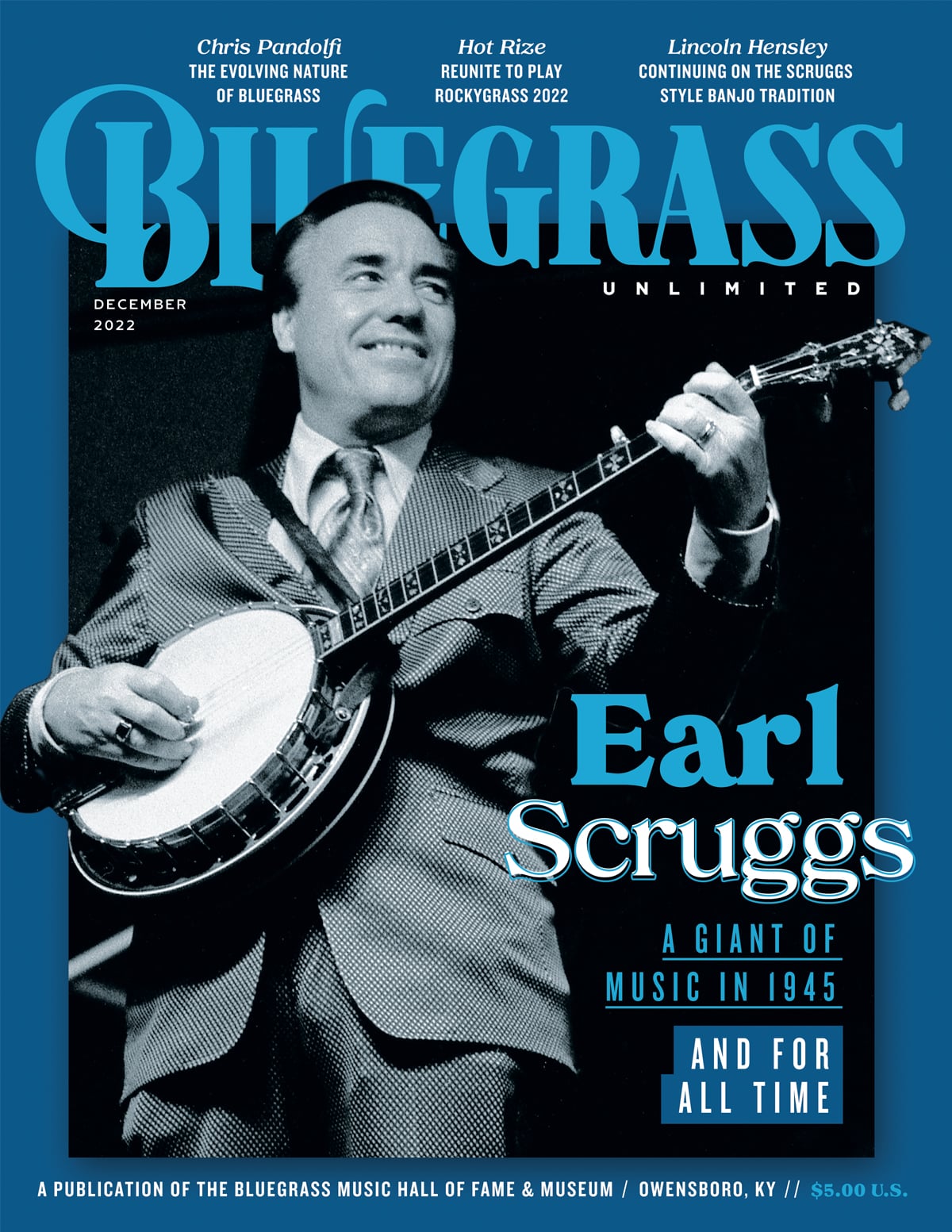

Home > Articles > The Archives > The Fiddle Music of Art Galbraith: An Ozark Family Legacy Passed Down Four Generations

The Fiddle Music of Art Galbraith: An Ozark Family Legacy Passed Down Four Generations

Photos by Virginia Curtiss

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1984, Volume 18, Number 7

Seventy-four-year-old Arthur Galbraith, of Springfield, Missouri, accurately represents the essence of old-time fiddle music popular in the Ozarks over 100 years ago. Art plays many of the same tunes that his Uncle Tobe Galbraith did, in the same lilting, traditional style that has been passed down in his family four generations.

Andrew Galbraith, Art’s greatgrandfather and a 16-year-old volunteer in the War of 1812, returned home to Hawkins County near Rogersville, Tennessee at the end of the war. He was a dancing master and a fiddler. In 1850 he moved his family to a farm on the banks of the James River in southwest Missouri. Friends had written to him, saying, “Come to Missouri. Here’s the kind of land we want, the kind of river we like, the kind of springs we like.”

Art thinks his grandfather, Stephen Galbraith, would have been a better fiddler if he hadn’t been so interested in populist politics. In the 1870s Stephen worked in the United States Land Office in Springfield, Missouri, and was a “protest politician,” Art says. He still has many letters from his grandfather’s correspondence with government figures about issues of the time.

Tobe Galbraith, born in 1853, played with the same light touch on fiddle as Art does now. He had a house in the northeast corner of Springfield with a 20 x 40 foot living room big enough for three sets of square dancers. “He held his fiddle low on his chest,” Art reminisces, “and he’d just sit there. He was tall, long-armed, long-legged; he sat and played by the hour, just as smooth and glib and pretty as you can imagine.” Tobe had three sons and one daughter who all played music too, so they often hosted music parties and dances. Art says his family was very much slanted toward the Confederate cause during the War Between the States and afterwards. Tobe “remained unreconstructed enough that he would not play ‘Marching Through Georgia,’ ” Art remembers, “and he left the room when someone else played it.” While still a boy, Art recalls “a picture of Robert E. Lee hanging in our dining room next to Woodrow Wilson.” Missouri was a border state; neighbors and families were divided. “In the family cemetery on my farm is buried one of my two great-uncles who were both Civil War soldiers,” Art adds, “one on one side and one on the other. They fought opposite each other in the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas, and neither knew that the other was there until later.”

Born in 1909, Art grew up “fishing, swimming, and wading in the James River” and listening to a lot of music. He started fiddling about the age of ten on an instrument his father bought from Tobe’s son, Clay. Clay played a “rough fiddle —extremely loud,” Art smiles. “Nobody ever drowned him out.” A soldier in the Army of Occupation after World War I, he and other members of his platoon lived with German families as a part of reparations. Clay’s host family had lots of parties, music, singing, and daughters. Art says. “There was a crowd there all the time.” When he got his orders to sail from one of the French ports, the “old man” sold his German fiddle to him for what amounted in marks to $4.85. “You played it, and you should have it,” he insisted. On his way home, Art continues, “a lot of his buddies knew that he played, and they worried him to death to play all the time. Well, he got awfully tired from it; fact of the matter, he almost didn’t get any rest because of it. So one day he just walked out to the rail and threw the bow as far as he could out into the water, and said, ‘Now maybe I’ll have some rest.’ ”

Clay taught Art his first song on fiddle. “He showed me one finger at a time, ‘My Old Kentucky Home,’ ” Art states, “and ‘Little Brown Jug’ was the next one.” Art’s cousin, Clay, as well as another uncle, Mark Galbraith, were both very patient and encouraging when he was learning to play. As a result of an accident with a corn cob and a hatchet when he was young, Mark only had three fingers, “but he could play a lot of tunes with those three fingers,” Art affirms. “He taught me lots of tunes.” Around this time Art remembers, “My Dad would embarrass me by wanting me to play for people when they came to see us. I was just learning to play, and it sounded horrible … But in retrospect it was good for me because it made me try harder.” When he was young, Art says his “finest joy” was “a visit to Uncle Tobe’s.” Art “used to go out there in the day time, and the other boys would be there, and Tobe would be making garden or something like that. I’d say, ‘How about playing me some fiddle tunes?’ ” Years later Art believes, “My music now is patterned more after him than anybody else, although I never sat down with him in my life, with two fiddles and tried to copy him. I sat and listened to him a lot, and he’d play for me any time I’d ask him. I picked up a lot of things that have stuck in my memory I didn’t know were going to. Later on when I got to playing a little better, I found out that I recalled his tunes very well.”

During the ’30s Art got a mail order tenor banjo from Sears Roebuck; he learned to play it, as well as mandolin. “It was quite the thing,” he smiles. “I played for lots of dances, rhythm for a fiddler. Now I wish I’d never even messed with the banjo because it took time away from my fiddle. I’d know a lot more old, old tunes now if I’d concentrated on it then. But oh, I had to have a banjo…”

With the determined assistance of his family and the small salary from a job as the editor of the college annual in 1934, Art was able to graduate from Southwest Missouri State Teachers College (now SMSU) in Springfield. Art and his furture wife, Margaret, both wrote for the Southwest Standard newspaper. He taught school for four years, first in the one-room country school he and his father had attended, (grades 1-8), and later at Nichols School, eventually a Willard, Missouri outpost school and now abandoned (grades 7-8 and principal). The next year Art took one month’s training at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri, and taught adult education at a W.P.A. night school. Class topics included English, French, public speaking, and gardening. Civil Service examinations came up for positions at the post office around this time, so Art took the test and applied for a job as a clerk. Employees from the post office were pulled out to administer the new Social Security program and to distribute World War I bonuses, and Art was soon called in to start his 31-year career. With one year at the post office behind him, Art and Margaret were married in 1937. They lived in his family’s remodeled farm house for the first couple of years, kept livestock, and operated the farm with a number of different tenants. He remembers 4:00 a.m. shifts and Christmas rushes with 16-hour days from December 10-27 and no overtime pay. After renting for one and a half years in Springfield, they bought the house and land on New Avenue they live in now and moved in on Armistice Day, 1940. The Galbraiths have two sons, Mark and Tom. Mark played violin in school orchestras, and Tom “went nuts about music early on,” Art says. In the late ’50s/early ’60s he was in a rock and roll group called the Blue Notes. He learned to play both banjo and guitar well, and together with Dudley Murphy, started the Bluegrass Society of the Ozarks, based in Springfield.

In the 1950s Art says there was a “new craze of square dancing around Springfield. A band Art formed played quite a bit for the late Rex Kreider, a locally successful farmer, horseman, and dog raiser. “He was a perfect wizard about teaching square dancing, Art comments. “He could get fifteen sets of people dancing in fifteen minutes! They played for Rex, who later on was the last person in the area to want live music or dances, at the YWCA, Drury College Walker Dance Studio, the Elks club, and anywhere “there was enough floor to get a lot of people out.”

In 1951 Art won a fiddlers’ contest at Pythian Castle Lodge in Springfield. First prize was a trip to the National Folk Festival in St. Louis, Missouri as a participant. Sponsored by the Globe Democrat, it was a huge event at Kiel auditorium with an audience of several thousand people, dancers from Cuba, and Indians from the west. From this point on, Art began to get more national attention in folk circles. In 1954 he returned to the festival with Kreider’s dancers. They had “the prettiest square dancing formation that I’ve ever seen… all in fancy skirts and costumes,” Art recalls. They moved “like clockwork. It was absolutely fantastic.”

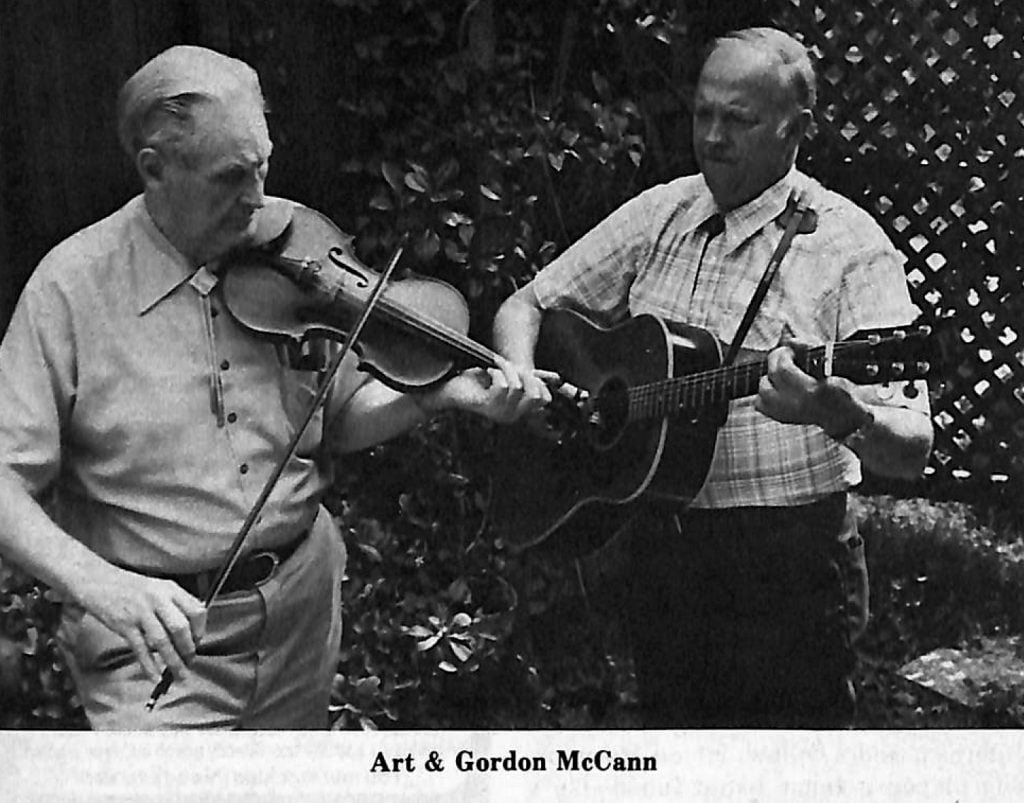

From the ’50s through the ’70s Galbraith and a fellow named Herndon, who played a tenor banjo tuned like a guitar, went down to Ozark, Missouri nearly every Saturday night to play at the late Emmanuel Wood’s open jam on the town square. It was “held in an old store building which was very old and rickety,” Art notes. “But the acoustics were good, and I met and played with many musicians —some who were good and some who were not so good. It was always lots of fun.” Art met Gordon McCann, his favorite guitarist, at Ozark. “I am more pleased with Gordon than with any accompanist I ever had,” Art states. “We seem to blend better and to rehearse better together than anyone I have ever played with.” McCann, a dedicated historian and folklore researcher of the area, had a close association with the late Vance Randolph, renowned Ozarks folklore writer. Gordon is presently completing Randolph’s Supplement to Ozarks Bibliography, a monumental reference volume including a collection of over 1400 reviews of books dealing with different aspects of Ozarks folklore. Art adds, “There’s a whole lot of rhythm guitarists that just never get out of these chords. But Gordon likes the use of a lot of minors, and I do too, especially in waltzes. If you listen to the records carefully, you’ll find out there’s more guitar there than you usually hear.” From 1972-74 Art picked with the Fiddlers Four, a group of friends from the Ozark get-together at Silver Dollar City, an 1880s theme park near Branson, Missouri. Herndon, on tenor banjo, Emmanuel Wood, on guitar, Byron Kelly, a black bass player, and Art, on fiddle, played weekends at the spring Root Digging Days and the fall craft festival. Galbraith got good exposure both there and at the Frontier Folk Life Festival near the Arch in St. Louis where he has performed at the past five years. He calls the latter “one of the most enjoyable things we’ve ever done. We’ve just gotten to where we’re kind of a fixture of it and love to go.” From this festival, Art has made booking connections with the Missouri Council of the Arts and many other varied groups. He played the 41st National Folk Festival at Wolf Trap Farm Park in Vienna, Virginia in 1979, where a Rounder scout heard and approached him about his first album, “Dixie Blossoms.” The record was taped in 79 and ’80 at the studio of The Ozark Folk Center in Mountain View, Arkansas, a place Art and Gordon play frequently, by engineer, Aubrey Richardson. It was produced by Charles Wolfe, an English professor and folklorist at Middle Tennessee University. Following good sales and several excellent reviews, Mark Wilson, a professor at San Diego University and producer for Rounder, called and asked Art if he would record another album after a festival in San Diego where he was booked. The record, named “Simple Pleasures,” also for Rounder came out in October, 1982. Art and Gordon can also be heard on the latest album by cowboy singer, Glenn Ohrlin, from Mountain View, Arkansas, which they taped in California while doing the second Rounder project. Art plays “Beaumont Rag” on “Down By The Rio Grande,” an album of western music recorded live at the Frontier Folk Life Festival from 1977-79. Art has an idea for a third record of all waltzes which he hopes will materialize soon.

Busier now than they ever have been, recent activities for Art and Gordon include a nine-city tour through Missouri, Kansas, and Arkansas during the spring of 1982, judging several area fiddling contests, the annual folk festival at Eureka Springs, Arkansas, and the past three years at the General All-State Meeting of the Oklahoma Fiddlers Association. “We go there and we just jam ’til the world looks level,” Galbraith smiles.

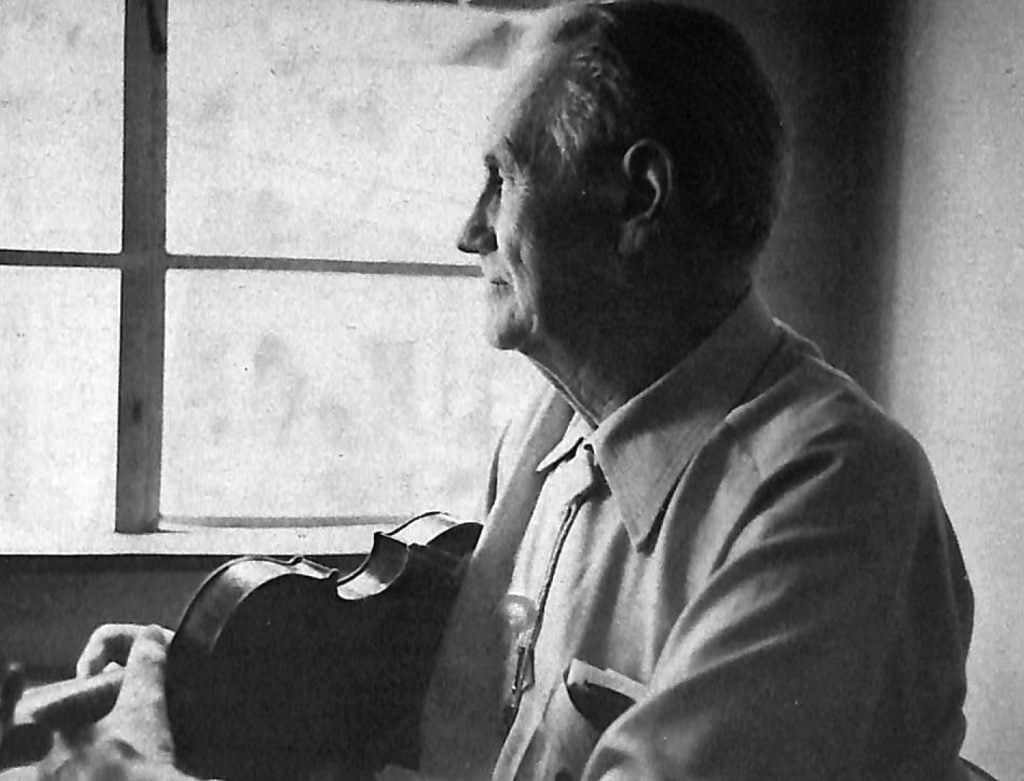

Vance Randolph said many times, “Art Galbraith is the best Ozarks fiddler I have ever heard.” Charles Wolfe describes Art’s music as “a delicate, stately lilting style that has seldom been commercially recorded.” He adds, “It has a special beauty that suggests why the old timers in southern Missouri still call it ‘violin’ music.” Art says simply, “I do play like Uncle Tobe did.” He continues, “I play a rather smooth fiddle, but I can’t compete with a bluegrass bunch. I don’t play as loudly, for one thing, and as a general rule I don’t play fast. I used to play fast for dances, but I don’t like to. It kind of spoils the music for me.” He remarks with a slight smile that often one will “get hold of a fiddle with a bluegrass bunch, and it’s just whip the horses…really an athletic event rather than a musical one.”

Although Art has definitely developed a style of his own, he listens to albums and tapes of many other fiddlers. He likes Kenny Baker’s style and plays several of his tunes, and he admires some Texas and Oklahoma fiddlers. On the subject of labels, Art notes, “I’ve been to a lot of these festivals, and they often introduce me as playing Missouri fiddling. I wouldn’t absolutely call it that. There was a lot of Missouri fiddlers up north of the river… and in the central part of the state that play awfully good fiddling. But not any of them is consistent with the others. I think that’s the beauty of fiddling; you let ten fiddlers play the same tune and every one of them will have a different stamp on it. It wouldn’t be at all interesting if everybody sounded alike.”

As mentioned before, much of Art’s material consists of memories of his Uncle Tobe’s pieces. He also composes pieces himself that are “almost traditional. They’re of the same vein,” he says. “Fiddlers get in the habit of playing a certain type of tunes, and they play them over and over. And too often, I think, they play the same tunes their neighbor plays, and somebody else plays. I do like to play a different tune.” One of the “different tunes” is “Rocky Mountain Hornpipe,” learned from his uncles, Tobe and Mark. “They both said it was one of the oldest pieces they knew and could trace it back to the 1820s,” Art says. “If you use your imagination a bit, it has sort of an Indian beat to it. My mother used to sit and pat both feet to it and said, ‘I always think I’m seeing an Indian dance.’ ” Art’s “all-time favorite tune” is “Flowers of Edinburgh.” Tobe said, “That’s the oldest tune I know, because I know my father played it, and I know he learned it from his father. While at Wolf Trap, Art discovered that his version of this song was very similar to the way the Irish fiddlers there played it. “McCraw’s Ford,” according to legend, was a song that country Dr. Brown dreamed one night when he fell asleep in his buggy crossing the ford, and “Over the River to Charley’s,” a parody of a 1748 Jacobite song, “refers genially to that love of ale and wine which Prince Charles displayed as early as the age of fourteen,” comments Andrew Long.

Art is an instrument collector; he has around 18 fiddles, some Gibson mandolins and guitars, and a couple of Martin guitars. His favorite fiddle is a Stradivarius copy called a Conservatory Strad, dating some time between 1910 and 1930. As far as technique, he uses very little rosin and usually plays with the upper two-thirds of his bow. “I’m not a stickler for having this classical stance,” Art says, “but I do like to have it up to my chin. It’s not necessary to hold it too tight.” In recent years Art has done some instrument repair and restoration, particularly on violins, and he re-hairs bows. It’s an enjoyable hobby for him and a good way to meet other fiddlers. Art has also done some free-lance writing for The Ozarks Mountaineer, a folklore magazine based in Branson, Missouri.

Art is pleased with the younger generation of pickers coming along that is interested in traditional music like his, and he is optimistic about its preservation. But he notes a continual change; “It’s immigrant music by immigrants. It came from the British Isles through the Carolinas and Tennessee and Kentucky…through here by immigration, I always say, well, the immigrants have changed, and I believe the immigration music will change.”

At the age of 74, Galbraith says he can play much better than he could 25 years ago, and he learns new tunes more quickly and easily. Physically, mentally, and spiritually going strong, he adds, “My music in my humble way is a great satisfaction to me. It has a way of easing my mind when I am disturbed, and is an ever present means of bringing order to me when I need it most. In my many contacts with people, I find that music is the greatest thing to bring a sense of pleasure to others as well.” What better accomplishment than to realize that through a life of music you have made yourself and others a little happier?