Home > Articles > The Archives > The Serious Side of Roni Stoneman

The Serious Side of Roni Stoneman

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1990, Volume 24, Number 12

One of the most cherished traditions in country and bluegrass music is that of the performing family group. In addition to numerous brother and sister acts we have had the Carter Family, the Pickard Family, the Phipps Family, the McLain Family, the Lewis Family, the Whites and the Stonemans. With a history of involvement in commercial country music that goes back to the early 1920s, the Stoneman Family has been recognized by the Country Music Association as “the longest continuous act in Country Music.”

Ernest V. Stoneman, founding patriarch of the Stoneman Family act, was born on May 25, 1893 in Carroll County, Virginia. Heir to a long line of musicians, the elder Stoneman, who is remembered by family and fans as “Pop,” early in life learned to participate in the downhome singing and picking that was an integral part of the lives of his family and neighbors. By the time he was in his teens he was an accomplished performer on such instruments as the harmonica, jewsharp, banjo and Autoharp.

When he discovered that his kind of music was in demand by makers of phonograph records, Pop Stoneman made himself known to talent scout Ralph Peer of Okeh records. The result was a recording contract that placed Stoneman before a recording horn in New York on September 4, 1924 for his first recording session. For the next ten years he was one of the most prolific recording artists in country music, making available to an appreciative public 78 r.p.m. records bearing such titles as “John Hardy,” “Sinking Of The Titanic,” “Hallelujah Side” and “Lonesome Road Blues.”

During his heyday as a recording artist, Stoneman traveled widely, making personal appearances with an accompanying band that included his wife, Hattie Frost Stoneman, who played fiddle and banjo. When the Stonemans’ numerous progeny (thirteen of the twenty-three children born lived to maturity) came along, they, too, learned to pick and sing and became members of the band. The best known of the performing children were Patsy (BU, March, 1989), Donna (BU, June, 1983), Jim, Van, Scotty and Roni.

The folk music resurgence of the 1950s and 1960s created a demand for the Stonemans’ kind of music and for several years they enjoyed a popularity that put them on the most prestigious stages in the country and brought widespread exposure via television and recording contracts. In 1967 the Stonemans were voted top vocal group by the Country Music Association.

After Pop’s death on June 14, 1968, Roni, Patsy, Donna, Van and Jim decided to keep the family group going (BU, June, 1980). Now over twenty years later, country music historian Ivan Tribe, who is writing a book on the Stoneman Family, is able to say that “their continued commitment to their musical heritage is unabated. As a performing family group in country music, their longevity is unequaled and their fame surpassed only by the Carters.”

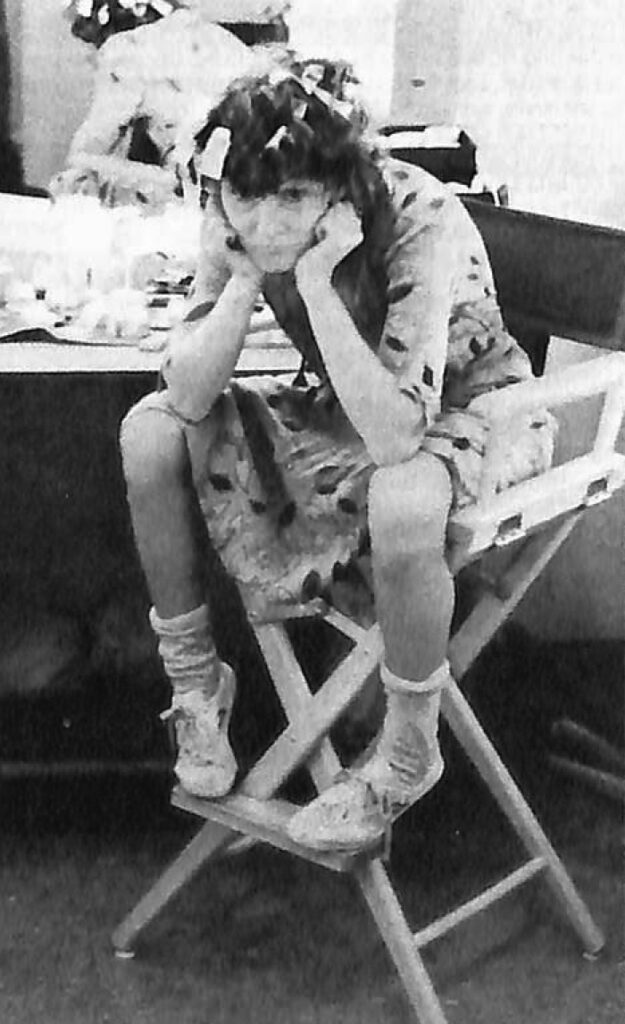

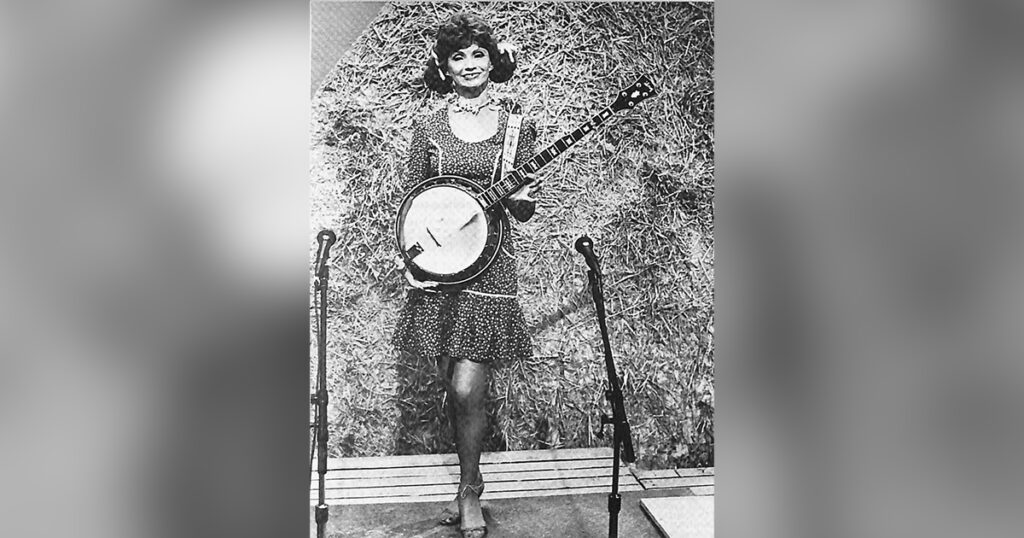

Undoubtedly the most recognizable member of the Stoneman Family is Roni (born Veronica Loretta) who, in the role of Ida Lee, has, for the past twenty years, been ironing and making menacing gestures toward her unkempt “husband” Laverne on the syndicated television show Hee Haw! Other Hee Haw! comedy roles played by Roni include Mophead, maid at the Empty Arms Hotel and the exercise lady on the segment of the show that also features the glamourous girls. Roni displays here musical talent as an accomplished banjoist when she joins forces with such other five-string virtuosos as Grandpa Jones, Roy Clark and Mike Snider.

During a recent interview in Nashville, Roni was persuaded to be serious for a couple of hours to talk about herself, her family and her career. Being serious must be no easy task for a person who once said, “I was put here on earth to make people laugh.” But Roni Stoneman does have a serious side and the interview revealed that beneath the Ida Lee exterior resides a warm, sensitive and caring person.

Roni was the seventeenth of the Stoneman children and by the time she came along, their Washington, D.C. area, home was running over with pickers and singers. “I never knew until I was in the third grade at school that there was another world besides the world of music,” she says. “I thought everyone in the whole world played an instrument and sang. I thought making music went along with breathing and walking.” When she started to school Roni says that she found it hard to identify with the family of Dick and Jane because nobody in the story-book family was carrying an instrument.

There never seemed to be enough instruments to go around in the Stoneman household and the children frequently fought over them as other children might fight over a doll or wagon. Roni says, “I remember one time Scott saying, ‘I’m going to lay this banjo down for five minutes and don’t you touch it.’ So while he was gone, I grabbed it and started playing. When Scott came back I didn’t want to give it up, because I was just getting hot—I was on a roll. And we started fussing over it.

“Later Daddy came in one evening with pieces of a banjo that he had carved out at work. He said, ‘Well, dad blame it, Roni,’—he never cussed in his life, but he would say ‘dad blame it’—I carved you out the neck of a banjo today, since you fought so much over the other one the other night.’” After Pop put the pieces of the instrument together Roni had her first banjo.

“We were never told to play an instrument,” Roni says, “But if we seemed interested, Daddy would make us one.” Roni’s interest in the banjo was inspired by a story she heard from her grandfather. “My grandfather Frost told a story many years ago when I was a little girl. He said that once when there was a fair at the Galax Fairground in Galax, Virginia, a young lady came with her mother and father from Saddle Mountain. She was sitting on the back of a covered wagon picking a banjo and he followed that wagon for miles to hear her play. Well I loved my grandfather Frost very much and he loved me in spite of myself. And I wondered if it would please him if I learned to play the banjo like that young lady. But I never could learn to play the clawhammer style.

“Earl Scruggs had a great bearing on my banjo style. He played so plain and so smooth. You could hear each note.” Roni first learned about Scruggs from her brother Scott. “One day he came home and said, ‘I heard a guy named Scruggs play the banjo and Roni, he’s wonderful. I’m going to watch his fingers. I’m going to learn everything he does and I’m going to teach it to you.’ I said, ‘Well, Scotty, maybe I won’t be able to.’ And he grabbed me and said, ‘Don’t you ever say you won’t be able to. Just because you’re a girl don’t make you stupid. You’ve got hands and fingers just like a man and you’re going to play like a man.’”

Roni may have learned to play the banjo like a man, but she has been called the “Queen of the Five-String Banjo.” Being able to play like a man was not of much help when she decided to go against a man in a banjo-picking contest. “I was playing in a banjo contest up in Pennsylvania,” Roni relates. “The first prize was a new Vega banjo and I needed one so bad.” The competition was soon narrowed down to two people’ Roni and a man from New York. “So the judges called me in,” Roni says, “and they said, ‘We can’t give you the banjo for first prize. You’re a girl and shouldn’t win first prize.’” She had to settle for second place.

Today Roni plays a 1950s Gibson Mastertone arched top banjo that she bought in a music store in Baltimore, Maryland. “It still has the same plastic head it came with,” Roni says. “It has so much dirt on it. The other day I got a cloth and tried to clean it up, but I was afraid to get it too clean. I was afraid it would lose its soul. This is not just a banjo—this is a war horse to stand what I’ve put it through. I don’t take care of it properly,” she explains as she shows how the back is worn from having been dragged across countless stages when she says she was so tired she could hardly stand up and play, much less carry a heavy banjo when she didn’t have to.

One of Roni’s earliest recollections of performing in public was when the family entered a band contest in Washington, D.C. “One day Daddy came home,” Roni recalls “and said, ‘Hattie, they’re having a contest at Constitution Hall with Connie B. Gay and we’re going to take all the kids and go up there and get in that contest and see if we can win.’” The winning band would be awarded a television contract. “So Daddy went across the creek to talk to my older brothers, who had moved out of the house, about entering the contest. But by this time they had gotten away from Daddy’s old-timey music and had bought electrical instruments. When he came back he said, ‘Well, Hattie, the boys ain’t going with me. They say that I’m outdated. They said that my music is too old-fashioned and I won’t win.’ My mother said, ‘Ernest, the only thing I know to do is get my fiddle in tune and I’ll go. We’ll take the little ones with us and we’ll go.’ Mama made me and Donna feed-sack dresses and we went to Constitution Hall and won the contest. And we were on the Connie B. Gay television show for 62 weeks.”

Roni also remembers the family’s performing on radio when she was a child. “We were on this little radio station out in the middle of the boonies, but we liked it because we got to pick and grin. They would stand us kids up on soft-drink crates so we could reach the microphone. I knew there were a lot of old people listening to us. So this one particular day we were all out at the radio station. Everybody got to sing their song and I said, ‘I’ve got a song to sing.’ Daddy said, ‘All right, it’s Roni’s turn to sing.’ I said, ‘I want to do a song for all the shut-ins called ‘Little Rosewood Casket.’” I sang that song with all the gusto of an eight-year-old.” Pop Stoneman thought Roni’s choice of song was inappropriate for dedicating to shut-ins and when they went off the air he let her know with that device all too familiar to the Stoneman children, the hickory switch. Through an oversight the door between the studio and the room where the punishment took place was left open and the radio audience became privy to a Stoneman family domestic crisis. “And the phone started ringing,” Roni says. “‘Don’t whip that girl,’ the listeners were calling in.”

Pop Stoneman had a hard time accepting Roni’s antics. “I was not a mean kid,” says Roni. “I never was a liar. I never stole anything. I was just squirrelly or something. Different. But Daddy didn’t like my humor.” Roni says that it was Mac Wiseman who convinced her father that he should leave her alone and let her be a comedienne. “We were playing Las Vegas. The Stoneman Family was backing up Mac Wiseman. Mac was singing these serious songs and I was cutting up. He sang a song about ‘my canoe is under water now’ and I would go ‘gurgle, gurgle, gurgle,’ into my microphone. Then he sang a song about ‘my banjo is unstrung’ and I would go ‘Bong! Bong!’ After we got off the stage Daddy was yelling at me in the dressing room. Mac came in and says, ‘Pop, she didn’t bother me. Just let her alone. People love her. They like for her to do things like that. Let her have fun and let the people have fun with her.’ And after that, Daddy left me alone.”

Roni landed her job on Hee Haw! because of her favorite movie actress. “Marjorie Main, who played Ma Kettle, was my favorite actress when I was growing up,” she explains. “Most girls my age liked Esther Williams and glamorous stars like that. But I liked Marjorie Main because she reminded me of the Stonemans. I learned to talk like Marjorie Main. I learned every inflection of her voice. When I used to play in bars in Washington, D.C., with Scotty I would use that voice to keep the drunks from fighting. It would make them laugh. When the people at Hee Haw! called me in to read for the Ida Lee part they said that they needed a skinny Marjorie Main. And I said, ‘Shoot fire. I’ve got that.’ When they heard me they said, ‘That’s just what we want.’ So I’ve been doing the Ida Lee part ever since.”

The leading role in a domestic scene is an appropriate one for Roni Stoneman for she is a domestic person. “I’m a home person,” she confesses. “Isn’t that strange? I like planting flowers. I clean the yard. I can paint and fix things. I like to go down the street and talk to neighbors and have coffee with them. I like friends.

“People are like an upper to me. A natural upper. I love them. I really do and it has nothing to do with picking and grinning. It comes from somewhere. I don’t know where.”

Roni also loves bluegrass music. “I love bluegrass music because it makes me feel real good deep down in my soul,” she once told writer Don Rhodes (BU, May, 1977). “It gives me such a warm glow. It makes me feel like someone has given me a good, warm toddy.

“Bluegrass music is my heritage, of course,” she said in a later interview, “but we didn’t call it bluegrass. Bill Monroe gave the music its name because he’s from the Blue Grass state. But my grandfather and my great grandfather all picked the same instruments and did the songs that they do now.”

Roni’s commitment to bluegrass music is not just in word only. She has recently started performing with the family again. She is prominently featured on the Stonemans recent all gospel album titled “Family Bible.” In this, the family’s first all-gospel album. Roni sings two songs, “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” and “In The Garden,” allowing listeners a chance to hear her in a role not often heard. She also contributed an original verse for “Will The Circle Be Unbroken,” revealing yet another of her talents.

Roni also has her own bluegrass band called Formal Grass. The Stoneman Family and Formal Grass perform at bluegrass festivals and other musical events.

As a performer Roni Stoneman owes a lot to her brother and her parents. From them she learned that only a job well done deserves a reward. When she started playing the Washington-area honky tonks with Scotty, he told her, “You’ve got to learn how to do it right, or you don’t deserve to get paid.” Roni also recalls the words of her father: “If you can’t play it right and you can’t entertain them folks out there, I don’t care if you are our brother, sister, or aunt, or grandmother, you don’t belong on the stage.” Today when Roni Stoneman goes on stage or before the television cameras, she does so with, as she says, one thought: “Those people out there have got to be thoroughly entertained with every bit of your being.” That’s the serious side of Roni Stoneman.

Share this article

6 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

So very inspiring to a fellow banjo player who liked Hee Haw! in my teens and lived in D.C.!

What a wonderful article, it brought back so many memories. I used to hear the Stoneman’s in local D.C. bars, when I was in my “Beer Joint” phase of life. I’m 95 now, and bluegrass is my main joy in life, well I kinda like food too. Thanks you for keeping bluegrass on the front burner, as it is all we have left of country music.

John Collins and I had a great time at roni Stonemans home.she and Bill and Barbra fixed dinner for us great hamburgers. We talked for hours on end,I have pictures and videos of it it shook me to the core to get the information of her passing. Loved your story ❤️.

Roni and I were really good buddies. She always recognized me from the stage if she saw me in the audience. We sat and jammed many times when we both would be at the same show. I gave her a really small thumb pick once and in turn she gave me the pick she had used for several years. It had grooves inside that Pop had cut with his knife so it would not slip off her thumb.

RONI was special I meet her in lancaster pa about 10 years ago . At American music theater.after the show I asked her to autograph my eppiphone banjo.i said it was a cheap banjo and she said honey this is a good banjo and she started playing it .it sounded like a good banjo . I have photos of her playing it .she also kissed me on the cheek. My wife and I talked her for a good while. I am really sorry to here Roni passed but I know she playing the banjo for the lord now.

Excellent article. I remember watching the Stoneman’s as a young boy growing in in Mt. Juliet, Tennessee and Una, Tennessee. Ronnie was always my favorite. I could not wait for her, Homer and Jethro and Rowlf from the Jimmy Dean show to come on. Funny and just as good a banjo picker as Earl Scruggs, maybe better.