Home > Articles > The Archives > Vassar Clements—Out West

Vassar Clements—Out West

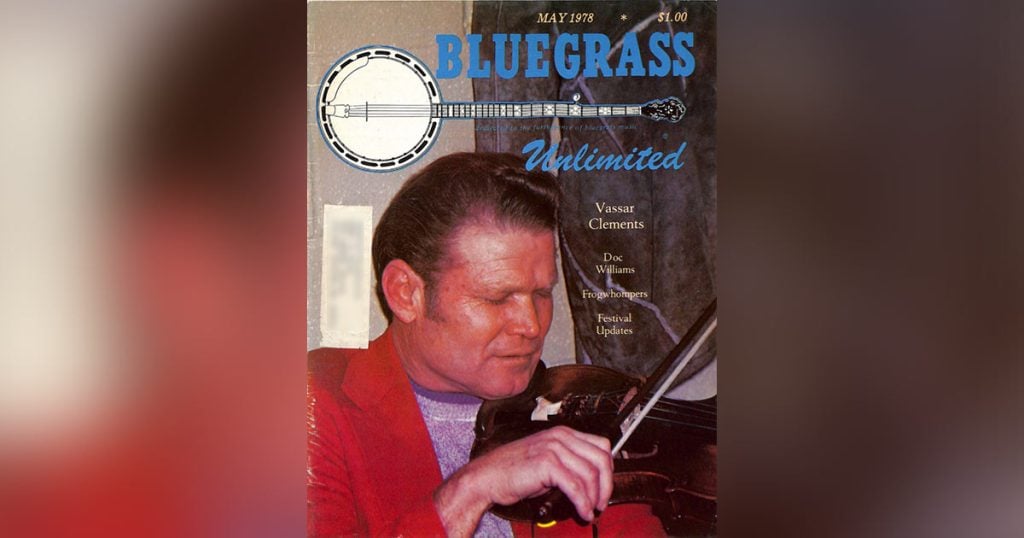

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1978, Volume 12, Number 11

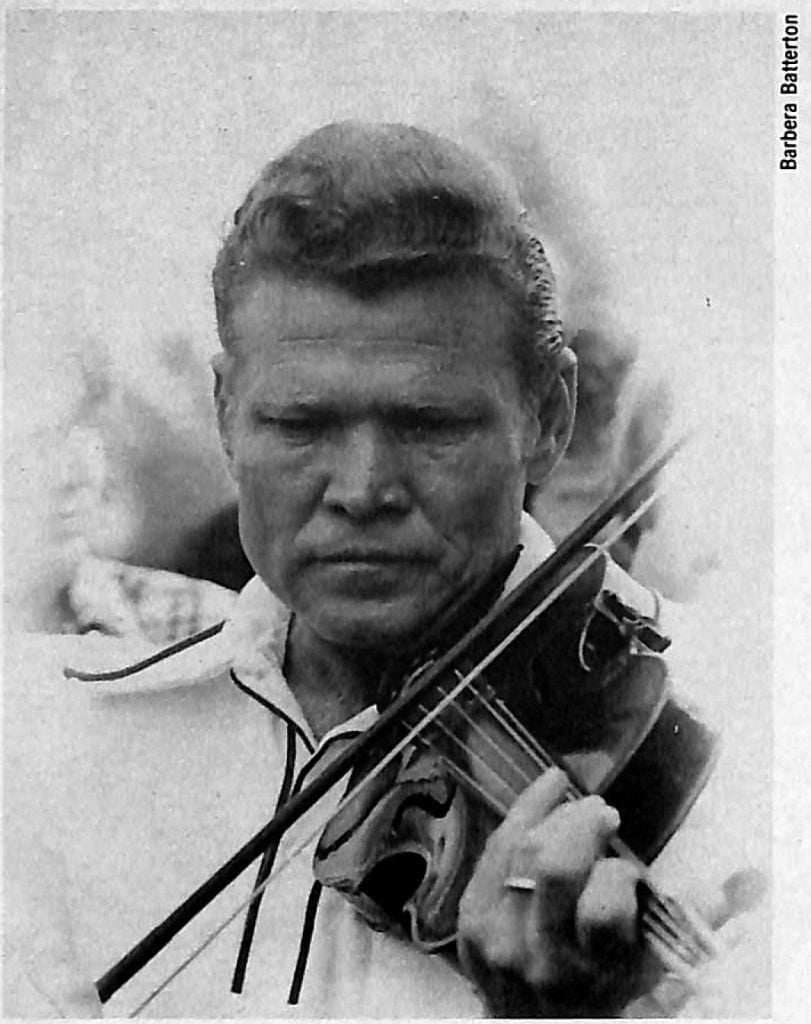

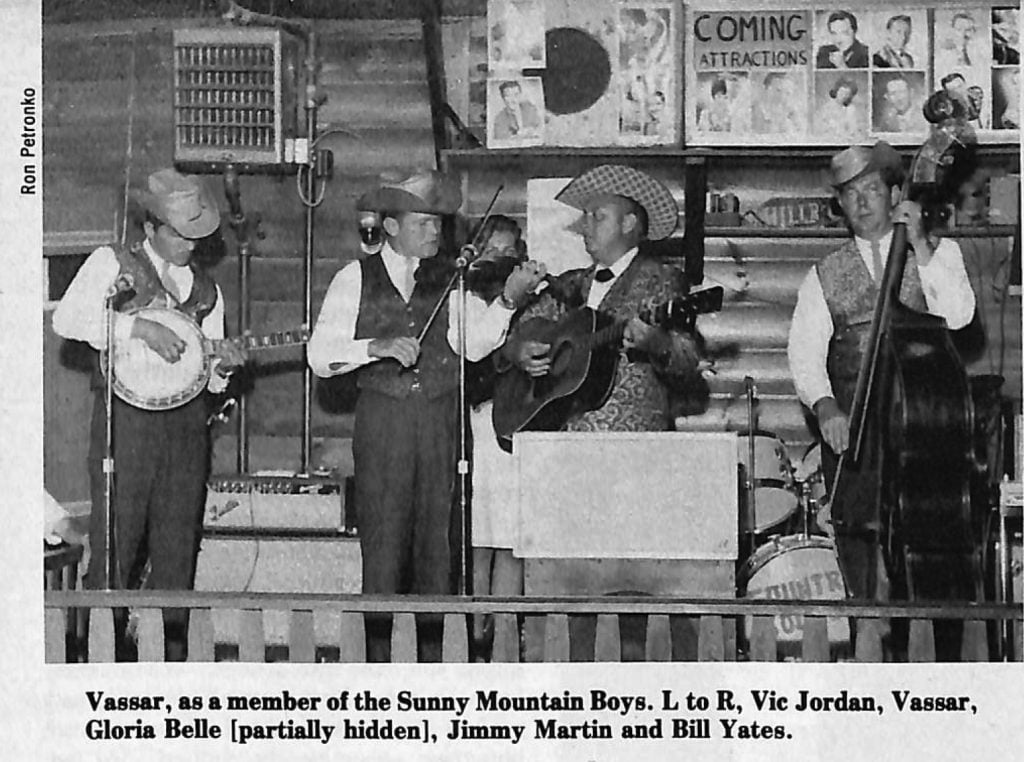

Vassar Clements is one of the best known and popular fiddlers in all areas of country music and is quickly becoming a favorite of jazz and rock players and fans. A complete list of his credits would be as long as a moderate-sized article and would show him as sideman for such diverse talents as Bill Monroe, The Grateful Dead, Jim and Jesse, The Allman Bros., Jimmy Martin and Dickie Betts among others.

During this past May, The Vassar Clements Band played in Los Angeles. A week before the May 1 “Cal State Banjo, Fiddle and Guitar Festival” (which Vassar was headlining), I got word that a band I had been playing in (Pat Cloud’s Bluegrass Turnaround) would be playing at the festival. Obviously overjoyed, I began an intensive campaign to find out as much as I could about the man and his music. There is little written about Vassar, and virtually nothing within the last three years.

Fortunately, former rodeo ace, Rick Kennedy—Vassar’s road manager, was amiable and very understanding. After a brief trip to the dressing room Rick assured me that Vassar would be happy to give an interview.

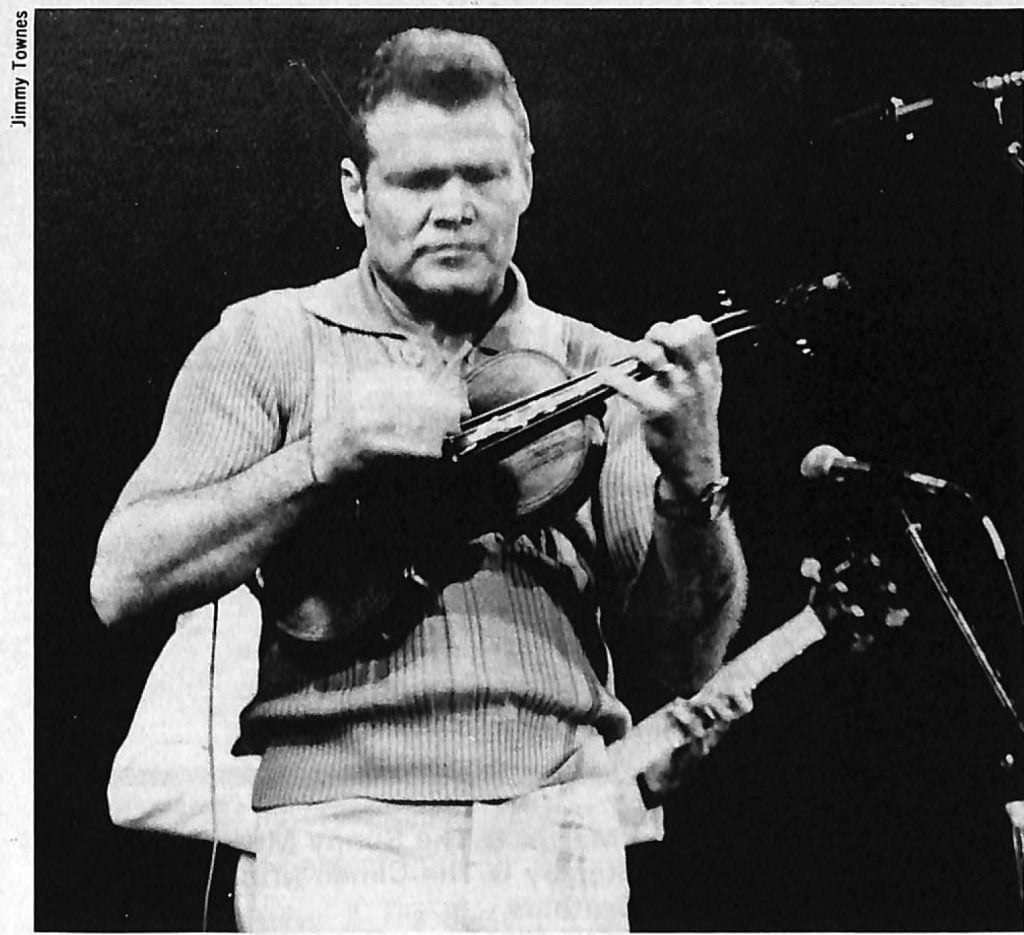

Flanking the doorway were two foreboding-looking characters who turned out to be pedal steel magician Doug Jernigan and the driver of the bus. Vassar was standing, playing that magnificent old trademark instrument of his, fooling around with a series of disjointed licks. I felt nailed to the floor. (Author’s personal digression, totally immaterial to the rest of the article: I was out of music for five-and-a-half years; it was the playing of Vassar Clements on “Will The Circle Be Unbroken?” that got me interested in playing music again. I wore out my first copy of “Circle” in less than a year though to this day I can’t play more than a few of Vassar’s breaks—and nowhere near as well! This man was my first second-time out musical hero and his very presence to me was awesome.). Though we talked for a few hours over the two days, I was never able to completely relax around him.

Vassar, like many of today’s best musicians, began playing the instrument for which he is best known early in life. His first major musical influence was “Chubby” Wise. “I thought that was the prettiest I had ever heard and I still think it is. He could play the smoothest and get the most out of bluegrass music-what he was playing at the time; I’ve never heard anything that can come up to it.”

Virtually every bluegrasser knows when Vassar’s professional career began: “I was about fourteen. At first I could have had a job with Bill Monroe playing guitar, but my mother wouldn’t even think about me leaving school, even if I sent my lessons in. Between then and the next year, I kept on at her and when I got another chance at it I went—but I didn’t stay away from home long; I kept going back and forth. I was in and out of Monroe’s band for years (1949-56) and then with Jim and Jesse (1958-61).

“After that I got out of it for a while; I knew I wouldn’t get out of it altogether-even if it was just to play around the house—I just didn’t think I wanted to go on the road much.”

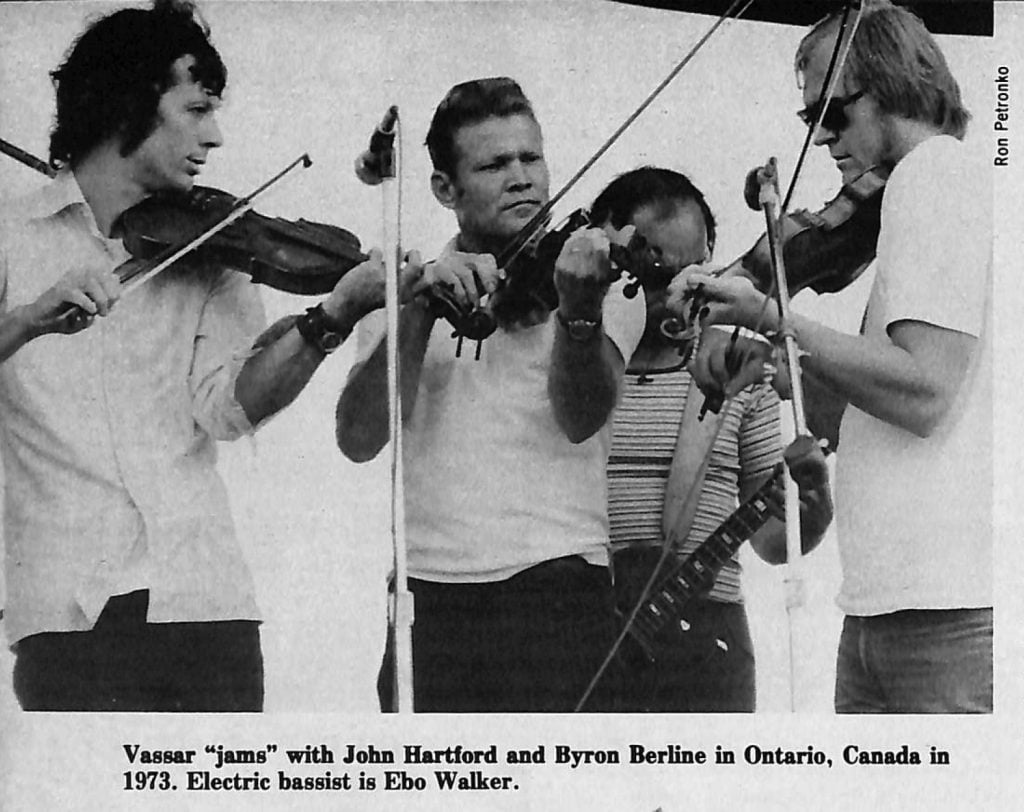

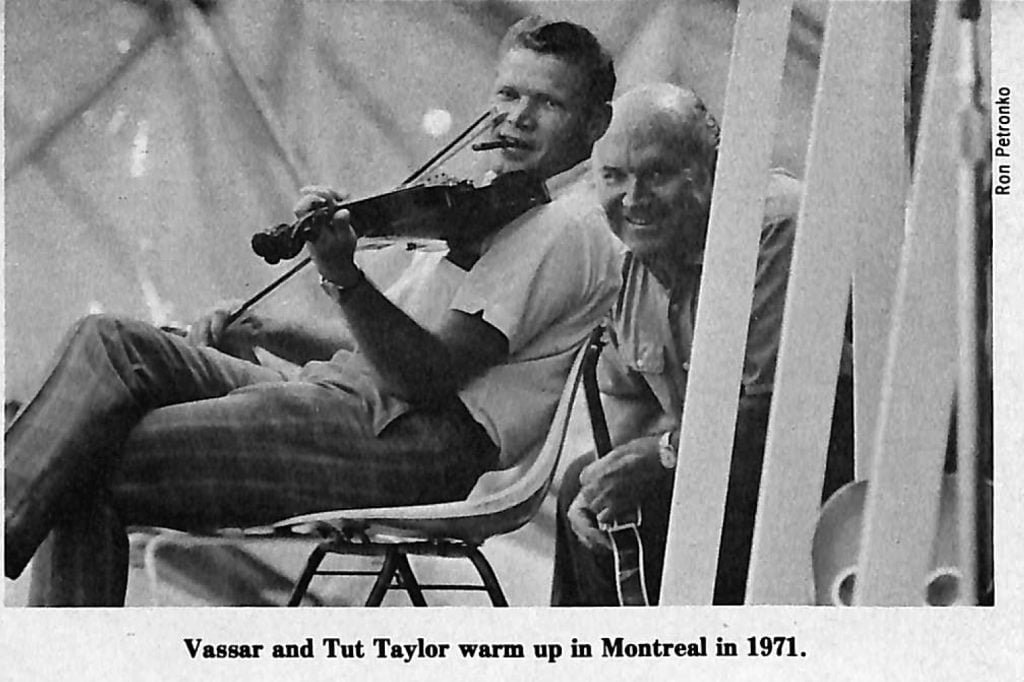

His return to the life of a working musician seemed to pick up where it had left off. After short spells with Faron Young and Jimmy Martin he went with John Hartford, “and that kind of put a different light on things. John Hartford and Jim and Jesse are the best people and the straightest people—the rest of them I worked with was good people and straight people—but I’m talking about right down the line, you couldn’t find anything wrong with them. I worked with the Earl Scruggs Revue for a while, and then I did that ‘Circle’ album and that kind of made up my mind for me about staying with the music.

“There was hardly any rehearsal on it; (The “Circle” Album) it just sort of came together in the studio. The different people each had four tunes, so it was a different kind of thing after each person did their four tunes and you could look for something new. That kept it interesting all the way through; then I started working with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band.”

Vassar was on the road again—with a vengeance. The Dirt Band covered the U.S., Canada, Europe and Japan at least once during Vassar’s tenure. “The Japanese pickers have the finest touch on instruments I’ve ever seen, and I didn’t hear a bad singer—they all had good voices. It was amazing how much they were into American music. I couldn’t communicate very well there, except through music. I’d go out and jam—I jammed every night—but I couldn’t understand a word that was being said! When we’d get through I couldn’t tell them I wanted to go, so I’d put my fiddle away. Then they’d take me to the cab and say something and I’d be on my way back to the hotel.”

In 1975 Vassar formed his first band and had one of his busiest years as a session man; last year he was so busy with the band he had virtually no time for studio work. One of the last sessions, “The David Grisman Rounder Album,” was one of the more difficult in the last few years. “David likes to go over things a lot, but a few times I lost the feel of it—I’d done everything I could two or three different ways. David likes to jam; I like to jam, but we was gonna make a record and I wanted to get things down. I had a great time, though. Grisman’s somethin’ else. That was another session where we had no rehearsal, except in the studio.”

Vassar noted that he is the only fiddler “in my immediate family. I’ll go see my uncle and I’ll play guitar with him playing fiddle, ‘cause if I play fiddle he says, ‘Now that’s not the way you used to play it; I don’t think it goes like that, Vassar.’”

Since 1967 when Vassar emerged from semi-retirement he’s been hearing that from virtually everyone in country music, and by now he’s getting used to it, because the further he gets from the way he “used to play it,” the greater the response his music seems to receive.

Three years ago, Vassar declared, “I am a fanatic about listening to rhythm. I depend on it because I play a lot of notes and don’t play time with my bow I listen for it because a lot of my notes might run over into others.” When asked his reason for hiring an all-electric band with a drummer instead of an all-star bluegrass ensemble, he replied, “To get more rhythm, ‘cause it’s hard to hear it acoustically unless you’re in a room. You can get on stage outside and it’s almost impossible (to hear) because monitors are never right.

“We’re getting a good response; I’m glad it’s been like it has because we play to more people. Any kind of good music is good, and I think it can draw a certain number of people. It seems that this kind of music draws more people, why I don’t know—maybe they can boogie more to this—but then it goes back to rhythm; long as you got that good rhythm—that’s what I want to play.

“When it’s not too loud out there it’s fine, but that two, three months when I played with Dickie Betts—bless his heart, I think the world of him—but that hurt all the way to my toes! There was a bass, two sets of drums, Dickie’s guitar and I was in the middle. It’d just jar you all the way down. I had no more idea of what I was playin’ than nothin’. For at least thirty minutes after the show I couldn’t hear a thing.”

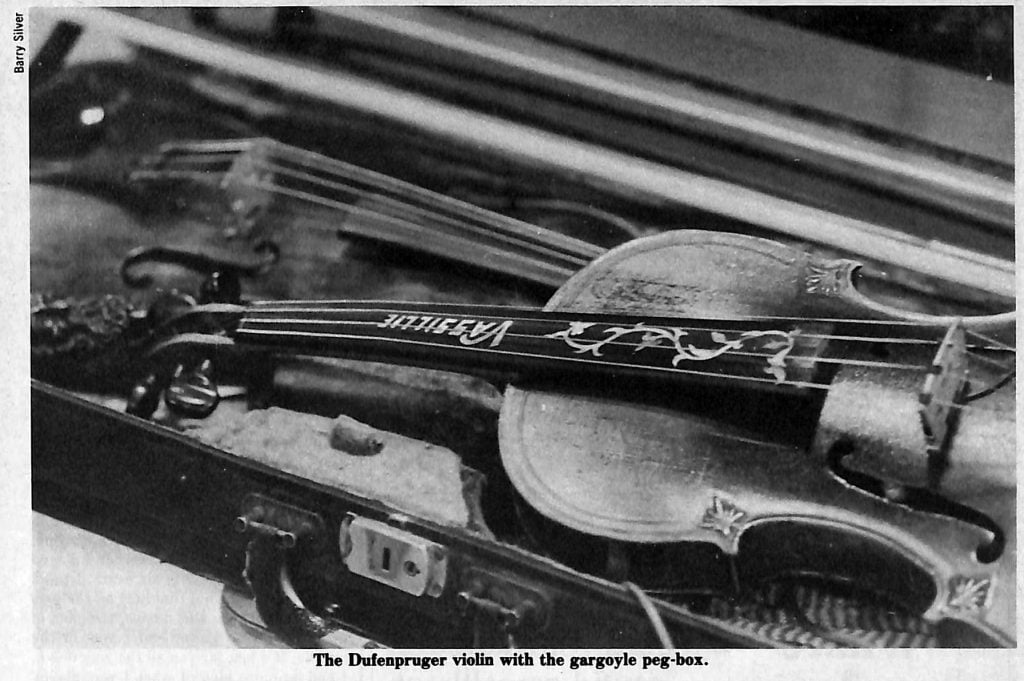

I had always been curious about the history of Vassar’s fiddle (actually he has two; the other has a gargoyle head on the pegbox). “It was made in the last part of the 1500’s by a guy named Dufenpruger.” Vassar believes the head to be the likeness of the man who commissioned the making of the instrument. “Roy Acuff used to own the fiddle. John Hartford gave it to me. He bought it from George Gruhn, then gave it to me.”

Fans of Vassar Clements have been introduced to his wife Millie as his musical collaborator. She is more a personal manager to her husband. “I sometimes come up with melodies or a tempo or I’ll ask ‘can you do this on this?’ and he puts it all together. Musically, the terminology, well, I’m out of that. We were just talking on the bus and I said that I was lucky because Vassar will accept my ideas, or at least give ’em a try; that’s why we work well together. I’m not trying to ‘wear the pants’ or anthing like that. It’s just that I want him to accomplish what he wants, so much that I’m willing to put my efforts into getting it done, so that Vassar doesn’t have to worry about business on top of the music.

“When we first met I was working as a secretary and Vassar was selling real estate and playing bass in a rock band at night. He was having a lot of problems at that time, though I didn’t know it then. Later I came up married to him and I find all this talent and all this trouble inside him. We’d sit and talk back then and I’d say ‘What do you want out of life?’ There’s got to be something buggin’ a man with his kind of talent who’s not using it. Finally he told me that he wanted to get out and play his own thing but he never had the chance; it’s hard for him to talk to people and communicate on that level. He’s just recently got to the point where he can go on stage and run his mouth. It’s often said that if you live with someone long enough something’s bound to rub off, and I think that’s what happened to Vassar.

“The object is to get Vassar’s music out. I’ve become irritated with Nashville people sayin’ ‘We don’t play like that,’ ‘He’s too far ahead,’ ‘What he’s doing won’t fit here,’ ‘Too far-out, too wild,’ and I heard it for five years until I was sick of it! So he went out and found musicians versatile enough where he can play and go in any direction—everything from classical to rock to bluegrass to C & W—with that fiddle he can play in all those different areas and make it sound good and clean and like music and make sense.

“Last year he was so busy with the band he hardly went into a studio at all. He got a lot of calls, but after they’d call so many times they’d finally give up. If Vassar Clements is to be promoted as an artist, why should he sell all these other records for all these other people? Let him do his thing and if that doesn’t work, then he’ll go back to doing sessions. You’re so tired on the road all the time and then you go into a studio and it’s no fun. If it was up to him he’d drag in every time he gets a call because he can’t say no. That’s why, as his manager, I keep things pretty tight because Vassar’s the kind who can’t turn anything down and he’d kill himself in six months with this and that and something else.

“He’s a very emotional person. It’s really serious to him if a fan walks up to him and says, ‘I don’t like what you’re playing’—it really hurts him. I want him to do his best on stage and he can if he doesn’t have to cope with these nutty problems. I hired Rick because things are getting too big for me to handle.”

The band went out to play a scheduled sixty-minute set that ran nearly two-and-a-half hours, Vassar playing encore after encore facing the setting Southern California sun and finally into dark. The Vassar Clements Band is anything but traditional bluegrass: The Dufenpruger violin is electrified as is everything else in the band, including the drums. Doug Jernigan’s pedal steel was the only guitar in the quintet, with electric bass and keyboards—including an ARP (synthesizer)—completing the sound.

The next evening the band headlined a one-nighter at North Hollywood’s Palomino Club. The Pal has hosted most of the biggest names in country and bluegrass music—including Bill Monroe, Waylon Jennings, The Osbornes, Bob Wills, Merle Haggard, Hoyt Axton, New Riders, Country Gazette, The Dillards, Byron Berline and Sundance and the New Grass Revival, among others—during over twenty years in business. Maybe it’s not surprising that L.A.’s bluegrassers were not out in force. Vassar is consciously avoiding playing not only bluegrass but country music as well; he’s playing jazz-rock with country roots—but it’s good jazz-rock and the roots run deep. Vassar’s singing and m.c. work have improved considerably since his first trip to Los Angeles. “Lily Dell,” “Old Black Magic,” ‘‘Turkey In The Straw” (the only traditional tune he played first set, a request from Ronee Blakelee, with whom Vassar worked in the movie, “Nashville”) and “Orange Blossom Special” were the most impressive pieces.

Between sets, I was invited out to the bus to hear a tape of the band’s album. Vassar, Millie, Rick and I talked shop for a while; Millie, Rick and I continuing even after Vassar went back to work. I was treated to another preview, this time of “Vassar Clements: The Bluegrass Sessions” while the second set was in progress inside. When we ventured back into the Pal, we found Vassar in his dressing room with two local fiddlers—jamming, of course.

Vassar’s two main goals he is pursuing for his band: To go and work in Japan, and to “keep learning and keep changing as the times change and as people want to hear it.”