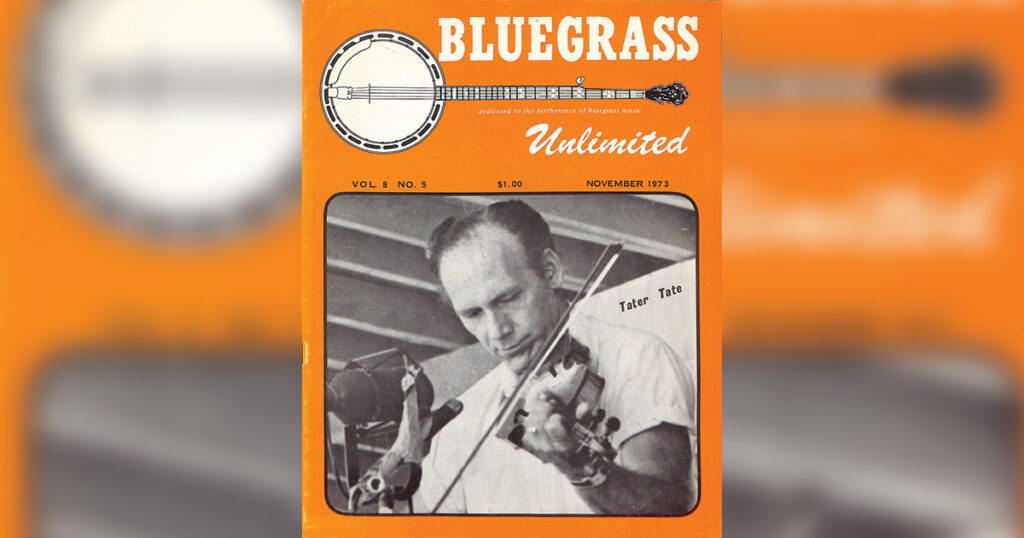

Home > Articles > The Archives > A Quarter Century of Bluegrass Fiddling — Clarence “Tater” Tate

A Quarter Century of Bluegrass Fiddling — Clarence “Tater” Tate

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1973, Volume 8, Number 5

Among bluegrass musicians, fiddlers have frequently achieved special attention. At a number of festivals in recent years fiddlers such as Tex Logan, Chubby Wise or Howdy Forrester make guest appearances and occasionally several fiddlers perform at once on stage. Not even the banjo — bluegrass music’s most distinctive instrument — is thusly featured. The prominent place accorded the fiddler may be considered all the more unusual when one recalls that many bands do not even have one.

Bluegrass music was never short of outstanding fiddlers. From the early days when Art Wooten, Benny Martin, and Leslie Keith served as outstanding sidemen to more recent times when Kenny Baker, Curly Ray Cline and Byron Berline have been widely acclaimed, men who adeptly play the “country violin” have never really been scarce. However, if one were to ask what bluegrass fiddler had recorded most frequently and played most consistently, the name of ‘Tater’ Tate might likely be considered. In fact, Tater is now beginning his second quarter century as a bluegrass fiddler which is no mean accomplishment for a man who is only forty-two.

Like numerous other bluegrass artists, Clarence E. Tate came from a musical family and a musical area. As the youngest in a family of nine — six of whom played instruments — and as a native of southwest Virginia, Gate City in Scott County, young Tate received a steady diet of music from the time of his birth on February 4, 1931. By the age of four he was showing interest in the guitar and a year later made his radio debut.

At the time the older members of the Tate family were performing on WKPT in Kingsport, Tennessee, as the Cumberland Mountaineers, young Clarence received his first professional experience with the group playing guitar and also ukelele, an instrument perhaps more attune to his physical size in those years. His early performances were limited to local activities — the radio, a Saturday night barn dance in Kingsport, and also for a time, the Saturday morning “Barrel O’Fun” show on an Elizabethton, Tennessee station. However, as the older members of the family grew up, they lost interest in playing music professionally, and the Cumberland Mountaineers ceased to exist.

Clarence continued to take an interest in music and added the mandolin to the list of instruments he played. He worked on the family farm and at a sawmill, but by age sixteen he was ready to leave home for a musical career. In 1947, he teamed up with the Moore Brothers of Nickelsville, Virginia and they went to Knoxville and WNOX’s Mid-day Merry Go Round. In less than three weeks, however, he was back home as the Moore Brothers had not especially found the city to their liking.

Returning home and to the job at his uncle’s sawmill, Clarence soon came under the influence of Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys who were just beginning their career at WCYB Bristol’s “Farm and Fun Time.” Jimmy Shumate played fiddle with this early version of the Foggy Mountain Boys and his styling appealed to young Tate who then took up that instrument and it has been his principal interest to this day.

Nineteen forty-eight, the year that saw the launching of the Foggy Mountain Boys, was perhaps the key date in the musical development of Clarence Tate. In Kingsport, he helped form a country group named the Ridge Runners which also included Jim Smith, who played many years with Carl Smith, and the Haynes Brothers, Walter and Jack. While playing on the “Broad Street Furniture Show” on WKPT in Kingsport, the Ridge Runners were hired by Archie Campbell, the well-known singer-comedian of Knoxville to help entertain at political rallies for Roy Acuff’s gubernatorial campaign in the east Tennessee region.

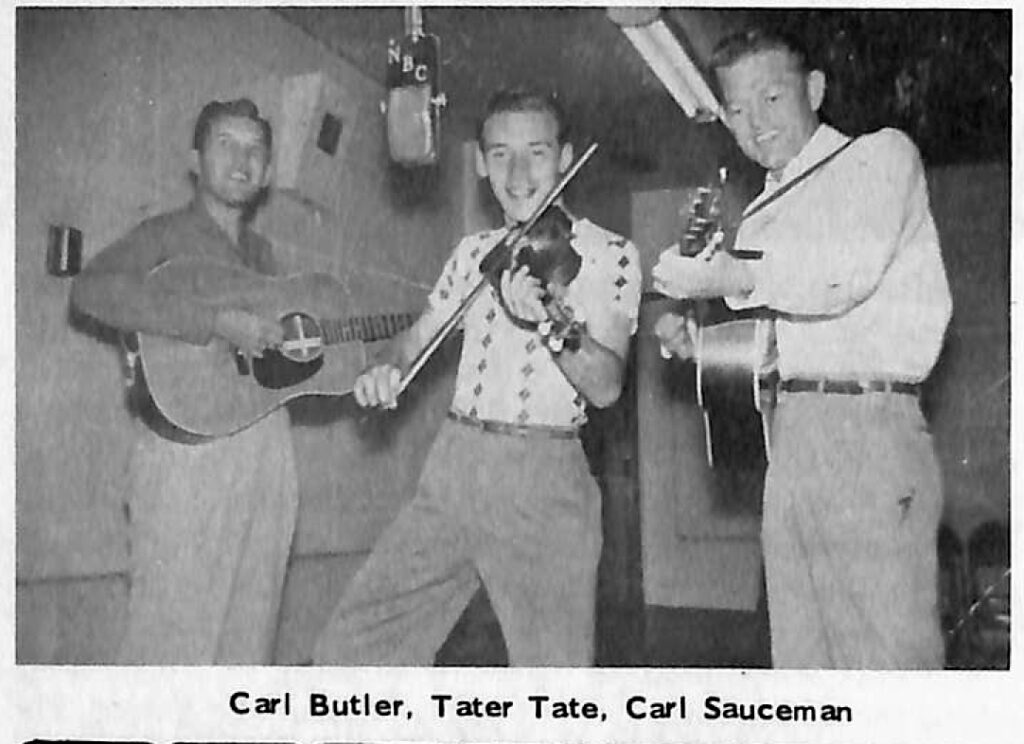

The year or so Clarence Tate spent with Archie Campbell might be considered as the equivalent to a college education in the field of country and bluegrass music. The Knoxville of the late 1940’s was literally swarming with both experienced and up-and-coming musicians including Carl Smith, Carl Butler, Joe Stuart, Bill and Cliff Carlisle, Archie Campbell, Johnnie Whisnant, Carl Sauceman and Clarence Tate among others. The Mid-day Merry Go Round, Cas Walker (a local supermarket owner who for many years has sponsored radio and TV programs featuring traditional bluegrass music) shows and Tennessee Barn Dance provided outlets where such musicians could display their talents and where frequent contact with each other provided opportunities to trade songs, ideas, styles, licks and general musical knowledge. It was also in Knoxville during this period that Clarence Tate received from Cas Walker, the nickname, “Tater,” that has become a household word among bluegrass fans the world over. In Tater’s opinion, the period, 1948-1950, that he spent in Knoxville was of tremendous value in terms of the musical experience he gained.

Archie Campbell’s Dinner Bell show on WROL included a number of acts like that of the Sauceman Brothers with whom Tater played fiddle along with Wiley Birchfield on banjo. This was Tater’s first exclusive experience in bluegrass music and when Carl and J.P. moved to Bristol’s Farm and Fun Time in 1950, he went with them. It was during their stay at WCYB that Tater played in his first recording session on the Rich-R-Tone label. He recalls playing on “I’ll Be No Stranger There”/ “Hallelujah, We Shall Rise” (Rich-R-Tone 701) and perhaps also “Little Birdie”/ “Pretty Polly” (Rich-R-Tone 457).

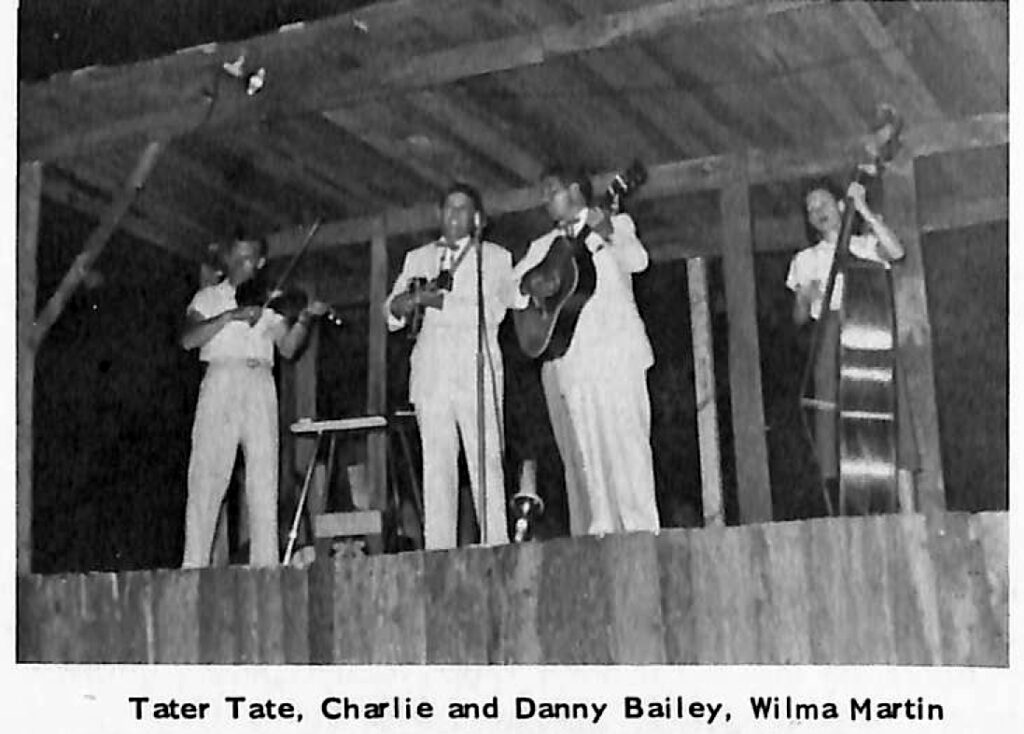

In late 1950, Tater joined the Happy Valley Boys band of the Bailey Brothers which also included Hoke Jenkins and E.P. “Jake” Tullock. The Baileys were at WPTF in Raleigh at the time and very popular. In December, 1951, the Baileys moved on the Roanoke’s WDBJ and Tater worked with them there briefly before being drafted into the Marine Corps. By June, he was discharged and back with the Baileys who had moved on to WWVA and the Wheeling Jamboree.

Things went well at WWVA and the Baileys were very successful playing to packed houses through Pennsylvania, New York, New England and on into eastern Canada. Then Danny Bailey became ill and returned to Tennessee. Charlie Bailey soon got a new group together and Tate played with him until June, 1954, when he was again drafted, this time into the Army. At the time he was called back into the service, Tater had been playing with Charlie at a radio station in Moncton, New Brunswick.

The Army kept Tater away from professional bluegrass for two years but not away from the fiddle. Much of his service was spent in the Panama Canal Zone where he organized a band that played in various NCO clubs.

When Tater Tate came out of the Army in 1956, he planned to go into another line of work and retire from music. However, his period of retirement was short as he got a call from Joe Stuart on behalf of Bill Monroe who was searching for fiddler to replace Bobby Hicks who had received a draft call. Tater finally agreed to join the Blue Grass Boys and played his first show with them at Sunset Park in West Grove, Pennsylvania. This occurred during Monroe’s so-called “low period” when bluegrass and hard country music suffered badly from the competition of rock-a-billy and rock-and-roll. In addition to Tater, the band at that time included Bessie Mauldin, Jackie Phelps and Joe Stuart. After a couple of months, Tater suffered a series of severe migraine headache attacks (a problem that still recurs periodically) and he was forced to quit. Following a period of recuperation. Tater rejoined the Bailey Brothers during their brief reunion in Knoxville.

While doing this last sojourn with the Baileys, Tater also began to work some with Carl Story and the Brewster Brothers. During this period, Tater cut some sessions with Carl on Mercury including cuts of “Mocking Banjo” and “Light at the River.” A couple of years of this activity in Knoxville and Tater again retired briefly from the music business. He moved to Chicago and went to work in a steel mill. While in Chicago, Tater continued to stay in practice by fiddling with local groups in clubs.

Lester Flatt, however, put a sudden end to Tater’s career as an industrial worker when he asked him to become fiddler for the second unit of the Martha White Show to be headed by Hylo Brown. Tater joined the Timberliners and thus became a member of one of the best bluegrass bands ever assembled. Hylo’s group also included Red Rector on mandolin, Jim Smoak on banjo and Joe Philips on bass. For a time they worked TV shows in Jackson, Tennessee and Jackson and Tupelo, Mississippi. Numerous personal appearances and the Louisiana Hayride kept the group quite busy. After a year or so they traded places with Flatt and Scruggs and worked on the eastern circuit which included TV shows in Chattanooga, Knoxville, Bluefield, Huntington and Clarksburg plus working on the Wheeling (WWVA) Jamboree. Tater played fiddle on the classic Hylo Brown Capitol T 1168 album and also some singles with Brown. After a while the TV shows were discontinued except in Huntington and Clarksburg. But the Timberliners continued to work there and at WWVA. Finally, family illness forced Tater to quit and return to the Gate City, Virginia area.

Back home, Tater joined the Bonnie Lou and Buster Moore TV show in nearby Johnson City. An early morning TV format which provided regular work with limited travel, was a situation which held considerable appeal for a sideman who did not enjoy rigorous road schedules. During this period Tater helped the Moores cut one album on the Do-Re-Mi label in Nashville.

Nineteen sixty-three had Tater working briefly for two groups. For a few months, he went south and rejoined his old friend, Carl Sauceman in Carrollton, Alabama. However, this reunion was short-lived because Tater was stricken by renewed attacks of the migraine headaches that had plagued him during his work as a Blue Grass Boy in 1956.

After recuperating he worked for a short period in September with Jimmy Martin and the Sunny Mountain Boys. He fiddled on one record session, that which produced the hit song, “Widow Maker.”

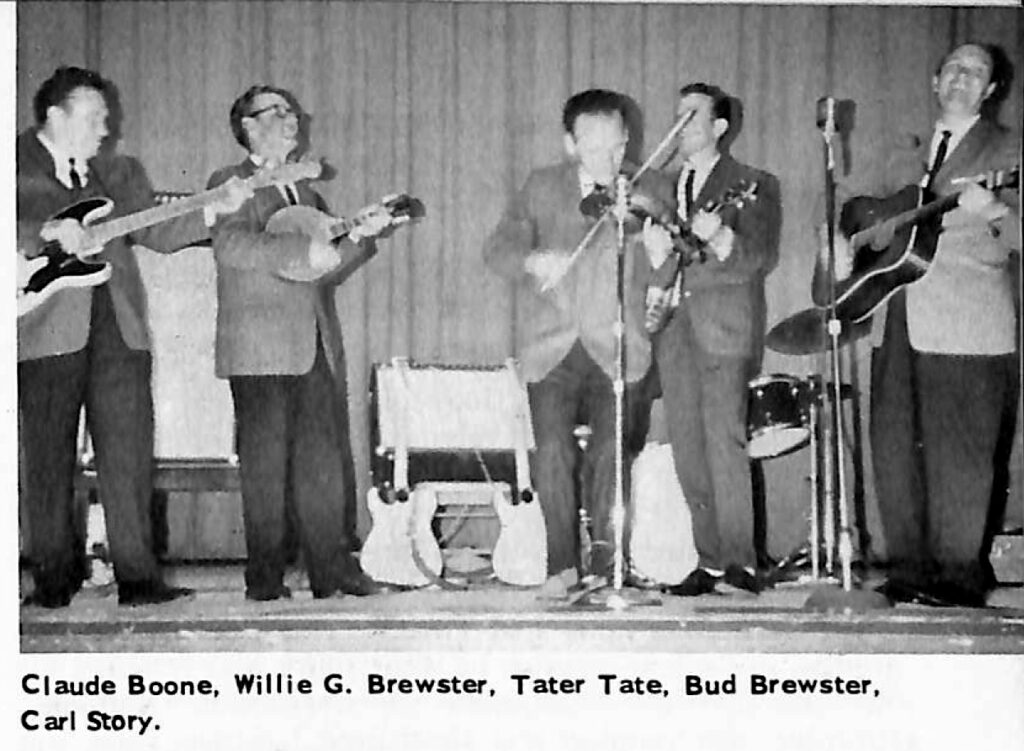

Before the end of the year, Tater returned to Knoxville where he worked on the Cas Walker show and simultaneously played personal appearances with Carl Story and the Rambling Mountaineers. This was during a time when Carl was recording extensively not only on Starday but on a number of other labels as well. At that time the Rambling Mountaineers also included Willie and Bud Brewster and Claude Boone, one of the best known Story ensembles. This group worked for the Knoxville supermarket owner on WBIR-TV in Knoxville five mornings per week.

In late summer of 1965, Tater returned to Gate City in somewhat of a quandary. An attractive job offer had been made by Jim and Jesse McReynolds, a duo he much admired both from a personal and professional viewpoint. Still, he was reluctant to get into a heavy road schedule similar to that which had plagued his health in earlier years. Knowing of Red Smiley’s success with the “Top O’the Morning Show” in Roanoke, he contacted him in hopes of landing a job with a group that did limited traveling. Although disappointed after his first conversation with Red, the next day he was invited to join the Bluegrass Cutups, replacing Ron Beverley on fiddle. He moved to Roanoke in October, 1965 and has called it home to this day. He now lives in suburban Hollins with his wife, Lois.

The three and one-half years Tater spent with Red were musically rewarding. The Bluegrass Cutups were a tightly knit group and one of the most respected in the business. In addition to their TV shows and appearances, the band cut four excellent albums, one on Rimrock and three on Rural Rhythm. With the help of the band Tater did two good fiddle albums, the first for Wayne Raney (Rimrock) and the second on Rural Rhythm. He also cut a couple of waltz albums on the latter label which he would almost as soon forget, partly because of some of the backing which was later dubbed in. The Cutups also helped a number of other Rural Rhythm artists on record sessions including Lee Moore, Hylo Brown, J.E. Mainer, Jim Eanes and Shot Jackson.

Bluegrass in the Roanoke area suffered a regrettable loss in late March, 1969 when WBDJ-TV cancelled the “Top O’the Morning” show. Red Smiley, in declining health, decided to retire in preference to taking a heavy road schedule. However, Tater along with John Palmer and Billy Edwards, decided to keep the band together. Herschel Sizemore, a skilled mandolin player and tenor singer from Alabama joined the group and for a while Jim Eanes played guitar and sang lead. Much of the time, however, the group consisted of only four men. Tater was forced to abandon his beloved fiddle for the guitar. Nonetheless, he still managed to do a few fiddle tunes on each show and was able to demonstrate his remarkable back-up work during those brief periods when Cliff Waldron, Udell McPeak and Tommy Connor played guitar. The addition of Wesley Golding on guitar with the group for the past two summers has enabled Tater to return to the fiddle on a permanent basis.

Since the spring of 1969, the Shenandoah Cutups (the name was a composite of Jim Eanes’ old group, the Shenandoah Valley Boys, with that of the Bluegrass Cutups) have performed on nearly all the major festivals and have become one of the best of the newer groups who have retained a more traditional format. They have perhaps been most appreciated by those who treasure the early Flatt and Scruggs sound. Six albums have been recorded by the group not all of which have been released at the time of this writing. At least two of them, “The Shenandoah Valley Quartet with Jim Eanes,” County 726, and “Bluegrass Autumn,” Revonah 904, must be considered among the best recordings of traditional bluegrass in the last decade.

The Cutups have undergone some recent personnel changes and have experimented with new material. The Tater Tate fiddle style, however, remains unchanged. The persisting expansion of bluegrass, primarily through the growth of festivals, almost guarantees that bluegrass fans will continue to be entertained by Tater Tate’s fiddling for some time to come.

Not all of Tater’s recording work has been limited to the fiddle. In addition to playing rhythm guitar on some of the Cutups’ recordings, he played a credible lead mandolin on some of the numbers on Red Smiley’s sacred album on Rimrock. This year at Bean Blossom, he played bass with Jim and Jesse on what is expected to be released on MCA as a live album at Bean Blossom. Although he doesn’t consider himself a banjo player, on rare occasions he can play clawhammer style while rendering an exacting imitation of Grandpa Jones.

Tater’s fiddling has also been heard on a number of recording sessions. Early in his career he fiddled on Carl Butler’s first Capitol session in Knoxville. He also cut with the Brewster Brothers on Acme. Over the years he assisted several other people — some relative unknowns — on their recordings. A few of these were country recordings such as those with Mabelle Seiger during his WWVA days with Hylo Brown. In the late 1960’s, he helped back a number of aforementioned Rural Rhythm artists. Tater himself cannot remember all the people he has assisted on recordings. Most recently, he accompanied banjoist, Buddy Rose, on an instrumental album and also got together with old friends, Charles and Danny Bailey, Jake Tullock and Larry Mathis for a session on Rounder. These were his first recordings with the Baileys since their Canary recording days in the early fifties (See Bluegrass Unlimited, February, 1971).

Among Tater’s proudest musical accomplishments has been his influence on Buddy Spicher, one of the best known studio musicians in Nashville. In his early days at WWVA, Tater helped the youthful Buddy in developing his fiddle style. In his second sojourn at the Jamboree several years later, the two were fortunate enough to play numerous shows together. Tater has always enjoyed twin fiddling whether it be with Buddy, Joe Stuart, Bobby Hicks, or as at recent festivals, with Chubby Wise.

Over the last twenty-five years, Clarence E. “Tater” Tate has almost constantly been a part of the bluegrass scene. Like Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley and others he has persevered through thick and thin! Fortunately for both him and bluegrass fans, he has been a key figure in some of the best bands ever assembled.