Home > Articles > The Tradition > Nolan Faulkner

Nolan Faulkner

Detroit’s Miracle Mandolinist

The muzzle of the .38 Special revolver looked as big as the mouth of the Detroit-Windsor tunnel. Six shots rang out and four bullets struck him right in the gut. Forty years later, Nolan Faulkner remembered that cold Michigan night – “Lucky for me, he was a bad shot!”

Faulkner’s near-death experience on the streets of Detroit in 1979, and his subsequent lengthy recovery, earned him the name of “Miracle Man” among his musical peers, and it served as a reminder that the life of a musician in the big city was no bowlful of cherries.

The bluegrass scene thrived in Detroit for several decades following World War II, providing entertainment in bars and honky-tonks for the thousands of transplanted southerners who had moved north for better paying jobs within the automotive industrial complex. Recent books, such as Industrial Strength Bluegrass – Southwestern Ohio’s Musical Legacy (Fred Bartenstein and Curtis W. Ellison, eds.), remind us that during its formative years, the heart and soul of bluegrass music lay in these northern cities, a creative outlet and balm to the souls of those who were forced to leave their rural homes out of economic necessity.

Nolan Faulkner is one of the many musicians that helped make the Detroit bluegrass scene as vibrant as it was during those years. His instrumental, vocal and songwriting talents provided the extra spice that made otherwise good regional music exceptional. He played with a long list of bands, appearing on close to 50 different recording projects, often as a side man, but also as the featured artist. The fact remains that the legacy of such musicians is hard to track decades later, and we are fortunate to still hear his story, straight from the horse’s mouth.

Lee Nolan Faulkner was born in 1932 in the Bear Pen community outside of Campton, in Wolfe County, Kentucky, about 40 miles equidistant from Richmond, Winchester, and Hazard.

I was born in a rut after the Great Depression. Mom said we’d have starved to death if we weren’t on the farm, and we would have. I remember walking the roads every morning in our bare feet looking for road kill. They used to say that Wolfe County was the poorest county in the United States, except for one in Alaska somewhere. There wasn’t no industry there, the vein of coal was about a foot thick, and there wasn’t no railway through there. It was pretty bad country to live in.

Music became an outlet for Nolan in 1946 after an aborted attempt to run away from home, and he first played “Maple on the Hill” on the guitar. His half-brother John ordered a mandolin by mail, and he cut his teeth on tunes like “McKinley’s March” and “Chinese Breakdown.” Both WCYB and WSM live broadcasts were sources of mandolin inspiration, via the playing of Pee Wee Lambert and Bill Monroe. His first band experience came playing local pie suppers with the King Boys.

When Nolan was about 16, he replaced the guitarist in the Powell County Boys and played as a trio with Harold Booth and Ramah Boyd.

We played on the Kentucky Mountain Barn Dance at the Clay Gentry Arena in Lexington, that was a pretty big thing then. Had Flatt and Scruggs on it, sometimes they had the Stanleys on it. Did you ever hear of Ray Myers? He didn’t have any arms and he played a resonator guitar with his feet. On stage, he’d open a bottle of pop, drive a nail. And once, we played at a high school where the door was next to the stage, and me and Ramah and Harold went out to smoke a cigarette, and when we went out we closed that door, but it locked when you closed it. I said “Boys, how are we going to get back in there,” there wasn’t nobody in there but Ray backstage at that time. And we knocked on the door and he come and opened it with his feet.

They let us play on that Barn Dance that night, but it was tough. That was back when the Davis Sisters was first startin’ out, Skeeter and Betty Jack. And they had come down there, maybe for an audition, or for a guest. It was back when “Poison Love” was popular. We had it all worked out – the tunes “Poison Love” and “Uncle Pen.” We was backstage, you know. And Skeeter goes, “Aw, I’m dreadin’ to go out there. We gotta go out there and do that “Poison Love.” And that was the number that we was gonna do. So we had to figure out another piece to do real quick. I’ll never forget that.

About 1950, he joined Dallas Riddell and the Kentucky Troubadours as a guitarist, and he learned a lot from mandolin player Johnnie Johnson, who taught him two-string harmony picking, and tunes like Arthur Smith’s “Mandolin Boogie.” Life in the band was not without its drama, however.

Old Johnnie cut Dallas one night, hit him outside with the side of a knife. Dallas was dippin’ on the kitty, and I think Johnnie smelled a mouse. But old Dallas didn’t press charges against him. The next morning they got him out of jail and bought him a bus ticket and sent him home.

The band would play over WVLK radio from the studio of the Glyndon Hotel in Richmond, Kentucky, and later had extended gigs at places like the Crown Café and Bob and Ray’s Taproom in Hamilton, Ohio. There they would stretch their limited resources by living on bologna and cheese sandwiches and sleeping in old cars in a local junkyard. Their bass player at the time was Bryant Rogers, who had been a member of Silas Rogers’ original Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in the mid-1930s, a band that also included David “Stringbean” Akeman, who later went on to greater fame as banjo player and singer with Bill Monroe. He also “carried along” with him the Rogers’ original tune “Rocky Road Blues”.

Bryant was the bass player and the comedian, he was a clown. They said part of his act with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers was lettin’ a guy named Ken Maynard—he was pretty popular in the silent cowboy movies at one time—this guy was a sharpshooter, and Bryant would let him shoot cigarettes out of his mouth onstage. They’d do stuff like that to draw a crowd. Old Stringbean was with ‘em then.

Nolan would periodically visit his brother Jim, who had previously moved to the Brighton, Michigan area to work at the American Aggregate gravel pit. He would pick up some extra work there, and made enough money to afford a new Silvertone mandolin. After trying his hand at farming on the old Bear Pen homestead for a couple of years, Nolan headed north for good and worked at the same gravel company for the next 15 years.

Early on in Michigan, Nolan became familiar with Red Ellis, who was then a DJ working out of WHRV in Ann Arbor. He attributes much of his additional progress on the mandolin to the assistance of Ellis’ mandolinist, Billy Christian. He ended up playing with Ellis, off and on, and recorded two Christmas songs for Ellis’ Pathway Records in 1963, as well as being featured on the song “Two Little Rosebuds” on Ellis’ 1964 Starday LP Old Time Religion Bluegrass Style.

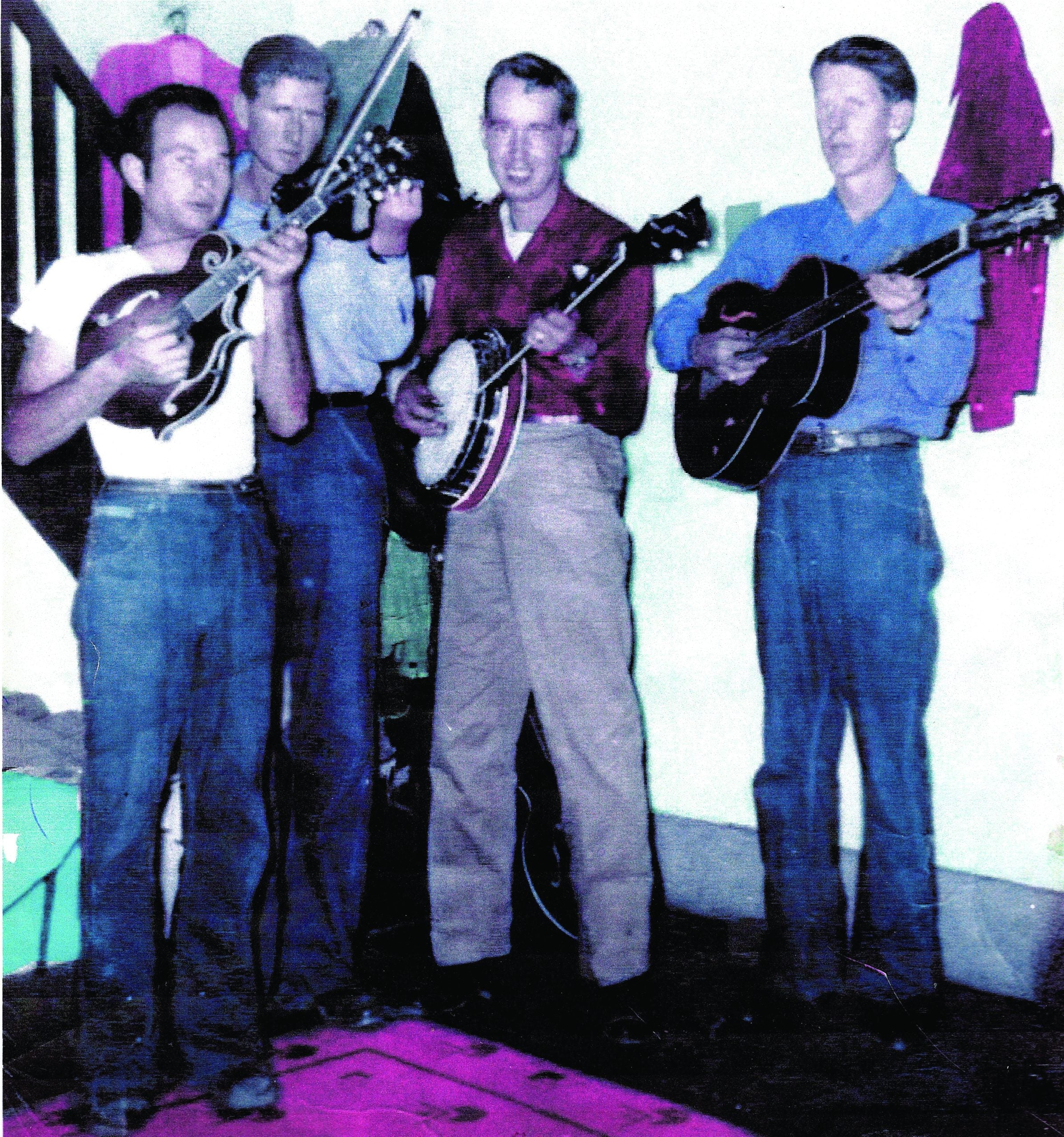

Nolan released several additional 45 rpm recordings on small labels such as Sun-Ray and Happy Hearts in the 1960s, and they included southern ex-patriots such as Bill Carpenter (Dobro), Ed Carroll (guitar), Willard Elkins (banjo), Virgil Shouse (fiddle) and Fred Cottingim (bass). During the late 1960s, his band The Big Sandy Boys also included University of Michigan students, guitarist Doug Green and fiddler Andy Stein, later of “Riders in the Sky” and “Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen” fame, respectively. They recorded for Tommy Crank’s IRMA Records – “Alimony Blues,” one of the good original Faulkner songs released at this time, also signaled a change in lifestyle for Nolan. A divorce and six children to support dictated a move in 1971 to a new factory job and an apartment in the more affordable downtown Detroit, where the rent was cheaper, and bologna, to quote the lyrics, was only “ten cents a pound.”

By the early 1970s, larger record labels that focused on regional Michigan bluegrass and gospel music had sprung up, especially Jessup and Old Homestead, and Nolan’s musical talents were now in greater demand as his mandolin skills had become more refined. I asked multi-instrumentalist and bluegrass historian Matteo Ringressi, of Italy’s Truffle Valley Boys, for his analysis of Nolan’s distinctive style as a mandolinist.

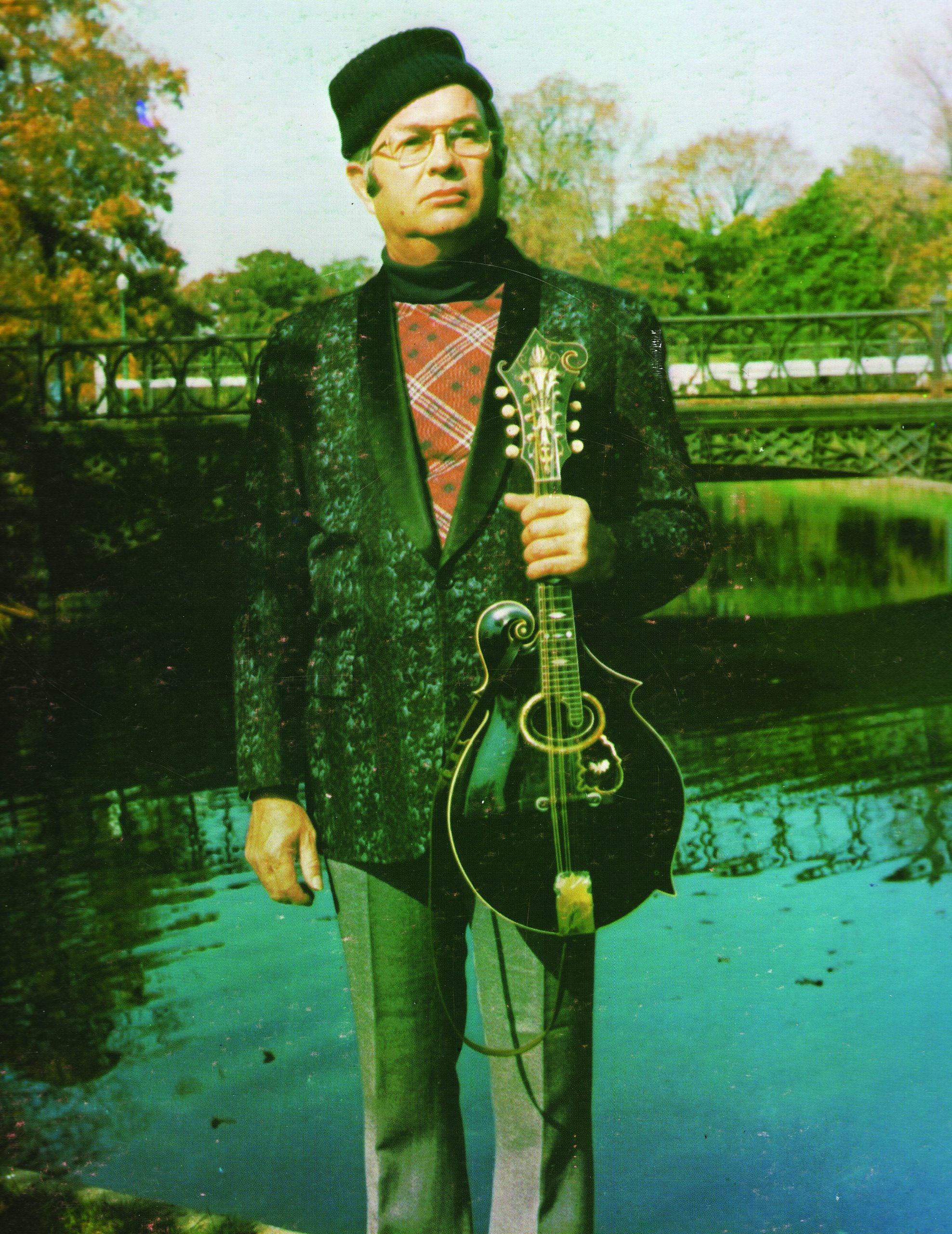

Nolan Faulkner always struck me for his personal and highly distinctive mandolin style. Even early on, as his 1960s recordings with Red Ellis and Bill Carpenter testify, he had already started applying his own sensibility to the instrument. His left hand was capable of outlining beautiful, poignant passages as well as bluesy licks reminiscent of Bill Monroe, while his right hand was smooth and solid, and his phrasing airy yet incisive. His use of “slides” was extremely effective as well. In my estimation, he’s one of only a handful of mandolin players that knew how to fully explore the tonal complexity of his instrument (a 1905 Gibson F4 Artist model), with ringing, crisp highs and deep, woody lows, and rich in sustain. As a lover of oval-hole mandolins in Bluegrass, that tone is what made me gravitate towards Nolan’s playing at first.

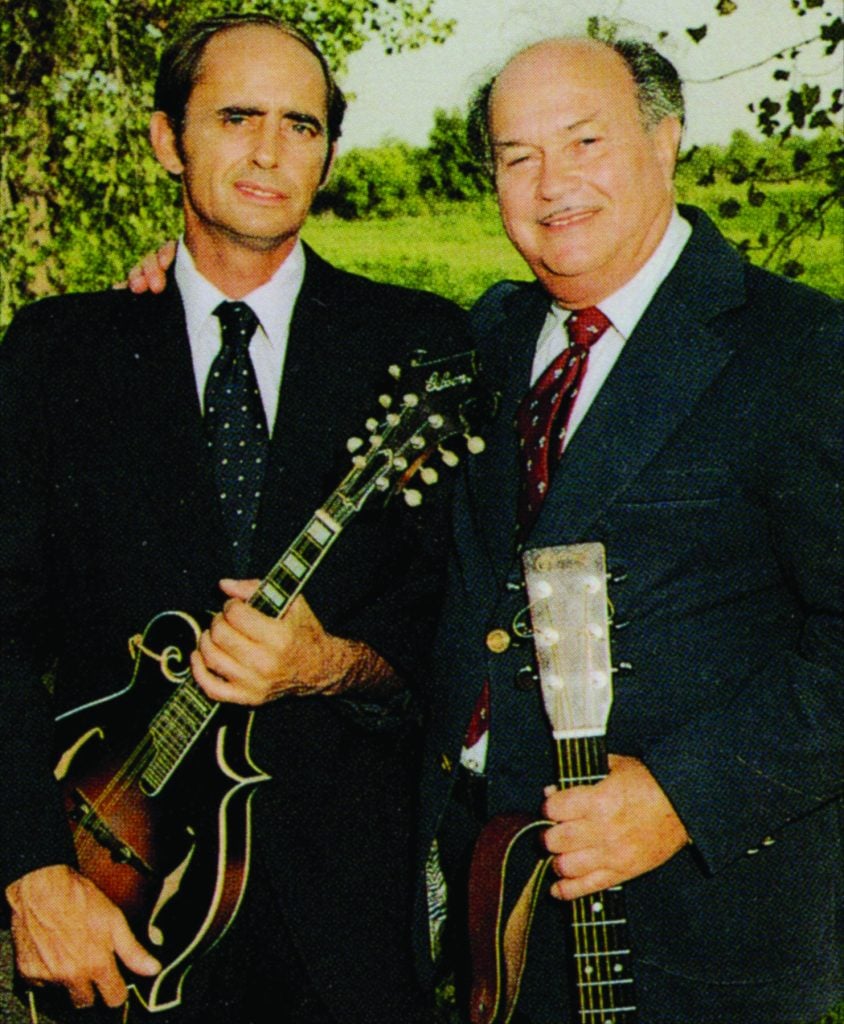

About the same time, Nolan began his legendary tenure with the Miller Brothers—Earl, James and Charlie—after meeting Earl at one of the eastern shore taverns/hillbilly hangouts in Walled Lake, Michigan. The career of the Miller Brothers was recently documented in Bluegrass Unlimited (September 2020), so we won’t chew that cabbage again here. Suffice it to say that the band went on to record their first LP for Jessup Records (Teenage Angel in Heaven) and several more for Old Homestead Records before calling it quits. Compared to the regional music recorded by similar native Kentuckians, the Miller Brothers music had an older and more archaic feel to it. If you like bluegrass music that even makes Ralph Stanley sound like a city slicker, you should check them out.

Nolan began a lifelong friendship with Jim Miller when he met the Miller Brothers, and their musical collaborations extended well beyond the band’s formal break-up. He considered Jim Miller’s voice, along with fellow Wolfe County musician Roland Dunn, among the most unique in bluegrass music.

His voice is equal to someone like Bill Monroe or Billy Gill. You couldn’t hardly record him, keep the recording level out of the red. Beautiful voice…it would almost break a glass. But you don’t know where it’s coming from. His neck weren’t as big around as a Coke bottle. I worked with a lot of singers, but Jim had one of the highest voices.

During the mid-1970s, Nolan mostly stuck to playing gigs with the Miller Brothers, but was in great demand as a studio musician for Old Homestead Records. His long list of studio album credits (often unlisted) included Lee Allen, Wade Mainer, Mike Lilly and Wendy Miller, Bob Smallwood, Larry Sparks, Joe Meadows, Clyde Moody, Charlie Moore, John Hunley, and others. He also released his solo Old Homestead LP, The Legendary Kentucky Mandolin of Nolan Faulkner, in 1976, an album full of original tunes that demonstrated Nolan’s mastery of the mandolin, as well as the influence of blues and gypsy music on his playing style. “The Blind Fiddler” was a tune on the album taught to him by Owens “Snake” Chapman, who had in turn learned it from legendary blind West Virginia fiddler Ed Haley.

The downtown Detroit shooting in 1979 had a dramatic impact on Nolan’s life. After six weeks in Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, he was flown to the University of Kentucky hospital in Lexington for 6 more weeks of recuperation, then another 15 months at Cardinal Hill Rehabilitation Hospital, where he learned to walk again. One of his unique and original songs, “Afraid to be Afraid” described his fight to survive on the night of the shooting.

This young therapist said to me, “You’re afraid to be afraid.” I said, Man you are crazy. But it was true. I was afraid of the thought of the dreadful…what could happen to you. Then I wrote the song, fooled with it.

Nolan returned to Detroit and attempted to resume factory work, but it didn’t work out, so he mostly returned to a life of music. He played regularly with John Hunley and his Lost Kentuckians at their home base of the Jack Daniel’s Lounge in Lincoln Park, and traveled and recorded with Roy McGinnis and the Sunnysiders, Robert White and the Candy Mountain Boys, and Jim Miller.

The late 1970’s to the mid-1990s marked a period of popularity in the release of cassette tapes in bluegrass. They fit a niche–they were relatively cheap for record labels to produce and manufacture in limited and incremental quantities, and easy for customers to play in their cars and carry around, but they were always more ephemeral than records. Before long, they were lost or broken or wrapped around the capstan of your tape player. As a result, much of Nolan’s recorded output during this time frame is hard to find today. Especially noteworthy were two additional cassette recordings with Jim Miller, Land of the Thoroughbred (1990) and From the Heart of Bluegrass (1992), that featured many original songs and continued the fine tradition of first-class music put out by the duo with the Miller Brothers. The 1990s also produced an unusual set of 50 original songs on five cassettes written by Hallus Sargent, a coal miner/poet/Ford Motor Co. parts handler originally from Verdunville, WV. Nolan was hired by Fay McGinnis to put the words to music, and with the help of local musicians like Roy McGinnis, Virgil Shouse, Charlie Flannery and others, to commit the songs to tape.

Nolan continued to play with Detroit area musicians over the ensuing years, including Long Tall Lou, and with the Cass Valley Ramblers (Ben Luttermoser, Rachel Price, and Dana Cupp), although no commercial recordings resulted. Nolan eventually retired to be close to his daughter near Paducah in western Kentucky, where he still lives and loves to talk about music. He has left an impressive, if sometimes elusive, quantity of recordings that mark a period when bluegrass musicians could still remember the hard times that they sang about. Looking back over a long life, in which most of the musicians that he remembered had now passed away, he had some parting advice:

Let me tell you something, before you get old—if you’ve got the money, and you want something, buy it. And if you want to go somewhere, go. Because when you get older, you’ll look back and say, why didn’t I do that. So don’t deprive yourself of something you can do —just do it. And if you’ve got a good woman, be good to her if she’s good to you. And if she ain’t, why, you’ve just got to roll with the waves.

Hank Edenborn co-founded White Oak Records with banjo great Don Stover.