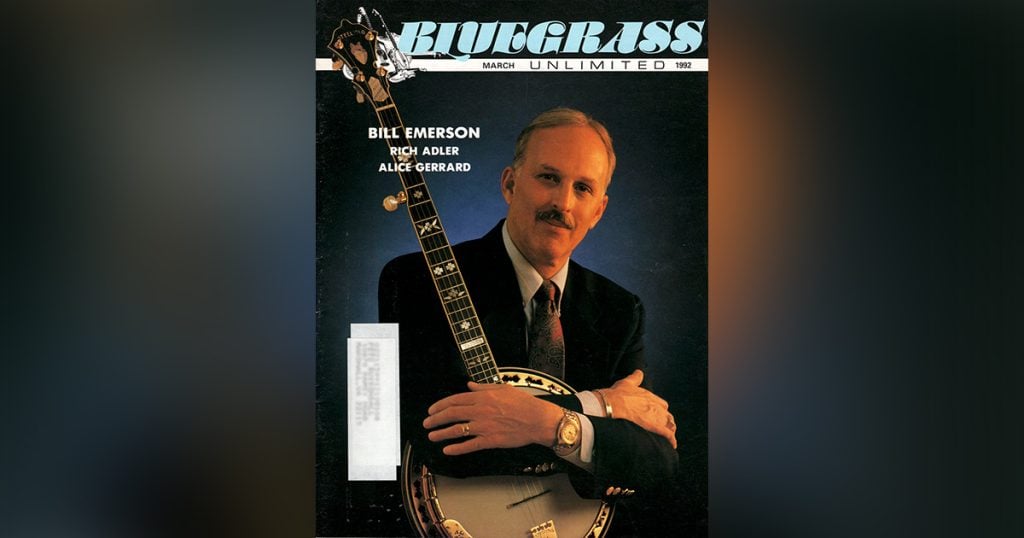

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

March 1992 Volume 26, Number 9

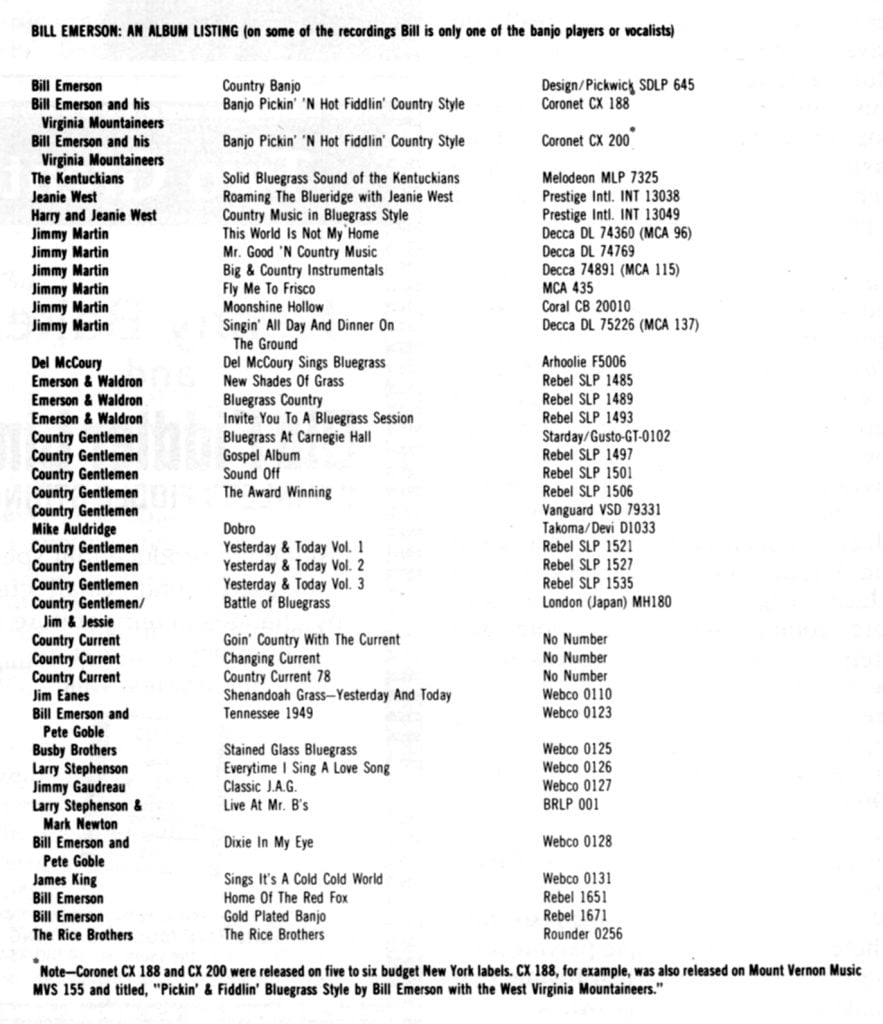

William Hundley Emerson, Jr.’s name has become synonomous with unparalleled achievement and professionalism within the world of bluegrass music. A banjo virtuoso, Bill Emerson’s artistry, ability and creativity have earned him respect from both the critics and public alike. Among his achievements, Emerson founded the Country Gentlemen on July 4, 1957 with John Duffey and Charlie Waller, spent a number of years performing with Jimmy Martin, introduced contemporary music into bluegrass with Cliff Waldron and the New Shades Of Grass and spent nearly twenty years as a U.S. Navy musician with Country Current. In recent years, he has recorded with Larry Stephenson, the Rice Brothers, Jim Eanes, Pete Goble, Jimmy Gaudreau, as well as producing two highly-acclaimed instrumental banjo albums.

Emerson’s banjo wizardry exhibits judgement, power and proficiency that only the foremost banjo-players have mastered. His competent playing is resourceful but clean. His ingenious breaks are performed with skill and finesse. And, Bill Emerson’s artistic originals, like “Theme Time,” “Sweet Dixie” and “Welcome To New York” have become bluegrass banjo standards. The interview that follows presents some insight into one of bluegrass music’s masters of the five- string banjo.

You were born on January 22, 1938 in Washington, D.C., right?

That’s right. My family lived in Virginia when I was born. I was raised in Maryland more or less and that’s where I went to school. I’ve lived back in Virginia since 1962.

How did you come to play the banjo?

I learned to play guitar before playing banjo. In listening to country music I was introduced to bluegrass. I was captivated by the banjo and figured if I could just play one tune on it. I’d be satisfied. The only records I could find were Bill Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs. I traded an electric guitar and amp for an inexpensive Belltone banjo which I later traded for a Gibson RB-100. John Duffey lived close by and he was the only person I knew who had any knowledge of a 5-string banjo. John showed me some basic rolls and chords and that’s how I got started.

Did you hear much bluegrass on the radio then?

Only a little. Mac Wiseman had a show in the morning on WBMD out of Baltimore. I’d listen while getting ready for school. His banjo player was Wayne Brown and I’d never heard of him before or since. Also, Buzz Busby had a TV show in the afternoons and I would watch him after school. Don Stover was the banjo-player. The person who helped me the most in the beginning was a local banjo player, Smitty Irvin, who eventually wound up playing with Jimmy Dean and Bill Harrell.

Where was the first live bluegrass you heard?

It was John Duffey, Bill Blackburn on banjo and a guitar player at some drag races in Manassas, Va. It was just parking lot picking. Blackburn was one of the few [banjo players] around and I only saw him a few times. But, I was able to stand right up close, watch him and was impressed with the sound of it.

Who were some of your main influences on banjo back in those days?

There were only Scruggs, Reno and Stanley. I have a lot of admiration for them. Scruggs was about as close to perfect as you can get and Reno was the most innovative. I wouldn’t say that one’s better than the other because all three have their strong points. Every once in a while I’d hear somebody else. I heard Jimmy Martin records and Sonny Osborne was playing banjo.

Didn’t you enter and win a banjo contest after playing for about three months?

Yes, at Luke Gordon’s Silver Creek Ranch [near Paris, Virginia]. First prize was a hot dog or something. I don’t know why I won, but I did. I played the “Lonesome Pine Breakdown,” one of the first tunes I could handle. I practiced every time I could get my hands on the banjo. I’d play all day and night if I could.

Have you maintained a consistent way of practicing over the years?

Not really. In the days with Jimmy Martin and the Country Gentlemen, I would practice all the time, learning new material and trying to perfect it. Lately, I’ve got a routine where I practice every day for a while until I get tired of it. Sometimes I might go for an hour, then do something else for a while and then go back and pick it up again. There have been long periods when I didn’t practice at all. It just depended on what I was doing musically at the time.

Back about 1955, you played with Uncle Bob and the Blue Ridge Partners, right?

That was my first professional job. The leader was Bob Smith. They had a radio program on WINX in Rockville, Md., about 8 o’clock on Saturday morning. I went there one day to see them and there were about ten of them with guitars, mandolins and fiddles. They didn’t have a banjo player and invited me to join the fun. They were playing local Moose lodges on Saturday nights and I got my feet wet hanging around with them.

Then, didn’t you play with Roy and Curly Irvin?

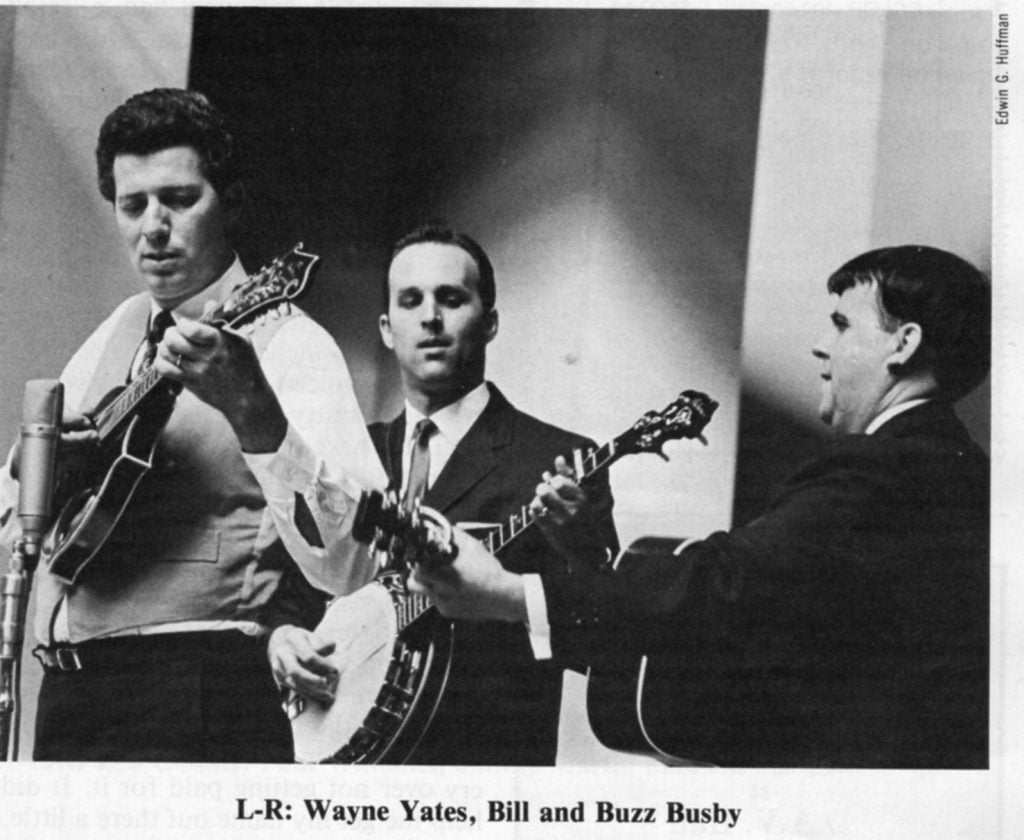

Yes, they were Smitty Irvin’s brother and dad. Art Wooten played fiddle. It was one of those jobs that got me earning money for playing at small clubs like the Pine Tavern in Washington, D.C. Then I got a job with Buzz Busby.

That was only after playing banjo for about a year, wasn ’t it?

That’s about right. I was fortunate to get with Buzz. We played in Baltimore, [Md.] at small clubs. Buzz had a radio show in Salisbury, Md. I made some records with Buzz. Songs like “Lonesome Wind,” “Goin’ Home,” “Lost” and “Me And The Jukebox.” Playing with Buzz was really my first professional job where I felt pressure to play his music, the way he wanted it. Buzz was great. He’d been playing with Scott Stoneman, Don Stover and Charlie Waller and had some excellent records out. He was a professional.”

Who were the rest of the Bayou Boys? Was Charlie Waller on guitar?

Charlie Waller at times. Pete Pike was on most of those recordings. Charlie, at the time, was back and forth between Buzz and Earl Taylor. We were all just local and the guitar player depended on who Buzz could get at the time. Vance Truell from North Carolina played bass. He also played some banjo and recorded “Whose Red Wagon” with Buzz.

How did those albums with the Virginia Mountaineers come about?

I was working for Ben Adelman, a record distributor who had a small studio in Takoma Park, Md., and recorded local artists. He stocked record racks with 99 cent albums. It was our job to sell those to stores and service them periodically. Roy Self who was playing bass for Bill Harrell, myself and Phil Flowers, a blues singer, all did that job. In the meantime, people like Bill Harrell, Buzz Busby and later Red Allen were recording for Adelman because he had a Starday connection. He’s the guy that got the Country Gentlemen the Starday deal. He asked me to record some instrumentals with various people— Buzz, Red Allen, Bill Harrell, Frank Wakefield and Tom Morgan. Out of those sessions, came about 25 instrumentals. They were put out on various New York-based budgetline labels and I never got paid anything for them. I’ve seen four or five different names on the labels and they even offered them on T.V. I’m not going to cry over not getting paid for it. It did help me get my name out there a little.

Some of the tunes were renamed, weren’t they? Like “Black Mountain Rag” was renamed ‘‘Rainbow Blues?”

Yes, they were retitled, but I didn’t do that. The studio and record companies did that, I guess, so they didn’t have to pay royalties.

Did you play some electric guitar on those albums too?

No, I don’t know who that was. Evidently, they didn’t have enough to make an album and got some electric guitar stuff somewhere. I don’t guess they got any royalties either.

How did the Country Gentlemen get formed?

Buzz, Vance Truell and Eddie Adcock were playing in a club at Bailey’s Crossroads, Va. After the gig one night they wanted to go to North Beach, Md., which was a real hopping place. I went home instead. They got in the car and hit one of those concrete bridge culverts. They were all pretty badly banged up. It broke the neck clean off Eddie’s banjo. He had them bring it into the hospital with him so he could watch it. We still had that job, so Buzz said, ‘You better get some people in there to hold it for me.’ I got Charlie Waller, John Duffey and Larry Lahey on bass. Later, we hired Carl Nelson to play fiddle. You could say I brought all of the elements together and we decided to stay together.

When did you first start singing?

When we first got together, John Duffey taught me the baritone lines. We worked hard at getting good blend and harmony. Arrangements were a joint effort. John got us a daily fifteen-minute radio program on WARL on Arlington, Va. Once a week we’d tape an hour-and-fifteen minutes worth of radio shows. That way we were able to listen to ourselves five days a week. We had a lot of fun in those days, just learning and we weren’t too serious about it.

How did the Country Gentlemen chose the material they did in those days?

We all shared in that. John wanted to do those pretty trio numbers and Charlie had his Hank Snow style. I had the straight-ahead bluegrass where I could really work on the banjo. Whatever we came up with we’d try and if it worked we’d leave it in. If it didn’t, we’d try something else. There was plenty of material available. John even got a song from Carter Stanley. It was our first record (recorded in October, 1957) called “Going To The Races.”

And ‘‘Heavenward Bound, ” on the flip side, right?

Yeah, right. I believe John wrote that and I think he recorded that with Lucky Chapman, Bill Blackburn and those guys. Or had played it with them anyway. John Hall played fiddle with us for about a year and Tom Morgan was on bass. After Tom came Jim Cox. By the time I left, Pete Kuykendall was the fiddler and he took my place on the banjo. Pete plays all the instruments and could have been a top-notch bluegrass musician had he chosen to pursue it.

What did the Country Gentlemen record for Starday at A del man’s studio?

There were several 45s. Tunes like “Bye Bye Blues” which was renamed

“Banjo In The Backwoods” or “Backwoods Blues.” The first record, of course, was on our own label. Dixie Records was the name of it.

Why did you leave the Country Gentlemen about 1958?

There were other bands I wanted to work with and I was looking for a change. After leaving, I did some Starday sessions with Bill Harrell. Songs like “Eating Out Of Your Hand,” “One Track Mind” and “I’ll Never See You Anymore.”

Didn ’t you do a few shows with Bill Clifton?

Yeah, a couple. Bill was in town doing some things and they were Don Owens’ productions. Don Owens was a DJ at WARL radio. I had worked on his TV show on WTTG in Washington. I did a couple of gigs with Bill Clifton and a few with Mac Wiseman, too.

Who were some of the others you played with after leaving the Country Gents?

I played with the Stoneman Family for about a year and a half and with Buzz Busby when he needed somebody. Red Allen and Frank Wakefield came to town and were looking for a banjo player. We did a lot of local clubs and recorded “Little Birdie” and some other tunes that came out on 45s. Red and I were associated for a number of years. He was fresh from leaving the Osborne Brothers and had a lot of professionalism. Once we played a nightclub and I was complaining that I couldn’t get anything right on the banjo. He said, ‘You know, Bill, you’re playing too loud.’ I went back the next set and eased up and didn’t have a problem at all. Those are the kind of things that Red could tell you. I’ll always consider him to be one of the greatest bluegrass lead singers.

You did some playing with Harry and Jeanie West too, right?

They were friends of Tom Morgan. They came to town to do a record and asked me to play. They’re more old- timey than bluegrass. She plays guitar and sings and he plays mandolin and sings. They do things similar to the Blue Sky Boys or Monroe Brothers.

Were you still entering banjo contests in those days?

Yes, they had a big contest in Warrenton, [Va.] called the National Champion Country Music Contest. People like Roy Clark, Billy Grammer, Buck Ryan, Scotty Stoneman all participated. I won that one in 1959. First prize was $100. They had another big one at Oak Leaf Park in Luray, Va., in 1960. At that time, Earl Scruggs was endorsing Vega banjos and they had an Earl Scruggs style banjo as first prize. It was the first of that model banjo off the assembly line and the one Earl had on The Price Is Right TV show. The TV contestants had to guess how much it cost. I won it and played it for several years.

Was it 1961 or ’62 when you replaced J.D. Crowe in Jimmy Martin’s band?

It was early in 1961. Paul Craft was working with him after J.D. had left. Paul got the mumps and they had a job in Patterson, N.J. Jimmy called and said. ‘I need you to work with me.’ I met him on the Pennsylvania Turnpike and we went to a motel room and ran through the tunes for his show. I already knew most of his stuff because I had been thinking about the possibility of working for him. Afterwards, he said Paul Craft was planning to leave and offered me a job. I accepted and stayed with Jimmy about five years all together.

That must’ve been fun!

It was a lot of fun and that was my education right there. Just about everything I’ve used down through the years I learned from Jimmy. He’s a master and right off the bat I could see the value of what I was getting from him.

What were some of the specific things he taught you while you were playing with him?

Well, Jimmy wanted you to fit with what he was doing. He never said to me, ‘I want you to play it like J.D.’ But, he would say things like, ‘Instead of hitting just one string I want you to reach down and grab a whole handful to make it sound full. Keep the tone of that banjo in there all the time.’ He showed me how to keep my banjo pointed at the microphone and how to work in and out. Jimmy didn’t play the banjo himself, but he could two-finger it just enough to show you what he wanted. You know, Earl Scruggs said the most important thing to him is how he gets in and out of a break. Jimmy taught me that was very important. Jimmy would say, ‘Hit those pick-up notes just like a fiddle would and keep them separated. You don’t want one string loud and the next not loud enough.’ He showed me how to put the emphasis, rhythm and dynamics into my playing and singing. He also taught me about show business in general. There wasn’t any part of it that Jimmy didn’t instruct me on.

Where did you play with Jimmy? Did you do some of the big radio barn dance shows?

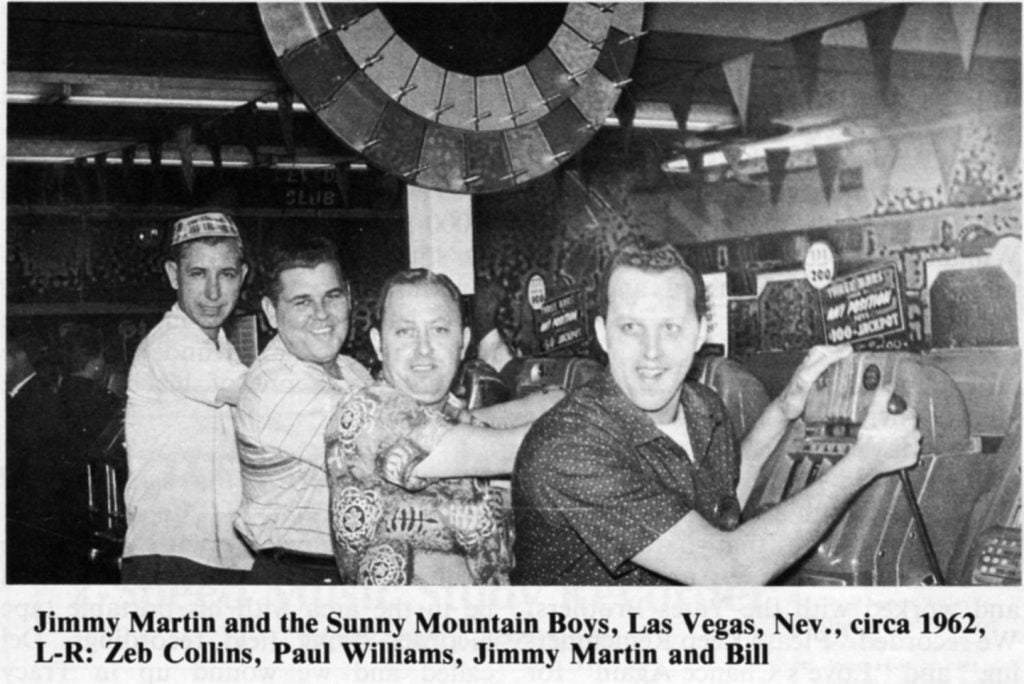

We did the Grand Ole Opry four or five times as a guest. We did go down a couple of times as a guest on the Louisiana Hayride. We were regulars on the World’s original WWVA Jamboree out of Wheeling, W.Va. Shortly after I went with him, we did a week at the Golden Nugget in Las Vegas. We did a USO thing for the troops in Newfoundland. We also played in every country music park and nook and cranny that Jimmy could get us into.

In 1968 you wrote an article for BU called “On The Road With Jimmy Martin,” you mention that you did a lot of “jungleing” while travelling.

Yeah, right. Instead of stopping at restaurants to eat, we jungled. That’s bologna, cheese, bread, mayonnaise, mustard, tomatoes and those little paper salt and pepper shakers you buy. We’d find a picnic table somewhere by the side of the road and have a great time. You know, we’d play Friday and Saturday nights at the Jamboree, go upstairs to the WWVA studios and broadcast a live show. By the time that was over, it was about 11:30 p.m. We’d load the car and away we’d go. We wouldn’t get back to Wheeling until the next Friday. We travelled all over the country like that all year long.

It must’ve been a little tiring!

I wouldn’t want to do it again, but I wouldn’t take a million dollars for the experience. There was no bus, just Jimmy’s Cadillac. The bass would go on top. Sometimes we didn’t have a bass player. It was just me, Jimmy and Paul Williams. I’d been with Jimmy about a year before Kirk Hansard and Lois Johnson came along.

How about Zeb Collins?

He was there when I got there and left before Kirk and Lois came permanently. Lois could play bass and so could Kirk. And, both could play a snare drum. Jimmy likes that snare drum in there. I left Jimmy for about a year and worked with the Yates Brothers. We recorded “Please Keep Remembering” and “Love’s Chance Again” for Tom Reeder’s Kash label. I went back to Jimmy’s band in late 1964. It was me, Bill Yates on bass, Vernon Derrick was the fiddle player and Bill Torbert played mandolin. Earl Taylor was with Jimmy for a while during this time.

Tell me that story I’ve heard about Jimmy Martin chasing a groundhog.

Coming back to D.C. to get my furniture we were up on top of a mountain. A big long grade. Jimmy saw a groundhog in the road, slams on his brakes, gets out and pulls this billy club from under the seat of his Cadillac. He ran over there towards that groundhog. When he caught up to it, it turned around and rared up at him. Well, ol’ Jimmy just gave it a swat with that billy club. In the meantime, his car was rolling down the mountain so I had to run and catch it. If I hadn’t seen it, it would have been gone. The funny part about it is that later on Jimmy had to get gas. He asked the gas station attendant, ‘Hey do you eat groundhog?’ and the guy said ‘Well, I do sometimes.’ And, Jimmy said, ‘Hey, I got this groundhog in the trunk. How ’bout tradin’ it for the gas?’ When he pulled that groundhog out of the trunk it had gotten stiff and dried up. Jimmy had to pay for the gas.

Is that the only time you’ve ever seen him chase groundhogs?

Well, Jimmy’s an outdoors guy. He’s a big coon-hunter now. We’d do a lot of fishing and rabbit hunting and he had a bunch of beagles. They had these strip mines out by Wheeling and we’d ride through those strip mines looking for groundhogs to shoot. I think if Jimmy couldn’t have shot them, he would’ve got out and chased them down.

Jimmy Martin is quite a guy isn’t he?

Yes, he is. Jimmy deserves more recognition. Look at what he’s done for bluegrass. Jimmy’s an intense individual and believes in himself. I’ve been with him on stage and he’s had 5,000 people in the palm of his hand. He’s just that kind of entertainer. Jimmy knows the business inside and out. He’s had some great musicians like J.D. Crowe, Alan Munde and Doyle Lawson come out of his bands. He helped us all.

What’s the story on the record you did with Del McCoury?

Chris Strachwitz, with Arhoolie Records, contacted Del and said he’d be in the area with his portable tape recorder doing field recordings. Del called and we wound up in Tracy Schwarz’s farmhouse up in Pennsylvania with Billy Baker on fiddle, me, Del and Wayne Yates and a bass player. We did that album in one afternoon.

What did you do after leaving Jimmy Martin in 1966?

Wayne Yates and I decided to form a band. I had been out of music and wanted to start playing again. These economic situations kept coming up so I’d have to go out and get a real job. As soon as I got back on my feet financially, I’d go back to playing music.

How did you get tied up with Cliff Waldron?

Wayne Yates, Buzz Busby and I were working together. When they left, Cliff came in as a mandolin player and then switched to guitar. Cliff and I stayed together and that’s how Emerson and Waldron came about. That was about 1967. Later, Ed Ferris, Bill Poffinberger and Mike Auldridge came into the band.

How would you explain all the interest in that band that was created?

I wanted to do something a little different. I had the idea of doing tunes like Johnny Rivers’ recording of “If I Was A Carpenter” or Manfred Mann’s tune, “Fox On The Run.” We still wanted to do some straight-ahead bluegrass music but wanted to look and sound a little different. We didn’t want to be just another straight-ahead bluegrass band. Therefore, our music attracted a wider, younger and more sophisticated audience. It paid off.

You did some Creedence Clearwater [Revival], some Merle Haggard and some Gordon Lightfoot tunes.

Exactly. We did a potpourri of stuff that wasn’t necessarily bluegrass.

In a record review by Fred Geiger, he praised you and Waldron for choosing “songs whose emotional dimensions are somewhat wider than those which explain it’s sad to have no mother or dad. ”

Yeah. That’s what we were looking for. Something that meant a little bit more. And, we were tired of singing little darling number two and the same material everyone else was doing. We wanted audiences to relate to the type of songs we were playing.

Do you think that band might have had something to do with the development of newgrass music?

Yes, I feel that way. We were doing that before anybody else. The only other band you could compare to it was the Country Gentlemen with their folk music approach. We didn’t really get into newgrass. It was more the material than the instrumental approach because I’m just not a newgrass banjo player. But, I think we paved the way to a certain extent in that the material we were doing lent itself to that kind of thing. First thing you know, the Bluegrass Alliance came along and, to me, they were the pioneer newgrass group. They were also doing songs like “Fox On The Run” and they did newgrass a lot better than we could. Nevertheless, I feel that we broke ground before them to a certain extent.

It was probably that you just created an awareness that it’s all right to do something different. Walter Hensley was doing some things along those lines wasn ’t he?

Yes, but more as an instrumentalist. He was doing pop tunes on the banjo and recorded with Boots Randolph on sax. Most of the bands he performed with were pretty well traditional. Walter is a great banjo player and it’s too bad more people haven’t heard him in the straight-ahead bluegrass context.

Mike Auldridge became a full-time Dobroist when he joined your band in 1969, right?

Yes, he did. I realized Mike’s potential and I did everything in my power to keep him in our band. He was a big selling factor and he helped take us out of the Stanley Brothers mode. We couldn’t have done it without him.

And he had a couple of originals too, of course.

Yes, he was very creative. After I went back to the Country Gentlemen, I got Mike integrated in there with them on their sessions. But, Mike didn’t want to travel on the road. I couldn’t get a Dobro on a permanent basis until I found Jerry Douglas. I felt the need to have that because you can do so much more musically with Dobro.

When did you go back to the Country Gentlemen?

I think it was the latter part of 1969. Eddie Adcock left and they needed a banjo player. Charlie Waller, Jimmy Gaudreau and Bill Yates asked me to go to Ohio with them. We’d get standing ovations and people standing up and cheering for instrumental breaks. They said, ‘Look, why don’t you just stay with us?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know, I’ve got my own band.’ So they said, ‘We’ll make this thing a four-way partnership.’ It was a good deal for me economically and it provided me with the opportunity to work with Gaudreau and Lawson later.

Gaudreau left about ’71 didn’t he, to be replaced by Doyle Lawson?

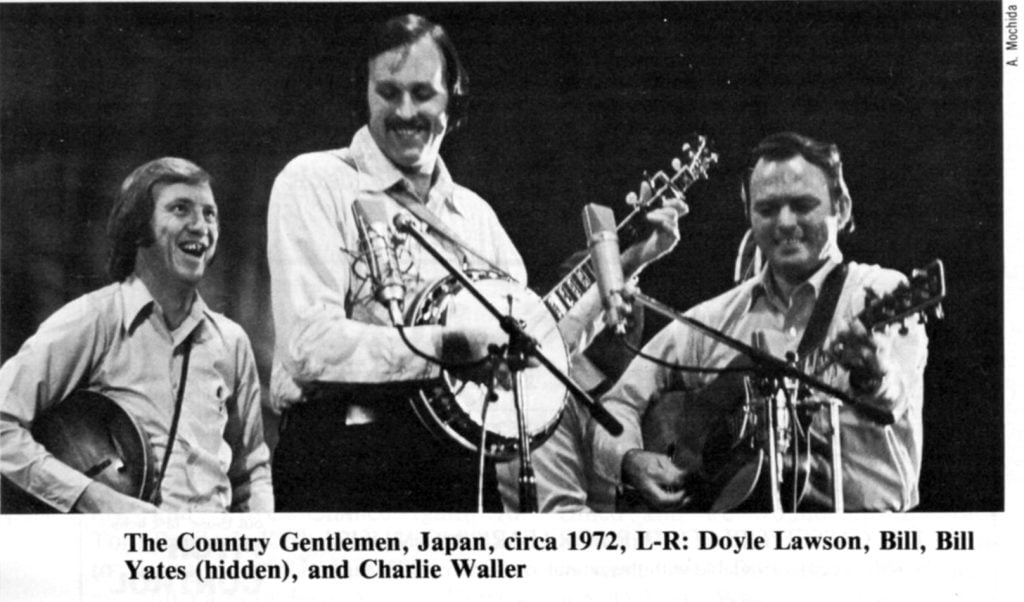

He left about a year after I went with them. Jimmy decided he wanted to do other things. Doyle was playing guitar with J.D. Crowe and we’d see him at the bluegrass festivals. Doyle and I had a lot in common in that he had played banjo and mandolin with Jimmy Martin. He was from the same [musicial] school. Doyle was ready to leave J.D. and I offered him that job. The band was at a peak at that time. We toured Japan, signed with Vanguard Records and were voted the Best Band in ’72 and ’73. Doyle was a catalyst and he and I thought a lot alike musically. We played off each other and the whole thing jelled. We came up with some good material. A lot of people think that was the best Country Gentlemen configuration. I do myself. We’ve done a reunion at Doyle’s festival in Denton, N.C., and, I tell you, we could make a great recording together.

You “rescued” Ricky Skaggs about that time didn’t you?

Yes, I had seen Ricky and Keith Whitley when they were just two little kids at a park down in Kentucky. I went out of my way to become acquainted with them because they were so good. Well, later, Ricky was living in a small apartment in Manassas and was working at the Virginia Electric Power Co. plant. I got him on the phone and managed to get him to New York to do the Vanguard album with us. He soon quit his day job and became a Country Gentleman.

When did you leave the Country Gentlemen?

I left in 1973. Jerry Douglas had just started with us. A fiddler from the Navy band came out and said they could use me. I was trying to make sure that my future was assured. After having been on the road since Lord knows when, I had a family and responsibilities. I got to thinking, ‘What will I be doing when I’m 55 years old and where will I be?’ The Navy offered me a good deal and I figured I could stay there for twenty years and when that’s over I could play music if I want to. I enlisted on May 30, 1973, right after the Ralph Stanley Festival at McClure, Va. Doyle was going in too. We both went to get the physical together. When it came right down to brass tacks at the festival, Doyle said, ‘Bill, I don’t think I can do it.’ I said, ‘Do what you gotta do, but I’m going.’ I’m glad I did. I missed bluegrass for a long time. For eight to twelve years I didn’t do much of anything. No recording. I didn’t listen to much bluegrass on the radio. I just concentrated on the Navy.

What exactly were you doing in the Navy?

I was playing in a country music configuration with steel guitar, electric guitar, electric bass and drums. The only banjo I was playing was for added flavor in the background. Maybe a break here and there, put the banjo down and play rhythm guitar and sing harmony. I concentrated on the management aspect more than the performance.

Did you do a lot of travelling?

We were on the road about 200 days a year and played for more people in the Navy than I ever would have otherwise.

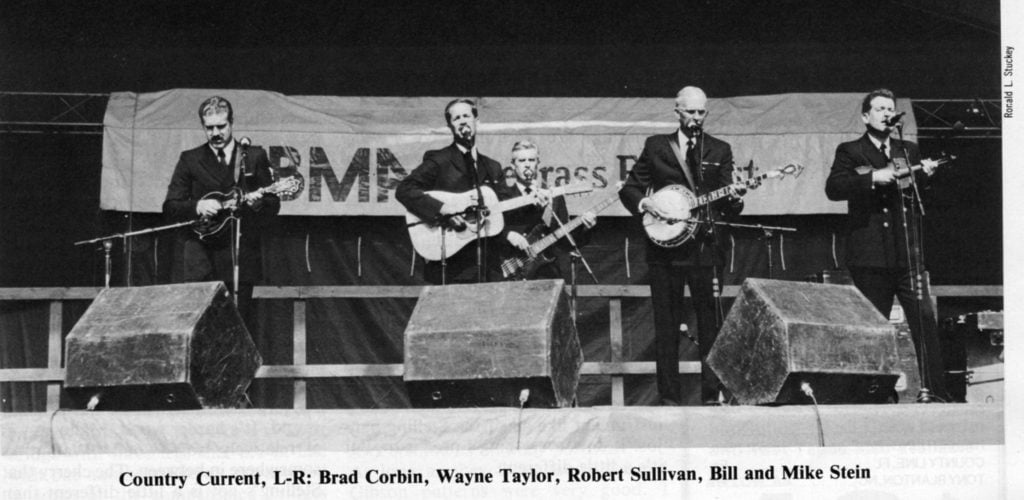

What’s the U.S. Navy’s Country Current doing now?

We still play a lot of country music, but I have a configuration that can also play bluegrass. They’re enthusiastic about learning and they’re good musicians. It’s refreshing to go to Owensboro, [Ky.] put on a bluegrass show and be well received. We play Nashville Now, the Grand Ole Opry and Opryland, Jamboree USA and about a dozen bluegrass festivals each year.

So you ‘re actually teaching your other band members a little about bluegrass music?

Not really, they are all fine professional musicians. I’ve got a mandolin player, Brad Corbin, who is a great steel guitar player. His roots are in bluegrass and his family is from Stanley, Va., out in the Blue Ridge Mountains. They are all musicians. He grew up singing gospel music in the church and plays a little banjo, guitar, mandolin and even fiddle if called on. He’s in love with the steel guitar and that’s what he’s concentrated on. Being a naturally good musician, he picked up the mandolin quickly. Shoot, now when he steps up to the microphone and takes a break he brings the house down. He gets a better hand than I do! I haven’t figured that one out yet.

And, you’ve got a good bluegrassy singer in the group now.

Yeah, he’s a great singer and can sing any style of music. He’s also a real good songwriter. His name is Wayne Taylor and he’s from North Carolina. He’s a good rhythm guitar man and a good bluegrass singer. He could sing opera if he wanted to. He’s the kind of singer they send out to do the “Star Spangled Banner” at the football game. He’s that good.

Who’s your bass player and fiddler?

I’ve got a good bass player, Robert Sullivan, who’s only been playing the standup bass for a few months, but he’s such a good musician he puts it right there. He’s actually a fine rock and roll guitar player. Mike Stein, our fiddle player, has been with me for about ten years. A terrific musician. Not exactly a bluegrass fiddler in the sense of Curly Ray Cline or somebody like that. He’s more of a swing style fiddle player, but he plays bluegrass or whatever is called for. He’s an excellent singer and songwriter as well. He’s played with Grazzmatazz, Cathy Fink, Patsy Montana and a lot of others.

I guess that being a musician in the Navy does have a lot of benefits and provides flexibility to have a band and be paid for doing what you like doing.

It’s a way to not only assure my future and give my family some security, but also a way to give something back to my country. I really feel that way. I like the professionalism and esprit de corps at the Navy band. It’s a way of life and I’ve benefitted from it.

It is illegal for Navy musicians to make personal appearances or recordings with others?

No, it’s not illegal. My attitude was, well, I’ve already done all that and I’m out of it now. It’s time to follow other pursuits. I wasn’t real interested in recording or playing bluegrass.

Does Country Current still maintain a fairly heavy road schedule?

Yes, we do. I just got off the road for 30 days. We went up through Pennsylvania, New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. We did 26 concerts and averaged 1,100 per performance.

How do you feel about some of the non-traditional directions occurring in bluegrass now? Back in 1969, you wrote that you believed that “electric instruments combined with up to date material can help bluegrass come into its own as a separate style of music. ” Do you still. . . ?

Well, I’m not against it. I don’t see why a bluegrass band shouldn’t have a piano, especially on gospel material. What bothers me is when it’s done for economic reasons, rather than for the art. I’m not against anything that will make the music sound better. I’m not against using drums. But, it depends on the band and the type of material they’re trying to do. I wouldn’t want to see Ralph Stanley with a steel guitar player. But, I don’t see anything wrong with Doyle Lawson having a piano player. What I don’t like is an electrified banjo that doesn’t sound like a banjo. I don’t mind an electric bass, but I prefer a big acoustic if I’m going to play the banjo. Whatever it is, it has to blend with the acoustic instruments.

What do you think about Pete Wernick’s phase shifter?

It doesn’t bother me. I like it. If it makes the music sound better, it’s okay with me. Pete blends it in with the overall sound and it works fine.

How did those two albums with Pete Goble come about?

Well, I was pretty stagnant and Pete is one of my friends that has stuck by me and done things for me that I really appreciate. I met him back when I was with Jimmy Martin. He’d written some songs for Jimmy. We were talking on the phone and Pete said, ‘Man, you really ought to be out there recording.’ I said, ‘You’re right. Let’s do one together.’ That’s how “Tennessee 1949” came about. The album “Dixie In My Eye” came along later. It’s too bad that Pete hasn’t done more recording. He’s a great singer and no one does his songs as well as he does.

Have you done much recording since you’ve been in the Navy?

I had done some recording for a Jim Eanes project at Wayne Busbice’s Webco studio. When it came time to get paid for the session, I said, ‘Don’t write me a check, maybe we can work something out along the lines of recording.’ About that time Pete Gobel and I were interested in doing something and that’s why we went to Webco.

What do you think are some of the biggest problems that bluegrass is faced with today and what’s needed to help it grow?

The problem with bluegrass is that there’s too much unprofessional bluegrass. It’s a type of music that anybody can play anywhere. You don’t have to have an amplifier or an AC power outlet. That’s the beauty of it, playing it just like it was played a hundred years ago. That’s not to say that anyone who’s doing it is ready to make records and compete for the jobs at the bluegrass festivals. Anyone with a few thousand dollars can produce a recording and send it to radio stations. Program directors, recording executives and promoters should be careful about who they’re putting out there to represent the bluegrass idiom. To help it grow we have to concentrate on the best music we have. The dedicated people at IBMA are doing a lot for it. We all need to support that organization. There seems to be a stigma attached to bluegrass, like the Hatfields and McCoys or Deliverance. If that was dispelled, a lot of people would come out of the closet.

What else is needed so there’s more “good” bluegrass, higher quality bluegrass and less of that unprofessional bluegrass?

We need more good professional bluegrass on the radio. The IBMA is on the right track. Radio stations need more incentive to play it. There’s something needed to get the younger crowd involved. To me, the historical aspect of bluegrass and the tie-in with Americana has awful strong value. The fact that I’m playing an American music that has historical roots in this country means a lot to me personally. Bluegrass music and the banjo as an instrument are relatively new. But then again so is our country. Maybe the historical part and better education might help improve its image.

How about your heads and bridges?

I used the Remo Weatherking for 30 years but started having problems with them. Lately, I use a double thick Saga head, a Stewart-McDonald Five-Star or a Ludwig. I buy my bridges from Curtis McPeake who has some very old maple. They have a little less ebony on top and little more maple on bottom. Other than that, they’re the same shape as the normal three-legged bridge. When I can’t get them, I use a standard Grover 5/8 bridge which I’ve been using since day one.

Sounds like those compensated bridges are kind of a good thing too.

Maybe, but they change the sound of a banjo a little bit. I just like a straight bridge with three legs that are in line with one another. There’s extra wood in some of the compensated bridges and it’s not in a straight line, so it doesn’t vibrate like a straight bridge. With a Stelling banjo, you don’t need a compensated bridge because it has the compensated nut.

How about plastic heads versus skin heads?

Well, with the old skin heads you could get a very good tone but they were extremely hard to maintain. The plastic heads are real easy to take care of, but the tone is slightly more metallic with more overtones.

How do you determine the proper tightness of the head?

It’s a not-too-tight, not-too-loose thing. Some people push on it with their thumb to see how much resistance they get. Some people try to tune the head to a certain note like an “A.” I just take my picks and tap on it to see what kind of tone I get. After 30 years, I just have an idea where it should be. That’s the best teacher, experience.

Seems like height is the important thing about tailpieces.

You don’t want all the tension on the back of the bridge. It has to be balanced with the tension on the front of the bridge. About a quarter inch off the head is right for me. I run my Stelling tailpiece back away from the bridge. It opens everything up.

Do you have a pretty high action on your banjo?

Pretty high. I don’t want rattles. It’s probably higher than most. When I saw Earl Scruggs in 1957, his action was about normal. You want to get the action to where the strings won’t buzz. Any higher won’t make the banjo sound any better. It’ll just make it harder to play.

What types of picks and capos do you use?

I have McKinney and Shubb capos. The Shubbs work great. You just keep them in your pocket. The McKinneys work great also. They’re a little slower to use, however. The tension on them is very adjustable. You can sort of cock it with your hand. If the first string is noting a little flat, you can pull the bottom of the capo towards you and put more tension on the first string. For picks, I use the old 1950s Nationals. I only have a few sets of them left and I’m always looking for them.

Any comments on inlay patterns?

As long as they look good. The old Gibson patterns were very good. I don’t know who the designer was, but he really knew his stuff. Stelling does some nice things. I particularly like his Virginian, Red Fox and Staghorn models.

What are some of the things aspiring banjo players need to concentrate on?

Understanding what they’re supposed to be playing. If I was a lead singer singing a song and the banjo player is playing the instrumental version at the same time, I’d get awfully mad at him. A banjo can add to the rhythm of a tune and tie everything together. You don’t want to interfere with anyone until it comes time to do your thing. You’ve got to be supportive. Scruggs was the most supportive banjo player I ever heard. Like Jimmy Martin said, ‘You’ve got to keep the tone of the banjo in there all the time.’ The tone has to be there, yet you have to fill the holes and take it from chord to chord without interferring with the vocalist or colliding with the other instruments.

How would you describe your own personal style?

I try to be supportive and not interfere. When It’s my time to play, I try to get into the break and out of it as good as I can, and try to stick to the melody. Not get too far out on a limb. I play it like I feel it and be creative.

Would you say your style has changed much in the last 30 years or so?

When I started out I had the same problems that a lot of young banjo players have. I heard all that banjo playing going on and I wanted to do it all in one verse. I’ve changed and know to play here or play there. There’s times the banjo doesn’t even have to play. What I’ve learned most is how to play with other people and how to make them sound better. The banjo has to be supportive.

Would you say that one hand is more important than the other?

I’m a right-hand-type of banjo player. The banjo is a rhythmic thing. I’ve always felt the right hand is important to the dynamics and timing. But you have to do something with your left hand too.

How do you stylistically build up that right hand?

By trying to fit it in with the rhythm of the guitar player that I’m playing with. I find it’s easier for me to adapt to them than it is for them to adapt to me. I feel I can really play with some people. With others, I have to adapt a little. It’s a whole different thing playing with a Charlie Waller than it is with a Tony Rice. They’re both great guitar players, but there’s two different things going on there. To play with a person you have to know them musically, know what to expect and how the feel of their rhythm is, what they’re trying to accent, where their dynamics are and support that.

I wish more guitar players in bluegrass would study their instrument and bluegrass styles to the extent that banjo and mandolin players do.

Well, you know, the lead guitar in bluegrass is a relatively new thing. Thirty years ago we didn’t have the virtuosos on guitar that we do today, but good rhythm was real important. People today need to listen to the greats and ask what they’re doing that I’m not. The timing and dynamics are everything. Rhythm is the foundation of it all.

Do you make any adjustments in your banjo, your playing style or your miking when you’re recording?

Yes, it’s a whole different thing. Microphone placement is the critical thing in recording. Everything I record is recorded flat. If I do anything to the equalization at all, I put a little bottom on it. I use two microphones, one on the head and the other down around the bottom where the flange holes are. You can get about any kind of sound you want. You also don’t want to play hard in a studio. Learning to ease up is important in any performance situation. If you’re bearing down hard all the time, you can’t create dynamics and the tone is harsh. The tape doesn’t lie.

How do you feel about the festival scene and how can they be improved?

I haven’t done that many to know. I’ve done Gettysburg, [Penna.] for three years, Bill Harrell’s festival, Doyle Lawson’s festival at Denton and a few others. They seem to be pretty well run. They’re still about the same as the ones back in the 60s and 70s I played at. The essence of any festival is the collective spirit of the people involved. There has always been a lot of camaraderie between fans and artists at bluegrass festivals.

How do you get the inspiration for some of your original tunes?

The songs come in various ways. For instance, “The Grey Ghost” on “Tennessee 1949.” I saw the title in print in an ad for some old houses. I thought the grey ghosts could be confederate soldiers. I took the first few bars of “Dixie” and built a tune on it. Other times I’ll get an idea for a little bit of a tune in my heard. Like with “Sweet Dixie.” I just built a tune on a lick. I wrote “Reynard In The Canebrakes” because it had a Stanley flavor and I wanted to do something like Ralph would do. I prefer to make my own music rather than play somebody elses’. But, you’ve got to take them as they come. You can’t sit down and write six tunes. I might go a year before I get a couple of good ideas. I put the ideas on tape and listen to them later. If they still sound good, I’ll go back and work on them.

Who is “Reynard In The Canebrakes?”

It’s tied in with the fox theme. Reynard is the proper name of the fox in folklore and fable. Canebrakes means brushy woods where the fox lives. The title of my first instrumental album, “Home Of The Red Fox,” relates to the Virginia countryside. This is a big fox hunting area. So home of the red fox means Virginia. If you’re familiar with fox hunting and that kind of lifestyle, the upscale Virginia country squire-type atmosphere, you know what I mean.

Do you have any comments about the banjo players making a name for themselves today?

The scene has changed since Peter Wernick’s and Tony Trischka’s book, Masters Of The 5-String Banjo, came out. Some of the people aren’t around anymore and there are some people that weren’t in the book who should be. There’s so many more banjo players now, it’s harder to get attention and make a name for yourself. There are many fine technicians around but being different is most important.

Ever try one of those five-string Dobros?

Back when Sonny Osborne had one I tried his. Sonny had more success with it than I could have, but I don’t think he’s using it anymore.

Sonny tried to interest you in a 6-string banjo one time didn’t he, with the low “G” string?

Yeah and Sonny is one of my all-time favorite banjo players. He’s been an idol to me for a long time. The 6-string thing and pickups with locks on the banjo, that’s just Sonny being innovative.

A pickup with locks on his banjo?

He had a pickup on his banjo back when he was endorsing Vega banjos. Vega banjos just had two resonator lugs and he had these little padlocks on there so nobody could peek inside and see what he had.

Did you ever work with Bill Monroe?

From time to time when he needed somebody. The first time, I was driving down Route U.S. 1 south near Alexandra, Va., and there was ol’ Bill in a booth making a phone call. He was trying to locate a banjo player to go up to New River Ranch with him. I walked up, introduced myself and told him I was a banjo player. That’s how I got to work with Bill Monroe the first time.

You’re the President of Webco Records now, right? What’s going on with Webco?

My son, John, runs the company. I just help out.

What kind of music is Webco looking for, just basically good bluegrass?

Wayne Busbice was the founder of Webco Records. He never made any money at it and that wasn’t his idea anyway. It was just a hobby and he wasn’t recording any top name bands. He wanted to run for the Maryland State Legislature and didn’t have time to run the record business. I was his A&R Director and we took it over. We feel like we’re helping some young artists get started. These are people we feel are the future.

Who would your all-star band include?

My all-star band to play with would be Rickie Simpkins, Jimmy Gaudreau, Jerry Douglas, Tony Rice and Mark Schatz. I do play with the configuration quite often. Tony is one of the people that is responsible for me being back in this business. He’s given me a lot of encouragement and inspiration. His level of performance is on a higher plane and he’s a quality person.

I would’ve guessed your all-star band might have included Doyle Lawson, Ricky Skaggs and Mike Auldridge.

Well, yes, I played with them years ago. I was speaking in terms of somebody new. There’s no doubt about it, though, that they are right there on the same plane. They are all extremely easy to play with. I know what they’re going to do before they do it and vice versa.

Back in the ’60s, you did some record reviews for BU and developed a system with five factors you rated the records on (music performance, vocal performance, material, record quality and overall). Any current comments about record reviewing?

I think we need to understand that the reviews are the reviewers’ personal opinions. A good review means so much to somebody who put their heart, soul, money, blood, sweat and tears into a project. If they really do have a good product and then comes along a review that’s not too good, it can really be discouraging. Sometimes not saying anything at all is better than saying something negative. One thing to bear in mind is that the popularity of a product is determined by the fans.

I understand that you were recently inducted into the Virginia Country Music Hall Of Fame and the Governor of Virginia declared a Bill Emerson day.

I was inducted on June 10, 1984 at ceremonies in Crewe, Va. As part of the tribute, Governor Charles Robb declared the date as Bill Emerson Day in honor of a lifetime devotion to bluegrass music. This honor was from the Virginia Folk Music Association which recognizes musicians and sponsors competitions to promote and preserve country and bluegrass music in Virginia. Other notable inductees are Pasty Cline, Roy Clark and the Statler Brothers. Eddie Adcock was inducted in 1987 and Tony Rice was in 1990.

Do you think bluegrass will change much by the year 2500?

Well, has it changed much so far? There’s a lot more people playing a lot more bluegrass than when I came into it. The audience has grown larger. I don’t believe prophecies of gloom and doom. Someone said recently there’s nobody left but amateurs and warhorses, but I don’t believe that. I think bands today can make a living at it. I remember the volume of product we carried with the Country Gentlemen. Some people work at it and some don’t. Jimmy Martin had us hawk the albums right on stage. When you got off the stage, you’d take an arm-load of records through the crowd and come out with money stuffed in every pocket. There’s money to be made, but you have to go get it. Nobody’s going to hand it to you.

I think bluegrass will have some young groups come along that will infuse something new into the music.

Probably so, and by the year 2500, bluegrass will still be integrated in our American musical structure. I don’t think it will ever be a big commercial success. It’s grassroots acoustic music. Until you can make the twelve-year- olds fall in love with it, it isn’t going anywhere. Who buys the records? You read about the rap records selling 30 million copies. Ten thousand copies are a big seller for a bluegrass album. I get monthly playlists from radio stations and sometimes they frustrate me. It bothers me that they’re playing a 25-year-old record from some band that’s been out of the business for fifteen years. Why are they doing that when there’s bands trying to make a living at it? My opinion is that they should be focusing more on active groups.

I guess many people dwell on the past and don’t want to accept the fact that bluegrass might be changing today.

That’s a narrow-minded attitude. If you could convince the radio stations to stick to the best stuff today, the people out there doing it and especially with heavy emphasis on the people of the future, we wouldn’t have good bands folding up because they can’t make a living at it.

What does it take to succeed in the bluegrass business?

Nobody’s making the money that artists in other idioms are making. Those that have the talent and commitment may be better off leading their own bands. That was my advice to Ricky Skaggs twenty years ago and to Doyle Lawson fifteen years ago. Larry Stephenson is doing that and is succeeding very well. It takes a lot of patience, professionalism and persistence just to become a superior musician and vocalist let alone a successful bandleader. You have to be good but different. There’s no instant gratification. Just hard work. If you have the talent and commitment, you have a chance. It’s a business and must be treated as such.

Any other comments?

People today have no idea how hard it was going through the fifties and sixties. Bands ran the road in automobiles. If the pickings are slim today, you should have seen it then. There weren’t any festivals. Bands played school-houses on percentage, roadhouses and little outdoor parks. Dedicated performers kept bluegrass going when it could have faded away. Carlton Haney just received recognition for his visionary contributions. I played the first bluegrass festival in Fincastle, Va., with Jimmy Martin in the sixties. After the festival, Carlton got us all together and talked about the future of bluegrass. I can tell you, it all happened just as he said it would. I think the younger artists who have something good need all the support we can give them, but I won’t forget the ones who paid big dues to make the music what it is.

What are the things you would like to be remembered for?

I’ve always tried to help other musicians succeed in the business, but I’ll reserve the right to answer that question later, because I’m not done yet.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Thanks much for posting this 1992 interview between Bill Emerson and Joe Ross. A lot of time and effort went into its preparation. Bill Emerson will certainly be missed by many.