Home > Articles > The Tradition > Tony Rice & The Grisman Years

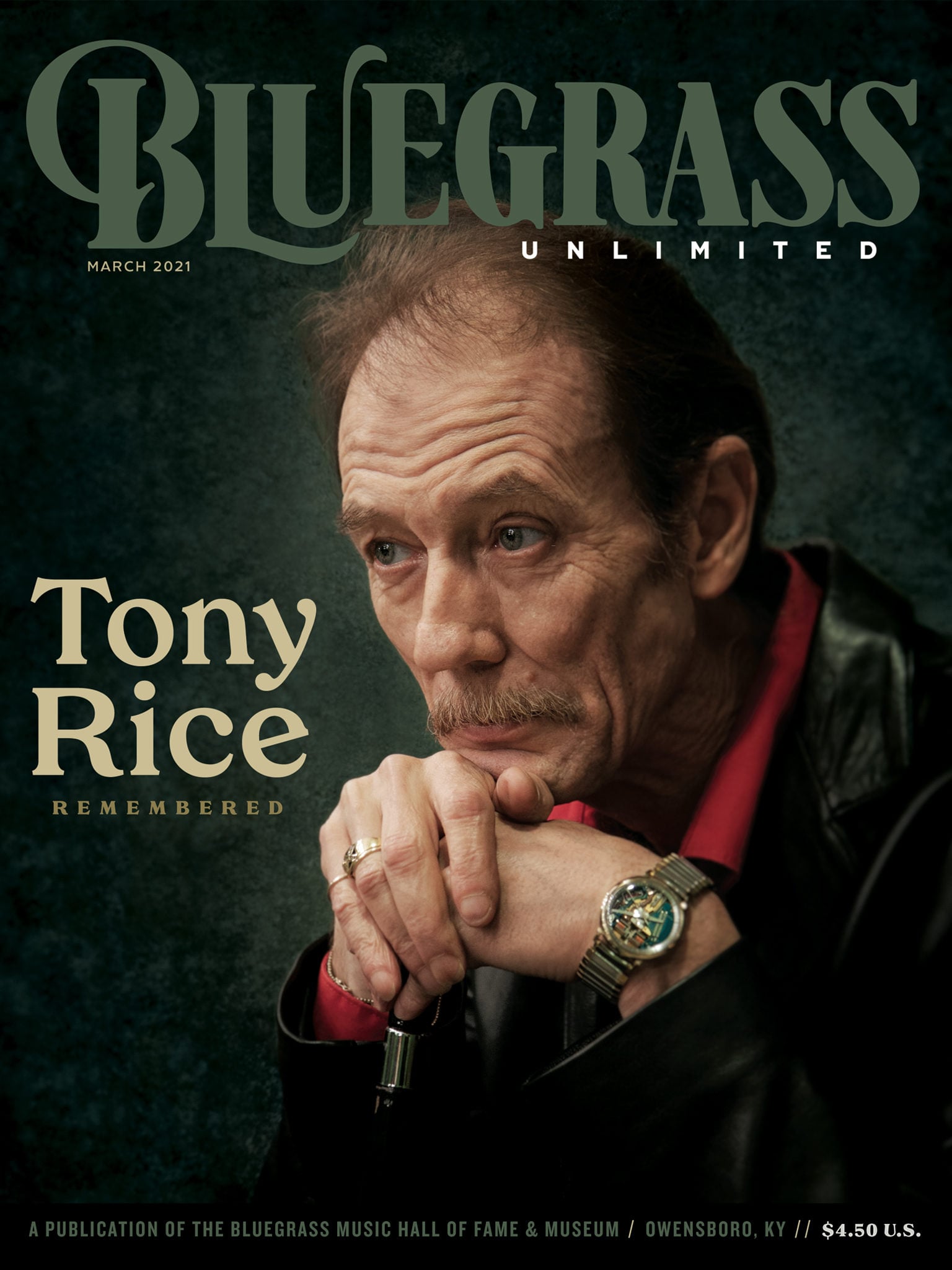

Tony Rice & The Grisman Years

During a video interview with Bryan Sutton, which was broadcast online shortly after Tony Rice’s passing, Blue Highway guitarist—and Tony Rice biographer—Tim Stafford pointed to three “schools” of Tony Rice’s development as a guitar player. The first occurred during Tony’s early years, when he was greatly influenced by Clarence White. The second was when he performed with J. D. Crowe in the early 1970s. The third occurred during the years Tony spent with David Grisman in the late 1970s. It was an astute observation which holds a lot of truth.

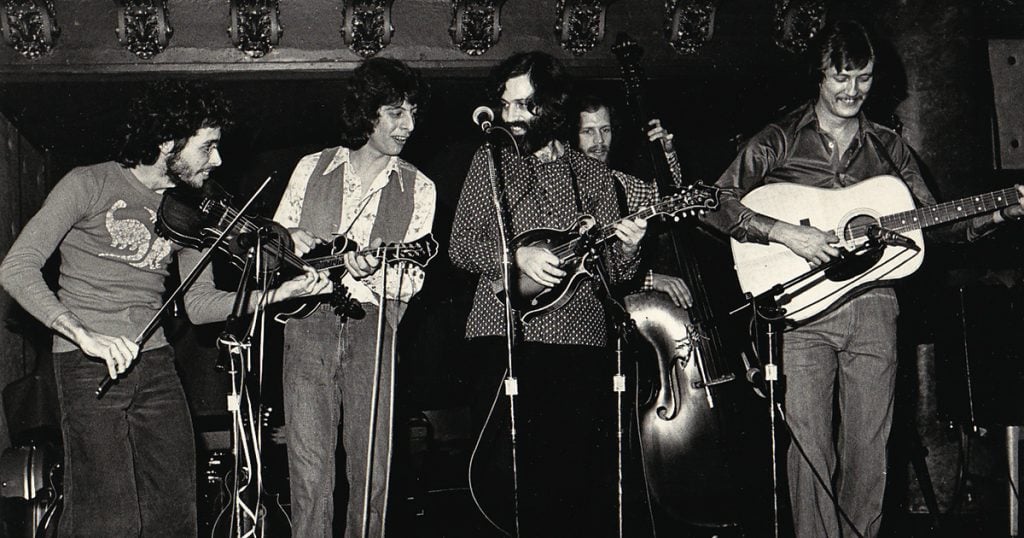

A few years ago, someone gave me a bootleg disc of one of the early live performances of the David Grisman Quintet. During the show, Grisman introduces the band members and then points to John Carlini—who was in the audience and was the band’s musical director—as the “sixth member of the band.” While the five band members who were on stage that night, which included Tony Rice, have been strongly associated with the group