Home > Articles > The Archives > The New Coon Creek Girls

The New Coon Creek Girls

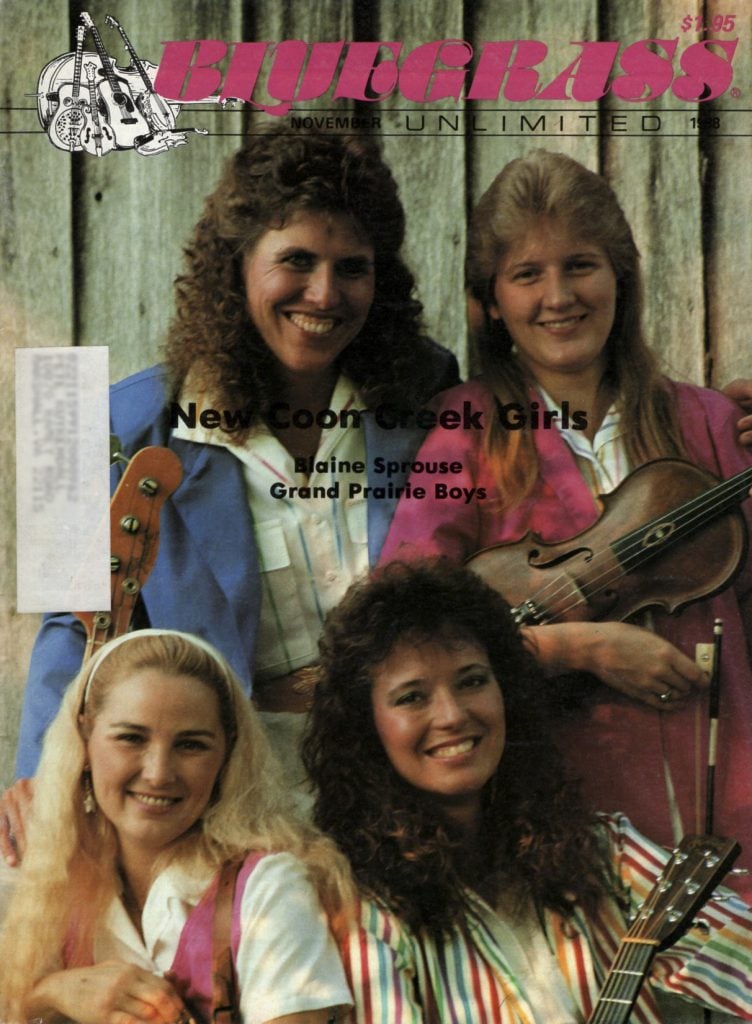

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1988, Volume 23, Number 5

“It’s sad but true that there are so few entertainers among some really superb musicians and singers in bluegrass music today. When people like Lester Flatt, Don Reno, Scotty Stoneman, Charlie Moore, ‘Cousin Jake’ Tullock and ‘Stringbean’ Akeman left us it was almost like the end of an era.” Nashville agent and artist management executive Lance LeRoy continues the thought: ‘‘On the festival stages these days—and even with some well-known artists—I see so much ‘dead time’ on stage: excessive tuning, ‘inside’ jokes, speaking in monotones, too much small talk and so forth. The music might be very good but if the ‘front work’ rambles and lacks focus, then people become distracted and tend to lose interest. You can imagine that it turns off people who are new to bluegrass and who we need to bring along with us.

‘‘There are some redeeming factors in the way the music is presented right now,” LeRoy says. “On the average, the standards for vocals and musicianship are much higher than they were even just ten years ago but so few of the artists of today have that special gift of also being entertainers! Some are able to overcome a rather dry presentation with sheer musical ability and personal charisma. The New Coon Creek Girls is a refreshing exception to what I see almost as a trend. It’s a shame that the group is forced by prejudice to start each show on an unlevel playing field. It’s a fact of life that in the minds of some people—many or possibly even most of them females themselves, by the way—in any audience, four girls up there on stage have to be exceptional in order to be judged merely ‘good.’ The band turns this into an advantage though by proving at the outset that they can ‘cut it’ with the best in the business—female or male—and this in itself draws attention. The girls’ stage presence is professional and their acumen for pacing an audience is very keen. Their smiles are warm and genuine and they look the people straight in the eye, holding their attention rather than appearing to talk over their heads. Above all, they never for one second lose sight of the fact that those folks came to see and hear the New Coon Creek Girls and paid to be entertained; it’s a show as contrasted to just pickin’ and singin’; there’s a vast difference. It’s ‘showmanship’ and they use it very discreetly but effectively. Of course there’s a fair number of fine showmen and entertainers working the festivals yet but not nearly enough. We lost a good one in the Johnson Mountain Boys. I’m afraid the ‘entertainer’ genre is on the ‘endangered species’ list in bluegrass music.”

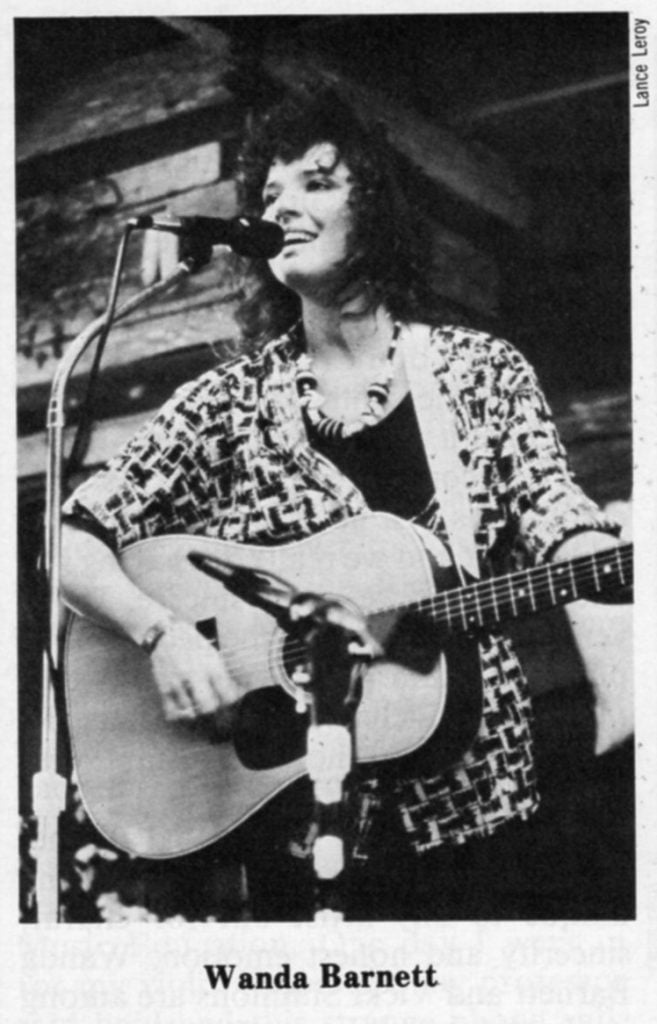

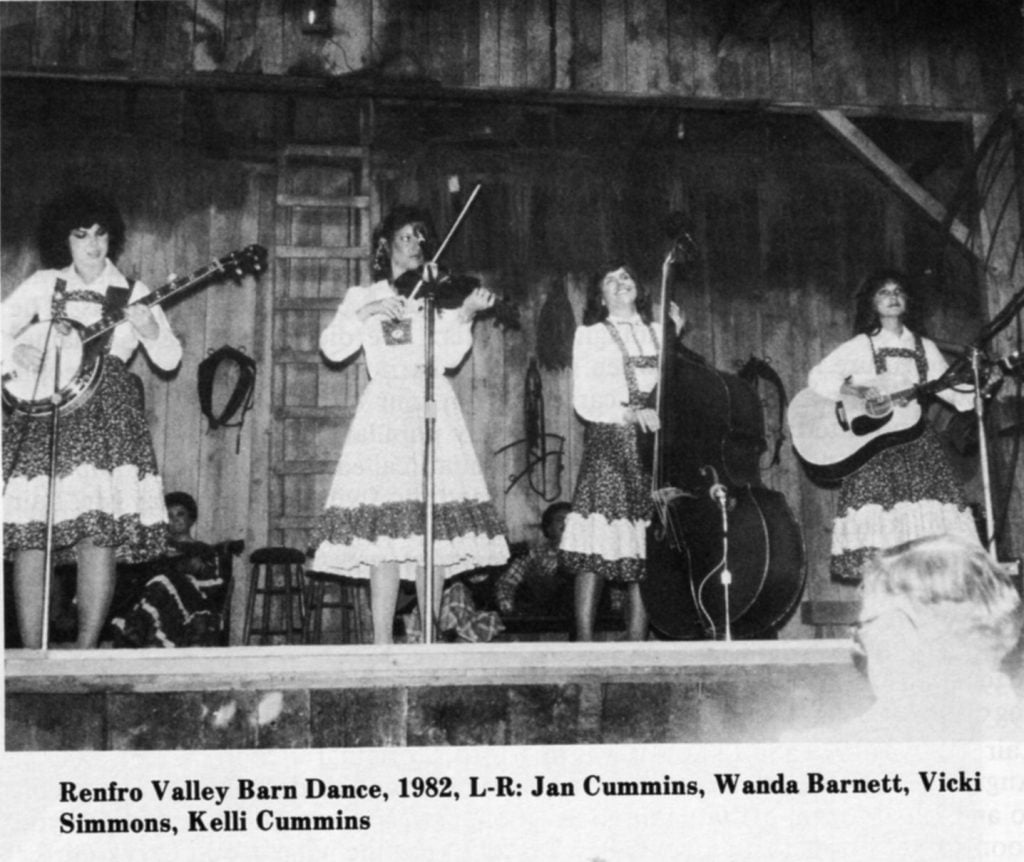

It’s logical that New Coon Creek Girls’ founding member Vicki Simmons and her partner Wanda Barnett would be well versed in the art of “selling” their music to an audience because both learned early-on from a master of showcasing and staging. Simmons could not have imagined what the future held for her when she launched what was to become a career in music and entertainment by stepping on a stage with no rehearsal. The stage was the huge-beamed, rustic, focal point of Kentucky’s legendary, five-decades-old Renfro Valley Barn Dance and, for a number of years, the CBS Radio Network’s “Sunday Morning Gathering,” headed from inception in 1939 until his death in November, 1985, by its colorful patriarch, John Lair. “It was 1979 and I know it was in August because we were cuttin’ tobacco and I had to run off late that afternoon to get down to Renfro Valley,” Simmons says, recalling her spontaneous decision to try out for an all girl band she had heard was being formed on the famous show located some fifteen miles from her hometown of Berea. “My mom said ‘Vicki, do you really think you’re ready for this?’ ‘I said ‘no’ and she said ‘LET’S GO ANYWAY!’ She was real supportive. So mom and I set out with the [upright] bass in the car, mom driving and me in the back seat to make room for the bass. When we got there, we met these two girls who didn’t even know we were coming. This was Jan and Kelli Cummins and they had picked up a fiddle player, Betty Lin from Frankfort, Indiana. The Cummins sisters and Betty Lin were playing every Saturday night but didn’t have a band name or anything. I went on stage with them without any rehearsal really and we just clicked. The addition of a bass just completed what was already there. When we got done I talked to John Lair and he asked me if I wanted this job. I asked what it paid and he said $25. That wasn’t much but I said ‘Yeah; sure I do! We played on into the 1980 season with the band as it was then and for months and months Mr. Lair had been introducing us as ‘The Girls.’ We didn’t even have a name! The barn dance got a lot of people from tour buses and there was then a very popular midday TV show in Cincinnati called the Bob Braun Show. It went into five states. One day Mr. Lair called us into his office and said ‘I want you to play the Bob Braun Show but we’ve got a problem, you don’t have a name. I’ve got two possibilities and one is the Sun Bonnet Girls.’ We all went—‘Boo, Hiss’ and he said ‘Well, I’ve talked to Lily May (Ledford, original Coon Creek Girls’ founder and leader) and she’s not a bit opposed and would be proud for you all to use the name Coon Creek Girls.’ So we added ‘New’ to it and we’ve tried ever since to be as good to the name as it’s been to us.”

The name “Coon Creek Girls” is in itself a powerful statement about one of the richest periods in the history of traditional country music in America, centered around the late 1930s and 1940s. In an era when women were beginning to play an important role in “hillbilly” music, the late Lily May Ledford was a pioneering free spirit. Unlike others of her generation and later who achieved great individual stardom, such as Patsy Montana, Rose Maddox and Molly O’Day, she chose instead to write a memorable chapter in the history book of country music under the name “Coon Creek Girls,” rather than under Lily May Ledford, which she could well have done. Honored by the National Endowment For The Arts as “a master American artist,” the Kentucky native’s splendid tenor voice and driving ‘clawhammer’ banjo work was first heard on radio as the leader and only permanent member of the Coon Creek Girls on October 9, 1937, from John Lair’s Barn Dance in Cincinnati. Lair moved his base of operations to Renfro Valley, Kentucky, two years later when he founded the Renfro Valley Barn Dance. The Coon Creek Girls went with him and remained as a member of the cast until 1957 when the group essentially disbanded except for a few rare reunion performances. The internationally-known troupe performed at the White House in Washington in 1938 for then-President and Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt with their guests, the king and queen of England. According to press reports at the time, “. . . the Coon Creek Girls were the hit of the evening with their songs, such as ‘How Many Biscuits Can You Eat?’ ”

Having had the legacy of the famous group name bestowed upon them by none other than Lily May Ledford herself, it’s hard to imagine anyone more sensitive to and appreciative of all that it represents than New Coon Creek Girls’ vocalist, bassist and clawhammer banjo player, Vicki Simmons.

“She was adorable, I mean the lady had such an air about her; graceful and captivating. To me, to an audience, to everybody.” The charismatic brunette continues: “Lily May was an ‘artist-in-residence’ at Berea College in Berea, where I live. She had been real sick and had stopped playing for a long time. I went up to her after one of her performances one day and told her I wanted to learn clawhammer banjo. She said ‘Oh honey you don’t want to learn this, you want to learn that three-finger stuff and I can’t teach you that.’ I said ‘No, I want to learn what you have to teach me.’ So we set it up. I started going to her as often as I could for lessons. She lived in a dorm on campus for a period of about four months. My uncle, Jay Begley, died in November, 1979, and my aunt gave me his banjo, a Gibson Mastertone, so I had it to work with. As we worked together, Lily May put the results on cassette tapes. Her voice had dropped to a lower register than it was years ago and she had arthritis very bad. It really hurt her to play. So that’s how I learned the clawhammer style of banjo and I’m real glad I did because she didn’t last long after that.”

The early days of the New Coon Creek Girls on the Renfro Valley Barn Dance was a learning experience. Having been officially named during 1980, the band had its first personnel change roughly a year later. ‘‘Betty Lin left at the end of the 1981 season—they closed down during the three winter months—so we started a search for another fiddle player,” relates Simmons. “I called over to Eastern Kentucky University in Richmond and came up with Wanda Barnett’s name and called her.” Reared in New Albany, Indiana, Barnett remembers the incident well. “After getting my bachelors degree from EKU, I taught music in the schools in southern Indiana, then went back to complete my graduate work for a masters degree in Music Education. One day I went in for my violin lesson and my professor said he’d had this strange phone call, something about a bluegrass band called ‘The Coon Creek Girls,’ he thought. But he went on to say that the caller said they’re a serious operation with some history behind them and not a fly-by-night thing. When I got Vicki on the phone she sounded country as cornbread but extremely, extremely friendly and made me feel really welcome so I went up with my violin and at the time I knew three fiddle tunes. After practicing a couple of hours with Jan, Kelli and Vicki, they—I guess—figured I’d do okay so we set out for the barn to get Mr. Lair’s approval. We auditioned for him and his daughter, Jennalee King and played the ‘Black Mountain Rag.’ Mr. Lair said ‘well, looks like you’ve got your girl,’ so it was settled. It was on a Sunday when I auditioned and I had to get an outfit together by the next Saturday night. At that time, we all wore gingham with big petticoats and a little bib.”

From the earliest days of the barn dance until the time of his death, John Lair had definite ideas about how he wanted his show run. He had, for instance, insisted that each of the Coon Creek Girls use stage names that incorporated the name of a flower. Thus, Esther Koehler became “Violet” and Evelyn Lange became “Daisy.” Lily May and her sister, Rosie Leford, completed the original group of 1937. Like its namesake, the New Coon Creek Girls soon attained headliner status and according to Simmons the atmosphere was congenial at all times. “We were like a big family. When I first joined, I’d work some on the ‘Sunday Morning Gathering.’ I’d just play or sing wherever I was needed. The barn was full every Saturday night with 600 people for each show so we were reaching 1200 people and had become the featured act. We got twenty minutes when almost everybody else only got like one or two songs so we began to build a following. There were very few nights during the year when the place wasn’t sold out. Tour buses came in from everywhere.”

The imposing, weathered, barnlike structure that houses the rough-hewn, starkly simple auditorium and stage of Renfro Valley’s most famous landmark made a lasting first impression on Barnett. “On my first night I couldn’t believe the place. There was this huge stage with four microphones and no [speaker] monitors. Mr. Lair didn’t believe in ’em. We sang all our trios into one microphone. When somebody would mention more microphones to him he’d ask ‘What do you need ’em for?’ The show was organized though and had a special air about it. We have many fond memories of it.” “When Wanda came in it was the spring of 1982,” adds Simmons. “Mr. Lair was no longer able to emcee the entire show but he still brought us on and took us off. People just idolized him.”

More so than several other nationally-known country music showplaces, the Renfro Valley Barn Dance has historically failed to keep many of its most popular artists and this has been attributed by some to its highly restrictive policies. The New Coon Creek Girls was no exception. Simmons remembers that Lair was physically unable even to go to his office when he sent word for the band members to come to his home. “We were about to start the 1983 season and he presented us with a contract that would have limited us musically so severely there was no way we could have signed it. It would have been foolish. Our leaving the show at that time was a business decision on our part and we left with no regrets.”

It was during this period that the band’s first LP, “How Many Biscuits Can You Eat” was recorded. Very traditional and now out of print, it contained many of the songs the group had featured on the barn dance.

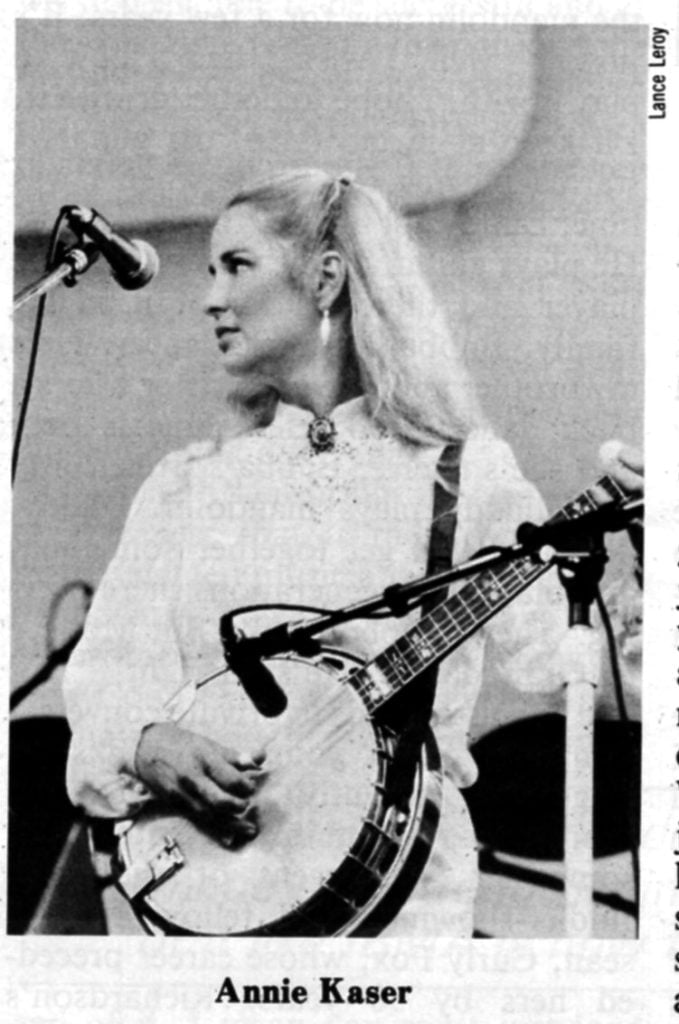

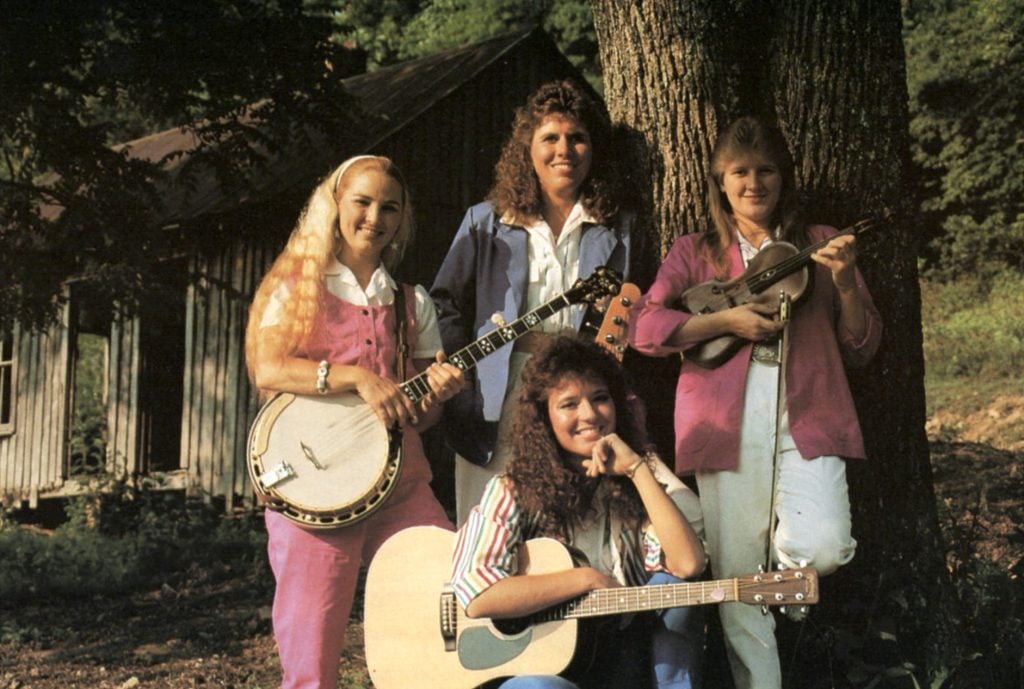

With the advent of Pam Gadd’s coming into the band playing banjo in June of 1983 and becoming even more pronounced when Pam Perry joined on mandolin in January, 1985, the choice of song material became remarkedly more toward original compositions and a mix of straight-ahead bluegrass and a country-influenced sound, rather than one dominated by old-time folk and novelty songs as in previous years. Barnett switched from fiddle to guitar with Simmons continuing on bass and this coalition produced the 1986 “Home Sweet Highway” LP, issued on the Rutabaga label and distributed by Old Homestead Records. Gadd was replaced on banjo by Annie Kaser January 1, 1987, and Perry was replaced by Deanie Richardson playing fiddle and mandolin on May 10th, 1988, bringing to the unit its current personnel.

As if predestined, present-day members of the New Coon Creek Girls embody many of the traits attributed to their predecessor namesake, such as an exuberant love of music and performing that withstands disappointments and transcends the rigors of travel. Lafayette, Indiana-native Annie Kaser personifies all the qualifications of a trouper. Playing an aggressive, forceful Scruggs style of banjo, her waist-length blonde tresses and radiant smile on stage—and off—are becoming increasingly better known pleasant familiarities to bluegrass fans everywhere. But there’s a side to her known primarily to co-workers and that is her willingness to do more than her share and especially the less glamorous work. “I like to drive on the trips. Actually I prefer to drive because it gives me something to do,” she says matter-of-factly. “That’s where I get my time to myself. I enjoy traveling, we enjoy each other’s company, meeting people where we play. I have never been happier playing music. This is ‘it’ to me. We treat it like a business. When we’re tired we’re mature enough to know when not to be around each other. I smile because I like to, not because I have to. I sometimes have to get warmed up on stage but then when I get to feeling the music I start smiling because I love it so much. I like traditional stuff. That’s about all I play. I’m hoping that bluegrass will continue to go back to the old sound like the Johnson Mountain Boys perpetuated. We try to keep the traditional sound but we play different songs. My all- time favorite banjo player is Earl Scruggs but the one who plays more like I hear in my head is J.D. Crowe. J.D. is a little bit different and plays like what I would like to play but Earl is a legend and he’ll always be number one.” Simmons adds, “Annie’s singing harmony parts more and more now. She does it so well, just like she plays harmony on the banjo.”

A musician of great talents, Kaser found it came naturally at an early age. “I started playing piano when I was four and took up electric bass when I was eleven, played in a rock ’n’ roll band, and between times taught myself finger-pickin’ guitar, which I taught lessons on all through high school. In college I taught myself classical guitar and only then did I take up the banjo. This was after I’d finished college and it was about 1976. I didn’t know a thing about bluegrass and I’d never heard a banjo player in my life until about six months after I’d started playing. I was teaching guitar in a music store and walked in one day and the store had one [a banjo] hanging up on the wall and I said ‘wrap it up, I want to take it home.’ I learned three rolls and I went home with it. There was a banjo player at the store. He taught me three songs and that was it. I just picked it up from there. For a while we had a band, the Carpenter Family, just to be able to play. After that we started Indiana’s first all-girl band. Patchwork, during 1977 and 1978. I just played with various bands after that. I’d heard the New Coon Creek Girls needed a new banjo player so we got together and we hit it off from the beginning.”

The fact that the New Coon Creek Girls’ stage presentation has almost consistently won encores from general audiences that included many fans not familiar with bluegrass music did not come about by chance. “That’s something that I credit to the Renfro Valley experience and the time we spent there,” explains Barnett. “From the very first day I went there it was grilled into me to have a good time, smile and be yourself.” Simmons adds, “It was so important to that show to not have a moment of dead time. I mean you didn’t have two seconds without something goin’ on. If you did it was the cane—you know, the hook—I mean literally! We like to keep humor in the show and we try to give the audience a little insight into the New Coon Creek Girls because if they know a little something about you then I feel they’re drawn closer to you. That’s why when I’m introducing everybody I don’t think I’ve ever done it exactly the same way twice. I don’t memorize it and that way I feel like it won’t become stereotyped.” Barnett emphasizes, “It never will! Because we ad-lib a lot and we really are having fun and whatever we say is sincere. We’re very careful to look at the people we’re playing to and not saying things that they aren’t included in. You must let your fans know how important they are to you.”

“Setting up” a song is a time-honored stage ploy and far from being unique to any artist but for charm, sincerity and honest emotion, Wanda Barnett and Vicki Simmons are among its best practitioners. The key word here is “honest,” because that is the only context in which they use it; when it has a legitimate application to a song they are about to sing. Barnett offers a remarkably ingenious explanation. “Every now and then there comes a song that has a great story and to just ‘throw it at ’em’ is a waste. If you can get the people to come along on the journey with you then you’ve got ’em; you’ve got their attention. It can make all the difference in the world.” Simmons elaborates: “The things you say can mean a lot. For instance, a song Wanda wrote entitled ‘Charlie.’ If she just went out and sang it, it wouldn’t have nearly the impact it does because she first says a few words about the song and the person she wrote it about and how much he meant to her. She’s had people tell her that because of what she said about the song tears came to their eyes. We try to say things that people can relate to in their own lives. Lily May was a master at this. She was not only a musician and singer but she was a great storyteller. She had a way of captivating you so that you were waiting for every word. There’s a lot of lessons to be learned from that. When I introduce ‘Pictures,’ the title song of our latest album, I tell the story behind the song and I’ve had people come up and tell me they used to do the very same things when they were a kid in Mississippi, or wherever. When somebody tells you something like that about something you’ve written it’s about the highest compliment I could get. It relates to most anybody. It’s not like you have to have been from eastern Kentucky to have done those things.”

“You have to relate to your audience,” counsels Barnett. “A band should always remember to not play ‘over the heads’ of its audience. Hot licks are fine but if they’re not what the people want to hear then you need to be playing something that’s more appealing to them. It used to worry me a lot and I tried to impress other musicians but when we got to playing the major festivals with the ‘big guys’ I realized that they weren’t concerned with other musicians but were trying to sell themselves to the audience and that solved a lot of problems for me.” Simmons adds, “We all want the respect of our peers. But when you come to grips with it in your own mind and just say ‘I’m playing what these people want to hear,’ then it opens up a whole new world because you’re free from the worry of whether or not you’re impressing anybody.”

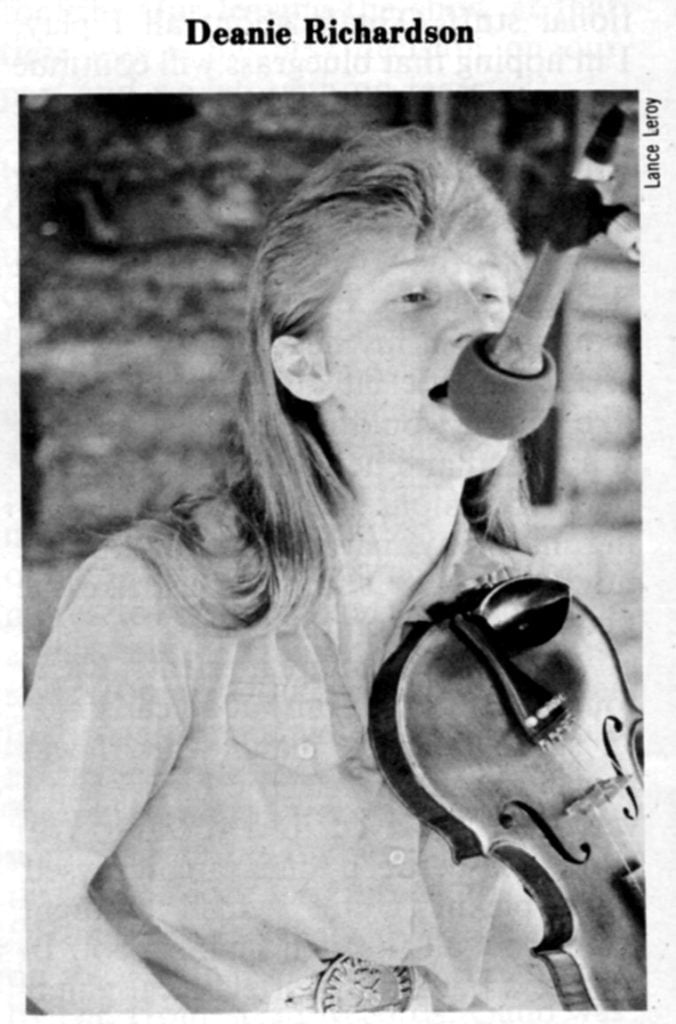

“We’re aware of the need to keep variety in the show and we have a lot of subjects and material to draw from,” says Simmons. The addition of sixteen- year-old Deanie Richardson to the group has added still another dimensition as well as a tremendous amount of musicianship and vocal talent. Having accomplished the unprecedented feat of placing fourth—at age thirteen—in Opryland’s invitational, ultra-prestigious Grand Masters fiddle contest in Nashville and seventh and fifth in the two succeeding years, the Kingston Springs, Tennessee-native is the 1987 State Champion Fiddler for the state of Kentucky and holds the Tennessee state championship for 1988. Like the Grand Masters, both state championships were in competition with top fiddlers from all over the country, vying for the cash awards that go with the honors. “I loved contests; did ’em for seven years but I got tired of it and I want to move on to something else,” Deanie says. “But I love playing with the band. I love just being up there and doin’ it and not having to do it for competition. I don’t mind traveling at all. As long as I’m playing I don’t care.” Coming from a musically-talented family, Richardson’s inherent creativity and proficiency is equalled only by an advanced case of modesty. “I’ve been tryin’ to play the mandolin now for a few years. It’s just . . . well, I wish I had a bow to play it with. I hope to do better with it. I’ll keep at it and (also) the guitar. I started playing the fiddle when I was nine; Daddy got me one for Christmas. He plays guitar and he wanted a fiddle player and there’s a lot of it in the family. Bubba’s a buck dancer. He’s my brother and I’ve got a sister who’s a buck dancer, too. Her name is Beth and she’s twelve; Bubba’s fifteen. My granddaddy plays mandolin. Daddy, he and I will get together sometimes and play; three generations there playing. There’s nobody like Bill Monroe to Granddaddy. He’s all right!” Not one to waste words in private conversation, the gifted youngster walks on stage and instantly becomes an irrepressible, uninhibited entertainer somewhat reminiscent of the great fiddler-showman and fellow Tennessean, Curly Fox, whose career preceded hers by 50 years. Richardson’s strong, raw and bluesy vocal style, combined with subtle body english generated by utter enjoyment of the music, is dynamite with audiences. With Vicki, Wanda and Annie contributing heavily to the fun, the fuse is lit at all times. In typical “Deanieism,” Richardson succinctly sums up the fact of her playing music for a living with an infectious smile. “I guess it was just meant to be.”

Comments made by Wanda Barnett epitomize the general feelings of the quartet’s members concerning the manner in which their music is presented and its relationship to bluegrass music as an industry. “Bluegrass badly needs a more professional image and strengthening of the business end of it like IBMA (International Bluegrass Music Association) is now trying to do,” she says emphatically. “We as artists can do a lot to improve the image of bluegrass in the eyes of fans and the general public. You should be professional in your stage show, professional in your music, professional in your dress and these are things that will help keep bluegrass music alive. When people pay their money to come through the gate they expect to see and hear something that’s better than what they can do or that’s enjoyable to them. We’ve experimented with our stage dress and we feel it’s better to dress in good taste but to not wear costumes. We do try to coordinate colors so they don’t clash on stage but we dress to our individual tastes; it works better for us.”

“As to what we sing and play on stage, we’ve got a lot of subjects and styles to draw from,” offers Simmons. “For instance a traditional Carter Family tune; a banjo tune; a clawhammer banjo or a fiddle tune; and an a cappella vocal or a fiddle and banjo instrumental. The ‘Hank Williams Medley’ and the ‘Patsy Cline Medley’ also go over well.” Barnett adds, “The a cappella song on our new album has been real effective for us. We’ve learned to ‘stack’ our harmony so that we have a consistent and identifiable sound regardless of who’s singing lead.” Simmons explains further: “Wanda can handle the top two parts and I can handle the bottom two parts.”

The late Lester Flatt, as well as others, made reference to the clawhammer style of banjo as drop thumb style. As defined by Simmons, the latter term seems quite appropriate for the delightfully rhythmic and seldom-heard old-time form of music: “Nobody much plays clawhammer these days and I really think it’s because there’s not many people to teach it. A lot of people don’t even know what clawhammer is. It’s not that hard to do but it’s totally different from the three-finger style. It involves the whole hand and wrist. You have to rock your whole wrist and use your thumb; drop it down on the strings. That thumb is just droning on that fifth string all the time. The sound is very rhythmical. It has a beat like a horse galloping. The melody note can be played with either the first or second finger; I use my first one. Then you drop your thumb on the fifth string. It’s all a downstroke.”

Of vital importance to everyone who enjoys bluegrass music is its future. This is so especially to those who earn their entire livelihood from playing music. It is always interesting to elicit the comments of the really perceptive artists who have observed the effects of other forms of music on bluegrass and, in turn, how bluegrass has affected other styles, most notably its first cousin, traditional country music. “People, I think, are getting tired of overproduced country music and I see a trend back toward bluegrass and acoustic instruments; I see it all the time,” Simmons states. “A lot of country musicians with bluegrass backgrounds are incorporating that into their country music, which gives a bluegrass ‘flavor’ to it. I see a need for people to accept some expansion on the basic bluegrass style. But on the other hand, there’ll always be traditional bluegrass as we know it today. The key to being successful with it in my opinion is the way the Johnson Mountain Boys, for example, did it. They were traditional but they wrote their own stuff and it wasn’t like they were imitators.” Barnett explains further, “Some of the festivals aren’t drawing younger people. I think in a lot of cases it’s because the promoter hires the bands who play just what he or she likes and nothing else. I’m proud that we’ve been able to be successful and at the same time preserve the music of the original Coon Creek Girls while doing our own songs by four girls with very different backgrounds. I think the key to keeping bluegrass alive and healthy is the acceptance of the different styles. People like Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs didn’t get where they are by following exactly what had been done before them. They experimented and did something different.”

Barnett then brings up a phase of the business that is the downfall of many talented musicians. “In addition to having grown as musicians and entertainers, a vital part of it is how the New Coon Creek Girls has grown as a business. There is a definite business end of it. I mean you can’t just love your music and go out there and play it. To survive you have to look after all phases of your show. We went from playing one night a week on the barn dance, no merchandise, no mode of transportation, to where we now travel extensively, have a motorhome to be responsible for, albums, tapes, T-shirts, recording commitments, etc. and these are the challenges that have come along and they have to be reckoned with.” Vicki Simmons interjects, “January 1, 1987, was a turning point for the New Coon Creek Girls in a couple of respects. Annie joined us on five-string banjo, giving the group the traditional sound we needed. At the same time, we also joined the roster of the Lancer Agency, based in the Nashville suburb of Hendersonville, Tennessee. Lance LeRoy owns the agency and for a number of years he was Lester Flatt’s manager and agent. Before January, 1987, I was doing a lot of the booking of appearances and with all the other things we had to do, Wanda and I didn’t have any free time. Lance is respected and has a thorough understanding of the industry. He believes in our group and our music and he’s also our manager. His guidance, advice and friendship over the past two years has been invaluable to us. Among some good things that’s happened for us recently are a guest appearance on the Grand Ole Opry and a visit with Earl and Louise Scruggs in their home. It was an opportunity I never thought I’d have. I actually got to shake hands with Earl and talk with him and tell him in person how much pleasure his music has given us. It was a very special evening for us.” Wanda adds, “Earl and Louise are very gracious people and it was a thrill just to sit and listen to Earl talk and to hear a few ‘tales’ of times that he and the Foggy Mountain Boys shared. I no longer just admire what Earl did musically but I now also have additional respect for him as a person. He’s a real gentleman.”

Between performances at an annual celebration in Tennessee this past July, the girls visited the cabin that is the birthplace and boyhood home of Lester Flatt. Two of the photographs for this story, including the cover photo, were taken in front of the quaint, four-room structure that dates to the beginning of this century or before. The present owner of the property, Reverend Malcolm Hill, says. “I’m as sure as I can be that Lester wrote the song ‘Little Cabin Home On The Hill’ about this place.” Officially credited by Peer-Southern Publishing Company as being co-written by Flatt and Bill Monroe, the song was honored by the late Elvis Presley in his “Elvis Country” album for RCA Records. Standing in the door of the cabin, there can be little doubt that Flatt had this place in mind when he wrote: “. . . Now when you have come, to the end of the way, and find there’s no more happiness for you; just let your thoughts turn back, once more if you will, to our little cabin home on the hill …” “Standing there, overlooking that beautiful, peaceful valley,” Simmons remembers, “Lester became a real person and not just a voice on a piece of black vinyl. When I was learning to play from my Uncle Jay, the sound of Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs was consuming and their music became all I wanted to listen to and learn how to play.” Barnett adds, “The man and his music became doubly real to me. It’s easy for me to see now why he sang about the simple pleasures of country life and growing up and why his songs to this day touch and relate to so many people. Earl and Lester’s music will live always because everybody has roots.

“Of all the audiences we’ve played to, there’s none like those at the Grand Ole Opry for warmth and energy,” says Barnett enthusiastically. “When we did a guest spot on the Opry last July second, we had to rush to the Grand Ole Opry House from the festival stage over in Opryland Park, so we didn’t have time to get nervous. Jack Greene gave us a gracious introduction and put us at ease. When we finished the one song we were scheduled to do, it was a very intense moment and one that I’ll never forget. You could sense a lot of love from those folks and you could tell that they liked us, not just the particular song we played. That kind of thing is magical and there’s no putting your finger on it. But as exciting as it was, I felt very much at home there.” Simmons picks up the story ecstatically: “We just were not prepared for the spontaneous, overwhelming ovation we received. To get called back for an additional song was an indescribable thrill and for one of the few times in my life I was speechless! It ran through my mind though that here I was—Vicki Hymer Simmons; winner of the 1972 FHA talent show in Berea, Kentucky—fulfilling a lifelong dream to perform on the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville.”

“We’re extremely proud of our association with Pat Martin and Turquoise Records during 1988,” offers Simmons. “Pat has a great background in production and marketing and we like the attention she gives to detail and quality. The label is quickly becoming known for recording a variety of artists and their different styles of music. Our latest album, ‘Pictures,’ is on Turquoise and was shipped in August. The response to it so far has been good and we’re immensely pleased with the product and especially the jacket design that was done by Jan Bennett.”

Barnett points to a new recording project that is already well under way, the release schedule of which is dependent on buyer reaction to ‘Pictures’: “Most things are more successful when they have direction and the recording project we’re working on now certainly has that,” she says. “It’s planned as a concept album, concentrating on straight bluegrass. Thanks to Lance’s record collection, we’ve had access to a lot of great music and that’s been the hardest part, just choosing. After hours and hours of intense listening to old records and tape recordings, I have a renewed respect for Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs, Osborne Brothers, Louvin Brothers, Jimmy Martin, Mac Wiseman and some others. What they did, how they did it and when they did it is to be admired. You just don’t realize all that ’til you start trying to reproduce some of it! But it’s been great fun and I’m looking forward more to this album than any we’ve ever done.”

Words spoken with conviction by Wanda Barnett near the conclusion of a lengthy interview go a long way toward defining the devotion and dedication she and her colleagues have to the music that is the foundation on which their own music is built. “I think it should be required, before anyone buys his first banjo or guitar, before anyone ever hits the first chord or sings the first song and claims to be a bluegrass musician or a bluegrass band, to study Earl and Lester and Bill. It would take a book to describe all they initiated musically.”

Regarded by some insiders as currently the fastest-emerging group to enter the upper echelon of acts with a national reputation, the New Coon Creek Girls’ members quickly dismiss with typical tact and decorum any comparisons to other all-girl units, preferring instead to live up to the manner in which the talented foursome is most often thought of by its peers and fans alike: as one of the most entertaining and musically professional bluegrass groups in America, without qualification.

The four charming, vivacious, warm and beautiful people who comprise the New Coon Creek Girls—Vicki Simmons, Wanda Barnett, Annie Kaser and Deanie Richardson—and, barring some cruel stroke of fate, will continue to be—a credit to and a vital part of mainstream bluegrass music.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

This article is so relevant to the state of Bluegrass music today. There is opportunity here, and I hope bands read this and get inspired.