Home > Articles > The Archives > Vern Williams—“You’ve Got To Let It All Pour Out”

Vern Williams—“You’ve Got To Let It All Pour Out”

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1986, Volume 20, Number 12

When you’re talking about traditional bluegrass music on the West Coast these days, chances are that you’re talking about the Vern Williams Band. Although there are other, solid, bluegrass bands to be found throughout the western states, it is Vern Williams that has managed to put together a group that can hold its own with any traditional band currently active, east or west. By just about any standard this is an exciting, no-nonsense, Monroe-style group of the first order, who have managed to effectively mix the important traditional bluegrass elements with their own, distinctive, trio-oriented vocals and selection of material.

Much of the success of this band can be attributed to two factors: the interaction of superb individual talents within the group and their shared appreciation and devotion to the mastery of a particular bluegrass “sound” — that of Bill Monroe. Yet it is not slavish imitation we are speaking of here — in fact, the group is readily distinguishable from the various Monroe bands of past and present—but a selective, respectful application of Monroe principles to their own musical approach. Of course, many other bands have attempted to do the same thing with varying degrees of success. In certain groups, however, the fusion of these elements has resulted in an exciting, dynamic band chemistry —the little something “extra” that all good bands have in common. This is one of those groups.

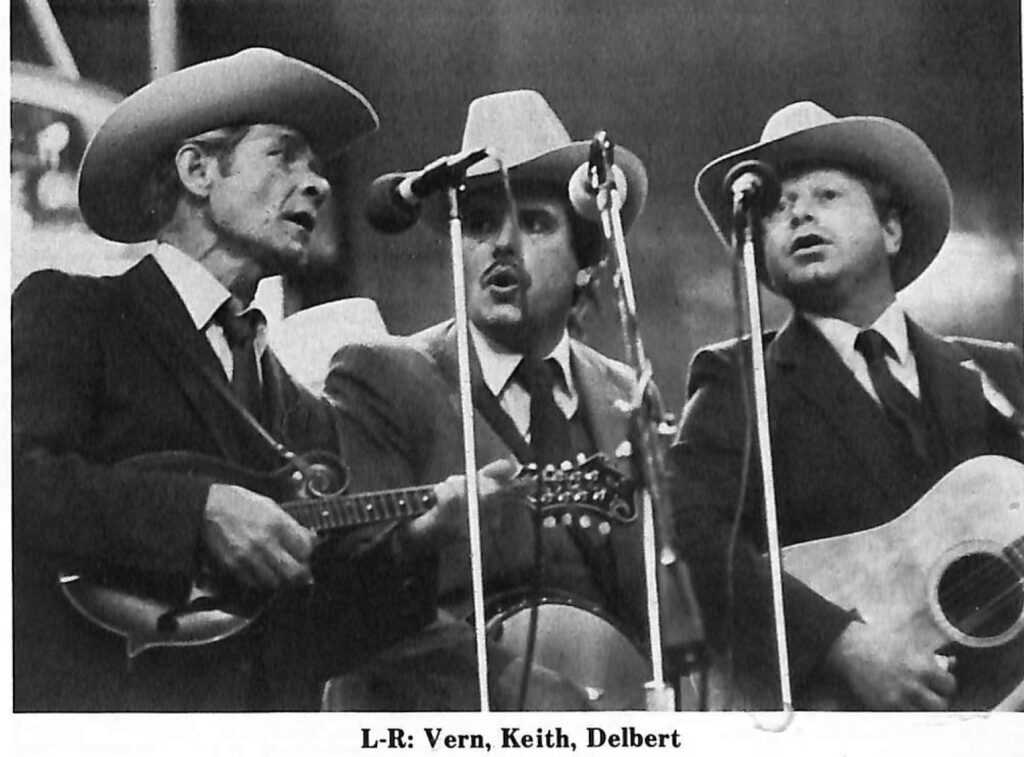

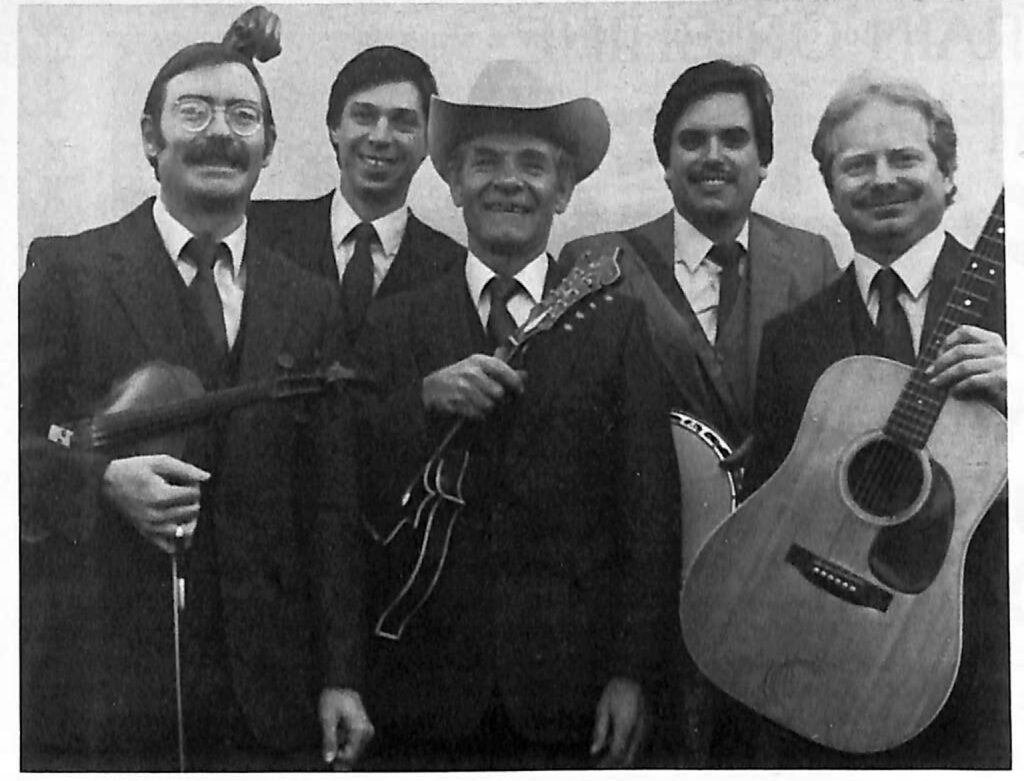

After talking with Vern Williams it becomes apparent that none of this has happened by accident. Vern has studied the bluegrass musical form in some depth and has a thorough understanding of what makes bands “click.” From his early association with Ray Park, as Vern & Ray, through a variety of personnel changes culminating in the current edition of the group — which includes son Delbert on guitar, banjo-player Keith Little, fiddler Ed Neff, and bassist Kevin Thompson — Vern has displayed an uncanny ability to select the “right” blend of musicians to compliment his lonesome Arkansas tenor and solid, but thrifty, mandolin playing. While each member of the Vern Williams Band is capable of drawing attention to their own formidable abilities it is the understanding of the importance of playing “as a band” that really sets this group apart from other perhaps flashier, but ultimately less interesting, bands. •

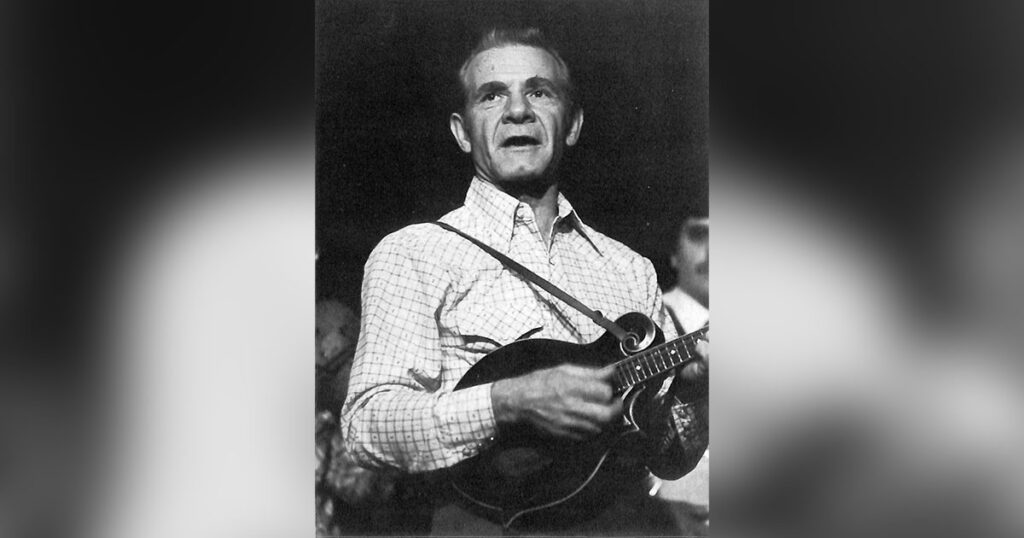

In the final analysis, though, it is really Vern Williams who ties it all together and provides the focus of interest in this exceptional group. His rough-edged, piercing tenor voice comes straight at you without frills or gimmicky note manipulation. Though he is not afraid to arbitrarily experiment with the melodic thread of a bluegrass song “to keep it from getting boring” (take for instance his momentary switch to tenor notes on the second and fourth verses of “Down Among The Budded Roses” from the Rounder album “Bluegrass From the Gold Country” — Rounder 0131), his presentation is always honest and free of contrivance, even when it flies in the face of accepted notions of proper melodic harmony (as it sometimes does).

For students of bluegrass biographies, Vern’s will come as no surprise. In his mid-fifties, he was born and raised on a 40-acre farm in Newton County, Arkansas (“that’s about as close as I can tell you,” he explains, “cause there wasn’t no towns nearby of any size”) the oldest of “five or six children —I have to count ’em there’s so many of us.” His parents still live there and Vern went to see them recently: “Somebody said, ‘Was it good to see your mom and dad?’ and I said, ‘Sure, except it was a little depressing,’ and they said, ‘What’s wrong, are they sick?’ and I said, ‘No, they’re in better shape than I am!”

Vern took an interest at a very early age in the considerable amount of music to be found in the area (“we had to entertain ourselves”) and attributes much of his current ability to this early participation in the all-night dances common to rural Arkansas in the 1930s and ‘40s. “It’s a shame nothin’ like that happens there anymore,” he laments. “It all stopped about 1950. I guess it was television that did it.”

While the all-night musical marathons helped Vern to refine his skills at an early age, it is the recollection of his mother’s singing; around the house that probably has much to do with his presentation of a song and the exceptional amount of feeling he puts into it. “When I sing a lot of those songs on stage I can just go back and remember her singing them around home,” Vern recalls, “and she belted them out, I mean, she wasn’t bashful. She’d be out milkin’ or working in the garden and you could hear her singin’ ‘Clinch Mountain Home’ or a lot of the old Carter Family stuff.”

This early exposure to the songs of the Carter Family made a lasting impression on Vern and he includes many of them in his current repertoire. More importantly perhaps, it taught Vern the importance of vocals which he feels should be the focal point in a bluegrass band around which all other musical efforts revolve. “It’s good to hear some good pickin’,” Vern contends, “but what really counts is when you start to singing the song. When Ray (Park) did his album (“Fiddletown”) he said ‘You know, Vern, I don’t know what I’m gonna do if somebody requests some of those fiddle tunes?’ I told him not to worry about that because nobody is going to request anything else but the two songs he sang on that album (‘Old Dick Potter;’ ‘Bluegrass Music Blues’). I told him, ‘I don’t care how good they are, you’ll probably never have a request to play one of those hot fiddle tunes. What they’ll remember is those two vocals, and that’s what they’ll want to hear.’ ”

Vern’s partiality to singing is evident in his own band, for it is the vocals —primarily Vern’s solo’s, and trios featuring Vern, Delbert, and Keith — that elevate this group to pre-eminent status among West Coast bands. This is not to detract from the instrumental side of the band, for the Kenny Baker-Bobby Hicks influenced fiddling of Ed Neff, and the crisp, accented banjo-playing of Keith Little are remarkable for their drive, taste, and sensitivity to over-all band dynamics. Additionally, the backup playing of both individuals is always an unobtrusive compliment to the powerful vocals. Because of the strong vocals, it is not unusual to see Vern standing a good foot or two from the microphone to avoid distortion during his solos and the trios can be overwhelming in their raw power. This intense style of delivery does not come easily, Vern feels, and he adds, “You have got to put out a lot of energy. You can’t just stand up there and expect it to come out, you have got to work at it. Like I told a reporter in the (San Francisco) Bay area once who asked me how to sing bluegrass and I said, ‘You just got to pour your guts out and walk around them,’ and they put it in the paper! I was just kidding them, but basically that’s what you got to do.”

Initially, Delbert and Keith only wanted to pick with Vern and not sing. “I never did try to push them into anything,” recalls Vern, “but I did tell them that if they wanted to sing they could, and I told them how to do it. Well, it wasn’t long until we were singin’ together, and it wasn’t long after that that you couldn’t shut them boys up —they wanted to sing everything. And they’re good, too.”

It was during these early jam session that Vern discovered Keith had an old Stephen Foster songbook containing many songs Vern had sung as a child. “We just started to thinking,” Vern remembers, “why can’t we do these songs bluegrass? Like, ‘Oh, Susannah,’ or ‘Old Folks At Home’ (‘Suwannee River’), ‘Old Black Joe,’ stuff like that. I think ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ is one of the best bluegrass songs ever written (on stage, Vern describes Stephen Foster as “the first bluegrass songwriter — although Stephen probably doesn’t know it”). We just like to do songs that somebody else hasn’t worn out.”

Vern’s sincere renditions of old songs is not lost on an audience and his ability to pump life into older material is one of his great talents. “We love what we’re doing,” he notes, “and I think that’s why we work so hard at it. I think everybody in the band feels the same way. We never fuss about which songs to play. I feel real fortunate playing with a group like this, ’cause there’s no friction whatsoever. I don’t know how often that happens in a band. I’d say maybe not very often.”

Because of their single-minded appreciation for a variety of older songs, the band tends to duplicate a minimal number of pieces from one show to the next. Additionally, the availability of a large repertoire of songs affords the band the luxury of a somewhat play-as-you-go approach to their stage presentations. “We definitely do not know what we’re gonna do when we walk out on that stage except for maybe the first few tunes,” Vern says. “I just tell everybody in the band, ‘You be thinkin’ of something to do ’cause I can’t do it all by myself.’ I think if you’re an entertainer and have got to make notes about what you’re gonna do before you go out there and do it, well, then you’re not ready to go out there.”

Many bluegrass singers will tell you the supply of good material seems endless, and the more you sing the more you appreciate songs you might have overlooked in the past. As Vern puts it, “You wonder why you never thought of that old song before.” He was reminded of a Louvin Brothers composition the band has been performing lately, “Bald Knob, Arkansas,” and when I commented the tremendous impact of the Louvin Brothers in bluegrass music, and the relative lack of credit Ira Louvin received as a songwriter, Vern was quick to agree: “Yeah, and wasn’t he a great tenor singer,” he added. Vern remembers listening to the Louvin Brothers on a station out of Chattanooga when he was younger and he says they did a lot of Bill Monroe songs like “Travellin’ This Lonesome Road.” Vern remembers, “It was just the two of them, but boy, some of the singin’ they done, you just couldn’t believe it. Without a doubt they were the best brother duet, but there were other good ones, too.”

After moving to California in the 1950s, following a stint in the Marines, Vern started playing bluegrass with Ray Park around San Francisco. In the early 1960s the duo, with the addition of banjo player Luther Riley, and guitarist Clyde Williamson waxed an extended-play record on the Starday label that is now a prized collector’s item. Among the four songs recorded was an exceptional version of Williamson’s “Cabin On a Mountain” which gained Vern & Ray some notoriety —at least within the bluegrass world —and the song remains standard fare with Vern to this day. In spite of some minor success with the recording Vern & Ray slipped back into relative obscurity after returning to California. They were not to resurface until a critically successful album, “Sounds From The Ozarks,” was released by Old Homestead records in the 1970s. Subsequently, the pair went their own way although they still get together informally and collaborated on the first of two albums Vern has recorded with Rose Maddox. There is also talk of a Vern & Ray reunion album. In any event, the early recordings of the pair served to cement the name Vern & Ray in the consciousness of bluegrass afficionados — a fact of life not lost on either of them: “Me and Ray’s talked about that,” Vern reveals, “and we both know that. I don’t know how that all happened but me and Ray never did think we was doin’ anything at the time. We was just playin’ music. We loved it! Now it seems I’ll be talking to someone and they don’t know who Vern Williams is, but if I say ‘Do you remember Vern & Ray,’ they say, ‘Oh, really!’ And Ray’s had it happen, too.”

In spite of the musical demise of Vern & Ray, and various personnel changes since, Vern has managed to retain an authentic, old-time sound in his music. I pointed out the fact that, while they may come easily and naturally to him, many younger groups struggle to recreate the classic sound of the recordings made during the so-called “golden years of bluegrass” —the ‘40s and ‘50s. I asked him if it was possible that modern performers had more difficulty with the songs because they weren’t “living” the songs like they used to. “Technically, the modern stuff is much better than the older stuff,” Vern responded. “But it don’t say as much. The times have changed so much—everything, has got so advanced—and nobody has the time anymore. Back in those days all people had to do was maybe sit around on the front porch and pick all day. They’re bound to come up with something! I admire bands like the Johnson Mountain Boys and other young groups for trying to do the real thing, and play it where I can understand it. I’ve told everybody in my band time and time again—and they understand what I’m saying—I say, ‘Boys, keep it simple, ’cause I’m a simple person, and if you’re gonna play “Sally Goodin’,” for God’s sake, let’s make it sound like “Sally Goodin.” ’

When asked what Vern thought about the common complaint that ‘Bluegrass all sounds alike’, or the related irony that Earl Scruggs’ influence on banjo-players has become so extensive that some people have a tendency to dismiss disciples of his method with comments like, ‘Oh, he (or she) sounds like every other banjo player—“If a banjo player is goin’ to be playing bluegrass,” Vern believes, “he’s going to have to sound like a whole lot of banjo players. Not just like Earl Scruggs, but Ralph Stanley, J.D. Crowe, Don Stover, thousands of them. They don’t sound alike. They’re all playing down-to-earth, but they’re all different. I know I’ve had people say the same thing; that bluegrass all starts to sound the same. But maybe they’re not listening quite close enough. There is a difference if the band knows what it’s doing. Like Ed [Neff] told me one time —and if I’d thought of it this is how I would have said it—he said, ‘When you walk up to a stage and there’s a band playing, you should be able to recognize right away what song they’re playing.’ But with a lot of bands you can’t. You might have to wait until they sing a verse or two before you know what they’re playing. That’s the reason we’re playing with Ed. He believes in playing the melody.”

Recently, the band has helped Rose Maddox to record a couple of well- received albums, and Vern’s bluegrass influence is evident in the modified- country style Rose adopts on the two discs. “She asked us to back her up on those albums, and we turned them into bluegrass,” Vern recalls with a smile. “Originally, we were asked to back her up at a festival in San Francisco. I’d heard she was real hard to work with and the band was kind of dreading it, so I told them, ‘I tell you what we’ll do. We’ll just go out and do the best we can, and if Rose gives us any lip we’ll just let her do it by herself. We’ll just walk off the stage.’ So the first thing that happens is we get up on stage and she kicked off with “Rocky Top” and before we’d done three or four songs I could see Delbert and Keith was just dyin’ to join her on the chorus. Pretty soon she noticed, too, and she motioned them in and you’d think they’d been singing together for months or years. Boy, she just lit up. The main thing Rose liked about us was we wasn’t bashful. We’ve laughed a lot about all this. Rose and I, and we’ve been great friends ever since.”

The forceful, out-front presentation of the Vern Williams Band, that attracted Rose Maddox, is evidence once again of the group’s kinship with Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. Many of the same things are there: high, lonesome vocals; faithful interpretation of melody; bluesy orientation; driving instrumentals; the emphasis on “playing as a band.” All of these things are solidly rooted in Monroe tradition and Vern’s incorporation of these principles, and respect for them, is evident. He is also quick to point to Monroe’s songwriting ability (“He wrote so many of the real good —as far as I’m concerned, the best — bluegrass”) and the fact that Bill for the most part resisted the commercializing pressures of the Nashville recording industry. “I guess he was just too stubborn,” Vern notes, with the hint of a twinkle in his eye. “I don’t know why, but from the first his music always did stand way out from everybody else,” Vern states, recalling the years he first heard Monroe on the Opry while Stringbean was still playing the banjo for him (the early 1940s). “You’d listen to somebody like Roy Acuff, and he was good, but Bill’s music was just a little bit different. It had that crisp, clear sound that I loved. There have been a lot of great ones but to me, Bill is still the best.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Love Vern Williams! I consider him to be the Godfather of west coast bluegrass.