Home > Articles > The Tradition > Banjo with a Bounce

Banjo with a Bounce

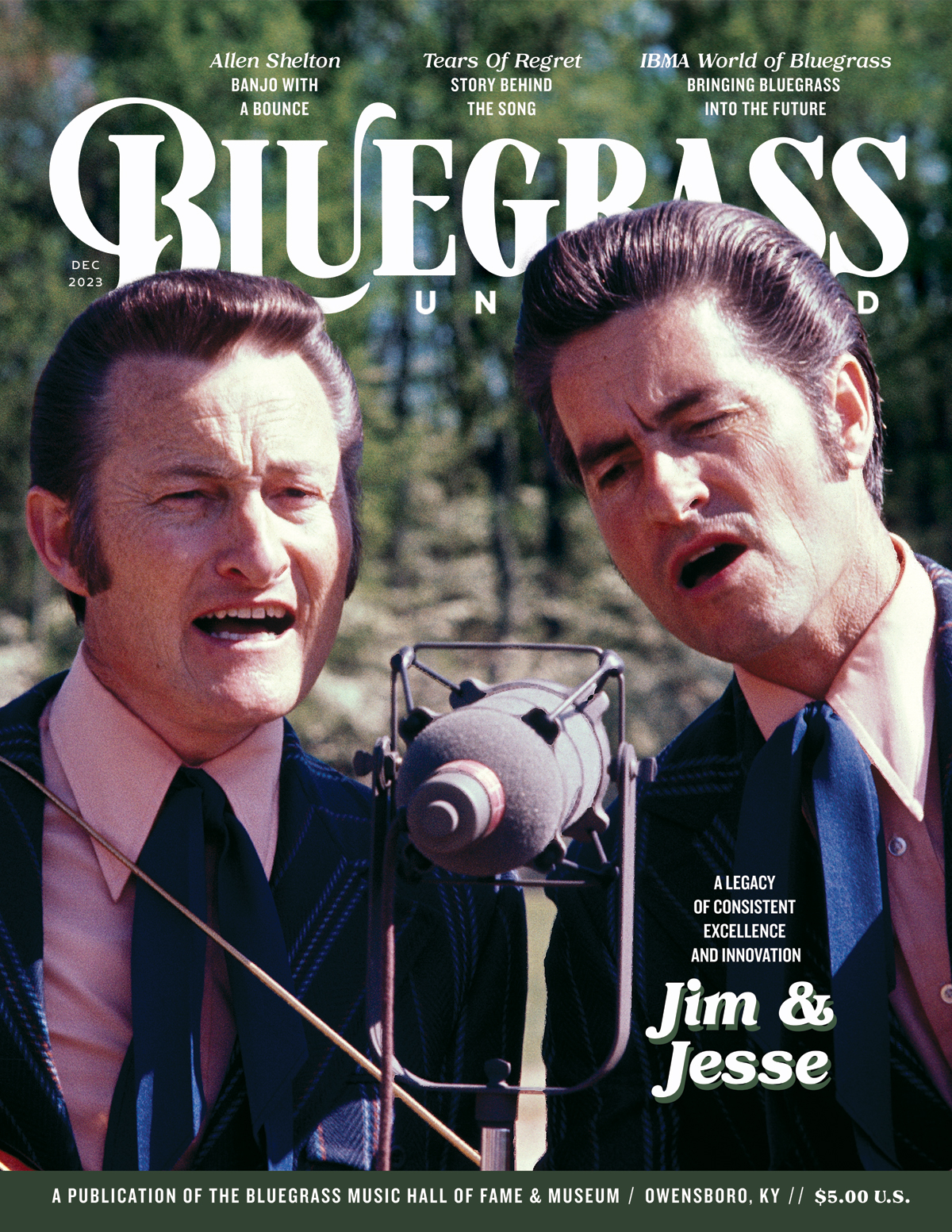

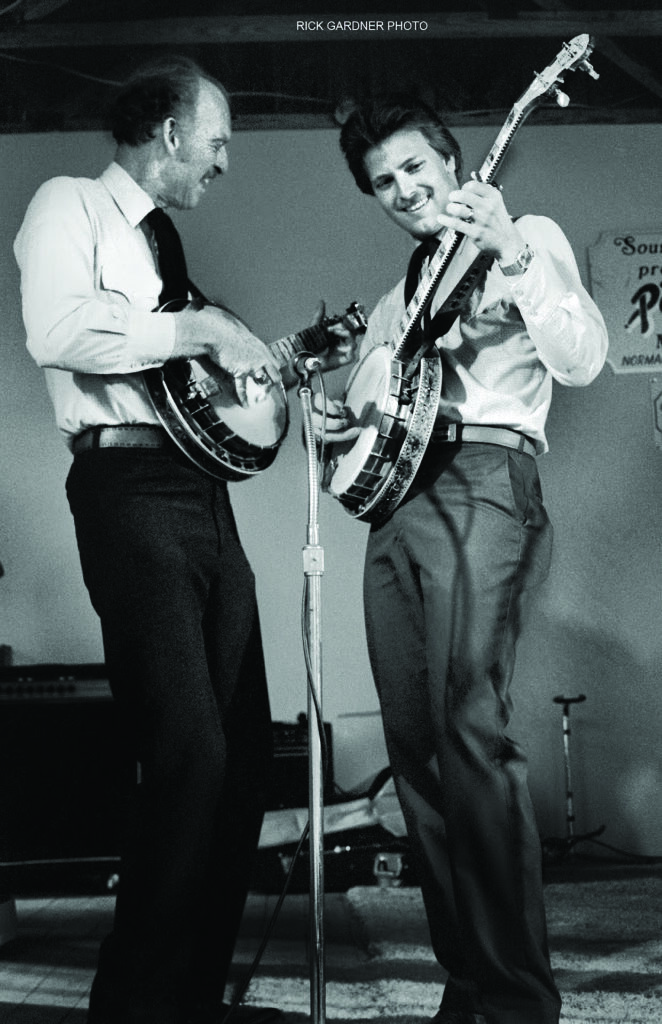

Looking back over the recordings that Jim and Jesse McReynolds made with their band the Virginia Boys, one will notice that there was no lack of talent in the banjo spot. Take a look at the list on page 34 and you will notice a number of 5-string legends. Although talent abounds on this list, the name that always pops out in my mind when I think of Jim & Jesse’s music and the banjo is the tall, thin, red-headed picker with the huge grin and bouncy banjo style—Allen Shelton.

In August of 2005 Eddie Stubbs interviewed Allen Shelton for the Bluegrass Hall of Fame and Museum’s Oral Histories Project and he opens the interview stating that in the late 1950’s someone asked Don Reno who the best banjo player was, other than himself and Earl Scruggs, and without hesitation Reno replied, “Allen Shelton.” That is high praise coming from someone of Reno’s stature, but many banjo players since that time have felt the same way.

I have my reasons why Shelton’s playing sticks out in my mind, but instead of listing the particulars regarding why I loved Allen Shelton’s playing, I’m going to leave that to the pros. Here are some comments from a few prominent banjo players regarding Shelton’s style of playing the banjo:

Alan Munde—There are many things I would say about the unique banjo playing of Allen Shelton—great timing, wonderful arched top tone, superb and neatly played ideas, a readily and easily identifiable sense of propulsion. I always looked forward to any opportunity to hear him play.

Bill Evans— It’s a rare thing to develop a unique banjo style within the boundaries of what’s appropriate for traditional bluegrass. Earl Scruggs, Don Reno, Ralph Stanley, Sonny Osborne and J. D. Crowe set the parameters early on and given the immensity of their contributions, it is a difficult thing to still create a unique identity within roll-based bluegrass banjo playing. However, Allen Shelton did just that and he did much more. We love his syncopated right hand at medium tempos (what banjo players call “bounce”) and that style was influential on many young players in the 1970’s and 80’s, myself included. However, Allen could “drive it to the wall” at faster tempos, as in his classic “Bending the Strings.”

He loved to adapt his style to pop and country tunes, such as “Whispering” and “Lady of Spain” and he composed original tunes for the banjo that are playable and catchy, such as “Shelton Special.”

Personally, he was gracious and warm and encouraging of everyone around him and as such, he was the perfect complement for both Jim and Jesse McReynolds. I believe that like-minded musicians are meant to find each other and this is certainly the case with Allen with the McReynolds brothers. We are all the better for the lifelong collaboration of these bluegrass musical giants.

Pete Wernick— I’d be quite pleased to have you use some words from me about Allen, one of my all-time favorite banjo players. I have really good memories of him, some specifically banjo-related (and some others—like about him explaining how to never ever lose a Sharpie when someone borrows it: “Keep the cap. It’ll come back!” with his trademark huge smile).

OK, about his playing: He had a strong backbeat rhythm to his playing that seemed to always be plowing forward … a rhythmically compelling drive with a sort of “hop” to it, often called the “Shelton Bounce.” There’s much discussion about what that is, some saying it’s spacing the notes so that some pairs are closer together. My theory: He really felt and accented the backbeat, with that signature hop.

Interviewing him in the mid-1980s for the Masters of the Five String Banjo book, I asked him, “What is the Shelton Bounce?” He said: “I always wonder where that came from.” When I asked him if some pairs of notes are closer together or are they spaced evenly, without hesitation he said “evenly.”

When I first saw him in 1962 (I was 16) he ended “Lady of Spain” on a C6 chord, pinky two frets up from the barred C at the 5th fret. I recognized the chord but had never seen a bluegrass banjo player use it. So I asked him about the C6 and he puzzled for a moment. Then said: “Oh, you mean the plusses.” Hmm, at first I wondered, why was he referencing an augmented 5th chord? (A chord with a + in written music means an augmented 5th chord). But to him “plus” was a catch-all term for chords with extra notes outside the 1 3 5 triad. Plusses… he said he learned them from listening to other musicians, especially pedal steel players. Among his influences were Joe Venuti and Chuck Mangione.

Always creative, in the 1950s Allen rigged up a pedal for his banjo to change the tuning, as with a pedal steel guitar. He even recorded with it, but it the experiment was short-lived.

Allen’s creative pathways often involved making pop standards into solid and appealing banjo tunes. Those included “Whispering,” “Birth of the Blues,” and “Lady of Spain” among others.

Another little-known exploration: “Crazy Banjo Medley,” released as a single in the 1950s, is a wild romp quoting parts of various instrumental tunes, with key changes, time-signature changes and a creative spark rarely seen even nowadays, but especially in the ‘50s.

Other facts worth noting: In his peak years with Jim & Jesse he always played a “bow-tie” archtop Gibson Mastertone. While most players had pre-war Gibsons, Allen was playing “only” a standard recent Gibson…and sounding as good as anyone.

Carl Jackson—At fourteen years old, it was a dream come true to stand on the stage with Jim & Jesse and kick off songs like “Standing On The Mountain,” “Air Mail Special,” and “Cotton Mill Man” or play instrumentals like “Lady Of Spain” and “Border Ride,” doing my best to fill the shoes of one of my true banjo heroes, Allen Shelton. He was one of kindest men I’ve ever met in my life, with a smile that rarely left his face at all, but never when he was playing the five string.

Allen had a unique approach and style that fit like a glove with Jim & Jesse. Their Berry Pickin’ In The Country album showcased his banjo, Jesse’s mandolin, and Jim Brock’s fiddle around a genre rarely approached with bluegrass instrumentation. The first time I heard “Johnny B. Goode,” I could almost visualize Allen “cat-walking” across the stage like Chuck Berry himself!

Jody Hughes—The first time I heard Allen Shelton on Jim and Jesse’s In The Tradition album, I was completely blown away. He had that unique, bouncy rhythm that made him instantly recognizable. I just loved the way he would accent the first string; it stayed with me. His jazzy chordal substitutions completely changed the way I approached backup. I’m still listening to him and thinking, “That’s exactly how it should sound!”

About Allen Shelton

Allen Shelton was born at home on a rural country farm in Rockingham County, North Carolina—near Reidsville. He was born on the second of July in 1936. In the interview conducted by Eddie Stubbs for the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s Oral History Project, Allen said that his father, Troy, “played about every instrument except for the fiddle.” Shelton’s father performed regularly at square dances on weekends and farmed tobacco and corn during the week on the small family farm. In an interview conducted by R. J. Kelly for Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine in 1989, Allen stated that his father’s best instrument was the guitar.

Allen’s introduction to playing music came by way of the mandolin. He learned his first chords at the age of eight or nine and shortly thereafter learned to play basic chords on the guitar.

By the time Allen was fourteen he had heard Earl Scruggs play with Bill Monroe on the radio and had also seen the band play live in Reidsville. Earl’s banjo playing inspired him to want to learn to play that instrument. A neighbor had an open-backed banjo that he played in the clawhammer style and Allen said, “I got to messing with it down at his house.” The first song that he learned how to play was “Down The Road.”

When the banjo player in Allen’s father’s dance band quit, his father decided to learn how to play the banjo and bought a resonator banjo. Allen and his father started learning to play bluegrass style banjo at the same time. Allen said, “We played entirely different. Dad played like Reno and I played like Scruggs.” In addition to learning from what he heard on the radio and in the juke boxes, a local banjo player named Junior Biggs taught Allen a few things.

Allen shared a banjo with his father for one summer. In the fall, after the tobacco crop was sold, Allen used all of the money he had earned working on the farm that summer and bought a pre-war ball bearing Gibson Mastertone banjo that had once been owned by Charlie Poole. The banjo needed work, so Allen sent it to Gibson. When he got it back the neck had a bow in it. After playing that banjo for a short while, Allen realized that the neck was not right and traded it for a Gibson RB-150 with bow-tie inlay and a raised head. This banjo did not have a tone ring, but instead had a brass rim that sat on top of the wood rim.

By the time Allen turned sixteen, in 1952, he got his first real professional job playing banjo with Jim Eanes. Although he had played some dances around Reidsville prior to joining Eanes, the job with Eanes was his first full-time professional gig. During his early career, Allen would end up playing with Eanes a couple of times. This first stint lasted about nine months. Shelton was very young, however, fiddle player Roy Russell took Allen under his wing. In the interview with Eddie Stubbs, Shelton said, “He kept me out of trouble.”

At the time Shelton joined Eanes and his band, they were playing on a radio station out of Danville, Virginia (WBTM). The band performed on the radio every day during the week at noon and then played dances on Friday and Saturday nights. Shelton moved to Danville when he joined the band and was paid $35 per week. The band also performed shows regionally. WBTM was a 5000 watt station with a range of about 100 miles. The band would tour out to the fringes of that signal.

After Shelton spent about nine months with Eanes, Mac Wiseman called and offered him a job with his band. Wiseman was at the Old Dominion Barn Dance in Richmond and was popular at the time. Shelton decided to go with Wiseman in 1953 because Mac was offering $60 a week. Shelton spent six months working with Mac Wiseman and traveled in the band’s station wagon to twenty states during that six month period.

In the Oral History interview, Allen recalls that as a young seventeen year old who had not been far away from home, he would ask Wiseman a lot of questions while they were traveling. He said, at one point Wiseman looked at him in frustration and said, “Red, I don’t know everything!” Shelton had his first studio experience while playing with Wiseman, recording seven sides, including the Wiseman hit “Love Letters In The Sand.”

When Allen left Mac Wiseman in 1954, he went to work with Hack Johnson and the Tennesseans. Roy Russell, who had performed with Jim Eanes, was with Hack and the band needed a banjo player. Hack was offering Allen the same amount of pay he received from Wiseman, but there wasn’t as much traveling involved.

Johnson’s band worked out of WPTF in Raleigh, North Carolina. They had a 5:45 slot in the morning and a 1:30 slot in the afternoon. Additionally, they would perform live at drive-in theaters in the evenings, at various music parks on the weekends, and do gospel shows at churches and tent revivals.

A tune that Shelton recorded with Hack Johnson that brought him notoriety was “Home Sweet Home,” with “You Don’t Have To Be From the Country” on the flip-side. When recording “Home Sweet Home” Shelton played in the key of D and used Scruggs-style tuners that he had installed on his banjo by an acquaintance in Burlington, North Carolina. “Home Sweet Home,” which Johnson sang, was popular on the radio and led to the band getting more work.

Another of the tunes that Allen recorded with Johnson was “Crazy Banjo Medley.” This was a medley of various banjo tunes that were strung together. In an interview that Pete Wernick conducted in 1984 with Allen for the Masters of Five String Banjo book, Allen said, “I just got the idea to put a whole lot of tunes, just parts of ‘em together, and then throw in some crazy stuff.” When Wernick asked Shelton if he gets requests to play that song live, he replied “I wouldn’t dare try it.”

It was during his time with Hack Johnson, in about 1954, that Shelton obtained the Gibson RB-250 that he played until Gibson gave him a new Granada model in the 1980s.

While Shelton was working with Hack Johnson, in 1955, the radio station fired Johnson (due to his drinking problem) but kept the band—renamed The Farm Hands. It was during this time the Shelton developed his arrangements for many pop standards, such as “Five Foot Two,” “When You Are Smiling,” “Sweet Georgia Brown,” “Bye Bye Blues,” “Lady of Spain,” “Whispering,” and others. It was The Farm Hand’s guitar player, Curly Howard, who taught him the chord changes to these tunes. The band was working two shows a day at the station and during the noon time show the station wanted the band to play that kind of music. Shelton would later record many of those songs on his solo album Shelton Special in 1977.

The Farm Hands stayed at WPTF for about another year, but the station ran into some financial trouble in 1956 and couldn’t afford to keep them at their current pay, so Shelton and Roy Russell went back to work with Jim Eanes. At that time Eanes was working at WHEE in Martinsville, Virginia. In addition to work on the radio, the band performed at dances in tobacco barns and at VFW halls four nights per week.

During this time (1956-1960) Eanes used the recording equipment at the radio station to cut records that were released by Starday. He cut 35 titles and Allen Shelton played on nearly every one of them. One of the tunes that Allen is know for, “Bending the Strings,” was written when he was with Hack Johnson, but recorded when he was with Jim Eanes. Another tune that banjo players associate with Shelton is “Lady of Spain,” which he also recorded with Eanes. The band recorded that tune, with “Long Journey Home” on the flip side, in Washinton, D.C. and it was released on Blue Ridge Records. It was a hit for Eanes.

It was during this second stint with Jim Eanes that Shelton added a pedal attachment to his banjo. He loved the sound of the pedal steel guitar and was working on a way to play banjo on Eanes’ slower numbers. He attached a device to his tailpiece (made by the same person who put the tuners on his banjo) that he could press down with his wrist. He would tune the banjo to open D and when he pressed down on the pedal with his wrist, it would stretch the second and third strings so that the banjo would be in G tuning. He kept the pedal device on his banjo for about a year.

In 1960 Jim & Jesse called and offered Allen Shelton a job playing banjo with them, replacing Bobby Thompson, who had to leave for military service. They offered Shelton more money than Eanes could pay and so he took the job. At the time Jim & Jesse were in living in Valdasta, Georgia and playing on TV in Albany, Georgia, Dothan, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida. The shows in Albany and Dothan were live on Monday and Tuesday, respectively, and then they taped the Pensacola show on Tuesday night. This schedule freed them up to perform live from Wednesday through Sunday. Jim & Jesse started Shelton out at $75 per week with a promised raise to $80 if things worked out.

In the Oral Histories interview, Eddie Stubbs observed that when Vassar Clements and Bobby Thompson were in the band things “started to jell” for Jim & Jesse. Then, when Allen Shelton and Jim Buchanan joined the band, “it came to a zenith.” Two recordings that were released in 1963 attest to Stubbs’ observation—Bluegrass Special and Bluegrass Classics. Stubbs said that these recordings are like a master class in how to make music.

During his first stint with Jim & Jesse, Shelton would be part of four more classic recordings—Old Country Church (1964), Y’all Come (1965), Berry Pickin’ In The Country (1965), and Sing Up To Him A New Song (1966). Shelton was also a member of the band when Jim & Jesse became members of the Grand Ole Opry in 1964 and took over the morning show on WSM that Flatt & Scruggs had occupied. Shelton and the rest of the band moved from Prattville, Alabama to Nashville, Tennessee after Jim & Jesse joined the Opry.

By 1966, Shelton decided that he needed to bring in more money than playing music for a living was able to provide. In an interview for the 1989 Bluegrass Unlimited article, Shelton said, “At that time there wasn’t a lot of money in bluegrass music. You could dig a living out, but I had four kids. They all wanted to go to college—and I saw the five-string wasn’t going to send them.” Shelton left the music business and first worked as a machinist in Lebanon, Tennessee for a couple of years. Then he moved to New Orleans and became a journeyman pipefitter and welder. While he was in New Orleans, from 1968 to 1975, he played in a country dance band called The Dixie Revelers, however, the instrument he played in that band was a five-string Dobro that he found in a pawn shop in Baton Rouge.

In 1975, Shelton moved back to Tennessee and worked for Dupont in Madison, Tennessee. The Bluegrass Unlimited article states that he worked as a pipefitter and welder at nuclear power plants in the Tennessee Valley area. During this period of time Shelton was not playing much music. He did occasionally go out with the McCormick Brothers when Haskel McCormick couldn’t make a show and he did record his solo album Shelton Special in 1977 for Rounder.

When the power plant work started to dry up because power plant construction was slowing down, Shelton spoke to Jesse McReynolds, in 1983, and asked if he needed a bus driver. Mike Scott was the banjo player in the band at the time, so his old slot was full. But, how can you have Allen Shelton on the road and not put him on stage!

Mike Scott remembers, “For the first few weeks Allen was driving only and not performing. Then, after a few trips, Jesse asked him to bring his banjo. We were driving down I-81 after a show and Jesse was behind the wheel. Allen and I started playing twin banjos. His lead was so solid, clean and precise that I could hear the harmony. I had listened to his recordings my whole life and he was playing the tunes the same way. Jesse was saying ‘Try this’ and named a tune. That got them thinking about us playing twin banjos during the show.” At first, they would bring Allen out for a couple of numbers playing twin banjos with Mike. Later, Allen brought out the 5-string Dobro and played the whole show on that instrument, in addition to the twin banjo pieces.

Mike Scott added that he would sit next to Shelton while Allen was driving the bus and talk music for hours. Scott said, “I had studied all of his stuff. His transitions when playing back up, his phrasing, his dynamics…his tone. He knew when to play and when not to play. He played straight, clean and solid. He made every note count. He was a great guy. We spent a lot of time telling stories and laughing. To me, it was a priceless experience.”

When Mike Scott left the band in 1987, Jim & Jesse decided to move Shelton over to banjo and hire Glen Duncan to play fiddle. Regarding his work with Shelton, Glen Duncan said, “Allen Shelton was so great to play music with because his timing was absolutely perfect! Every single time, every single song, from beginning to end, perfect!! Allen’s feel for how to play banjo in a band was the backbone of the Jim & Jesse sound. Always innovative, always creative, and Allen always played the melody of the song with drive and style.”

In the interview with Eddie Stubbs, Shelton was equally complementary of Glen Duncan, saying that Glen could play fiddle just like Vassar Clements or Jim Buchanan had done on the old Jim & Jesse albums and could play “Bending the Strings” just like Roy Russell.

Allen Shelton left Jim & Jesse in 1989 and took up a maintenance job until he retired from that at age 65 (about 2001). After Jim McReynolds passed away in 2002, Shelton occasionally took the banjo out again to perform with Jesse. In 2009 Shelton was diagnosed with leukemia and passed away on November 21st, 2009. Allen Shelton was inducted into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame in 2018.

For more information about Allen Shelton, please view the Oral Histories interview conducted by Eddie Stubbs. It is a three-hour long interview with Shelton conducted in 2005. Allen tells great stories and you get to hear his infectious laugh and see his big grin while he tells them. It is worth the time spent if you are a Allen Shelton fan: https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt7pvm42vd17