Home > Articles > The Archives > Tony Rice: East Meets West

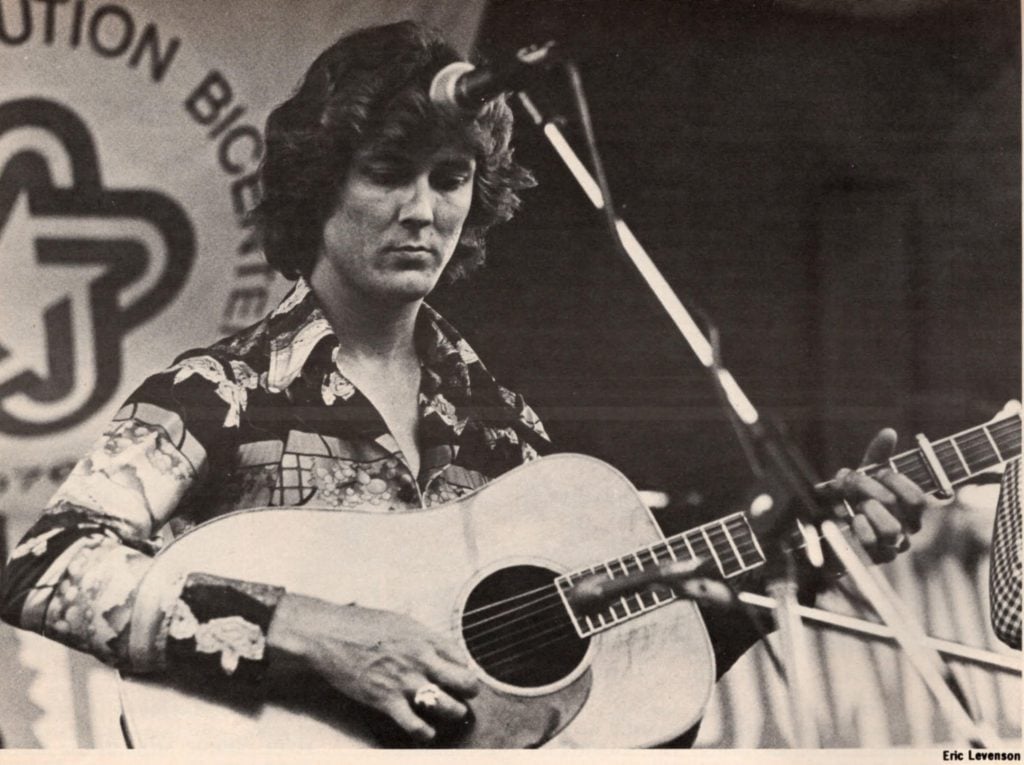

Tony Rice: East Meets West

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1977. Volume 12, Number 4

It was a hot September evening in Louisville, Kentucky seven years ago when I first met a skinny teenage guitar player named Tony Rice. He had just landed his first job with a full-time bluegrass band and was obviously totally immersed in music.

Tony’s new employer—the Bluegrass Alliance—was a young group which, had begun making quite a name for itself with a distinctive approach to modern bluegrass. It had adapted some excellent material from outside bluegrass (like “One Tin Soldier”, “West Montana Hannah” and “Ruben James”) and had co-opted a number of musical ideas from rock. The Alliance was, nevertheless, well within the borders of bluegrass; it was no further afield in its way than were the Country Gentlemen, Emerson and Waldron, or the Osborne Brothers.

The group had just lost one of its prime assets—Dan Crary. Dan was a strong singer and an exceptional guitar player. His rhythm work was full, solid and consistently appropriate. It was, however, his lead guitar which most amazed and delighted the band’s audiences. He could play a demanding fiddle tune like “Dusty Miller”, exciting breaks for one of his vocals like “Little Sadie” or a flurry of playfully hot fills for the introduction to “Freeborn Man”. Whichever it might be, the crowd loved it.

Dan’s playing showed a remarkable sense of melody, originality and technique. His tone and clarity were excellent. Even more impressive was the sheer power of Dan’s playing. Although many performers find that lead guitar is weaker than banjo, mandolin or fiddle, Dan calmly sent his solos booming into the audience at volume equaling or surpassing the other instruments in the band.

In short, the shoes Tony Rice was stepping into were sizeable, especially for a teenager making his first attempt to join the difficult world of professional music. Tony, for his part, had played only rhythm guitar with various informal groups from time to time. He had, however, been working on his own concept of lead playing in private and had come up with quite a number of interesting and original licks. Sitting in his room, he played some extremely nice guitar breaks.

Tony was appreciative of Dan’s ability and achievements. He played Dan’s solo guitar album “Dan Crary” (American Heritage 27), for me, and pointed out some of the especially interesting licks. He then picked up his own guitar and played one of the tunes from the album, “Ruben’s Train”, using some of Crary’s ideas and some of his own.

On stage with band, Tony showed that he had a good singing voice-high and clear. It was not yet fully developed, but showed abundant potential for strength, range and expression.

His guitar playing was good, but—on the few solos he played—considerably more conservative than the things he had played earlier at home. It was also a bit quiet, and the listener was forced to strain in order to hear what he was playing. In short, Tony clearly had plenty of musical ability, but it was early to judge how far he would go with it.

The rest of the Bluegrass Alliance at that time consisted of Sam Bush (mandolin), Lonnie Peerce (fiddle), Buddy Spurlock (banjo) (soon to be replaced by Courtney Johnson) and Ebo Walker (bass). Sam and Tony seemed to have particular affinity for each other, and I was surprised to hear them say that they rarely listened to bluegrass music, but rather to rock and jazz. This was confirmed later by listening to rock and roll on the car radio as we drove around town and by visiting a nearby rock/jazz record store with them. I began to suspect that both Sam and Tony might be shortly going the way of Clarence White, Bill Keith, Peter Rowan and Richard Greene—out of bluegrass and into other musical fields.*

[*The musicians mentioned were among the most creative younger pickers to emerge on the bluegrass scene during the 1960’s. Bill Keith, after working with Red Allen and with Bill Monroe, played plectrum style banjo with the Kweskin Jug Band and, later, accompanied various folk performers on pedal steel. Clarence White set aside his acoustic guitar for a solid body electric and a job with the Byrds. Peter Rowan and Richard Greene had also quit Bill Monroe to do a variety of non-bluegrass music, including a stint with the rock group Seatrain. Interestingly enough, each subsequently returned to make additional significant contributions to bluegrass.]

As it turned out, Tony was not close to abandoning bluegrass—far from it. Over the next five years, first with the Alliance and then with J. D. Crowe and the New South, Tony would evolve into one of the most exciting and influential guitarists ever to play bluegrass. And-—as if this were not enough—Tony concurrently established himself as a top bluegrass vocalist with an awesome mastery over traditional and modern material.

Tony’s achievements clearly grew in large measure from a combination of native ability and a great deal of hard work. He also profited from a number of important personal contacts over the years.

The first of these came from within Tony’s own family. His father, Herbert Rice, was a heli-arc welder from Gaston County, North Carolina who played mandolin and guitar in his spare time.

“In his very young days,” explains Tony, “pure bluegrass was definitely at its hottest-which of course was Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs playing together. It’s really weird how many people haven’t heard that music. But if they haven’t heard that, they don’t know the real thing.

“The first music that I ever heard—pure bluegrass that turned me on—was the old Flatt and Scruggs stuff. We had a 78 of ‘Foggy Mountain Special’ and the other side was ‘You’re Not a Drop in the Bucket’. That was music that really got to me.”

Tony was born June 8, 1951 in Danville, Virginia. (His birthday, as Tony points out, falls the day after that of guitarist Clarence White.) The following year and a half was spent in Newport News, Virginia where his father worked in the shipyard. Then the family moved to Los Angeles, where Tony spent most of his childhood years.

Tony’s earliest memory of live music is of sitting next to his uncle Hal Poindexter who played guitar with the Golden State Boys. That band—started by Tony’s father—was probably the second bluegrass group in southern California.** It was, in Tony’s words, “the first group with really tight vocal harmonies.”

[**The first-as far as Tony knows-was Roland and Clarence White’s group, the Country Boys which was later called the Kentucky Colonels.]

Tony’s father played mandolin; the rest of the band included other uncles of Tony’s: Leon Poindexter, bass and Walter Poindexter, banjo. Later Don Parmley (now with the Bluegrass Cardinals) replaced Walter on banjo.

In this musical environment Tony soon began experimenting with playing. He first tried mandolin, but before long switched to guitar. His public debut was at age 9 on the Town Hall radio show, where he sang the current country hit “Under Your Spell Again”.

On the same show was a young band called the Country Boys, which included a sixteen-year-old guitarist named Clarence White. Although Clarence was not yet playing any of the astounding lead guitar which would make him famous in bluegrass circles, Tony was instantly struck by Clarence’s rhythm work. It was, in Tony’s words, “thoroughly amazing.”

The Country Boys included Clarence’s brothers Roland on mandolin and Eric on bass. Billy Ray Latham was the banjo picker and Leroy Mack played Dobro.

“That was a good band-really great,” recalls Tony. “It’s funny, the D-28 that I now own (the Martin guitar Clarence was playing when Tony first saw him) is the first one I ever saw. The white binding just fascinated me and I was really floored by the tone.”

Interestingly enough, when Clarence later began playing lead guitar with the group he did not use his D-28 for the tunes on which he took solos. Instead, he switched to a D-18 (a less expensive guitar) on these tunes, which struck guitarists in the audience as odd. (Some doubtless began to wonder if their own prize D-28’s were inferior to D-18’s for lead work.)

“Actually,” explains Tony, “Clarence’s D-28 wasn’t in shape to use for lead at all, the neck was so badly warped.” When Tony recently bought the guitar, he had it fully repaired and now finds it performs excellently for both lead and backup.

At any rate, soon after his first radio appearance, Tony began playing in a band with his brothers. Larry Rice played mandolin and Ronnie played bass. Joined by a young banjo player named Andy Evans, they called themselves the Haphazards. They played straight bluegrass material: “Foggy Mountain Breakdown”, “We’ll Meet Again Sweetheart”, etc. At this early stage of development, however, the results were less than totally successful.

“When we sang, we sounded like rats with real high squeaky voices,” remembers Tony with an embarrassed smile. “I sang lead and at various times everybody sang lead in unison, since nobody knew anything different.”

Nevertheless, the group evidently had appeal. “Somehow,” says Tony, “we ended up on this hootenanny circuit with Pete Seeger, and so on. Even as little kids we played at the Ash Grove, the Troubadour, Disneyland and a lot of big auditoriums.”

“Each time we’d end up at a gig with the Country Boys—which happened frequently”, Tony continues, “Clarence would be ten times hotter than the last time we’d seen him. I’d always beg Clarence to let me play his guitar and he would always let me do it. It was the greatest thrill to me.” Clarence would also show Tony guitar licks. “At first I was just uptight at being around anybody who was that good,” concedes Tony. “I was so nervous I didn’t think I was absorbing anything. Then I’d go home and suddenly remember what he’d shown me.”

As Clarence began to develop his new lead playing style Tony learned a few of his breaks —like “Wildwood Flower” and “Black Mountain Rag”—note for note. On the whole, however, Tony learned a very limited amount in this way, and with time replaced Clarence’s phrases with his own way of playing.

For the next four or five years Tony continued playing on and off with his brothers around Los Angeles. Doc Watson began to play in the area, providing Tony with additional musical stimulus, though he continued paying close attention to Clarence as well.

In 1965 the Rices moved back east. Over the next four years they moved repeatedly between Florida, Georgia, Texas, and North Carolina.

Tony continued to be absorbed by music, but there wasn’t much regular performing in a band situation. Although he played periodically with his brothers, his father, and other local musicians, he wasn’t part of an ongoing band. His musical development thus continued chiefly through his own inner resources.

“It was the scene of just hanging out and learning,” Tony explains. “I was very withdrawn, musically, to the outside world. I figured, ‘Well, if there’s no one to play with, then you have to make music yourself.’ And that’s what I did.”

His interest in music, however intense, wasn’t earning Tony anything significant in the way of money. By 1969 he decided to take a day job as an apprentice pipe fitter.

The desire to play remained, though, and the summer of 1970 found him at Carlton Haney’s Reidsville, North Carolina bluegrass festival with the idea of locating some kind of band to play with. And it was here that Tony landed his job with the Bluegrass Alliance.

Working with the band was exciting for Tony, but it was tough at times. During one period when work for the band has all but dried up, Tony was unable to afford his $12-a-week sleeping room. Fortunately, he was able to move in with banjoist Courtney Johnson until things improved.

Tony’s association with Sam Bush, as suggested earlier, was of great importance to him. “He was such a good picker and knew good music too,” says Tony about Sam. “This was something I’d run into with very few people at that time who would open their ears to something else beside straight, old time, down-to-earth bluegrass. Sam and I got on good in that respect because we were turning our ears into any kind of rock, jazz, . .. whatever.”

On September 3, 1971, after exactly a year with the Alliance, Tony left to join J.D. Crowe’s band, the New South. As things turned out, he would remain with that group exactly four years.

Larry Rice, Tony’s older brother, had been playing mandolin with J.D. for the past couple of years. The group’s bassist, Bobby Slone, was also well-known to Tony: Bobby had played bass with the Golden State Boys in California and had toured with the Kentucky Colonels playing fiddle. Nevertheless, Tony’s overriding reason for wanting to join was J. D. himself.

“A lot of people think of J.D. as: ‘Sure he’s a great banjo player,’ ” explains Tony. “But the cat is more far out … he has a tremendous amount of musical knowledge.

“It’s the important musical knowledge that he has,” Tony goes on. “The real important part is to play right perfectly in time, to play with soul, to hit all the notes really clear and clean.

“J.D. has a great influence on my right hand—on my whole theory of attacking a string; how to attack it and when not to attack it; how to get the most tone and volume out of an instrument. I guess I’d say I learned to use the instrument efficiently from J. D. Crowe.”

It wasn’t that J.D. sat down and gave Tony pointers. “I just observed his hand technique. I got a real good chance to look at his hand,” laughs Tony, “since I played standing right next to him for four years. “It used to amaze me that you could hit a string that hard,” he continues more seriously, “without any rattle and get such a pure tone. It really takes practice to do that—just to get a clean, smooth sound—something that’s not jumbled up with the notes all run together.”

J. D. has been known to stress the musical importance of timing, and Tony was also keenly attuned to this aspect of playing. “Most people think too much in terms of metronomic time—of playing like a metronome from the beginning to the end of a tune. “But,” he points out, “you can attack a note before the metronome would strike, or you can attack it after. The feel of music comes from that. It’s not whether or not you’re playing with the metronome: it’s where you’re attacking the notes.”

The rhythmic contribution of a group’s bass player is also of great significance to Tony. “I hate to play without a bass,” he asserts. “If I’m not playing with a bass, I tend to do what he would do—play one, two, three, four. If the bass is there doing it then I feel free to do something else. I can fill in the little tiny holes that are left by most rhythm guitarists.

“Of course,” Tony adds, “I have to credit Clarence White for doing that first—playing in the various places that no one else would ever think of filling in.”

When Tony joined J. D., the band had some of the steadiest work in bluegrass. It performed six nights weekly in the relatively plush lounges of Sheraton, Rodeway, and Holiday Inns in the vicinity of Louisville and Lexington, Kentucky. In the summers it performed on the festival circuit.

The instruments were, however, fully electrified, a prerequisite‚—J. D. seemed to feel—for the club work they were doing. In electrifying the band was following the lead of the Osborne Brothers, whose commercial success appeared to be linked with their having gone electric.

Tony disliked playing with electric pickups on the instruments. He was also convinced that festival audiences, at least, would like the band better unamplified.

“That was a very difficult time for me,” he recalls. “It was frustrating to know that here’s J. D. Crowe and Bobby Slone and Larry—three guys who can really play and sing great bluegrass music. And we’re plugged in—but we could be doing just as good and better if we weren’t.

“On the other hand,” Tony acknowledges, “it paid good. You develop a lifestyle out of this that becomes a circle. You go into a bar and you hook up your instrument on Monday night and play ‘til Saturday night. Then the next week you do the same thing again. This goes on week after week, year after year. You bring home a steady amount of income.” Tony laughs wryly, “I couldn’t do it again.”

Nevertheless, the band did progress musically and continually learned new material. “A club situation is very loose,” explains Tony. “If you want to try a new tune some night when there’s all drunks sitting in the crowd and they don’t know any better, you can try it.

“And once you try it, you can do it again. Especially with J. D. Crowe, it only took about one time to find out what kind of mistakes you’d made. Next time you didn’t make them.”

J. D. Crowe had first attracted attention in the 1950’s as the incredibly powerful banjo that set off Jimmy Martin’s straight-ahead, driving music. When J. D. finally recorded with his own group in the late 1960’s his sound was still well within the scope of traditional bluegrass. To an outsider it would have appeared that J.D. was fully committed to this sound lacking either desire or, perhaps, the flexibility to change with the passage of time.

Tony found him to be otherwise. “J. D. was open to any new ideas,” comments Tony. “I don’t think J. D. had really ever heard the style of rhythm playing I was doing. It took him awhile to get used to it, but after awhile I think he liked it.”

During Tony’s tenure with the group, its repertoire and arrangements shifted markedly from the traditional toward the contemporary. Its next album, “J. D. Crowe and the New South”(Rounder 0044) was an overwhelmingly successful presentation of modern bluegrass.*** It features sophisticated arrangements, inspired lead singing (most of it Tony’s), flawlessly tight and powerful vocal harmonies, and some of the hottest instrumental work around. To someone who has followed J.D. via his previous records, the change was astonishingly abrupt and complete.

[***Larry had left the band by this time and had been replaced by Ricky Skaggs (fiddle and mandolin) and Jerry Douglas (Dobro).]

While the New South album owes its success to all of the musicians involved, Tony’s influence is strong. His playing and singing contributes numerous high points to the album and several of the record’s most outstanding cuts (“Old Home Place”, “You Are What I Am”, “Ten Degrees and Getting Colder”, and “Summer Wages”) were brought by Tony into the band’s repertoire.

In terms of performance, it was hard to decide which was more exciting, Tony’s vocal work or his guitar playing.

His singing had matured remarkably since his days with the Bluegrass Alliance. It was now fuller and more powerful than it had been. Even more important, it possessed a new expressiveness and subtlety. The strength and heartfelt quality of traditional bluegrass singing were still there, but there was a modern feel, especially in the use of dynamics. Tony’s capacity to balance power with restraint and understatement contributes importantly to the impact of his highly individualistic style.

Tony has strong preferences in singing. “Lester Flatt is my favorite bluegrass singer,” he declares firmly, “the old Lester Flatt.” He mentions Flatt’s singing of “Gonna Sleep With One Eye Open” (recorded with Scruggs in the 1950’s) and his earlier work with Bill Monroe on tunes like “Shine Hallelujah Shine”. “There was a real soulful feeling to the Flatt and Scruggs band back then,” smiles Tony, “with Paul Warren, Uncle Josh (Buck Graves), and Jake Tullock. That is bluegrass music—that’s what it is. That’s the red-hot stuff.

“And then there’s the Bill Monroe/Del McCoury duets. To this day I really love to hear Del McCoury sing and play rhythm guitar. On the sweet side, my favorite would be Bobby Osborne; the Osborne Brothers have always fascinated me as far as technical music harmony.

“If you took a survey of parking lot pickers, and even professional bluegrass musicians,” Tony suggests, “and if you asked how many have really listened to the old recordings of Bill Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs all playing together—I bet you’d find more of them haven’t heard that stuff than have. They ought to just take time and find recordings of that stuff—ignore the sound quality—and just listen to the music.”

Tony also admires a number of modern singers. These include James Taylor, Roberta Flack, Nancy Wilson, Dionne Warwick and the Seldom Scene’s, John Starling.

Striking as Tony’s vocal work had become, his guitar playing attracted even more attention. He had been a very good guitar player with the Bluegrass Alliance. Now he was in a class by himself; he had mastered a rich, varied and difficult style that was indisputably his own.

Tony’s lead work was now strong and confident. His technical mastery had increased to the point where he appeared comfortable anywhere on the neck of the guitar. He blended conventional flatpicking technique with crosspicking and with harmonic intervals taken from jazz. His sense of timing was superb and his use of syncopation had become brilliantly original. Tony’s strong musical sense kept his playing inventive, exciting and, above all, totally in touch with the feeling of whatever song he played.

“I had wanted to do my own sort of thing,” Tony explains. “I had my ideas and wanted to apply them to guitar. For a long time they were unsuccessful in that I couldn’t project them. I couldn’t bring the instrument out. Eventually I learned to do that.”

Three solo albums which are currently available showcase Tony’s music: “Tony Rice” (King Bluegrass 529), “California Autumn” (Rebel 1549) and, most recently, “Tony Rice” (Rounder 0085). On the first two he is backed by members of the Crowe band, while the last features members of the David Grisman Quintet (with which Tony now performs), fiddler Richard Greene, and also members of the New South.

Other bluegrass albums on which Tony’s playing can be heard include: Larry Rice, “Mr. Poverty” (King Bluegrass 543) Bill Keith, “Something Auld Something New (Grass)” (Rounder RB-1) and “The David Grisman Rounder Album” (Rounder 0069). He also appears on upcoming Rounder releases by Richard Greene, Tony Trischka, and Jerry Douglas.

In addition, Starday Records has recently brought out an album recorded by J. D. Crowe (with Tony and Larry Rice and Bobby Slone) in 1973. Titled “J.D. Crowe and the New South” (Starday SLP-489) the album features a bluegrass nucleus augmented by pedal steel, piano, and drums. While perhaps less polished over-all than the later Rounder New South album, there are numerous excellent performances. The record is of particular interest as it marks an intermediate, though vital and creative, point in Tony’s (as well as the New South’s) musical evolution.

In September 1975 Tony left J. D. Crowe and returned to California where he joined the David Grisman Quintet. Although the group uses conventional bluegrass instruments minus banjo (guitar, mandolin, fiddle, bass) its music—which is wholly instrumental—has more of a jazz orientation.

Nevertheless, a goodly number of bluegrass aficionados—especially those with progressive tastes—find it highly exciting. There is a familiarity in the sound of the instruments and the surprise and delight of hearing them used in new ways. The material is largely original, the group is superbly tight, and the musicians (David Grisman, mandolin; Darol Anger, violin; Todd Phillips, mandolin; Bill Amatneek, bass; and Tony on guitar) are each exceptional. Their music is, in Tony’s words: “Orchestrated music-a robust full sound. To hear it you’d never know it was me playing guitar.”

Work with the Quintet brings Tony closer to the medium of many jazz musicians he has admired and listened closely to for many years.

“My favorite guitarist without a doubt is George Benson,” asserts Tony. “I especially like the stuff he did when he was being produced by Creed Taylor on the CTI label. This was back when he was known chiefly as a jazz guitarist rather than a pop performer. He’s being overproduced now and they’re not letting him do what he really can do.”

Tony also lists among his favorite instrumentalists bassist Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen, pianist Oscar Peterson and guitarists Kenny Burrell, Django Reinhardt, Phillip Catherine and Joe Pass.Although Tony’s understanding of jazz has grown steadily over the years, in 1973 his musical insights took one jump that he remembers particularly. “I heard a jazz album by a violinist named Jean-Luc Ponty called “Sunday Walk” and it’s called “free form jazz.” The theory behind it all is: Why can’t a musician in a solo spot play what he wants to play regardless of whether it’s within the realm of the scale or not? And I’ve started doing some of it.

“There’s a bass player on that album who is my favorite musician of all time, Neils-Henning Orsted Pedersen. He’s a Danish musician who plays acoustical bass like most people can’t even play notes on a guitar.”

The Grisman Quintet has not performed extensively nationwide. It has mainly played locally in California and also has a successful Japanese tour to its credit. Although it plans to perform more widely in the future, as of this writing its music is most accessible via its excellent album “The David Grisman Quintet” (Kaleidoscope F5). The playing is flawless all around and Tony is in fine form, providing—as in his previous bluegrass work—inventive rhythm guitar and more than his share of inspired lead playing.

All in all, Tony’s career has been remarkable for a twenty-six year old migrant guitar picker. Those old Flatt and Scruggs 78’s started him on a most unlikely journey that will doubtless inspire young pickers and singers for many years to come.