Tyler White Mandolins

Photos by Bud Osborne

DSecades ago, someone approached me at Bean Blossom and asked for feedback on a mandolin he’d built. The F-5 style instrument looked like a C- grade junior high school shop project. Not a smooth curve or straight line anywhere, and the finish looked like he’d melted Crayons over it. I played it a bit, avoiding the sharp fret ends and lumpy frets, and asked how many he’d built, expecting this to be his first or second. “Oh, that’s number 20,” he replied, to my shock.

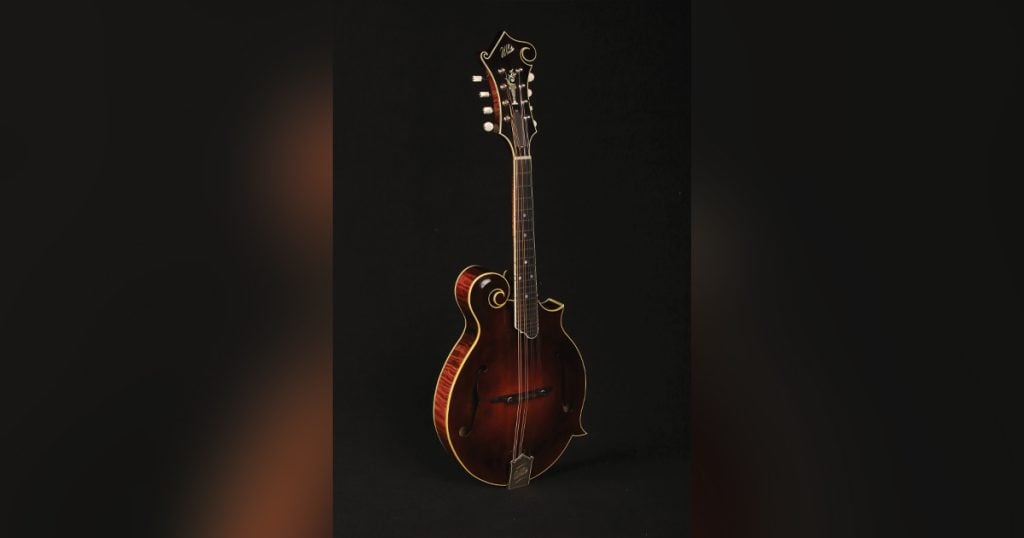

Today, examining the new Tyler White F-5 that White loaned Bluegrass Unlimited for this review—only his 27th mandolin family instrument—elicited the opposite reaction. Parsecs from crude, the instrument demonstrated the finesse, sound, playability and craftsmanship of a more seasoned builder, despite White having built just over two dozen mandolins.

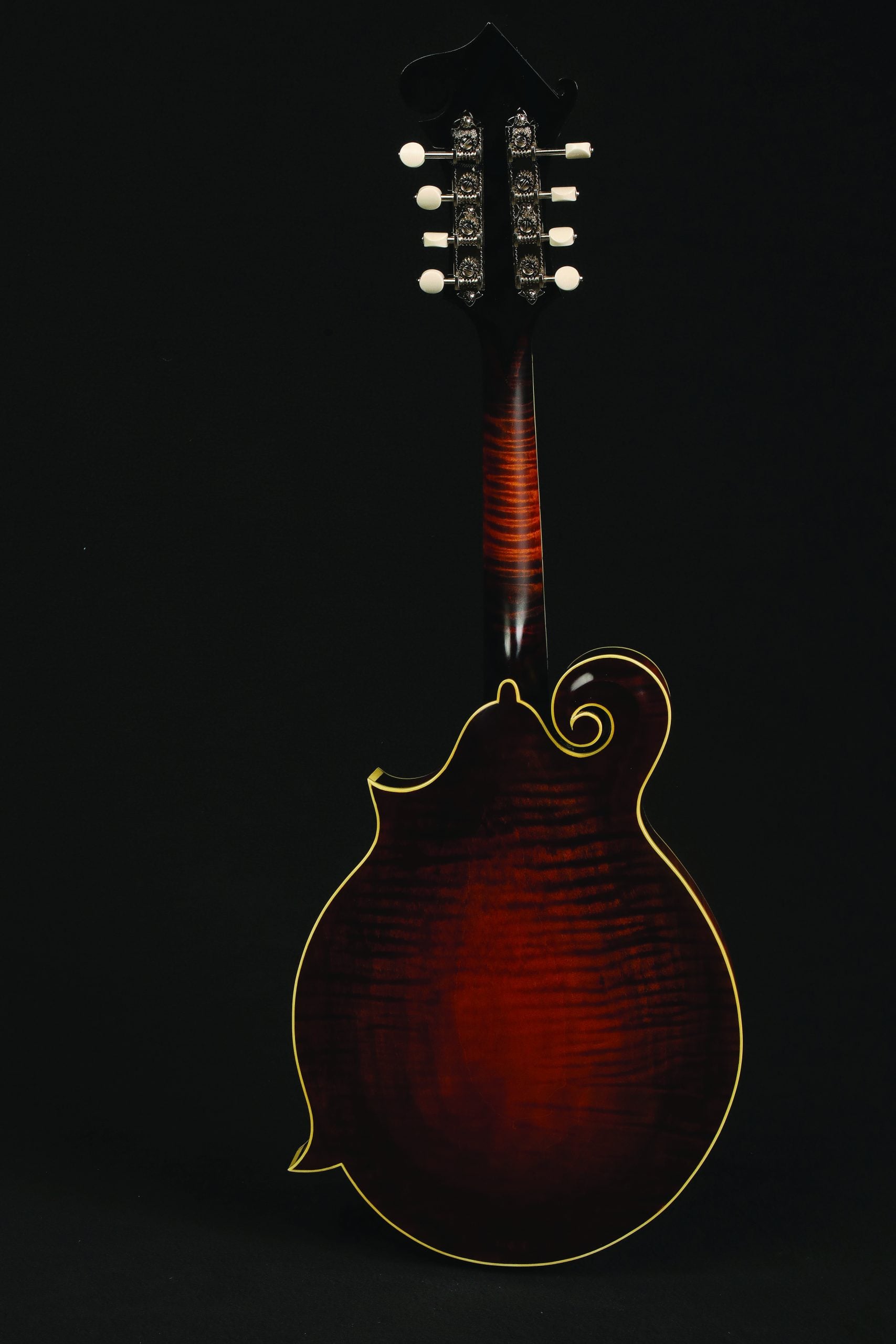

It’s easier to see how he’s progressed so far so fast in the mandolin world when you know that White’s path to professional luthiery started when he founded Pinehouse Guitars several years ago, where he honed his woodworking, fabrication, and finishing skills on a variety of high-end Fender solid-body electric guitar and bass clones. He also gained essential experience with tonewoods from a variety of sources, and has come to appreciate how a luthier can work through set after set from the same tree to develop their skills at bringing the deep tones out of that log, such as the Indiana red maple used here.

“The maple in that instrument’s back and sides came from a stash of local maple I picked up years ago and used for my guitars,” says White, who’s based in Bloomington, Indiana. “That’s my very last set of it.”

His passion for building mandolins started when, on a lark, he ordered a mandolin kit from the legendary Roger Siminoff. White liked the resulting instrument, which he sold, and decided to quit electric guitars to focus on building and selling fine mandolin-family instruments. A quick study, already his quality, attractive price points, and sound have created a two-year backlog of orders.

Housed in a small, very tidy wood shop on his semi-secluded rural property, White focuses on the minimal essentials. He often uses planes and finger planes for precise control and to reduce sawdust. No CNC or thickness sander here: White builds his mandolins in the old school, hands-on tradition. “Although I do rely heavily on hand tools, I also will set up a duplicator in another structure on my property for carving the tops/backs for the sake of graduation consistency,” he tells Bluegrass Unlimited.

As ordered by the customer, the instrument here sports numerous Loar features, including the traditional flat ebony fingerboard with narrow 1920’s-era frets, a minimal, hand-rubbed Cremona-style sunburst, and classic small f-holes, giving it a very Kalamazoo redux feel and sound. The minimal sunburst on the top, back, sides and neck, plus the solitary “White” cursive MOP inlay in the headstock, also add class and artistry to this mandolin. White says the pearl inlay pieces are hand-cut. But he does buy them from a specialized source rather than wasting time doing them himself, time better spent focusing on the instrument’s sound and playability.

One note here from White: “The finish on this mandolin had hand-rubbed stain and varnish, which is an option I’ve given my customers. I can spray the finish for a more ‘perfect’ look, but most of my customers prefer the Old World, less perfect approach. This method does result in more texture or imperfections depending on how you look at it, but it’s also much thinner. It really does depend on what the customer values. Many of my customers have asked that it look old right out of the box. Not ‘reliced’, but not brand new as was the case with #27. That being said, I do offer a more pristine finish option where the varnish is applied with a spray gun. It’s more glossy and there’s no texture or divots.”

Probably because he started his professional career building high-end Fender clones where set-up and playability are paramount for drawing and gaining repeat customers, this White mandolin played very smoothly. The mandolin’s intonation was excellent, measuring only about 10 cents sharp on each string course. Nothing serious, but the new owner might want a slight adjustment to the bridge position or some detail work on the nut and saddle edges to correct that. The fretwork was expectedly immaculate from a builder used to catering to the demands of high-end electric guitarists, with superior playability up and down the neck.

Getting to the heart of the question, how does it sound? As an absolutely brand-new instrument with a stiff Adirondack top, there’s plenty of pop, punch and sparkle here. This White F-5 already has the power to cut through a big jam or to project well over a mic in a stage setting, but its bottom end response will take just a bit of playing time to open up and bloom: typical for Adirondack-topped instruments. Once broken-in, this mandolin, a bargain at this price, should satisfy almost any player.

White’s F-5 mandolins, which retail for $6,200, come with a hand-applied varnish finish, a Calton case, and an engraved James tailpiece. For orders coming in now, Waverly tuners are standard instead of the Gotohs found here. Of course, more modern features such as a radius fingerboard and larger frets, and more elaborate headstock inlays, are available, and he also offers Airloom Recurve cases by Northfield.

Tyler White has found the skills and passion to evolve from building relatively simple solid-body electrics to crafting top-quality mandolin family instruments – maybe the most demanding challenge in bluegrass luthiery – in a short time. On his workbench sat a stunning H-5 mandola in the white with a full torch and wire inlay. His repertoire also includes A models and perhaps two-point mandolas, but not octave mandolins in the future, he says, because of the low demand. For more information, visit www.whitemandolins.com.