Home > Articles > The Archives > Original Five-String Flathead Prewar Gibson Banjos

Original Five-String Flathead Prewar Gibson Banjos

Three Articles by Jim Mills that appeared in Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine in March 2002, August 2003, and November 2004

Article #1—Something Special

Written by Jim Mills

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

March 2002, Volume 36, Number 9

The history on this banjo is pretty well recorded. As far back as I can trace, Mr. Mack Crow was the first owner of this Gibson banjo sometime in the late 1930s or early ’40s. Mack Crow was quite famous in his day. He was a pioneer of the three-finger picking style of North Carolina and was also an early influence on Earl Scruggs as mentioned in Earl’s instructional book. Mr. Crow was billed as the “Banjo King Of The Carolinas” and had a popular vaudeville touring act in the 1920s and ’30s. From early photos of Mr. Crow, it is believed that he was more than likely an endorser for the Gibson Co., and this banjo was custom ordered from them. Mr. Crow, advancing in age, sold the banjo to Avery Aiken—a very good banjo player of local fame from Statesville, N.C.— sometime in early 1952 where it remained until April 2001 when I purchased it from Mr. Aiken’s widow.

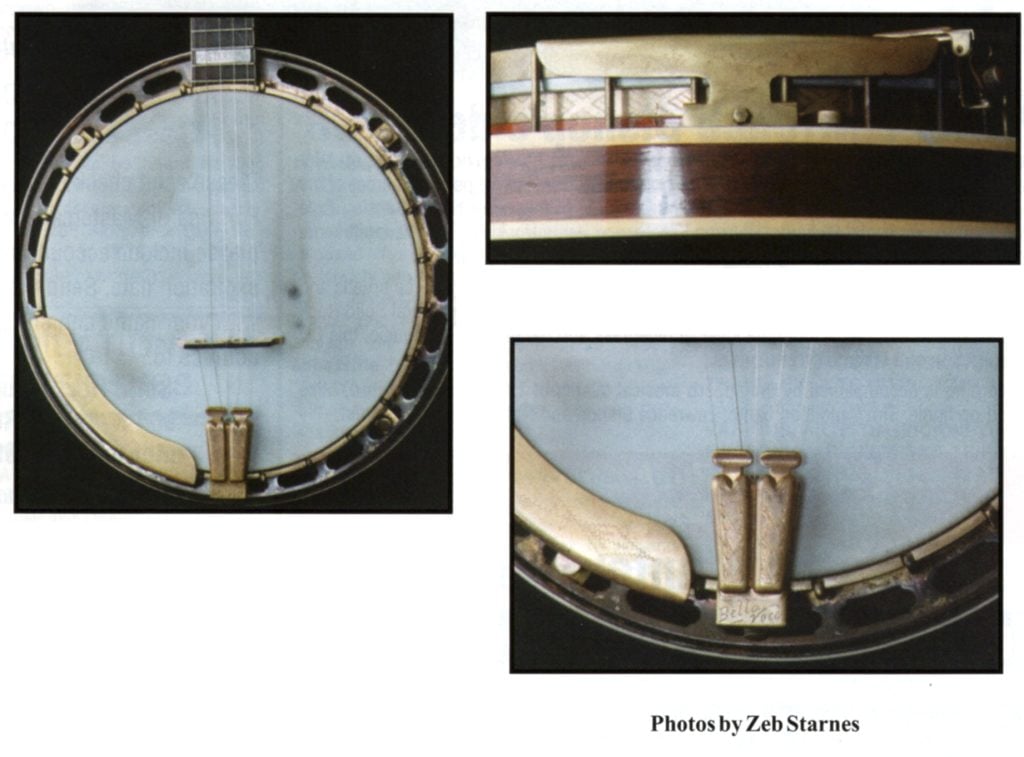

Its serial number, 453-2, is an original flathead five-string RB-75 with factory original gold-plating—the only one known to exist. In the late 1930s, Gibson was phasing out regular banjo production and bringing in a completely new line of banjos known as “top tensions.” They were designed to make it easier to adjust the fickle calfskin heads of the period from the tension hoop rather than having to remove the resonator.

They hit the market with the 1937 Gibson catalog. Two of the world’s most respected prewar Gibson banjo authorities, George Gruhn and Curtis McPeake, have both thoroughly examined this banjo, and both have documented it as “original” inside and out and agreed that this one-of-a-kind RB-75 that would have been made around [1937-38]. It seems that Mr. Crow more than likely ordered a gold-plated banjo but didn’t want a top tension, and serial number 453-2 is what he got. There were no gold-plated regular banjos being produced at this time. The Granada style 6, 5, Bella Voce, and Florentine were all out of production. The only gold-plated banjo being made was the RB-18, the new top-of-the-line top tension. Prewar flat-head scholars have come to the conclusion that since the RB-75 was the only regular banjo in production, and it being a nickel-plated budget model, the Gibson factory proceeded to build this banjo with whatever gold-plated parts left from previous out-of-production models. It features a Granada engraved armrest, a high profile style 6 engraved flathead tone ring, a Bella Voce engraved tailpiece, a gold one-piece flange, gold Grover pancake tuners, tension hoop, brackets, and nuts. The rest of RB-75 ser. #453-2 is standard catalog all the way, with an uncut Mastertone label inside the rim, standard 75 inlay, mahogany neck, and resonator.

Vintage Gibson banjo gurus have for years debated the difference in the sound of a prewar gold-plated tone ring and a nickel-plated tone ring of approximate vintage. The gold-plating on the tone ring is said to add a certain sweetness to the tone, and this ‘something special’ is what Earl Scruggs apparently heard when he traded Don Reno a nearly new nickel- plated RB-75 for Don’s very worn Granada which Earl still plays today.

Banjo scholars have also studied the difference in sound of the two most popular woods used in banjo neck construction—mahogany, which was standard on the RB-3 and RB-75, and maple, which was standard on Granadas and several other models. In 1958, Earl Scruggs commissioned Nashville, Tenn., luthier J.W. Gower to build a mahogany neck for his Granada with prewar-style hearts and flowers inlay. This combination of gold-plated tone ring and mahogany neck produced one of the very best tones ever produced by man or banjo. Earl recorded the “Foggy Mountain Banjo” album with this combination which is generally regarded by most Scruggs-style players as the Holy Grail of banjo tone, timing, and taste.

Earl also recorded the “Live At Carnegie Hall” record and many others with this combination of gold tone ring and mahogany neck. It makes you wonder, did Earl know something no one else did when he ordered that mahogany neck back in 1958? I don’t know what it is, but there’s definitely something special there, and ser. #453-2 is the only factory-produced gold-plated, mahogany, flat-head combination known to have been made, and I’m very thankful to Mrs. Aiken (now Mrs. Hill) for selling it to me.

I’ve been fortunate enough to have owned three other original five-string flatheads. but this one’s got something on all of them! I almost forgot. An old friend of Mr. Aiken’s told me that Earl Scruggs had tried to buy this banjo from Mr. Aiken back in the ’50s, but he wasn’t interested in selling. Isn’t that the coolest thing? Maybe Earl heard something special way back then, before he ordered his own mahogany neck!

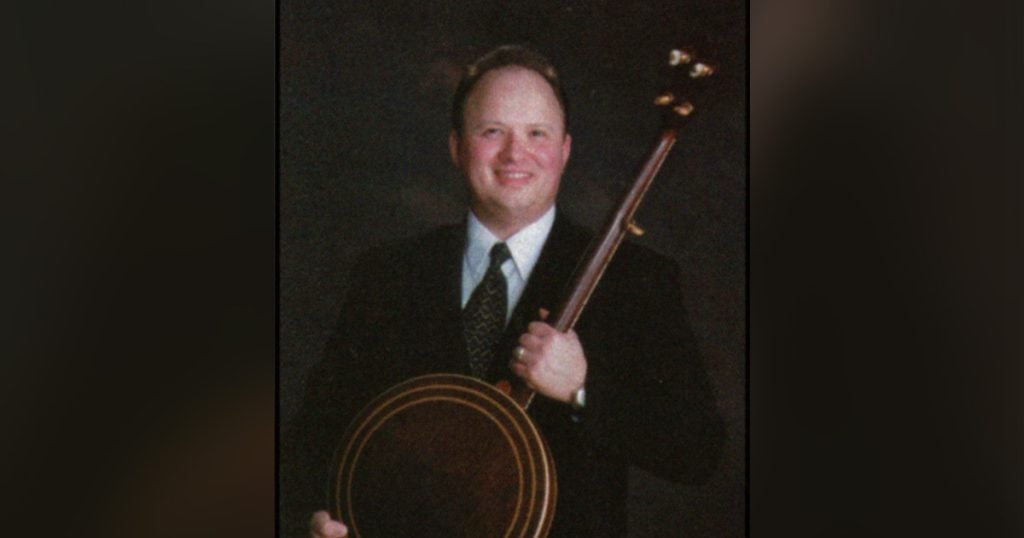

Jim Mills is a Sugar Hill Records recording artist, three time IBMA Banjo Player Of The Year, and a member of Ricky Skaggs band Kentucky Thunder.

Article #2—The Story of One Man, Two Banjos, And Why We All Want A Prewar Flathead Five-String Gibson Mastertone Banjo

By Jim Mills

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 2004, Volume 39, Number 5

It has been estimated from serial number totals that only 240 or so original prewar flathead five-string Gibson banjos with one-piece flanges were produced between 1930 and 1944. It must be realized that some of these banjos are now approaching 75 years old and many have been lost to floods, fire, and other acts of nature. Sadly, several have also fallen victim to butchers who claim to be repair persons. These instruments also are lost forever, ruined beyond repair. With an estimated ten percent lost or destroyed, that leaves 216 supposedly still existing, making them rarer than a Stradivari violin.

For sure, there has never been an abundance of these great old banjos, and the number can only get smaller as time goes by. To find one in any condition is to find a prized possession, but to find one in 100% original, unaltered condition is now nearly impossible. For some reason, banjo players have always loved to tinker with their instruments. Since banjo parts from several companies are quite interchangeable, and a banjo is half nuts and bolts, they lend themselves to being altered or changed more than say a guitar, fiddle, or mandolin. That’s where a lot of the problems occur that we see today in vintage Gibson banjos. The owner at some point wishes to change their tuners or tailpiece, or try a new tone ring or even a new neck, or possibly refinish the banjo in the backyard. Every time this happens, another little piece of originality is gone, sometimes forever.

Of the 200 or so original flathead five-strings estimated still in existence. I’ve been able to locate 74. I have owned five of these extremely rare instruments and have personally seen and played 47. Of the remaining 27, I either know their pedigree or information about them that comes from a respected source, in which I trust very few. I won’t say I’m an expert, but I will say I’m a scholar of the prewar Gibson five-string flathead banjo.

You can imagine my excitement then, when I learned of one only a couple of hours away from my home. My dad and I decided to go take a look at this truly rare banjo. The funny part is that I had been within five miles of this banjo a hundred times in the last fifteen years and had never known it existed.

When I finally got to see it, I was amazed by the originality of this instrument. After 65 years, it not only resided in its original redlined case, but it retained its original friction fifth-string peg and factory headguard, not an easy piece to find as they were usually lost or discarded over the years. Inside the case was the bracket wrench and an original Gibson bridge. The owner also had many photos of him and the banjo from the ’40s, which are nearly as rare as the banjos themselves. This banjo was 100% original and completely unaltered!

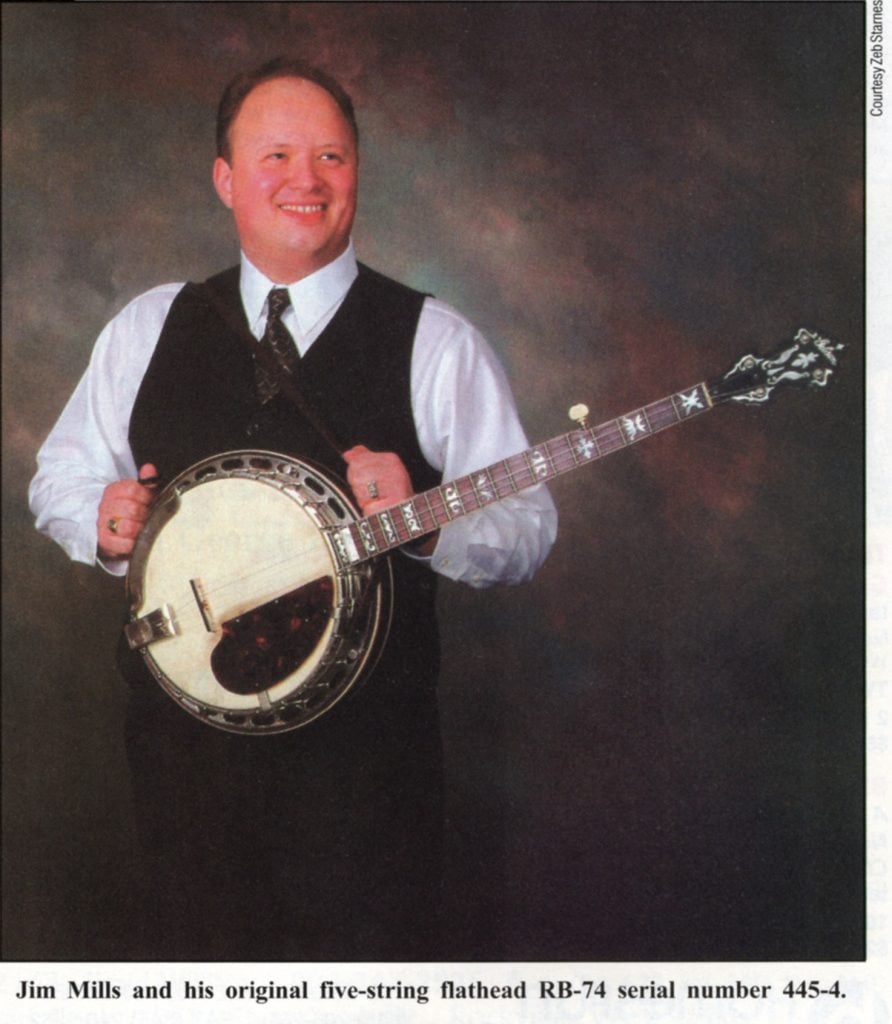

After hours of negotiations and a lot of money, I was able to purchase this banjo from a man who had owned, played, and cared for it since he was 16 years old. He was now 71. For 55 years, he had the extreme pleasure of owning a Gibson RB-75, serial number 445-4—an original flathead five-string. The man proceeded to tell me the life story of this banjo up to the present. I discovered, in the beginning, that it was shipped out of Gibson’s Kalamazoo, Mich., plant on October 11th, 1937, and ended up at Beckley Music, a store in Beckley, W.Va. It was purchased by its first owner, Mr. Walker, who took it home to nearby Rodell, W.Va.

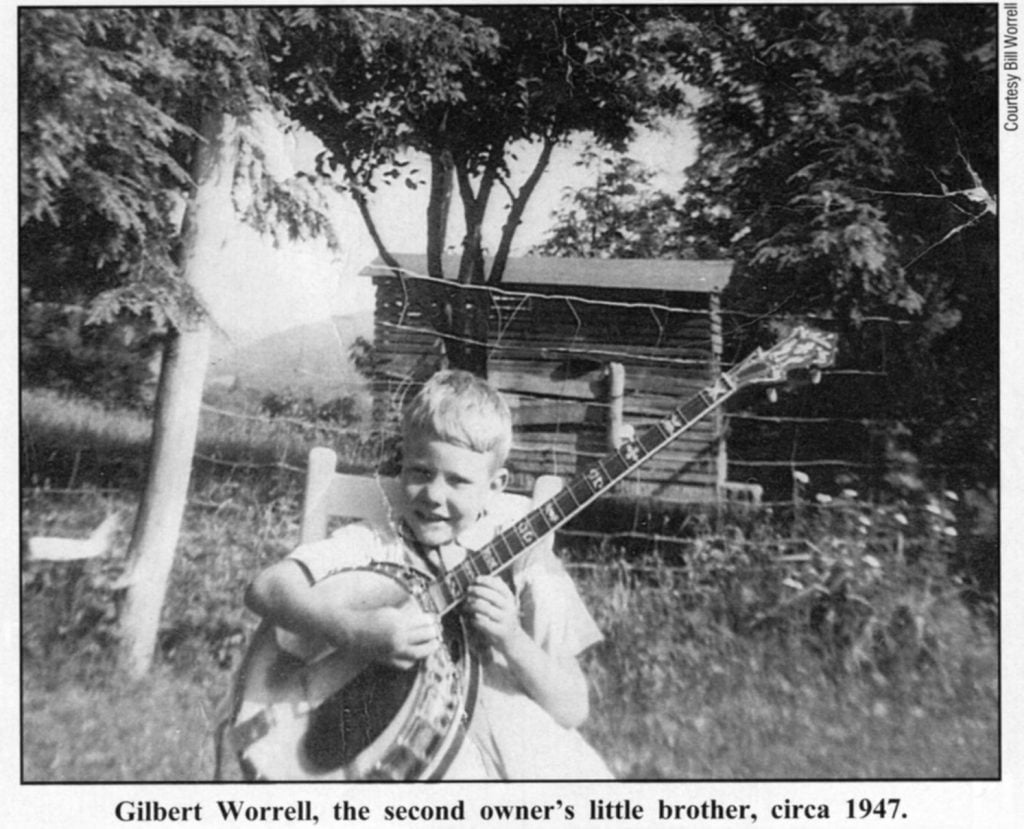

Ten years later, Mr. William M. Worrell, in September of 1947, was able to purchase his nearly new dream banjo for a then-costly sum of $100 directly from the original owner, Mr. Walker. Mr. Worrell told me he was 16 years old, working at a sawmill making 75 cents an hour.

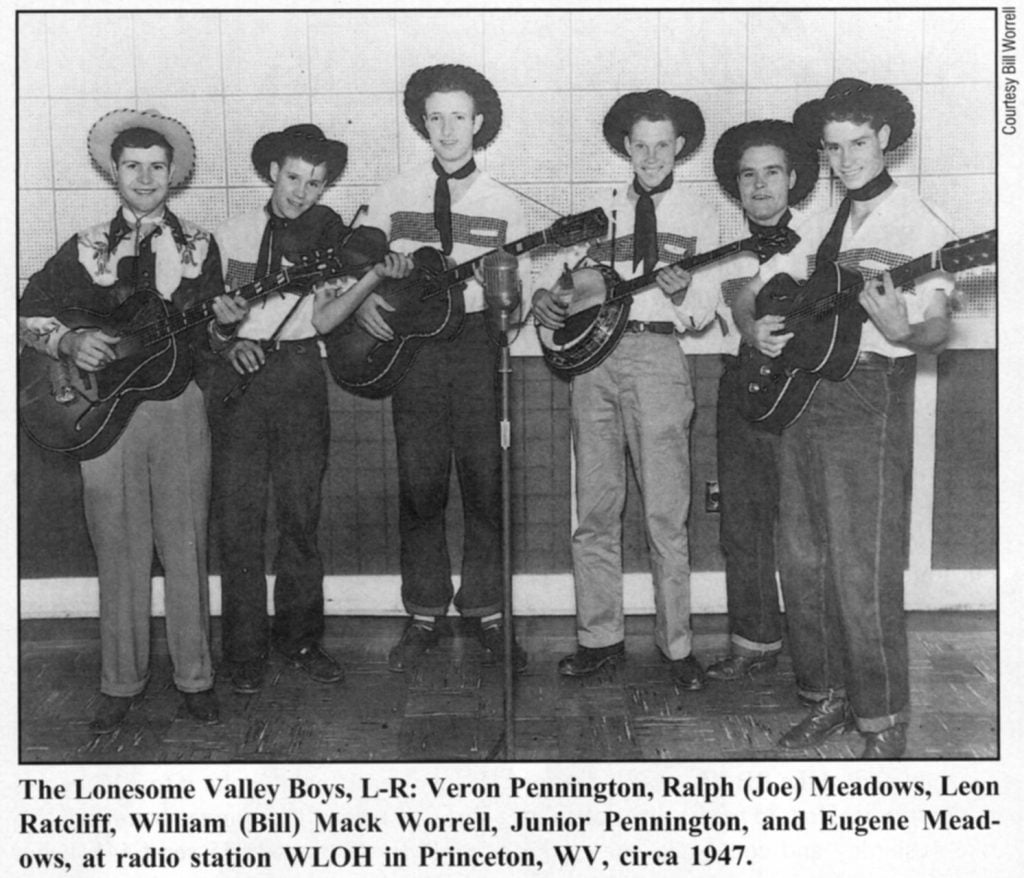

Radio station WHIS in nearby Bluefield, W.Va., was, in the late 1940s, a hotbed for this newly created music, later to be called bluegrass. Two up-and- coming youngsters, Bobby Osborne and Larry Richardson, had a job performing there every day. While there, Larry Richardson borrowed RB-75 ser.# 445-4 for a short period and tried to trade another banjo for it, but Mr. Worrell was quite happy with his newly acquired Gibson banjo.

A few years later, a band that was to become legendary as one of the pioneering bands in bluegrass began performing regularly on WHIS. This band, the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, recorded for the prestigious RCA record label in Nashville, Tenn. In the early ’50s, the lineup included Ezra Cline on bass, Paul Williams on guitar. Curly Ray Cline on fiddle, and the Goins Brothers (Ray on banjo and, later, Melvin on guitar).

Ray, one of the great early three-finger-style banjo players, knew of this Gibson Mastertone way down in the country and borrowed the banjo from Mr. Worrell’s dad, while the younger Mr. Worrell was in the Navy. It was at this time, while on loan to Ray Goins, that a very young (11 years old) Sonny Osborne saw and played the RB-75 ser.# 445-4 for the first time. He told me he remembers it like yesterday and could take me to the very house and room where he first saw the banjo, if it still existed. It must have made quite an impression for him to have remembered it for over fifty years.

Ray Goins recorded eight sides (including “My Brown Eyed Darling” and “Nobody Cares”) with this banjo in 1952 for RCA with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers. Some of these are now bluegrass classics.

When I look at this banjo, I have to think of how many miles it must have traveled in that redlined case, in the heat and cold, in the trunk or backseat of some old 1930s or ’40s automobile, on dirt roads of West Virginia, and two-lane roads of Virginia and Tennessee that hadn’t yet become interstates. It’s a wonder this banjo survived it all.

It seems after the 1950s, RB-75 ser.# 445-4 led a pretty easy life. Through the ’60s and ’70s, it was played regularly by Mr. Worrell, but sometime in the ’80s, after building himself a new “parts” banjo, he decided to semi-retire this old jewel, or at least just bring it out every now and then. Whenever he would take it to a bluegrass festival, many of the great banjo players would try to buy RB-75 ser.# 445-4, but Mr. Worrell wasn’t interested in selling. I am very thankful that he decided to sell it to me, on that cold November day that I will never forget.

By the way, this banjo also came with an extremely rare inlay pattern for an RB- 75—a full flying eagle pattern. This inlay was usually reserved for the next higher grades, RB-4 and Granada, but anything was available as a custom option from Gibson. I know of several RB-75s with the so-called “Reno” pattern, named after Don Reno’s banjo which has a flying eagle fingerboard and a standard RB-3 or RB-75 peghead inlay. I’ve talked to several Gibson banjo scholars and all we can come up with are three examples with this full flying eagle inlay.

I can’t say what lies ahead for RB-75 ser.# 445-4, other than that I am very grateful for the opportunity to own and play this monster of a banjo. I’ve got the old Rogers calfskin head on it now and will more than likely do some recording with it so other people can experience the unexplainable tone that only these old original banjos have.

That’s the life of this banjo, 66 years after it left the factory. I hope it has another 66 years that will be as exciting as its first, with many more to come.

Jim Mills is a Sugar Hill Records recording artist, a three-time IBMA Banjo Player Of The Year, and a member of Ricky Skaggs’ band, Kentucky Thunder.

Article #3—The Life Of An Original Five-String Flathead Prewar Gibson Banjo

Written by Jim Mills

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 2003, Volume 38, Number 2

Nearly anyone who has studied the history of bluegrass music at any length has at least heard or read of a man named Snuffy Jenkins and how he helped pioneer the three-finger style of banjo playing in North Carolina in the early 1930s. There have been many articles published on this man and this subject, including several over the years in these pages. You’ve also heard and read that he was an early influence to Earl Scruggs and Don Reno, the two most influential men in bluegrass banjo playing as we know it. Snuffy claimed to have taught neither man anything, but admits that whenever he performed near the hometown of either of these boys, they would nearly always show up and spend some time with him. In this era, it was very common for banjo players to perform comedy on stage, and Snuffy was a fine comedian. But in this article, we will only focus on his banjo attributes. Being a banjo player myself, born and raised in the heart of North Carolina not far from where all this is known to have taken place. I’ve always had a huge interest in studying anything relating to this subject.

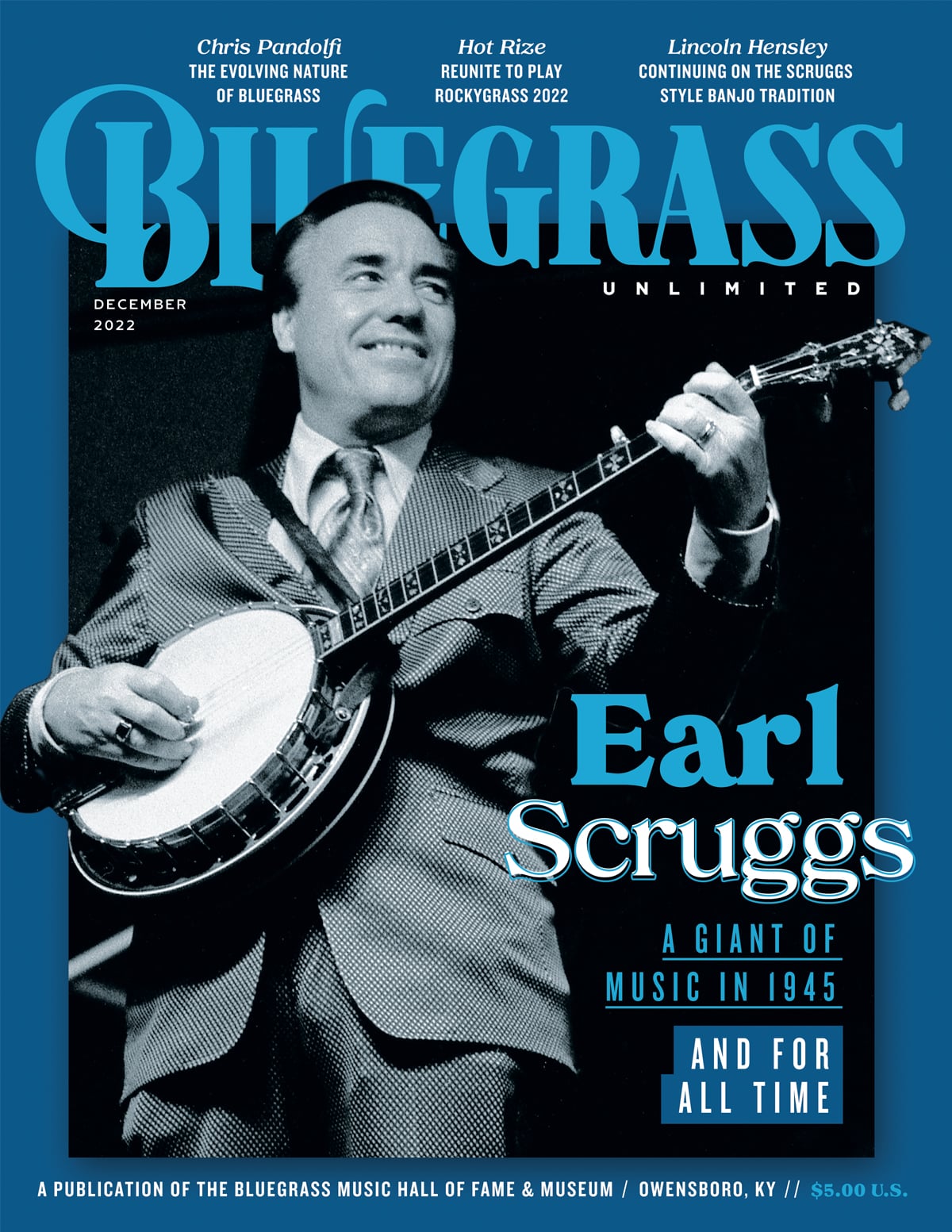

Let me start off first by saying this article is not intended to dismiss or cast any kind of shadow on the contributions of either Earl Scruggs or Don Reno. These two men are more than deserving of every accolade bestowed upon them and more. Earl Scruggs is the sole reason I wanted to play a banjo in the first place, and I would never say or do anything to undermine either man’s importance to our music in any way. I don’t think anyone in history, past or future, will ever do as much to further the five-string banjo as Earl Scruggs. All that being stated, I would now like to point out a few interesting things about the man. Snuffy Jenkins, and his banjos that, as far as I know, have never been printed before.

To understand fully the whole scope of this subject, we must go back to around the year 1920. It was somewhere around this time in the small area between Rutherford and Cleveland counties in North Carolina that several local amateur banjo players began experimenting with what is now known as the three-finger style of banjo playing. I realize that others, such as a few classical banjo players, are thought to have dabbled in this style earlier in different locations, but for now, I’ll discuss the style that is similar to what we know today. This style, as far as anyone can trace, came about in the earlier ’20s and was entirely from the above-mentioned part of North Carolina. The two men that are most frequently recognized as the first to play this style with any proficiency are Smith Hammett and Rex Brooks. A few others are Mack Woolbright, Clay Everhart, and Mack Crow. All these men were located within less than a 75-mile radius of each other at the time, and it’s easy to see how this new style could have evolved in just a few years.

Now, back to Snuffy Jenkins. Dewitt “Snuffy” Jenkins was born October 27th, 1908, in Harris, N.C., right in the middle of where all this was going on. Snuffy was nearly grown when this new style began to take shape and show up in the area. He and his brother Verl began playing some with Smith Hammett and Rex Brooks at local dances and other gatherings. Verl played fiddle and Snuffy played guitar with the group for a short while, but Snuffy soon decided to switch to banjo because the guitar was so hard on his fingers. Snuffy admits that this was where he learned the three-finger style of banjo from Hammett and Brooks. Snuffy also stated that while they were very fine players. Hammett or Brooks didn’t use metal fingerpicks until much later. They used only a thumb pick and their fingernails and would play until their fingers got sore. After getting a job on the radio with a full band. Snuffy found he needed to be heard consistently over the other instruments such as the fiddle, guitars, and vocals, and fingerpicks were his answer. Playing the five-string banjo today with a thumb pick and two metal fingerpicks is something we just naturally take for granted as the norm, but this just goes to show how early this man was unknowingly pioneering another aspect of our style of playing. Another pioneering effort of Snuffy’s was having another instrument, besides the fiddle, stepping in and taking a break in early hillbilly or old-time music, bridging the gap to what would eventually become bluegrass music. He was one of the first to take a solo on the banjo on faster fiddle tunes and breakdowns, as the fiddle had been used exclusively as the lead instrument on this type of song in most all the earlier string bands. It’s hard to imagine now, but back then, the banjo was used more as a rhythm instrument than a lead.

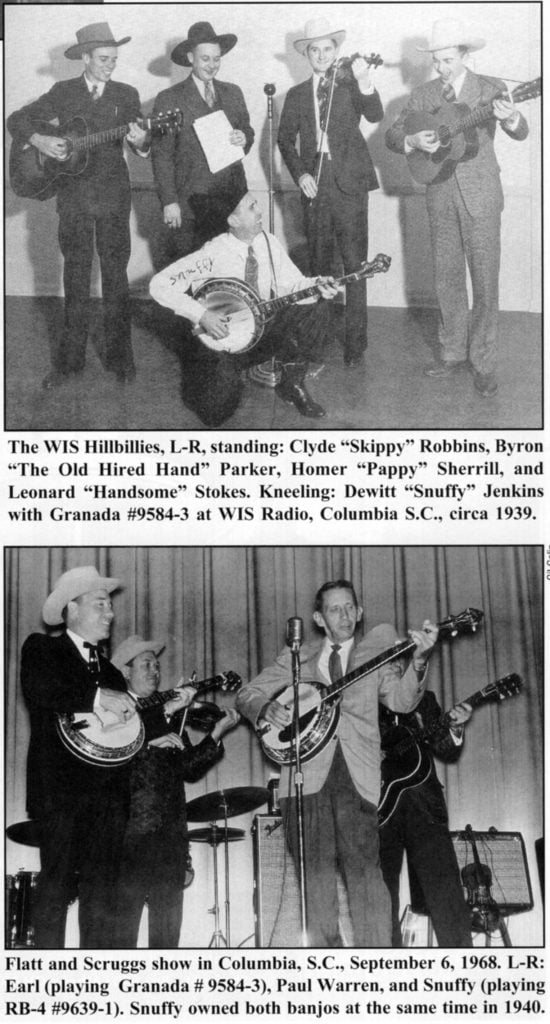

It was 1927 when Snuffy, now playing the three-finger style banjo, along with his brother Verl on fiddle, decided to start their own group and played local square dances, fiddlers’ conventions, and the like. They farmed for a living and played music on the side over the next few years for a little extra income. Later, with the help of a cousin (Dennis Jenkins) on guitar and Howard Cole, also on guitar, they started the Jenkins String Band. The band must have been pretty tight, because, in 1934, they tried out for and got a job performing on the new radio station featuring hillbilly music (as it was then called), WBT’s Crazy Bam Dance in Charlotte, N.C.

The radio show fostered many up-and-coming acts that would later become famous—the Monroe Brothers, the Blue Sky Boys, Mainer’s Mountaineers, and the Morris Brothers. The Jenkins String Band worked there for two years, and. in 1936, Snuffy left to work with J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers when two-finger style banjoist Wade Mainer left the group. The band first went to work on WSPA in Spartanburg. S.C., for a short time, and, in 1937, they landed a job at WIS radio in Columbia, S.C., where Snuffy would stay and work with announcer Byron Parker and his WIS Hillbillies until 1948. After Parker’s death in ’48. the band renamed themselves the Hired Hands in his memory, as Parker was known as the “Old Hired Hand.” Snuffy would remain in Columbia, S.C., for the rest of his life.

My story begins with Snuffy Jenkins playing the three-finger style of banjo over the airwaves for the first time, beginning in 1934. Although the style wasn’t exactly new, it had been established for several years, and Snuffy had been playing it since 1927. But few people, outside of locals, had ever heard it before, and it caught a lot folks’ attention. One such fellow, driving through the Carolinas listening to his car radio, was Bill Monroe, who at the time was working with his brother Charlie as the Monroe Brothers. Monroe was later quoted as saying, “Snuffy Jenkins was the first man down in that country, and they were all listening to him, because he was on the radio, you see, and they weren’t.” Bill was known to keep up with different musicians—where they learned from, their abilities, and their locations—as he may have needed to call on them later. Bill and Charlie Monroe were there in 1936, working as the Monroe Brothers at WBT radio in Charlotte. N.C., the same station that Snuffy had been employed with since 1934. I believe the Monroes would have more than likely heard most of the local musicians in the area. Even Snuffy himself, who hardly took credit for anything throughout his life, claimed he thought he was the first man to play this style of banjo on the radio. If, in fact, Snuffy was the first to play this style over a radio broadcast, he would have been heard by nearly everyone in the immediate area, for radio was surely the main source of information and entertainment, other than the occasional live performance, which many couldn’t afford to go see. Nearly everyone had a radio and listened to it everyday for local news, weather, and some form of entertainment—just as we depend on television and the internet today.

It has been well documented many times that both Earl Scruggs and Don Reno heard Snuffy on the radio and also saw him at live performances along about this time, and both cite him as an influence. The point of this article is to explain why I believe Snuffy Jenkins was more than just an influence on the individual playing styles that both men and women would later develop on their own. I believe Snuffy Jenkins influenced what type of banjo Scruggs and Reno would eventually play throughout their careers.

There again, you have to realize the hardships of the times and consider just how tight money was in these rural areas. Like so many other farming communities in America, this part of the South hadn’t yet recovered from the Depression. There wasn’t such a thing as a credit card that, with the touch of a telephone, enabled you to have any number of different makes and models of great quality banjos at your disposal. Most amateur rural banjo players of the day played the cheaper open-back banjo that could easily be bought for just a few dollars. The majority of people could never even think of affording such a banjo as a Gibson Mastertone. All accounts, photos, and recollections of Smith Hammett and Rex Brooks show them playing a simple open-back banjo. As farmers, picking the banjo was solely a hobby or pastime. Although musicians were in demand and might make a few extra dollars a year playing square dances and fiddlers’ conventions, they mostly played at social gatherings or reunions. This is how Snuffy and Scruggs remember Hammett and Brooks playing at that time.

Snuffy was 16 years older than both Scruggs and Reno, who at the time were eight and ten years old, listening to him on the radio and seeing him live. They must have looked up to him just a little bit. Here was a man who had been playing the three- finger roll since 1927, performing on the two most-listened-to radio shows (with a sponsor) in the area since 1934, making a living at something other than farming. I have to believe they saw Snuffy Jenkins a little differently than, say, a relative who might visit on Sunday afternoons and play the banjo a little. I think Snuffy was seen by these two young boys as a professional musician, and it’s hard for me to imagine that they didn’t take notice of what kind of banjo he was playing—a big, loud, and shiny flathead five-string Gibson Mastertone! To a young boy who had never seen anything besides a plain old open-back banjo, the first sight of that big Gibson Mastertone with pearl inlay all over the neck must have been pretty awesome. And that sound—well, we all know that nothing else sounds like that!

With all that in mind, have you ever pondered the question, “Just why are the prewar Gibson flathead five-string banjos so sought after? Or, why are 99.9% of all bluegrass banjo pickers today, some unknowingly, playing some form of replica or copy of this same banjo, over seventy years after its introduction?” I would be willing to guess most bluegrass fans would answer, “Because that’s what Earl Scruggs played,” And they would surely be right. But have you ever taken it one step further and asked yourself, “I wonder just what or who influenced Earl and Don Reno to want a flathead five-string Gibson Mastertone in the first place?” There were many fine quality banjos available at the time. Paramount, Weyman, and Bacon & Day were some of the nicer quality banjos. Why did they both choose a 1930s model flathead Gibson Mastertone? They could have easily found one of the many two-piece flange archtop models that Gibson made. I believe everything has to have a seed planted, a foundation to get an idea started. Snuffy Jenkins, in my opinion, was that seed that compelled these young men to look for one of these fine banjos.

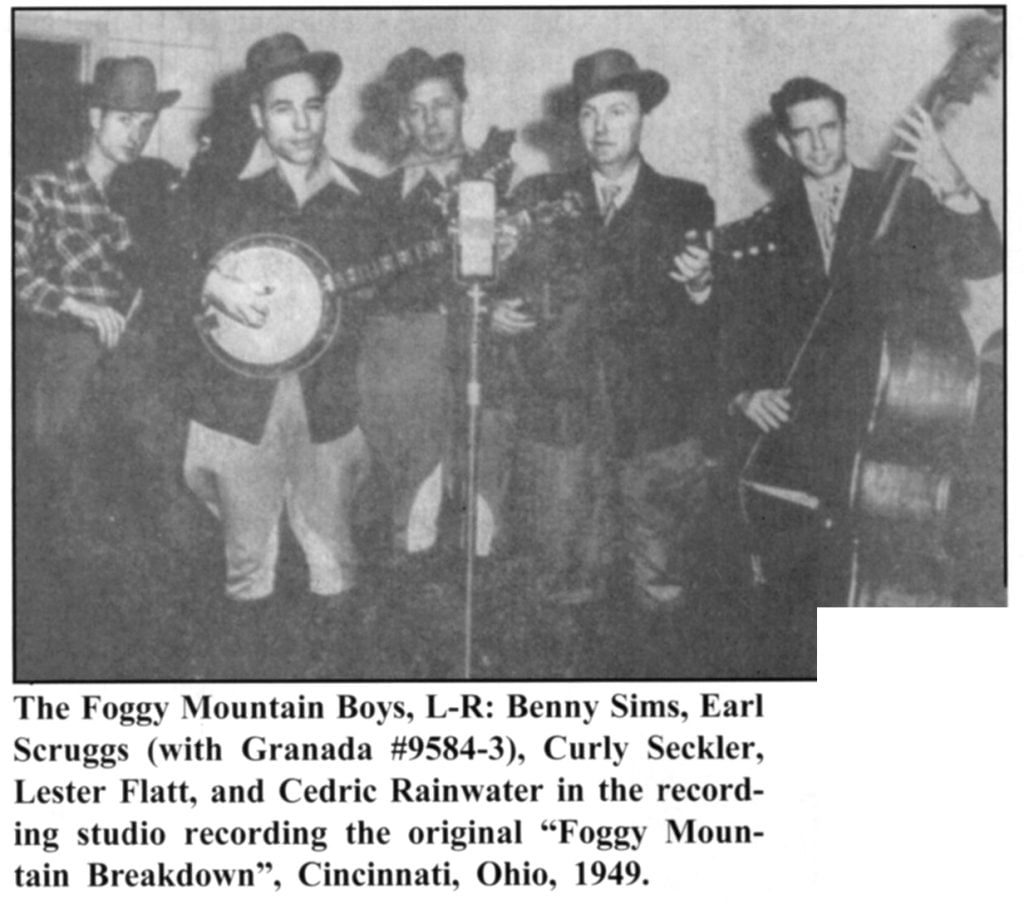

You may say, “Well, I’ve heard and read that these banjos were plentiful in pawnshops in those days, and maybe Scruggs and Reno just happened to find one, and that’s that.” Well, with all certainty and confidence, I can tell you that these banjos have never been plentiful. If you found one in those days, they were certainly less costly and not revered anywhere close to the extent they are today, but finding one would be very rare, as they were few and far between. To clarify, we’re talking about the 1930s-designed, one piece flange, original flathead. original five-string Gibson Mastertone, and that’s all—not any other type of prewar Gibson banjo, not even the now highly-prized original flathead tenor or plectrum banjos from that period, as no one was converting these to five-string at the time. In fact, out of the original flathead five-string Mastertones from this period that I’ve been fortunate enough to own, I have reliable accounts that Earl Scruggs and Don Reno had already seen, played, owned, or tried to buy nearly every one of them at some point within the last fifty years. The owners, even back in the 1940s and ’50s, were very proud of them, knowing that they had such a rare commodity. They would bring them out to where Earl and Don were playing a live show, just for them to play or take a look at. It’s a well-known fact that Earl Scruggs didn’t own an original five-string flathead Mastertone until after he’d already recorded several of Bill Monroe’s now-classic songs on Columbia records in 1946. He was in the most successful band of the day, more than likely making better money than any other five-string banjo player in the country. He was playing an RB-ll, a 1930s non-Mastertone model Gibson banjo with no tone ring. He finally found a flathead RB-75 around 1947 that he ended up trading to Don Reno for a Granada Sn. 9584-3 in 1948. There were very few of these banjos ever produced and they have always been hard to find—period. We’re discussing a very small number of fragile stringed instruments that would have been manufactured from 1930 up until the end of WWII, with a high estimation of somewhere around 250 produced. I don’t believe there are anywhere near that estimation still in existence. In the past twenty years, I’ve been able to locate only 93 of these rare banjos, searching all over the world. It’s nearly as likely for you to find an original Stradivarius violin unknown to the public than one of these banjos. So, Scruggs and Reno would have had to go looking specifically for one of these banjos back then. But why? I think it boils down to these young boys seeing a man playing this banjo, hearing the sound, and being influenced early in their lives. The man was Snuffy Jenkins. The banjos (there were two of them) were an RB-Granada Sn. 9584-3 and an RB-4 Sn. 9639-1.

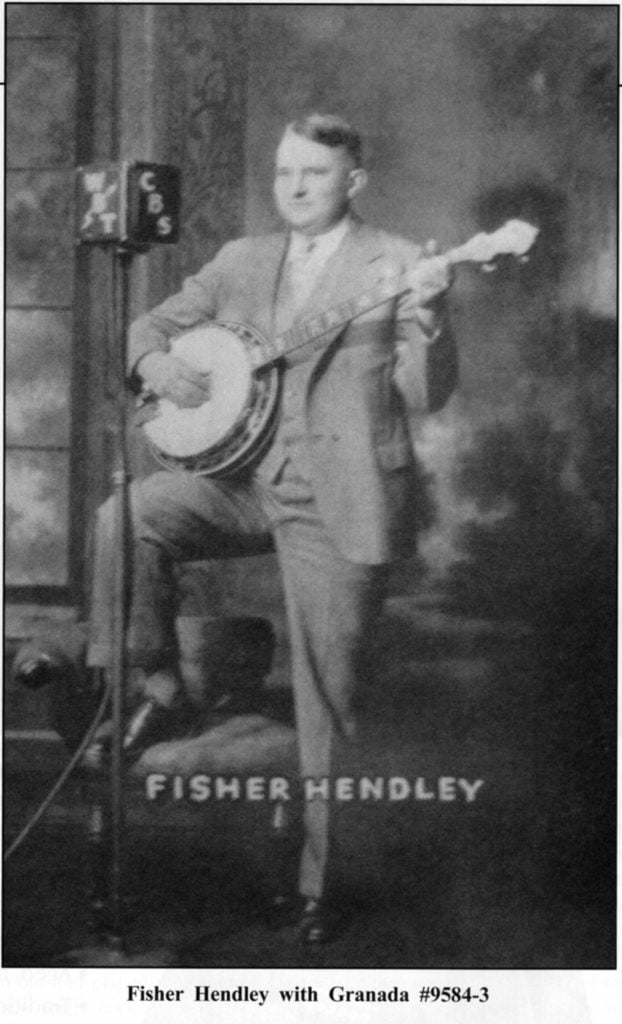

The banjos each have stories of their own that are quite interesting. I’ve just recently discovered the earliest known photos and history of one that I don’t believe had ever been recorded. I spoke with a man from Wadesboro, N.C., who is now 74 years old, and he revealed to me the earliest-known history of the RB- Granada Sn. 9584-3, no doubt the most famous Gibson banjo in the world. This is the banjo that Earl Scruggs would play and record with nearly his whole career. This is without a doubt the most photographed, recorded, and talked-about banjo. It has been altered quite a bit over the years, but it came from the factory an original flathead five-string Granada, gold-plated, engraved, with a hearts and flowers inlay pattern and beautiful curly maple neck and resonator. It’s played by a man who will go down in history as the greatest banjo player the world will ever know, Earl Scruggs, and rightly so. I’ve heard reports that Earl was offered more than a million dollars for this banjo several years ago. I’ve heard from reliable sources that a man named Fisher Hendley, a two-finger picker famous in his own right who had a band on WBT in Charlotte in the mid- 1930s. purchased this banjo new in 1934.

I also know that Snuffy Jenkins bought this banjo from Mr. Hendley a few years later, while they were both working on the WBT Crazy Bam Dance in Charlotte. I’d always wondered about these stories and if they were true, having happened so long ago.

Recently, while tracking down another original flathead five-string RB- Granada, I happened upon an older gentleman whose father’s name was Dewitt Wheless. I couldn’t believe it, another Dewitt? Mr. Wheless also had his own band on the Barn Dance at this same time in the 1930s. It turns out that Dewitt Wheless was a good friend of Fisher Hendley. One fine day in 1934, they both decided to order one of Gibson’s new gold-plated Mastertone banjos and proceeded to their local Gibson dealer in Wadesboro, N.C. It was owned by a fellow named Jim Graves, who also ran the local barbershop in town. At this time in the rural south, there were very few true music stores. It was quite common for jewelry stores, furniture stores, and, yes, even barbershops to have a Gibson dealership. The Gibson company was expanding its enterprises and would give a dealership to pretty much any kind of bonafide business. Mr. Hendley and Mr. Wheless walked into the barbershop together, and each man ordered his own original five-string flathead Granada. Several months later, in 1934, they picked them up together, according to Wheless’ son (who is now 74 years young). Even though he was only four years old at the time, he remembered very well such accounts told by his father many times in later years. I spoke with him for about 45 minutes and found all he told me to be perfectly in line with everything I’d ever heard concerning both of these banjos. This is the earliest known history of Earl’s Granada, since the time it left the factory.

The other Granada turns out to be an exact mate to Earl’s—another standard RB-Granada with hearts and flowers inlay, which came off the line right beside Earl’s and has belonged to a friend of mine since 1965. Snuffy Jenkins bought the RB-Granada Sn. 9584-3 from Fisher Hendley around 1936. I have existing photos of Snuffy playing the banjo around this time. He played and recorded with this banjo until 1940, when his brother Verl located another banjo, RB-4 Sn. 9639-1, in a Spartanburg, S.C., pawnshop for $40. Snuffy reportedly told his brother, “I don’t need another banjo, I already have a good one.” What an understatement! After seeing the RB-4 and thinking it over. Snuffy decided that $40 was a pretty good price and bought it. Snuffy said many times later, “I stole it. I thought it was a $65 banjo when I bought it!”

The earliest known history on RB-4 Sn. 9639-1 is that it was bought brand new for $175 in 1935 from Alexander Music House in Spartanburg, S.C. The first owner’s name is not known. Apparently, he bought the banjo new, kept it for a few years, got married, got into debt, and had to pawn it for $25. This is the story quoted by the Spartanburg, S.C., pawnshop owner one day in 1940, when Snuffy Jenkins walked into his shop and inquired about the banjo. Snuffy played and recorded with it for the rest of his life. The banjo remained in the Jenkins family for 64 years and had never been on the market or offered for sale until Toby Jenkins, Snuffy’s only child, decided to sell it to me on May 5th, 2004. It has survived in 100% original condition, a truly rare thing, as most of these banjos have been altered in some way over a period of sixty years or more. It’s more than likely due to the fact that it’s only had two owners in 69 years. The RB-4 Sn. 9639-1 features a wonderful-size, very playable neck—a big reason why, I believe, Snuffy chose it over the Granada. It’s well known that Earl Scruggs, in the 1950s, cut the original neck down on the Granada with a wood rasp, indicating it had a pretty big neck. The banjo also features a flying eagle inlay pattern, an uncut label, standard chrome plating, clamshell tailpiece, original factory headguard, and a twenty-hole flathead tone ring. It’s so original, it’s never even had fifth string spikes installed and still retains its original friction fifth peg and nut. Snuffy never used a capo and would just tune up when necessary.

After purchasing his nearly new banjo, Snuffy proceeded home to Columbia, S.C., where upon comparing what would become two of the most famous Gibson banjos in the world, he found the RB-4 suited him better. He then sold the Granada for $90 to a 15-year-old boy from Buffalo, S.C., who had been following him around for a few years. The boy’s name was Donald Reno and the year was 1940. Don kept and played the banjo for a few years, went into the service in 1943, and left the banjo at home. He mistakenly left a cake of fiddle rosin inside the case and, after returning home a few years later, found it had melted all over the pot of the Granada, ruining much of the original gold plating and wood finish. Don continued to play the banjo for a few more years. By this time, it had really started showing signs of wear and tear.

In 1948, he and Earl Scruggs made the now-legendary trade at WCYB radio in Bristol, Va./Tenn. Don claims that Earl had mentioned several times liking the sound of the Granada and wanted to make a trade with him. Don also stated that Earl didn’t have a suitable banjo, at first, to trade for the Granada until he bought the RB-75 from Hayes Hall in 1946 or ’47. Earl had recorded several songs with Bill Monroe on this banjo a year or so before, and Don said it was as clean as a new one. They made the trade, with Don throwing in a Martin guitar because the Granada was so worn. Ralph Stanley told me he was standing there in the studio when the trade went down and relayed the story to me. Earl continues to play and record with the Granada today.

I find it incredibly ironic that of the three men, who are credited with furthering the five-string banjo probably more than anyone and also pioneering the three-finger style, all three owned and played this same Gibson Granada Sn. 9584-3. Snuffy Jenkins never sought any recognition while he was alive, and I hope I’ve shined a light, though posthumously, on a few of the contributions that he unknowingly gave.

I hope this tribute sums up the effect, I believe, Snuffy Jenkins had on Earl Scruggs, Don Reno, and generations of bluegrass banjo players the world over— just by playing these two banjos. It also explains partly why we look at original prewar Gibson Mastertone flathead five-string banjos the way we do today—as the finest banjos the world has ever known. Thanks Snuffy!

Jim Mills is a Sugar Hill Records recording artist, a four-time IBMA Banjo Player Of The Year, and a current member of Ricky Skaggs’ hand, Kentucky Thunder.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I need help identifying my dads old master tone. I think it’s a rb6

Hey!! I have a Gibson master tone pre-war 5 string banjo! I liked your article it was great! Now I need to know if you can help me point me towards someone I can trust to appraise my banjo and fix the fifth string TP is loose