Home > Articles > The Archives > The Road of Columbus: Beppe Gambetta Conquers A New World

The Road of Columbus: Beppe Gambetta Conquers A New World

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1995, Volume 29, Number 8

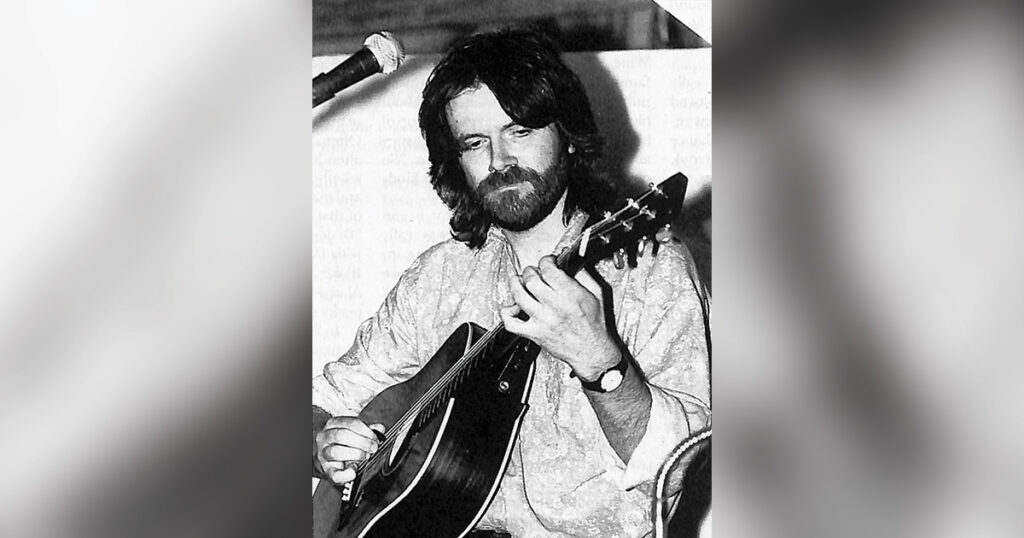

Its late; sometime after 2 a.m., and a charismatic guitarist with a gap-toothed grin and a full shock of reddish-brown hair and beard still performs for the cheering crowd clustered around the crude stage wedged among the campsites at the Walnut Valley Festival.

Of the thousands of flatpicking guitarists who make the annual pilgrimage to Winfield, Kans., every year for the National Flatpicking Guitar Championships, none has come farther than the man on the stage this night. Finishing his set, he smiles and bows to his fans and says goodbye to his new friends in his native language, “Ciao,” before disappearing into the campgrounds.

For Beppe Gambetta, an Italian musician as fiercely devoted to bluegrass and flatpicking guitar as any musician born in Tennessee, Kentucky, or any other American hotbed of bluegrass enthusiasm, devoting his life to touring and performing has made him a citizen of a larger world.

“In a way, I no longer feel like I am Italian,” Gambetta explains in a voice colored with Old World inflection. “I began at first to leave Italy because I couldn’t find enough jobs performing. But then, if you begin to be on the road and you come into contact with these other cultures, you cannot give up to think about meeting your picking friends in Germany or Czechoslovakia or Winfield, Kans., because a little bit of your heart is there. It’s really strange; the more you develop this sensibility, the more you feel that the bluegrass community is your home.”

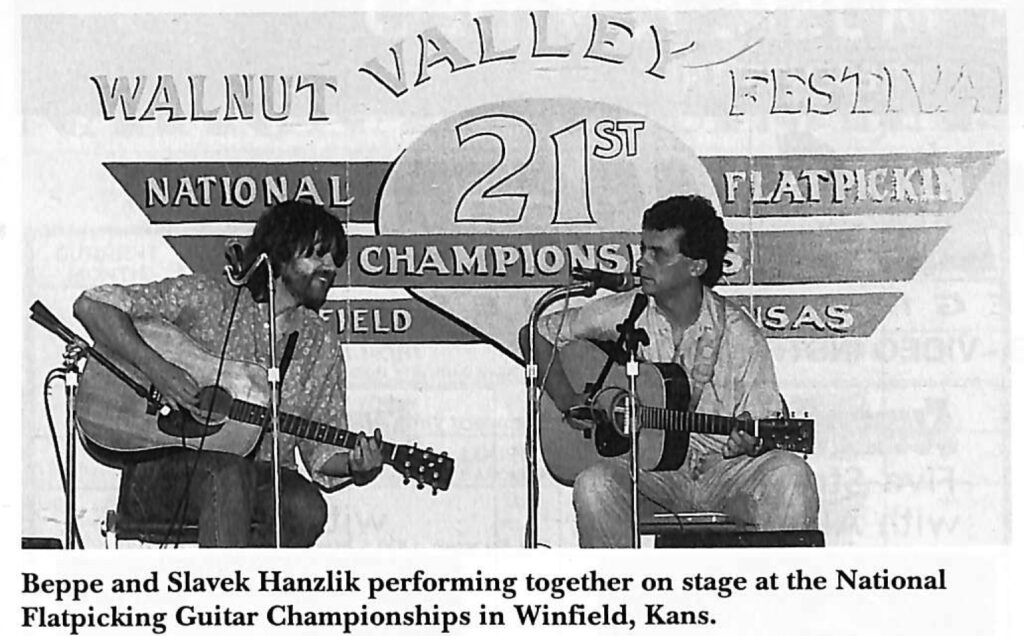

Increasingly, foreign bluegrass performers are finding new homes on this side of the Atlantic, where enthusiastic fans appreciate great musicianship and an abiding love of blue grass wherever it originates. Along with friend and fellow flatpicker Slavek Hanzlik of Czechoslovakia, Beppe Gambetta brings to guitar a new sound drawing on American and European musical traditions. The emerging hybrid, as the hundreds of fans crowding around the tiny Stage 5 at Winfield have discovered, gives instrumental bluegrass another promising, exciting new direction.

For someone who’s now pushing back both technical and stylistic barriers on his instrument, Gambetta’s introduction to bluegrass guitar flatpicking couldn’t have been any more traditional. Like so many American musicians, Gambetta heard Doc Watson play “Black Mountain Rag” and decided on the spot he had to explore this compelling, utterly foreign style of guitar.

Already familiar with guitar, Gambetta began searching out more bluegrass, a difficult task in Italy 20 years ago. Just finding records, he recalls, “was really, really hard; just one or two shops in the whole of Italy were having some records, and they were really, really expensive.” That isolation, Gambetta now realizes, made his experience with bluegrass similar to what the early bluegrass enthusiasts must have endured.

“We couldn’t see people playing bluegrass music, so we reconstructed the approach that a lot of (American) people had on Saturday night when the radio was playing bluegrass music and a lot of people learned to play bluegrass just by listening to the radio. We were just listening to the records and we could see nothing of how it was being played; just guessing what was happening. And we had the strong problem of the language to overcome,” Gambetta explains. So strong was his fascination with bluegrass and flatpicking guitar that he’d stare at photos of Doc Watson, Clarence White and other players trying to determine how they were playing a chord or holding the flatpick.

One slight advantage he did have came from living in Genoa, a major Italian port city best known as the birthplace of Christopher Columbus. Unlike many other regions of Europe where one could find maybe just one or two bluegrass musicians, Gambetta fortunately found three equally talented, dedicated bluegrass musicians there and formed Italy’s first bluegrass band, Red Wine.

“We made it because we were really lucky to find four people who loved bluegrass music,” he recalls. “It was really our main love.” Spurred by the chance to perform professionally with the band, Gambetta began playing more gigs, occasionally traveling to other parts of Europe to play. But much like the experience of many fledgling American bluegrass bands, Red Wine struggled to develop an audience for its music.

“When you’re exposed to a public that isn’t prepared for bluegrass, it’s always the same long, hard fight. But with the band, we learned to present it in a better way. If there is a good thing that you have never eaten, if you put some nice familiar things with it, you will like it better,” Gambetta explains. To win over curious European audiences unfamiliar with the sound and tradition of bluegrass, Red Wine would incorporate other, more familiar musical elements. “And in every public, even if they know nothing about bluegrass, there will always be a group of bluegrass fans: they just don’t know they are bluegrass fans yet,” he laughs. “So our goal is always to discover these kinds of people.”

Eventually, that philosophy began paying dividends. “Red Wine was really accepted around Europe. We were invited to so many good festivals and we got to meet so many of the good players,” he explains. A highpoint for the band came when it was invited to one of Europe’s biggest and most important bluegrass festivals in Toulouse, France. “The first time Red Wine played there was the year when New Grass Revival did their live album there,” he notes.

Despite some success, however, opportunities to perform professionally remained scarce in Europe. Like the other members of Red Wine, Gambetta had a day job as a social worker and none of the band members could afford to give up their jobs to make a living playing bluegrass. Personal trauma, Gambetta says, helped him make the difficult decision to abandon the security of not just his job but his home country to adopt the vagabond ways of the international touring professional.

“It was a sad moment of my life because I was getting into my divorce, a divorce with a lot of troubles, and I was really suffering a lot. I was the person that needed to change my life a little bit, and I realized that I was giving up being a full-time musician so many times because of my family, and now I was alone. So this was the opportunity,” he says. Like so many other hopeful young players, Gambetta gave himself a year to see how his musical career would develop. “And after a year, yes, I see it begins to work, so let’s give it another year and another and so on and so on,” he explains happily, smiling at the thought of the many tough dmes he’s endured and overcome.

Buoyed by his success, Gambetta worked up his nerve and followed the same road fellow Genoa native Columbus pioneered 500 years earlier. He arrived in America carrying his guitar, a few belongings and a portable digital tape recorder, and began pursuing a dream. Armed with only about 20 words of English and unable to even read the destination signs to find which bus he needed to get on, Gambetta began traveling across the country, meeting as many of his American musical idols as possible. Often, he’d show up on their doorstep after just a brief, nearly unintelligible telephone call asking if he could come and make a record with them. The result of that cross-country musical odyssey is “Dialogs,” an instrumental CD of duets with David Grier, Dan Crary, Norman Blake, Mike Marshall, Jon Jorgenson, Alan Munde, and other top bluegrass performers.

“In 20 days, I learned a lot of English. I learned because I was desperate,” he says with his trademark boyish grin. “I got to meet these musicians—I touched the hand of Doc—but it was a suffering because I didn’t speak English. I felt the strong energy of these people to play perfectly note-for-note, and I couldn’t communicate with them.” Like all music, though, bluegrass speaks a universal language and the resulting album reveals Gambetta’s remarkable talent for communicating with his guitar.

That trip, followed by regular visits to play for American audiences, resulted in lasting professional relationships with Tony Trischka and Dan Crary, both of whom have returned the favor and toured Europe with Gambetta to help spread American bluegrass to new audiences. For American musicians, Gambetta says, it’s hard to imagine how potent a social and political force bluegrass music has become overseas.

“If a person loves bluegrass, even if he can find nothing, he is going on. An example is Czechoslovakia in the ’70s. They had to sing bluegrass in Czech because it was forbidden to speak in English. A friend of mine was writing two letters to Tony Trischka, and after writing these two letters to America the political police break into his house and ask him why is writing to America. So it was tough. That’s probably why bluegrass is so strong in Czechoslovakia, because it is related to liberty and freedom Gambetta relates. Going to American-style bluegrass festivals was one of the few opportunities for young Czech people to gather under the old Communist regime where they could speak openly about freedom and democracy.

“In the U.S., they don’t realize too much that bluegrass music is a meeting point for many people outside the United States” he insists. “This aspect is really important to realize; the folk music is putting together more people, especially bluegrass. I have great friends in Czechoslovakia, and in Korea and Australia because of this music.”

On one journey, Gambetta played only 20 miles from the former Soviet republic of Ukraine. After asking the border guards if they could enter the Soviet Union just to play one tune there, a crowd of 600 fans and about 25 banjo players turned out to hear Gambetta and Trischka play.

But it’s not just audiences in bluegrass-starved foreign destinations turning out to hear Gambetta’s creative, highly melodic form of flatpicking. He’s been drawing glowing reviews and strong crowd reaction here as well, leading to frequent appearances at U.S. festivals such as Winfield, Owensboro, and the Merle Watson Memorial Festival and solo performances around the country.

Naturally, Gambetta enjoys and appreciates the respect and popularity he’s earning here. As a musician alternating between two very different cultures, he sees distinct differences in the way European and American audiences react. And he says the novelty of coming horn Italy to play bluegrass for American audiences even offers some advantages professionally.

“I generally like the American mentality of going and seeing a show. Americans relate to a show in an intense way,” he believes. “American people are able to enjoy a show better than many other cultures. I probably don’t have enough English to say this, but (American) people are born to enjoy a show as one of the things they have inside. It is a sort of hospitality. They forgive me if I make little mistakes. So from that point of view, it probably helps (me) being foreign.”

Gambetta’s sense of breaking down cultural barriers now directs his professional goals. As a musician, he’s taken influences from Norman Blake, Dan Crary, Doc Watson, and Clarence White to develop a liquid, flowing style of guitar driven not by flashy technique but by respect for the melody. In concert, his charming accent and naturally outgoing personality make him extremely popular with audiences. It’s evident that Beppe Gambetta loves the music he plays and couldn’t be happier that he can earn his living playing guitar for bluegrass fans around the globe.

As a growing, maturing musician, he’s now incorporating his own ideas and influences into his unique style of solo flatpicking guitar. “I am breaking boundaries. The basic music that I love, the whole of my career, is of course bluegrass and flatpicking. But when I start to compose, that is something you cannot control. It conies from your heart and all these different influences come out,” he relates. “The concept is to try to explore with good taste a little bit beyond the borders of flatpicking music. The danger is I am listening to so much music that is folk music from other countries that it comes inside in my playing. But I think people understand this, even if I am playing something with a Slavic scale inside it because they enjoy that at the bottom is the big love for this bluegrass music.”

Most recently Beppe has signed with Green Linnet Records. His new CD “Good News From Home” is due for release this month. He will also be doing instruction tapes this summer for Homespun Tapes.

David McCarty is a staff writer for BLUEGRASS UNLIMITED who’s played bluegrass and other acoustic music for more than 20 years. He writes regularly for this and other national music, magazines.