Home > Articles > The Tradition > When Strings Become Bridges

When Strings Become Bridges

For over half a century, old-time/bluegrass music has connected the author with a wide variety of interesting and highly talented people, including autoworkers in Flint, Michigan, musicians in New Zealand, and Virginians transplanted to Detroit. The following is a selective appreciation.

On the Fourth of July weekend in 1971, I attended Carlton Haney’s bluegrass festival at Watermelon Park in Berryville, Virginia. There was a band present whose leader announced the Bill Clifton song “Where the Willow Gently Sways”—the lyrics refer to the Shenandoah River—and he remarked that he never dreamed that he’d actually be performing that song by the banks of the Shenandoah.

Fast forward to 1989. I had a visiting appointment at the University of Waikato in Hamilton, New Zealand, and when I picked up the local newspaper shortly after my arrival, I was captivated by an entire page devoted to the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band. I immediately recognized that this was the group I had seen 18 years earlier in Berryville. The article named the band members, so I telephoned Paul Trenwith, the banjo player (this was in the days of landlines and paper telephone directories). As soon as I explained the reason for my call, Paul invited me to an impromptu jam session at his house. I didn’t have an instrument with me, but there were extras available, and I was handed a guitar. At the end of the evening, one of the musicians told me that he was forming a new bluegrass band, and invited me to join. Of course, I accepted, and I played with the Mystery Creek Bluegrass Company for the duration of my six month New Zealand stay. One of my colleagues at the university kindly lent me a Martin Sigma guitar that he wasn’t using, so I had an instrument readily available for practice and performance.

I was surprised to discover a number of highly accomplished bluegrass musicians in New Zealand (some 9,000 miles from Virginia). After all, one doesn’t find Maori music being played in many American cities. But, in retrospect, I shouldn’t have been so surprised. At the Berryville festival, in addition to the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, the Japanese band Bluegrass 45 was on the bill, and the “Personal Appearance Calendar” in Bluegrass Unlimited routinely included overseas venues. In fact, the June, 1971 issue of BU contained an article by Mike Seeger on the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band! Bluegrass music had become an international phenomenon.

My introduction to bluegrass took place in the spring of 1966. I had moved to Durham, North Carolina to begin graduate school, and one of my new friends took me to the Union Grove Fiddlers’ Convention for a day. As we walked toward the schoolhouse grounds, I could hear the strains of a couple of instruments; it was a session with Roger Sprung on banjo, and probably Dorothy Rourk on fiddle. I was mesmerized. In addition to the splendid schoolyard jams, there were some amazing bands involved in the formal competition. By the time we headed home, my head felt as though it contained a continuous tape recording of the day’s performances. My ’47 Martin D-18, which had previously served my interest in folk music, was immediately pressed into attempts at flatpicking.

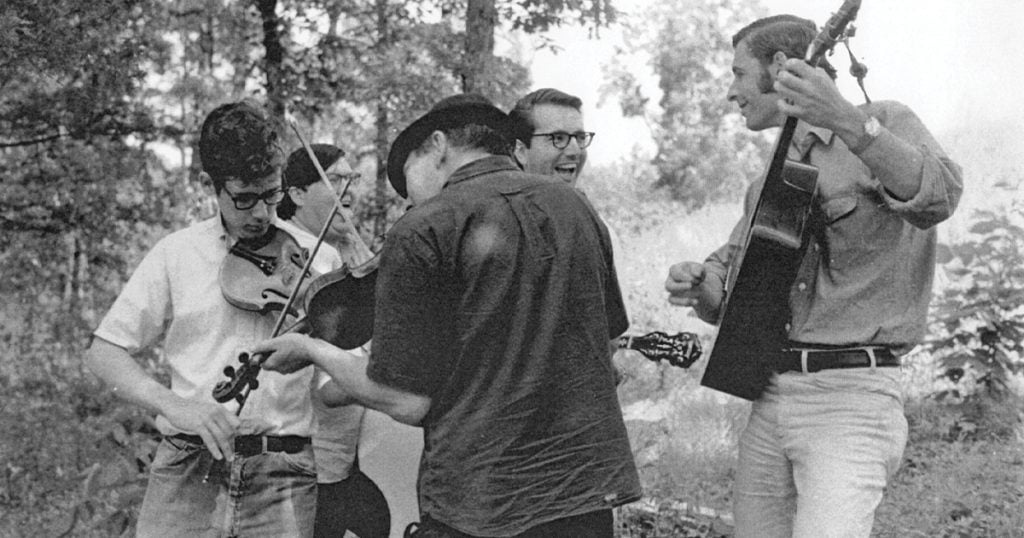

In 1969, I moved to the Charlotte area, where I took a one-year academic job at the local branch of the University of North Carolina. By that point, I felt ready to reach out to other musicians, so I posted a note on several university bulletin boards: “Bluegrass Musicians Wanted.” Within a few days, Mark Wingate, a student, knocked on my office door. Mark was a remarkably talented multi-instrumentalist, way above my level, but the two of us hit it off, and soon thereafter he invited me to a jam session at the home of Clyde Williams, an old-time fiddler who lived outside of town in an area known as Mole Hill. Also present was Jim Scancarelli, whose accomplishments on banjo, fiddle, photography, and the Gasoline Alley comic strip will be familiar to readers of this magazine. Clyde, then age 47, had learned many of his tunes by listening to the Grand Ole Opry on his living room radio, favoring the Gully Jumpers, the Skillet Lickers, and—most of all—the Possum Hunters.

Clyde told us that he paid close attention to the Opry fiddle tunes, and when a song came on the air, he would turn down the volume and practice the tunes he had just heard. That unorthodox learning method clearly paid off. Thanks mainly to Clyde’s prowess, our newly formed band, The Mole Hill Highlanders, was the second runner-up old-time band at the Union Grove Fiddlers’ Convention in 1970. The following year, Clyde won first prize in the old-time fiddle category.

Although the university was located in Charlotte, I lived outside of town on Poplar Tent Church Road, just a few miles, it turned out, from the legendary J. E. Mainer. One day several of the Mole Hill Highlanders paid a visit to J. E., who entertained us with stories, including one about discovering a Stainer fiddle lying in pieces by the railroad tracks near his house. He gathered up the parts, glued them back together, and ended up with a fine instrument.

At that time, the Mole Hill Highlanders hosted a weekly 30-minute radio show from WFMX in Statesville; we told J. E. about it, and he promised to tune in. The station management wanted proof of our popularity, so we implored our radio audience to send in cards and letters. Within a few days, we received a dozen or more testimonials which, upon close examination, were all revealed to have been written by J. E. Mainer!

I had been playing guitar with the Mole Hill Highlanders, but having listened to a lot of bluegrass, I was also yearning to play the banjo. Fortunately, I was introduced to C. E. Ward, an exceptional Charlotte luthier, who had recently converted an old Gibson raised-head tenor banjo to a beautiful 5-string. At the time I couldn’t pick the banjo at all, but I happily paid C. E. $250 for that instrument, which I still am proud to own. I immediately purchased Earl Scruggs’ instruction book and every day, from that point on, I faced a struggle between writing a dissertation and learning a new banjo lick. And for a long time, the banjo always won.

So, it took me several years to finish my degree, and re-enter the academic job marketplace. I ended up teaching in Flint, Michigan, which in 1972 was a highly prosperous community, due principally to the success of General Motors (in an extreme reversal of fortune, it is now near the nation’s top in per capita poverty). I knew that many people had moved to Flint from the South in order to work in the local factories, and I suspected that there would be some bluegrass pickers among them. But that subculture, if it existed, was never advertised.

As luck would have it, many students at my university also held jobs in the automobile factories. Accordingly, at the beginning of each semester, I mentioned to my classes that I was looking for bluegrass musicians, and I invited them to provide any contact information that they might possess. One day a student handed me an index card with a phone number on it. I could hardly wait for evening to arrive, and after dialing the number, I found myself talking to Mack Allred, who had moved to Flint from Alabama years earlier to work for “Generous Motors.” I soon joined him and a few other pickers at a house in Flint, and after nervously playing “Dear Old Dixie” and “Devil’s Dream” on the banjo, with Mack’s rock-solid rhythm guitar backup, I was welcomed into the fraternity. With Mack and several others, we formed a band called the Dixie Hoedowners (I was the only Yankee in the group). It was many months before Mack asked me what I did for a living, and by that time he was calling me his “son,” so discovering that I was a “professor” amused him greatly.

During my days in Flint, I still maintained occasional contact with Clyde Williams. Clyde had long been obsessed with the sound of the Grand Ole Opry “horn” that George D. Hay, the “Solemn Old Judge,” blew at the beginning of each show back in the 1940s, and he had attempted many times to reproduce it without ever feeling that he had gotten it quite right. One day a UPS truck pulled up in front of my house to deliver a thickly-wrapped package. Inside was a hand-fabricated wooden object, about 18 inches long, with a slot on the top and a mouthpiece at one end. It had a mustard-yellow finish, and on the back was an inscription: “Built by Clyde L. Williams for Chuck Dunlop.”

Naturally, I assumed that this was Clyde’s latest re-creation of the Opry horn, but I had no way of knowing whether he had succeeded in replicating the original sound. A short time later, however, I began hosting a Saturday night bluegrass radio show on the local NPR station, WFBE. It ran for two hours, and I was given a free hand to play tracks from my vinyl record collection, and provide whatever commentary came to mind. During one show I decided to present Clyde’s device, which I announced as “the mystery sound”. I blew it over the studio microphone, and invited listeners to guess what it was. Predictably, some callers identified it as a Coke bottle, and others as a jug. But, just as the show was concluding, a woman called in.

With a distinctively Southern drawl, she confidently proclaimed, “I do believe that’s the horn that the Solemn Old Judge used to blow on the Grand Ole Opry.” At that moment, it was clear that Clyde’s efforts had been validated, and when I telephoned him with the news, he was overjoyed.

In more recent decades, I have played in several bluegrass bands in the Ann Arbor area. One of them included a banjo player from Germany whom I met through the Banjo Hangout. Another included Bob Campbell, an accomplished fiddler, whose son Jimmy was a Blue Grass Boy from 1990-93, and whose grandson Casey is an emerging Nashville star. Through Bob, I met Steve Harper, who by his late twenties had absorbed Bill Monroe’s entire repertoire, and he had the mandolin chops and voice to go with it. Steve brought in Don Ford, a fine singer, and later, Mitch Manns, an exceptional musician and big-hearted guy, who had toured nationally with country bands, and had played at one time with Jimmy Martin. Marty Somberg joined us on fiddle, and Adam Cogan on bass.

Honoring our love of the music created by the Father of Bluegrass, we named our band “Southern Flavor,” and our bookings in southeast Michigan included the Wayne County Coon Hunters’ Club, the Kentuckians of Michigan, and the Huron Valley Eagles Club—all memorable venues not typically visited by philosophy professors.

Bluegrass bands often have relatively short lifespans, and within a few years I found myself once again looking for like-minded pickers. I frequently consulted Craigslist, but on that website the term “bluegrass” can refer to anything from folk music to rock ‘n’ roll. Eventually, however, I came across an authentic-looking post by Ken Edwards. Ken turned out to be an excellent fiddler from Virginia. For a brief period, we joined up with some young guys who favored a progressive style, but after that band folded, Ken introduced me to two fellow Virginians who got together regularly on Friday nights in the Detroit area to socialize and play music, much of it from the Stanley Brothers’ catalog. That was little wonder, since Ken, “Pee Wee” Barton, and “Mousie” Hall all grew up within shouting distance of the Stanleys, although they didn’t actually discover each other until they lived in Michigan.

Mousie, now 97 years old, and a veteran of the Battle of the Bulge, (he carries a card in his wallet to prove it) told me that he was once offered a job with the Stanley Brothers, but turned it down because he didn’t want to travel. Pee Wee, a retired contractor, is an exceptionally talented and fearless craftsman who has reset necks on vintage Martin guitars, and rescued numerous fiddles from garage sales. When Pee Wee was a young boy, the Stanley Brothers often performed at his school, and he recalls that Carter always referred to their music as “old time country” (never “bluegrass”).

In all my times getting together with these three, there has seemed to be an unspoken understanding that we wouldn’t venture into conversational topics that might undermine the camaraderie that our musical commonalities have fostered, a decision that has surely allowed those relationships to flourish. Nobody in the Detroit ensemble knows anything about my religious preferences or political views, and nobody cares.

I’ll never rise to the level of musical excellence attained by some of the phenomenal people I’ve had the privilege of pickin’ with over five decades, but the acceptance and friendships I have found through bluegrass music have added a dimension to my life that I couldn’t have found any other way. Bluegrass folks tend to be exceptionally warm and generous, and the world could use a lot more like them.

I am grateful to all of the people mentioned in this article, and also to Fred Bartenstein, Burton Lindsey, Ted Morris, and Colleen Trenwith.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I have magazines dating back to 2006. My husband passed away and I no longer subscribe to the magazine. Any one interested in them?