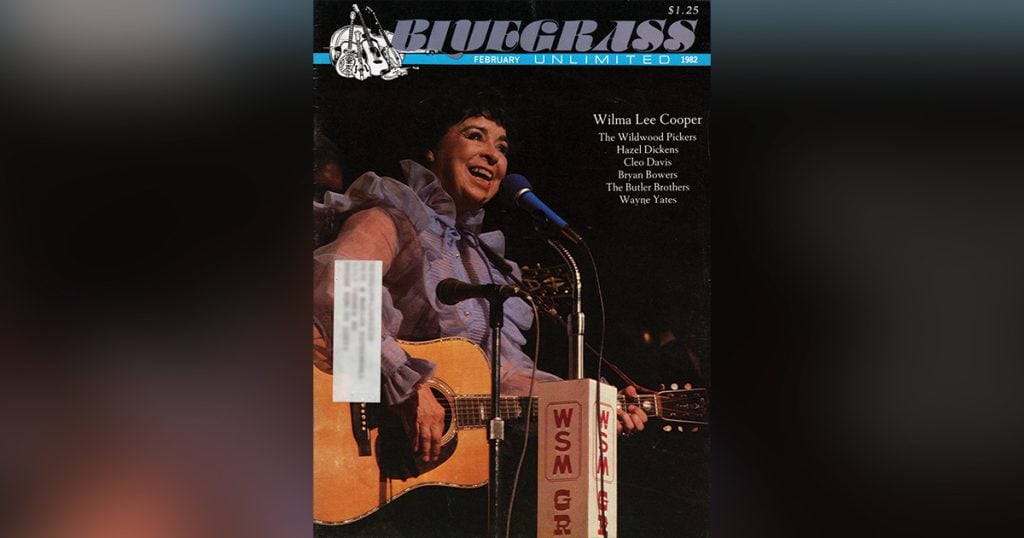

Home > Articles > The Archives > Wilma Lee Cooper: America’s Most Authentic Mountain Singer

Wilma Lee Cooper: America’s Most Authentic Mountain Singer

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1982, Volume 16, Number 8

For years the role of women in country music has been a topic of discussion by critics and historians of that field of popular entertainment. From one extreme come statements such as that of author Dorothy Horstman who has said that “Country music until the very recent past was an almost completely male-dominated art form. As men traditionally ruled southern rural society, so they monopolized its popular music, relegating women to the status of minor performers or worshipful fans.” On the other hand, we find writers who share the opinion of Robert Coltman who has stated that the contributions of women to the development of country music “were remarkable in many ways, exerting an effect out of proportion to their numbers. It can be argued,” he continues, “that women’s presence helped change the nature of country music by 1940 in directions that, if the field had been left to men, might never have been taken.”

With respect to bluegrass music, the statement made in 1975 by Steven D. Price in his book, “Old As the Hills,” appears to have gone unchallenged. He said that “Bluegrass is almost an exclusively male province, most likely because the early bands…had no women members, and people just assumed that Bluegrass…was a fraternity.” Price goes on to say that “musicians have been associated with loose living, so playing in a band was considered too damaging to a woman’s reputation.”

If bluegrass and country music have indeed been dominated by males, the domination has not been complete, and no performer has been more successful in overcoming the sex barrier (whether real or imagined) than Wilma Lee Cooper who has made her mark in both musical categories.

Born in Valley Head, a hamlet located at the edge of the Monongahela National Forest in the rugged mountain region of eastern West Virginia, Wilma Lee Leary, at the age of five, embarked on a musical career that has been conspicuous by its adherence to the traditions from which it sprang. “I sing just like I did back when I was growing up there in those mountains of West Virginia,” vowed Wilma Lee during a recent interview. “I’ve never changed. I can’t change. I couldn’t sing any other way.”

The daughter of musically talented parents, Wilma Lee, along with her two sisters, Jerry and Peggy, cut their musical teeth on gospel harmonies. “I got my start in gospel music with my family,” she explains when introducing the sacred numbers that audiences have come to expect at her performances. “Mother and Daddy would sing nothing but gospel—the old four-part harmony, shaped note style—and my daddy had a fine bass voice.” Among the many religious songs composing the Leary family repertoire were church hymns like “Amazing Grace,” and gospel standards such as “Farther Along,” “He Will Set Your Fields on Fire,” and “Jesus, Hold My Hand.”

After several years of performing to local audiences in churches and school auditoriums, the Leary Family, in 1938, achieved national recognition when they were selected, through regional and state talent contest eliminations, to represent the state of West Virginia at the National Folk Festival in Washington, D.C. As a result of this exposure, Mr. Leary obtained a job for the family at radio station WSVA in Harrisonburg, Virginia, where, according to Wilma Lee, they had “the most popular show in that whole area. People loved a family that sang the gospel music,” she says, “and we had the listeners!” In 1941 the Learys increased their following when they moved to WWVA (then a 5,000 watt station) in Wheeling, West Virginia.

While Wilma Lee was growing up and learning the rudiments of show business as vocalist and guitar accompanist with her family, some forty miles, as the crow flies, northeast of Valley Head, at Harmon, West Virginia, another young musician was listening to the Grand Ole Opry every Saturday night and aspiring to play the fiddle like his idol, Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith. Dale Troy “Stoney” Cooper took his first step into professional musicianship at an early age when he accepted a job as fiddle player with a group known as the Green Valley Boys headed by a chap named Rusty Hiser. It was while Stoney was performing with this band on radio station WMMN in Fairmont, West Virginia, that the Leary Family heard him and decided he was the one they needed to replace Mrs. Leary’s brother who had given up his job as summertime fiddle player with the family to return to his regular vocation as a school teacher.

Stoney took the job and, although he didn’t know it at the time, his association with the Leary family would be permanent. Stoney and Wilma Lee were married in 1941, and when their daughter, Carol Lee (now leader of Nashville’s Carol Lee Singers), was born, the couple became temporary show business dropouts while Stoney drove a soft drink delivery truck in an effort to provide a better living for his family.

After six months Wilma Lee and Stoney, who had grown tired of their no doubt relatively prosaic existence as housewife and truck driver, resumed the country music career that they never again would abandon. This time, the Coopers struck out on their own, and during the next several years the course they pursued provided a classic example of the routine followed by country music acts of the 1930s and 1940s. They toured the country, performing on some radio station and making personal appearances in an area until the territory had been “worked out” and then moving on to another locality. As Wilma Lee frequently points out when discussing her career, “We made our name in the days of the radio;” in the days before the success of an artist was measured almost solely in terms of the number of hit records sold.

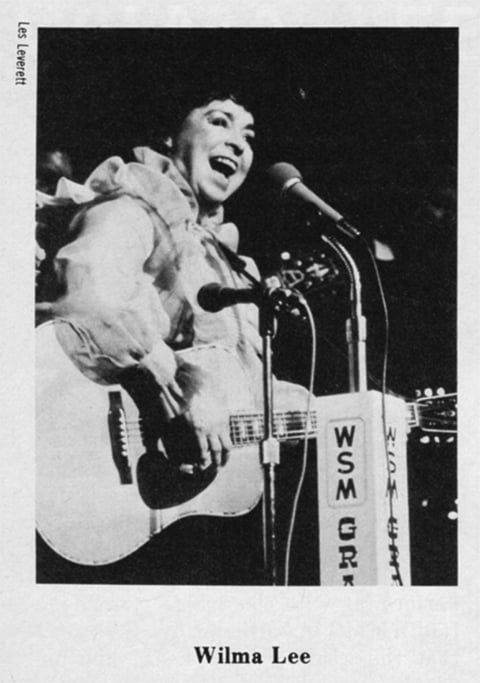

The first stop on the Coopers’ musical odyssey was radio station KMMJ, Grand Island, Nebraska, followed by stints of varying durations at WIBC, Indianapolis; WJJD, Chicago; WMMN, Fairmont, West Virginia; KLCN, Blytheville, Arkansas; WWNC, Asheville, North Carolina; WRVA, Richmond, Virginia; WWVA, Wheeling, West Virginia; and finally WSM and the Grand Ole Opry which they joined on January 12, 1957. Stoney, along with Wilma Lee, was a member of the Grand Ole Opry cast until his death on March 22, 1977; and Wilma Lee has since continued to be one of the show’s most faithful performers and almost solitary reminder of the kind of music on which the Opry was founded. While at Grand Island, Nebraska, and Indianapolis, the Coopers were joined by the rest of the Learys, so that for a while the entire family was again performing together. Later, when Wilma Lee and Stoney would have their own band they would call it the Clinch Mountain Clan in honor of a range of mountains near their ancestral home.

During the ten years (1947-1957) that Wilma Lee and Stoney were serving their second hitch at Wheeling’s WWVA, they experienced the greatest exposure of their career up to that time. By then the station, which had increased its power to 50,000 watts, blanketed the northeast and much of Canada. Other country music stars and future bluegrass notables who, over the years, shared billing with the Coopers at WWVA, included Pete Cassell, Hawkshaw Hawkins, Billy Grammer, George Morgan, Toby Stroud with Don Reno and Red Smiley, and Big Slim, the Lone Cowboy. In 1947, the manufacturers of Carter’s Little Liver Pills hired Wilma Lee and Stoney to do a series of transcribed shows that were aired over twenty different 50,000 watt radio stations over the country. Recording sessions with Rich-R-Tone (1947), Columbia (each year from 1949 to 1953), and Hickory (1955 and 1956) added to their stature, and by the time they joined the Grand Ole Opry they were a well-established country act with a large following.

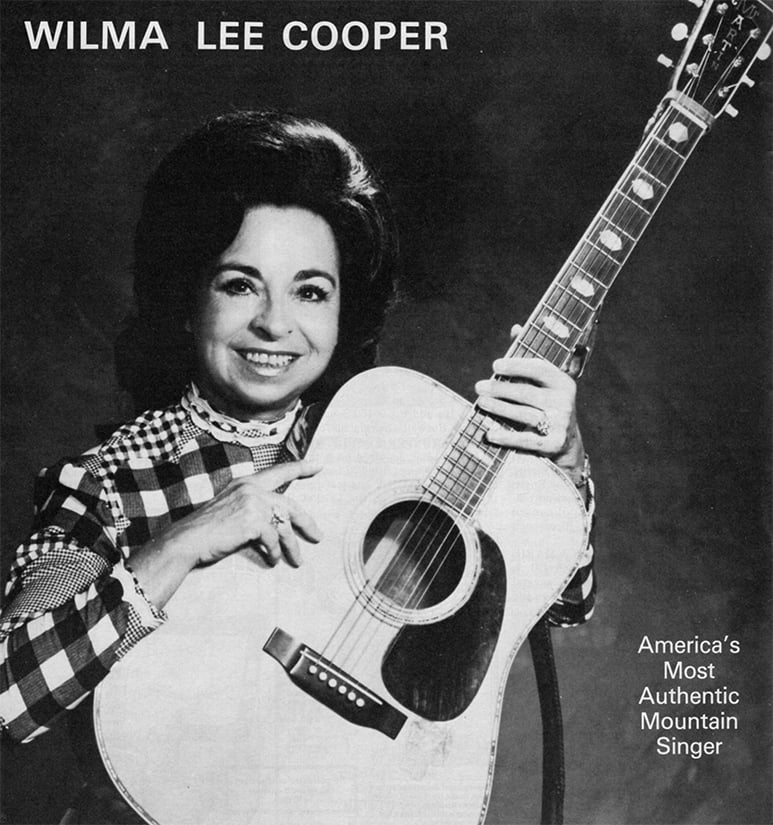

The question of whether or not Wilma Lee’s musical style should be classified as bluegrass has been frequently debated. She, herself, says, “I would say my style is just the old mountain style of singing. I am traditional country. I’m a country singer with the mountain whang to it.” In 1950 the Harvard University Library of Music personnel, during a field trip south to collect the Coopers’ music, christened them the most authentic mountain singing group in America, and Wilma Lee believes that the description is still applicable to her present style. “Who else,” she asks, “is doing my kind of music? I don’t know of anyone [who is doing it] professionally.

“When we came into Nashville, they started classifying music—giving it a name of some kind,” she continues. “And they would say we were bluegrass, but Stoney would say, ‘We’re not exactly bluegrass. We’re just country.’ And they would say, ‘Yes, you’re bluegrass.’ Then you don’t know what to call yourself.”

According to Wilma Lee, “People put you where they want you,” and no less authority than Bill Monroe has told her that she fits in the bluegrass category. Wilma Lee also emphasizes that fans have a say in the matter, and to her their views are important. “I was doing that Gail Davies song, ‘Bucket to the South’,” she relates. “I thought it was just a good old country sound, but some of my fans called, and wrote me, and said they thought that song just didn’t fit me. They said it was just a little too rocky and rolly for me. So I quit doing it.”

Several factors have contributed to Wilma Lee’s acceptance by bluegrass audiences. First of all, there’s her voice which has the range, timbre, and punch usually associated with the bluegrass sound. The lively, rollicking nature of her stage performances, coupled with an unmistakable aura of sincerity that can be described best as old-time country soul, appeals to the bluegrass devotee. In addition, the instrumentation of the Cooper band, with its fiddle, Dobro, and Scruggs style banjo, has long been identifiable as that of a bluegrass band. Finally, there’s the matter of repertoire. Many of the songs Wilma Lee has recorded, as well as those she sings on stage, have been drawn from bluegrass sources or have become bluegrass standards, due, in part perhaps, to her own efforts. On their very first trip into a recording studio, the Coopers carried with them Bill Monroe’s “Wicked Path of Sin.” (One of the earliest recordings, circa 1947, of the bluegrass style that was not by Bill Monroe.) Wilma Lee’s subsequent recordings have included such now bluegrass favorites as Cousin Emmy’s “Ruby” (recorded under the title, “Stoney, Are You Mad at Your Gal”), Don Reno’s “I’m Using My Bible for a Road Map,” “Shackles and Chains,” “He Will Set Your Fields on Fire,” “Sunny Side of the Mountain,” and Bill Monroe’s “Uncle Pen.”

In his essay of the Coopers, writer Robert Cogswell states that they have been associated with the Roy Acuff “school” of music and that when they moved to WJJD in Chicago, Wilma Lee was welcomed there as “the she-Roy Acuff.” “Well, we both have strong voices, and we both sing loud,” Wilma Lee comments by way of explanation. “He’s like a mountain singer. He grew up there in those mountains of east Tennessee. So I guess our [similar] backgrounds have a lot to do with it. I was one of Hank Williams’ favorite women singers and Roy Acuff was his favorite male singer. So, you see, there’s the two styles again. Hank said that what he liked about me was that I sang out. I opened my mouth and sang out, he said.”

The careers of Wilma Lee Cooper and Roy Acuff have been linked in other ways, too. They first met in 1938 in Harrisonburg, Virginia. “He came there to work a circuit of theaters in the surrounding towns,” Wilma Lee recalls, “and he brought his whole group up to station WSVA to be on the Leary Family program and advertise his show dates.” In Dorothy Horstman’s book, “Sing Your Heart Out, Country Boy,” Acuff relates a happy sequel to his early contact with the Learys. While performing in Virginia he heard Wilma Lee sing an old prison ballad called “The Hills of Roane County.” He liked the tune and later, when he wrote “The Precious Jewel,” his third most popular song (after “Wabash Cannon Ball” and “Great Speckled Bird”), he subconsciously set the words to the melody of the song he had heard Wilma Lee sing several years before. It was not until afterwards that he realized the two songs had the same tune. Fortunately, “The Hills of Roane County” was in the public domain, and Acuff was not liable for copyright infringement.

There is considerable overlap between Wilma Lee’s recorded output and that of Roy Acuff. At their first recording session, at least five of the Coopers’ sixteen cuts were songs recorded also by Acuff: “Little Rosewood Casket,” “What Will I Do,” “Two Little Orphans,” “This World Can’t Stand Long,” and “What Good Will It Do?” There may have been more, but five unissued masters from the session have been lost, and no one connected with the event seems to remember their titles* Other songs recorded by both Wilma Lee and Acuff include “Willie Roy, the Crippled Boy,” “The Legend of the Dogwood Tree,” “Each Season Changes You,” “I Want to Be Loved,” “Wreck on the Highway,” “Great Speckled Bird,” and “When I Lay My Burden Down.” In 1972 Wilma Lee and Stoney did an album on the Skylite Country label entitled, “A Tribute to Roy Acuff: The Great Speckled Bird.”

The Coopers’ long-time use of the Dobro, too, has been a constant reminder of the similarities of their music to that of Roy Acuff. Stoney was the band’s first Dobro player, introducing the instrument into the band in the early forties. Other Dobro players who have served time with the Clinch Mountain Clan include Josh Graves, who was with the band for six years, and Bill Carver, a performer with the group both before and after Graves’ stint. Another Dobroist, Ralph Jones, was with the band for a short time.

Wilma Lee is noted for the clear diction of her vocal delivery. She explains that there are two reasons why she has always made it a point to pronounce her words plainly when singing. “When I was a kid growing up, you got your songs off the radio. While someone was singing a song you’d try to write it down. Many times someone would be singing, and you couldn’t tell what they were saying. Just because of that I have always made it a point, when I sing, to try to speak my words as plainly as I can, so folks will know what I am saying.” She notes further that she sings a lot of story songs, and if listeners don’t understand the words to that type of song they miss the story, and as a consequence, they won’t like the song.

Another characteristic of Wilma Lee’s performances is the proficiency of her microphone technique, an accomplishment that enables her to put her songs across effectively even when forced to perform with inferior sound systems. “Back in the old days of show business,” she explains, “we only had one microphone, and you learned to use that mike in and out. You worked it. As you came to a low note you leaned in a little closer so the note would be stronger, and when you came to a note you were hitting hard, you would lean back a little. The whole band had to learn to work the microphone in and out. When one person finished he would move back and the next person would move in to the mike to pick his part.”

An early ambition of the Coopers was to have their music recorded commercially. Once achieved, however, they found that the life of a recording artist is not without its frustrations. Artists and record producers, for example, don’t always agree on what songs should be recorded. “We were due for a recording session,” Wilma Lee remarks by way of illustration, “and we heard this tune called ‘I Dreamed of a Hillbilly Heaven.’ It had just come out on a little label. This was before Tex Ritter or any of them had it. So Stoney called [their record producer at the time] and said, ‘I sure would like to do this song,’ and the producer’s reply was, ‘Oh, that song’s not going to do anything’.” “Hillbilly Heaven” became one of Tex Ritter’s biggest hits.

The Coopers were faced sometimes with the difficulty of working with a producer who was not what one would call an old-time music enthusiast. Recalling one recording session that took place under such circumstances, Wilma Lee says, “We barely got four sides recorded. They just didn’t understand our kind of music.”

There have been producers, too, Wilma Lee notes, who “wanted me to record material that I don’t sing on stage —would never sing. It really doesn’t help you much [to record songs] if you don’t sing them [on personal appearances],” she laments.

In addition to Rich-R-Tone, Columbia, Skylite Country, and Hickory, the Coopers’ music can be heard also on singles and/or albums released by Decca, Power Pak/Gusto, Rounder, DJM (a compilation from their work with Hickory between 1955 and 1964), County (a reissue album released in collaboration with Columbia), and Starday. From the Coopers’ recordings have come four top-ten country hits, “Come Walk With Me,” “There’s a Big Wheel,” “Big Midnight Special” (all three recorded for Hickory in 1959), and “Wreck on the Highway” (1961). Other songs that have been of particular help to Wilma Lee in retaining her popularity over the years include the Grady and Hazel Cole standard, “Tramp on the Street”; Juanita Moore’s “The Legend of the Dogwood Tree”; and “Walking My Lord Up Calvary Hill,” written by Ruby Moody (BU —Sept. 1981).

Since Stoney’s death, Wilma Lee has recorded two albums for Leather Records of Roanoke, Virginia, “A Daisy a Day” and “The White Rose.” “Leather lets me select my own material for recording,” she happily reports. “For the first album I selected all of the songs but one, and for the second album I chose them all. I pick what suits my voice and style,” she adds. Says Leather Records president, Mike Haynie, “Artists of Wilma Lee’s experience can be trusted to select their own material. She knows what she’s most comfortable with.”

The Coopers’ early recordings have been lauded as “classics” and “masterpieces of old-time mountain music.” Some of their later efforts, however, were criticized for the apparent determination of record producers to move their sound “further and further [away] from real country music” through the overly prominent use of electric instruments, drums, and background voices. But with the release of her “A Daisy a Day” album, reviewers’ plaudits bordered on the ecstatic as they welcomed Wilma Lee back into the camp of true and unadulterated old-time music. “The album,” wrote one reviewer, “is a pleasant journey through the hallowed corridors of traditional music.” Wilma Lee admits that “After I lost Stoney I have tended to stay with the authentic music. Instead of hunting new songs I have stayed more with those good old songs.”

Besides Josh Graves and Bill Carver, a number of other prominent figures in the old-time country and bluegrass fields have been members of the Clinch Mountain Clan. Among them are fiddle player, Tex Logan; banjoists, Johnny Clark and Vic Jordan; guitarist, George McCormick; and mandolinist James (Carson) Roberts (BU—May 1980). The first banjo player (other than Wilma Lee) to perform with the Cooper troupe was Chuck Henderson, a North Carolinian who was hired in the early 1950s while the band was based in Wheeling. “Stoney felt we needed a banjo,” Wilma Lee states. He told writer Douglas B. Green (BU—March 1974) that he had liked the sound Bill Monroe had been getting with the banjo. “It was a snappy, sassy style,” he said. “It had some class.”

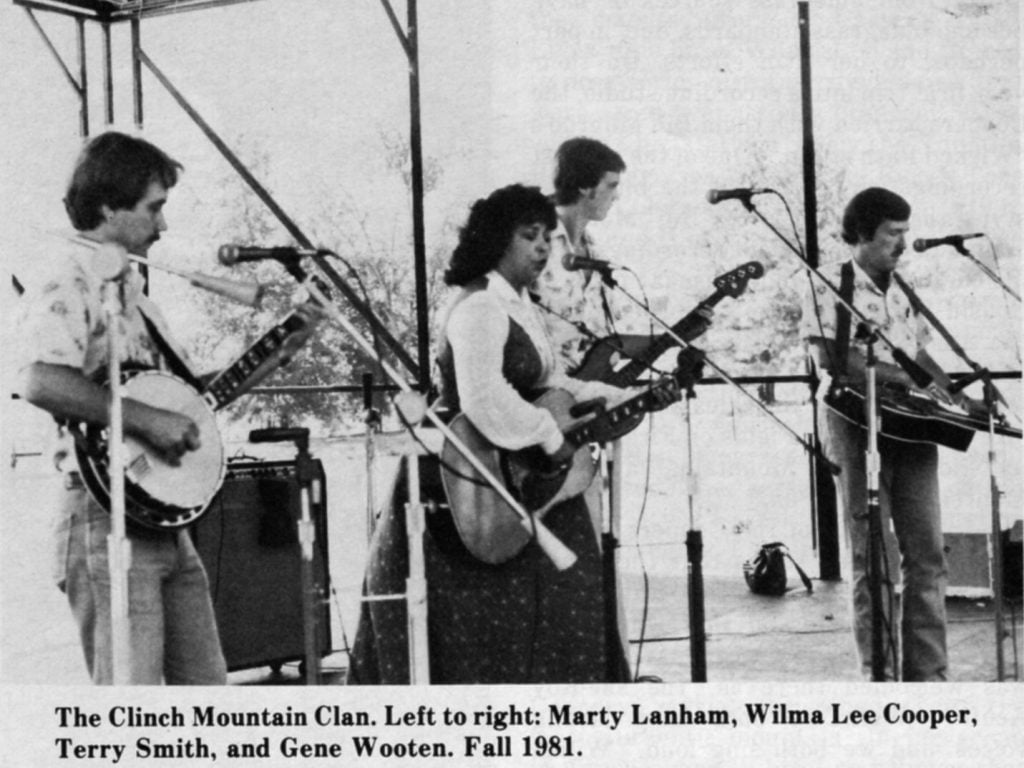

Wilma Lee’s current band consists of three musicians, all of whom come from the state of North Carolina. Gene Wooten plays Dobro and sings bass and baritone; Terry Smith plays bass and sings tenor; and Marty Lanham plays banjo. Tater Tate plays fiddle with the Clinch Mountain Clan on Grand Ole Opry appearances and sometimes accompanies the group when they go on the road. “I don’t hire musicians who drink or are on dope,” says Wilma Lee. “When you see my band,” she recently told a bluegrass festival audience, “you’ll know I have the kind of people I’d be happy for you to meet wherever we might happen to be.” Wilma Lee, herself, plays a strong rhythm guitar. Having long since laid aside the mail order instrument on which she learned, she now plays a D-45 Martin that was bought second hand. On occasion Wilma Lee plays banjo on some of her songs, using what she calls the “old flog style” in which she picks out the melody with her index finger.

Following Stoney’s untimely death, Wilma Lee was forced to make a choice between giving up her career or carrying on without her husband and professional partner of many years. She, of course, opted in favor of the later alternative.

Stoney, before his death, had been the person out front and the primary decision maker for the team. Now the full burden of maintaining a successful act has fallen on Wilma Lee. “It’s up to me now,” she muses. “I’m sure I don’t do it like Stoney would do it if he were living, but he’s not here, so I’ve got to do the best I can.”

“Stoney had a great foresight,” she continues. “It’s what they call ESP now. He could foresee things ahead down the road before they happened. He could see where the industry was going—how it was pointed. I remember back in the Wheeling days—around 1950—we were working high school auditoriums and the parks. One day he said to me, ‘I think we ought to try to work a drive-in theater. I see drive-in theaters being a big business for shows.’ So he booked one, and my goodness!” she exclaims, “we had every speaker filled up and no place to put the rest of the folks who wanted to get in. After that, we started working the drive-in theaters in the summer. Then other acts picked up on the idea.”

Bill Carver, former Dobro player with the Clinch Mountain Clan, for one, does not fear that Wilma Lee may not be able to hold her own as the brains, as well as the talent, of her outfit. According to him, she was never really very far removed from the decision processes, even while Stoney was alive, especially during the later years. “She can carry the show,” he declares. “She has a college education (a B.A. degree in banking from Davis and Elkins College of Elkins, West Virginia), and she’s a good manager.”

Carver recalls that in the old days Wilma Lee, when necessary, could even drive the band’s bus for hours without any apparent loss of vigor and exuberance. This vigor and exuberance that have long been the hallmarks of Wilma Lee Cooper, today, show no signs of abating. “I figure you’ve got to stay active,” she philosophizes. “It’s good for you. You just can’t sit down and not do anything. That will make an old person out of you. You have to stay busy.”

In addition to all of the other details of a show business career, Wilma Lee, since Stoney’s death, has assumed the task of doing her own booking. She now makes about a hundred personal appearances a year (not including the Grand Ole Opry and television specials) as compared to about twenty a year immediately prior to Stoney’s death. Because of declining health during the last few years of his life, Stoney did not feel up to the demands of so full a calendar of show dates. “But after I’ve lost Stoney,” Wilma Lee observes, “I’ve worked more and more every year, and this year (1981) has been my biggest year.”

Given her drive and her enthusiasm for what she’s about, there’s no reason to expect a slackening of Wilma Lee’s pace for a long time to come. As Bill Carver says, “She’s a great trouper. She loves the road; she loves the fans; she loves the music. That’s her life. She couldn’t function without show business, and she can keep going as long as she wants to.’

[Editor’s note: According to information in our files four of the five unreleased titles were: “Mathew Twenty Four,” “My Dream boat is Drifting,” “Things that Might Have Been” and “Blue Mountain Girl”]