Home > Articles > The Archives > The Return of Donna Stoneman—First Lady of the Mandolin

The Return of Donna Stoneman—First Lady of the Mandolin

Re-printed from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June, 1983, Volume 17, Number 12

Back in 1971, Bluegrass Unlimited conducted a poll asking readers to list their favorites among pickers of standard bluegrass instruments plus lead, and tenor vocalists. Significantly, when the results were announced that December, all but one who placed in the top ten in each category were men. The one exception to this exclusively male compilation ranked among the top mandolin pickers, but probably took little consolation in it at the time since she left the world of professional music soon afterward. For a decade, Donna Stoneman, the principal subject of this sketch, found a new happiness in the service of God. Fortunately for Donna and others as well, she is retaining this mission, but has also recently resumed public performing with the Stoneman Family.

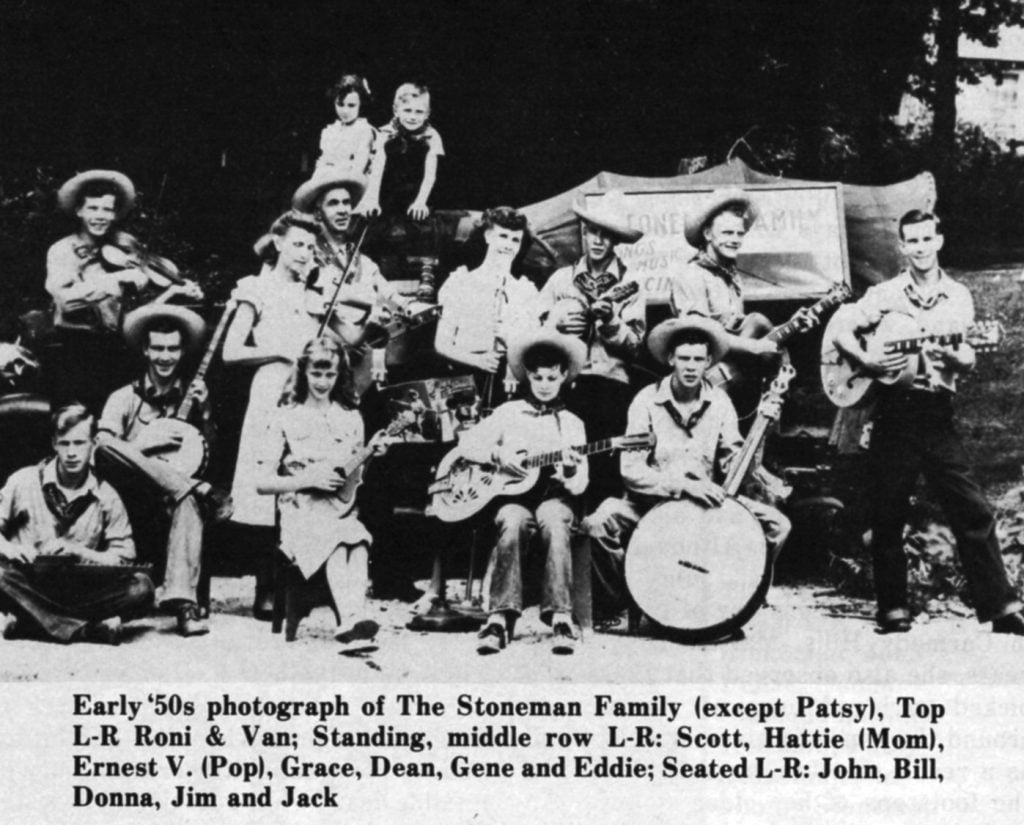

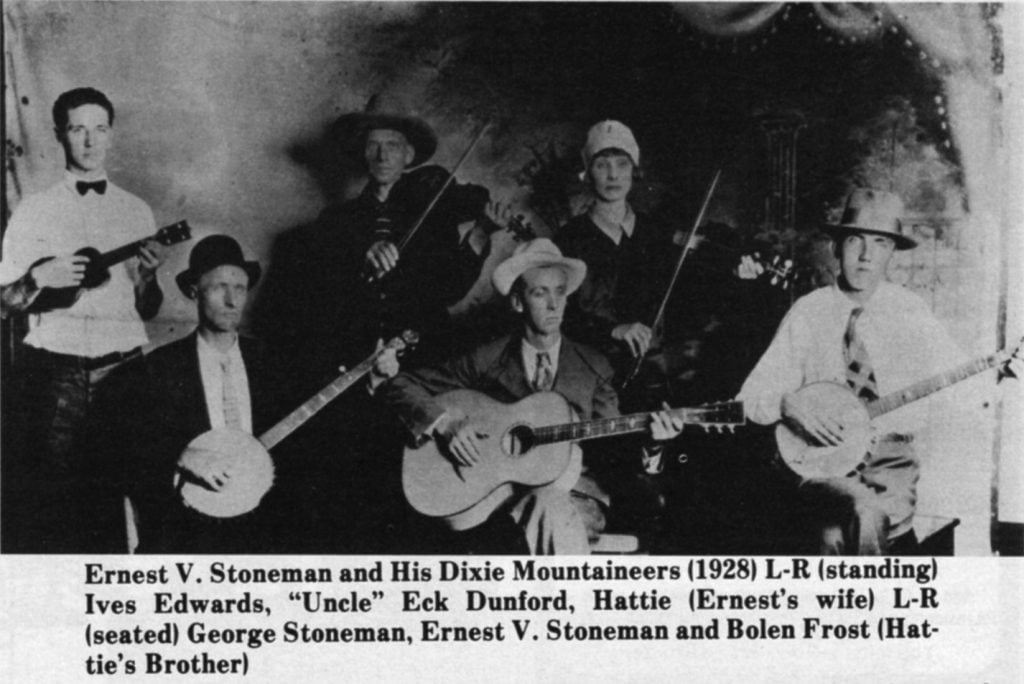

The family, of course, has a history of professionalism and recording their brand of music that goes back six decades. Ernest V. Stoneman, patriarch of the clan, had been born on May 25, 1893, at Monarat, Carroll County, Virginia. In 1919, he married Hattie Frost and 1921 saw the birth of the first child Eddie. Over the next couple of decades, Ernest and Hattie would have twenty-two additional children, fifteen of whom survived infancy.

In 1924, Ernest Stoneman began a recording career that would take him northward from his Virginia home many times. Between 1924 and 1934, he journeyed to the studios of such phonograph record labels as Okeh, Edison, Gennett, Paramount, Pathe, Vocalion, and especially Victor. In addition to self-accompanied ballads with guitar and autoharp, his sessions contained those musicians who brought the so-called “Galax sound” to its best such as Eck Dunford, Bolen and Irma Frost, Kahle Brewer, Frank and Oscar Jenkins, Fields Ward, George Stoneman, and Willie Stoneman. Hattie Stoneman also participated in some of the recordings and on his final (until 1957) studio visit in January 1934, Eddie Stoneman played accompaniment and sang harmony with his Dad.

Whether recording solo or with a larger band, songs in the Ernest Stoneman repertory that later entered into the ranks of bluegrass “evergreens” are numerous. A few include such standards as “Nine Pound Hammer,” “John Hardy,” “Wild Bill Jones,” “Watermelon On the Vine,” “Katy Cline,” “Little Old Log Cabin In the Lane,” “New River Train,” and many instrumentals. Stoneman’s 192 issued sides divided about evenly between songs introduced to records by him and those of which he did “covers” at his recording company’s request. In fact, some of his best compositions like “The Poor Tramp” and “When the Snowflakes Fall Again” have for some reason become almost exclusively in the preserve of the Stoneman Family.

In the meantime, Ernest, Hattie, and the children moved from their home near Galax to metropolitan Washington, D.C. where radio offered another commercial opportunity for the increasingly popular, professional, and prosperous country musicians. However, a symbolic dark cloud soon appeared on the horizon that would become known as the Great Depression and hover over the American scene for a decade. Despite all of Pop Stoneman’s talents as musician and carpenter, few work opportunities existed in either field or any other for that matter. Patsy, who has some childhood recollections of the good years, recalls that the Stoneman’s hit bottom about 1931 and remained there until the coming of World War II. A series of one-room shacks served as home for a family that kept increasing in size during the decade. “Prayers and pinto beans” sustained the family during this period although at times amounts of the latter tended to be insufficient. Eddie Stoneman recalled in 1979 that he and his dad got a radio show on WJSV for several months in 1937 as the duo of “Ernie and Eddie,” but their popularity led to dismissal because it stirred excessive jealously from other acts. About 1938, a newspaper story reported that Patsy passed out in a school room from hunger and she remembers that Pop sometimes went as long as three days without food. About 1940, Pop bought a lot and in 1941 built a house (of one room) in Carmody Hills, Maryland, where the kids slept. He and Mom slept in a half-dug basement and a huge piece of canvas sufficed as a roof for two years until he could afford better.

Donna LaVerne Stoneman, the tenth of the surviving children, hadn’t yet arrived when Pop had his final prewar recording session. Although born in Alexandria, Virginia, some of her earliest recollections are of the cottage in Carmody Hills, Maryland. In those years, she also observed that those who picked stringed musical instruments around the house received attention and as a result she, too, began following in the footsteps of her older siblings. An early interest in the banjo waned quickly because of its weight, while the lightness of the mandolin placed no restrictions on her movements. She also developed a pair of the “dancing-est” feet one could imagine and harbored secret ambitions to be a dancer. Another vivid childhood memory of Donna’s resulted from a summer visit to her grandparents back in southern Virginia when she had an extremely close call with serious injury or possible death while rescuing little sister Veronica from the charge of a mad heifer. She attributes their narrow escape as an early manifestation of the hand of God in her life.

The coming of World War II brought an end to the dire poverty the Stonemans had endured in the 1930s. Pop and Eddie found increasingly steady work with Pop securing regular employment at the U.S. Naval Gun Factory. A roof replaced the canvas shelter and a front porch provided a little elbow space in their crowded cottage. Shows at military camps provided expanding opportunities. Donna improved her playing skills through this period. In the early years she recalls breaking a lot of strings and Pop sometimes had his doubts as to her musical prowess. Finally, Scotty who’d provided encouragement suggested to Pop that he let her “play like a man” apparently intimating that earlier the family elders attempted to steer her toward the soft type of instrumentation generally associated with popular females of that era like the Girls of the Golden West. She altered her style a bit and eventually broke fewer strings.

In the years after World War II, Pop continued work at the Gun Factory, but plenty of club activity kept him musically busy, too. Patsy recalls that there might be three or four bands made up largely of Stonemans functioning at the same time playing a variety of clubs. Such groups bore names like Pop Stoneman and his Pebbles (built around the youngest children Veronica and Van and two neighboring kids Zeke Dawson and Larry King), the Stoneman Brothers (Bill, Jack, Eddie, and sometimes Dean and Gene), and most important, the Bluegrass Champs. Patsy worked primarily as a single and pleasantly recollects lots of playing with such noted bluegrassers as Bill Emerson and Bill and Wayne Yates among others.

The younger children performed relatively early in the evening and older ones would play in the later hours. Hardly an ideal environment for growing children, Pop, a stern disciplinarian, kept things in line most of the time. Even then, worldly temptations presented occasional problems for some family members, most notably Scotty. Donna, however, avoided the bad habits often associated with club work. In 1978, she told an interviewer that she had asked God for help in avoiding alcohol and tobacco at this early date. Although this preceded her conversion by many years, apparently He answered her prayers as she has remained a total abstainer to this day.

An upward musical advance for the Stoneman Family came about 1947 when they won a talent contest at Constitution Hall, one of Washington’s premier auditoriums, that led to appearances on television. Later they appeared on “Town and Country Time,” one of the early Connie B. Gay productions in the Washington area. This provided the family with exposure to the widest audience since the days of Pop’s radio programs and records. They also did radio work at WARL Arlington, Virginia.

From that time on, the Stonemans received more media attention, but still did almost all of their playing in the greater Washington area. Donna, who claims only a seventh grade education, became a full-time performer from the age of sixteen. At eighteen she obtained the Gibson F-5 mandolin which is still her favorite instrument and in recent years has played and endorsed Joe Morrell strings. Pop’s career hit another high-point about 1956 when he appeared as a contestant on the NBC network quiz program, The Big Surprise. His knowledge of geography won him some twenty thousand dollars on the Mike Wallace-hosted show and he and Mom also performed a song, too. Donna recalls that he wanted to take the children on with him, but they didn’t go.

The decade of the fifties also saw the Stonemans return to the recording studios. In 1957, Ernest Stoneman cut ten numbers for Folkways with some help from Hattie and some of the children. In 1961, he recorded six more tunes in his Carmody Hills home for Mike Seeger for an autoharp album.

Donna did not participate in any of the Folkways sessions, but had by this time become thoroughly experienced primarily with the Stoneman-dominated group known as the Bluegrass Champs. This aggregation gained their nickname from their winning the prestigious national band contest at Warrenton, Virginia where Scotty also won several national fiddle championships, his first at sixteen. They worked three nights weekly at a Washington club called the Famous for quite some time and guested on the Old Dominion Barn Dance. Membership in this band varied from time to time although Donna was always part of it. Scotty, Van, Jimmy, Roni, and Pop were often there, too, although not always.

Some other members included Dobro players Peggy Brain, Lew Houston who went by the stage name “Lew Childre” after the veteran country radio star, banjoist Porter Church, and guitarists Jimmy Case and Perry Westland. About 1956 the band played on and won the CBS network show Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts. At other times Charlie Waller, Bill Emerson, and John Duffey, then members of the newly organized Country Gentlemen, served brief stints with the Bluegrass Champs. In this period of time the Washington area had begun to emerge as the major center of creative bluegrass in the country, and bands like Buzz Busby’s Bayou Boys, Bill Harrell’s Virginians, the Country Gentlemen, and the Bluegrass Champs flourished with club work, radio, and local television. The Stonemans thrived in this musically rich environment although Donna confined her music almost totally within the family groups. Scotty ranged over a wider field, fiddling at least a little with most of the previously mentioned bands.

The Bluegrass Champs did some recording in this period. Their initial record release on the Bakersfield label “Haunted House”/“Heartaches Keep On Coming” came out in the summer of 1957. The former tune featured Scotty on fiddle and is an altogether different number from the later rock and roll hit. This release marked Donna’s debut on recordings. Another single release followed on the Blue Ridge label. “Jubilee March” spotlighted Houston’s Dobro and Donna’s mandolin playing while “Hand Me Down My Walking Cane” featured the first Ernest Stoneman vocal with bluegrass and trio vocal backing.

The Bluegrass Champs also backed vocalist Luke Gordon, initial popularizer of “Dark Hollow,” on an album and did some recording that later came out as half of an album shared with Jimmy Dean on the budget Wyncote label. It included some nice bluegrass tunes such as “Daddy Stay Home” and Scotty’s recitation “Little Tim” (later re-recorded as “Guilty”).

In 1958, the Bluegrass Champs had a regular television program on WTTG Washington, D.C. Available tapes of the audio portions of this show indicate that the Stonemans had already begun to incorporate contemporary material into their still basically traditional style. Songs like “The Story of My Life” and “Just Married” then rockabilly hits for Hall of Fame inductee the late Marty Robbins and the original Elvis Presley hit “That’s All Right” had entered the Stoneman repertory. Donna displayed some excellent mandolin work on the latter and contributed good vocal harmony and an occasional solo.

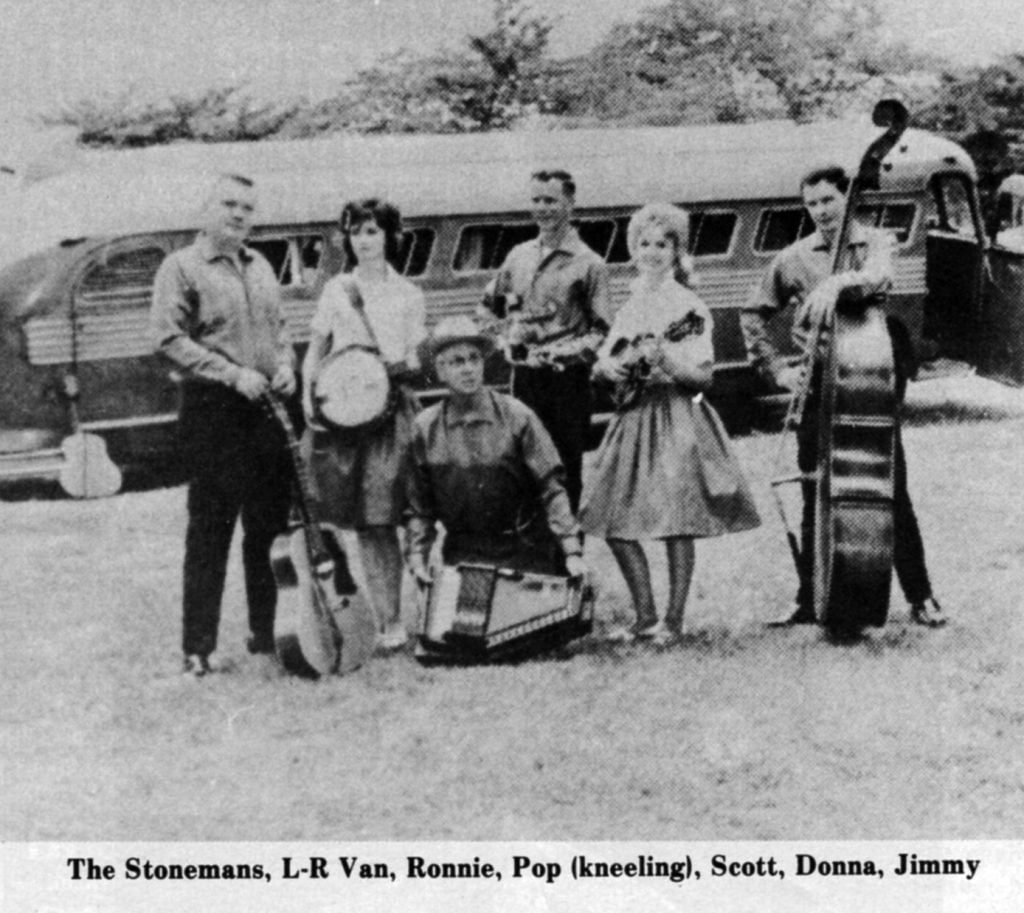

By 1962, the Bluegrass Champs had evolved into an all-Stoneman group. In addition to Donna’s mandolin and vocal harmony, Roni played banjo and performed comedy, Van did the guitar work and most lead vocals, Scotty fiddled, Pop played autoharp and also did his old-time songs, and Jimmy played an outstanding bass fiddle. Traditional music experts like Mike Seeger and Dave Freeman who saw the Stoneman Family in this period recall them as a dazzling, dynamic band who provided their audiences with superb music and showmanship.

Pop retired from his job at the Gun Factory and the band believed themselves ready to tackle Nashville which had become the center of the country music industry to a degree that it had never been in his earlier days. They secured a guest spot on the Grand Ole Opry and as Donna recalls “brought the house down.” However, instead of just doing a brief encore, the Stonemans did the whole song over and somewhat without realizing it took up about eleven minutes of another artist’s time which alienated him from further appreciation of this highly dynamic group of what the Nashville establishment considered unknowns. Donna later commented that the entire incident drove them back to the Washington area like a “whipped pup.”

Not all had gone wrong, however, as they did some recording for the Gulf Reef and Starday labels. They did a single “White Lightning”/“Sadness” for the former firm and also backed legendary Opry announcer Grant Turner on a pair of recitations. Two albums — “Bluegrass Champs” and “The Great Old Timer at the Capitol” emerged from two Don Pierce-produced sessions and a couple of cuts that appeared on mixed LPs.

Some very fine songs came out of those sessions. Perhaps most notably was Scotty’s classic rendition of “Orange Blossom Special” which they titled “Orange Blossom Breakdown” and also features a lot of Donna’s unique mandolin work as did Pop’s vocal of “When the Snowflakes Fall Again.” Donna also contributed her first recorded original mandolin number, “The Girl From Galax.” Most of the songs waxed on Starday constituted either Pop’s old-time singing or straight bluegrass. A few songs tended toward the slow sentimental type of ballad then part of the rock and roll genre. These included songs like “Out of School” and “Family Life.” Unfortunately, the two original Starday albums went out of print rather quickly, but a revamped version appeared in the later sixties titled “White Lightning” and still another one on Starday’s budget label Nashville.

Donna also made one of her rare appearances outside the family circle about this time on a recording session. In the fall of 1962, Rose Maddox waxed her Capitol bluegrass album. Don Reno played banjo; Red Smiley, rhythm guitar; John Palmer, bass; and Steve Chapman, the electric lead guitar. Bill Monroe did the mandolin work on five cuts and Donna did the other seven including “The Old Cross Road,” “I’ll Meet You In Church Sunday Morning,” and the songs not associated with Monroe such as “Each Season Changes You.” Since Donna remained hitherto unknown outside of the Washington area and among musicians generally, her presence on the session shows something of the status she possessed in the trade at the time.

The Stonemans also entered into an association with Jack Clement, a record producer, manager, songwriter, and sometimes artist at about this time. Clement had known the group from some time he himself had spent in the DC area in the early fifties. Jack suggested that the Stonemans go to California where he believed, correctly, that they could make a major impact on the folk-country-bluegrass scene and use this experience as a vehicle for gaining more respect in Nashville. Clement lived in Beaumont, Texas at the time and he also got some work for them in East Texas.

The Stonemans did indeed make a name for themselves on the West Coast. From January 1964 they secured engagements at places like the Ash Grove and The Troubadour in Los Angeles, the Monterey Folk Festival, Disneyland, and later won a big following at Fillmore West in San Francisco. During this period, Mitzi Gaynor saw the Stonemans in concert and had Donna teach her one of her dance steps. They recorded an album for World Pacific which Donna says they actually made in Beaumont, Texas with canned applause. Nonetheless, the album which ranks as excellent bluegrass manages to convey some of the excitement that the band generated on stage performances during that period of their careers although Donna contends that most of the time the Stoneman Family got much more applause with their showmanship.

For bluegrass diehards, the album probably comes closer to being the pure stuff than their later sessions. Their renditions of songs like “Little Maggie,” “Lost Ball In the High Weeds” (titled “You’ll Be a Lost Ball” on the earlier Jimmy Martin version), and “Darlin’ Cory” proved that they can handle traditional bluegrass with the best. Scotty, Roni, and Donna display their instrumental talents on tunes like “Fire On The Mountain” and “Dominique” with Donna’s tasteful and excellent mandolin work showing up especially well on the well-known composition of the “Singing Nun.”

The Stonemans (as they now became known) also got themselves some network television exposure in this period and appeared on such programs as the Steve Allen Show and a Meredith Willson Special.

In 1966, the Stonemans relocated in Nashville again. This time events moved in their direction. They had signed a contract with MGM records in December 1965 and had their first and in some respects best album released that spring. Entitled “Those Singin’ Swingin’ Stompin’ Sensational Stonemans,” it displayed their artistic versatility quite well.

Pop did a couple of lead vocals on “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” and “Message From Home Sweet Home,” a song not often heard since his own earlier recording in 1929. The old Johnny and Jack hit, “Ashes of Love,” received an excellent bluegrass treatment and the Stoneman rendition probably helped boost it into the status of a standard it has since achieved. More common bluegrass numbers included “Mule Skinner Blues” and “Cripple Creek.” They also did a tasteful semi-bluegrass rendition of “He’s My Friend,” a Meredith Willson song from “The Music Man” that probably reflected their then recent appearances on that composer’s television special.

They also did some newer numbers like Bob Dylan’s “Girl From the North Country” and “It Ain’t Me Babe.” The hit from the album, “Tupelo County Jail,” an early Mel Tillis composition that had been a hit for Webb Pierce a decade earlier, reflected in large part their approach to amalgamate country and bluegrass in a manner that also made it acceptable to folk fans as well. My own favorite, a comedy tune by Clement, “My Dirty, Low-Down, Rotten, Cotton Pickin’ Little Darlin’,” satirized typical country and western lyrics and featured Roni’s vocal lead and Donna’s harmony singing. Her lead mandolin on all the instrumental breaks managed to combine musical excellence with the mood so well that even the F-5 seemed to have a tongue in its cheek.

The next three Stoneman albums tended to follow in this pattern of spotlighting the group as a bluegrass/country/folk/old-time crossover band which indeed is what they were. Pop did his old-time numbers such as “Katie Klein” and “The Poor Tramp Has to Live” while the group did such bluegrass standards as “Ole Slew Foot,” “Nine Pound Hammer,” and “Roll In My Sweet Baby’s Arms,” along with instrumentals like “Bluegrass Ramble.” Roni did comedy songs including “Ride, Ride, Ride,” and “Dirty Old Egg Suckin’ Dog.” Clement apparently aimed the country material toward the charts, being especially successful with his own “The Five Little Johnson Girls” which ranked high on the charts for several weeks. “Back to Nashville, Tennessee,” “West Canterbury Subdivision Blues” and “Christopher Robin” also did well on the Billboard listings. The presence of songs like “Don’t Think Twice It’s All Right” maintained their standing with folkniks while “Hello Dolly” and “Winchester Cathedral” continued to display their ability to adapt popular music to their style.

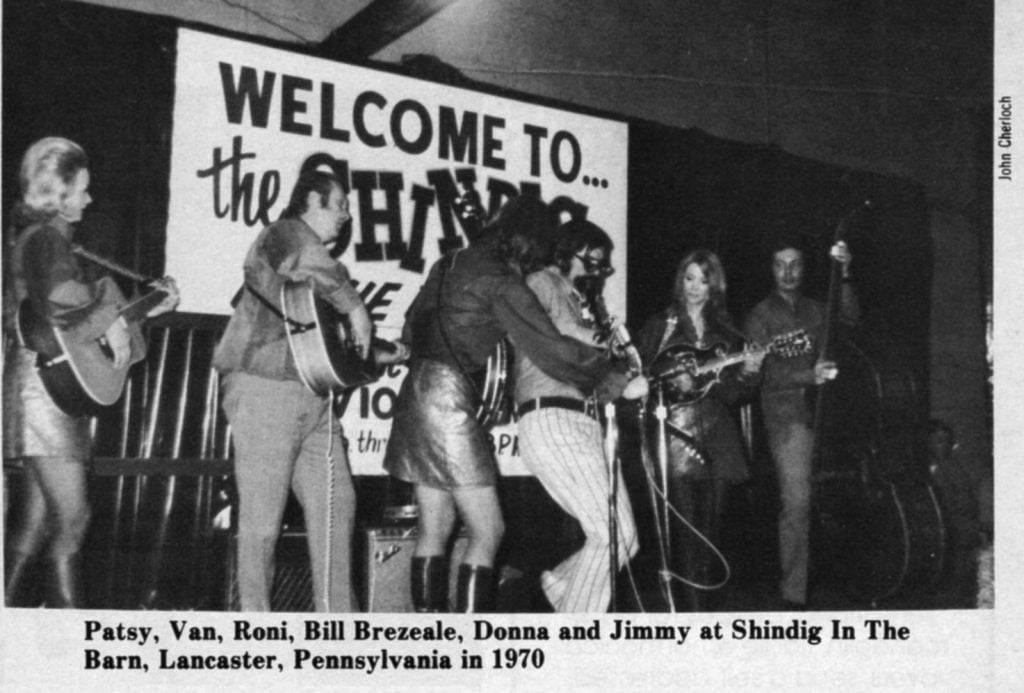

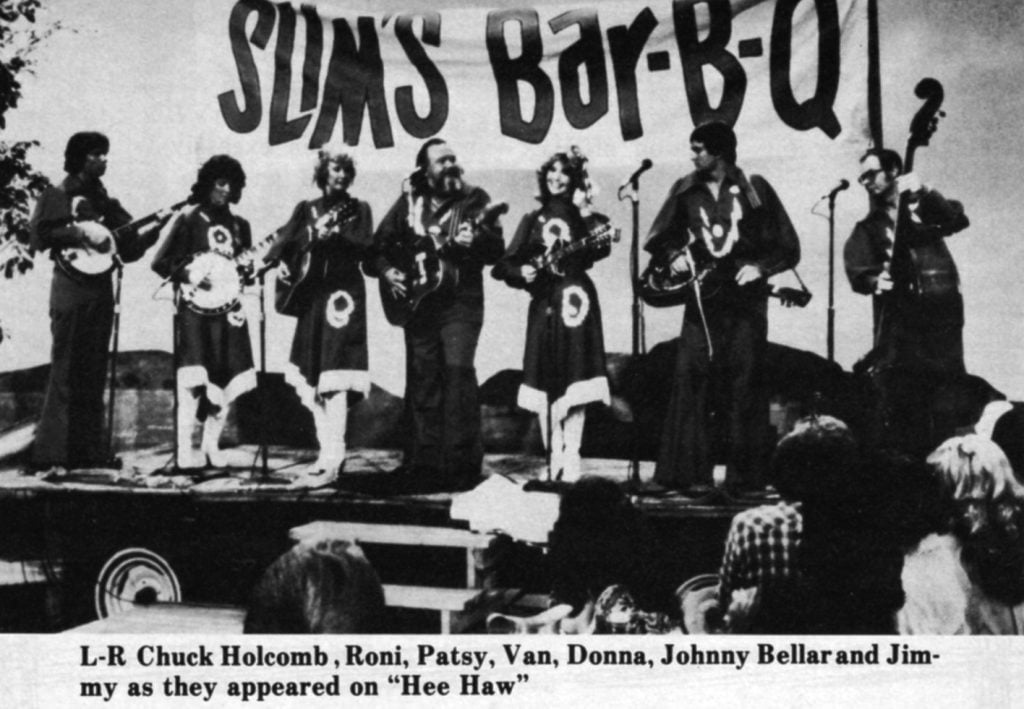

The Stonemans also filmed a syndicated television show for three and one-half years beginning early in 1966. By July, fourteen stations carried the one-half hour weekly program and within a year some forty markets heard the program sponsored by Gingham Girl flour. Roni’s banjo and comedy along with Donna’s dancing and mandolin style captivated millions of video viewers. Pop’s old-time songs, Scotty’s fiddling (although he became increasingly an off- and-on band member from this point), Van’s singing, Jim’s bass, and also Jerry Monday on Dobro made their show an appealing one. Other family members sometimes guested on the program.

The Stonemans played numerous live shows including a long stint at the Black Poodle, one of the first high quality Nashville night clubs to feature country music. Certainly they had made a major and favorable impression on their second entry into Music City. In 1967, the CMA selected them as the Vocal Group of the Year (the only time a bluegrass oriented act ever received the honor other than the Osborne Brothers in 1971). Unfortunately, by this time, Ernest V. Stoneman’s earthly days were becoming numbered. In early April 1968, the Stonemans finished their fourth MGM album with the next one scheduled to feature his talents throughout rather than just one or two numbers. According to one story, Donna predicted that he would not live to do that album on the night they finished the final session of “The Great Stonemans” at Bradley’s Barn. As events developed, the band went to Texas the next day where Pop became ill and subsequently hospitalized. Flown back to Nashville, he survived an operation, but passed away some two months later on June 14,1968. During his final illness, he asked Patsy to take over his place. True to her promise, she rejoined the band and has maintained some of his old-time sound to this day.

Twice this venerable patriarch of country music, Ernest V. (Pop) Stoneman, had made his way to the top. The Great Depression curtailed the first one, but surrounded by offspring and through thirty years of poverty, hard labor, and a dazzling quintet of superpicker children, he did it again. The second ended —to paraphrase a couple of his favorite hymns —only with “The Great Reaping Day” and dwelling on the “Hallelujah Side.” Scholors and record collectors have long recognized his entire role in the development of country music. But sad to say, the Nashville Establishment apparently saw only the last two years of a forty-four year career that went not only from cylinders to stereo, but also from the one-room school and primitive radio to the color television network special. One would hope that CMA members will yet see fit to enshrine his memory through election to the Hall of Fame.

Following Pop’s death, MGM put together a good memorial album comprised of four cuts from previous releases and seven of material from the sound tracks of the TV shows. They also waxed a Christmas album which spotlighted each member’s instrumental skill, including a particularly appropriate recitation by Roni entitled “Christmas Without Dad” plus an excellent version of Tex Logan’s “Christmas Times A Comin’.” The also continued to receive CMA nominations both for Best Vocal Group and Best Instrumental Group for the next five years.

Late in 1969, the Stonemans still under the recording direction of Jack Clement, signed with RCA Victor. Their first album, “Dawn of the Stoneman Age,” continued the pattern of the MGM days of displaying a broad range of material. “Banjo Signal” illustrated Roni’s and Donna’s bluegrass instrumental virtuosity on the old Don Reno tune and Patsy did a quality recording of “Wildwood Flower.”

Although every Stoneman got in some good moments and in retrospect the album is pleasant middle-of-the-road country, traditionalists groaned increasingly. Patsy complained in John Grissim’s book Country Music: White Man’s Blues that their sound had been excessively diluted by overproduction and too many session sideman. RCA promised changes, and although only Stonemans participated in the albums, “In All Honesty” and “California Blues,” the sound remained about the same.

To be sure some good musical moments can be found from a traditional viewpoint. Donna did a fine mandolin original, “Colossus” which received accolades of praise in Rolling Stone and she and Jimmy showed some good mandolin-bass interplay on a tune entitled “Jimmy’s Thing.” Patsy led on old-time numbers like “Somebody’s Waiting For Me” and “Little Ole Log Cabin in the Lane.” Van had a top-flight performance in “Best Guitar Picker.” Several songs display their solid vocal harmonies. Roni’s “All the Guys That Turn Me On, Turn Me Down,” a comedy number, ranked with some of those Jack Clement penned earlier. In fact, the latter song got onto the soundtracks of the Country Bear Jamboree at Disney World. Of course, there wasn’t a whole lot of bluegrass in it, but in all fairness to the Stonemans, they never claimed to be a bluegrass band. They were —and still are —a country group that plays a lot of bluegrass. More often than not, they play it very well, too, although it hasn’t always shown up on their recordings. However, in retrospect, the Stonemans hardly rank as unique in this area either.

In talking to Donna and Patsy, one gets the impression that they feel a little hurt by some of the criticisms leveled at them by hard-core bluegrass fans. Looking back over the past twelve to fourteen years, it does indeed seem that we traditionalists have expected too much from them because of their heritage. Those who loved Pop for his continued devotion to old-time complained of the children’s excessive bluegrass orientation while the one hundred percent devotees of the latter style griped that the Stonemans became excessively modern country in their approach.

Fans seemed unwilling to accept them on their own terms as traditional and bluegrass-oriented musicians providing quality entertainment in a variety of styles. Donna perhaps expresses their approach best when explaining that she “loves bluegrass music but… not a steady diet of it.” Going further, she says “I like it all mixed” because she also loves “the commercial sounds.” Certainly, this viewpoint coincides with that of many fans. The Stonemans have just packaged the product within one group in the manner to appeal to a listener who can applaud Bill Monroe or Ralph Stanley one minute and then cheer for Merle Haggard and George Jones the next. Patsy echoes similar thoughts with “if we do something that you don’t like, stick around because we’ll do something you will.”

Looking backward in perspective, the purists among us need to be reminded that even the recognized saints of the bluegrass world have occasionally recorded with electric organ accompaniment and waxed rhythm and blues/rock and roll songs. Perhaps in many respects, the Stonemans in that era were merely a little ahead of their time.

The irony of much of this further comes in the fact that much of the country mainstream persisted in seeing the Stonemans as being too traditional. Their RCA material did not score on the charts in the manner of their MGM songs. For Donna, this situation became increasingly frustrating and led to dissatisfaction with “the phoniness of the business.” The deejays did not give their records sufficient airplay. She grew “tired of music.” She had “danced and struggled for twenty years” and although the Stonemans had accomplished much particularly from 1965, they still had little security in the uncertain world of show business. Roni quit soon after doing the “California Blues” album to go on her own.

However, for Donna LeVerne Stoneman, her personal frustration soon outweighed the professional concerns. Her marriage to Bob Bean, who served as the Stonemans manager, a long-time and stable union especially by show business standards, “went on the rocks.” Unlike many male musicians, Donna had clean living habits and in other respects “never had but one boy friend … and married him.” As she struggled to cope with a disintegrating home situation, “her life became black” and she “considered suicide.” At first Donna blamed God for her misery, but in desperation she finally asked His help. Gradually, she began to feel more at peace although the marriage finally terminated. Connie Smith, country music’s best-known born again Christian, repeatedly proved herself a true friend and source of comfort through these trying times as to a lesser extent did Skeeter Davis.

Donna resettled in a small apartment with a girl from New York named Cathy Manzer. The latter had earlier cowritten a song with Donna entitled “Proud to be Together (Happy to be What We Are)” and had worked with the Stonemans for about a year after Roni’s departure playing electric organ and helping on vocals. Having dedicated her whole life and talent to the service of God, she and Cathy sang and testified in churches never charging fees or asking for money although they did accept freewill offerings. Through frugal living and good credit, Donna proudly proclaims that her every need has been supplied, she’s never been in want, and is free of debt. She cites numerous examples to prove her point.

In one of her early church experiences, a minister who knew the Stoneman’s musical background asked Donna to do the “sanctified” “Orange Blossom Special” in a service. Although a little hesitant, she complied and when the congregation became emotional, she initially feared that God’s wrath had come down for playing a secular tune in church. However, when finding out that it was simply “their way of being blessed,” Donna restored the tune to her repertory. When Donna and Cathy waxed a gospel album a little later, “Orange Blossom Special” was included as one of the cuts.

During her period of depression and the adjustment that accompanied her conversion, Donna developed an interest in painting. An art store attendant suggested acrylics and over a two-year period she produced some 500 paintings, largely of landscapes. In May 1973, she gave an exhibition and received some television publicity. She sold a number of the paintings that night. One of her winter scenes titled “The 8th of January” after the traditional fiddle tune played by brother Scotty appeared on the cover of a country music magazine. Others of her work have been purchased by Dolly Parton, Jeanie C. Riley, and Sammi Smith. Roni has another one of particular significance to the Stonemans, an impression of the homey little cottage in Carmody Hills that sheltered them in their youth. Modest about everything in her life —except the depth of her faith and possibly her mandolin stylings—Donna simply views her artwork as another way that God provided for her sustenance.

One should not assume, however, that Donna’s life has been all joy since her conversion. She has had to cope with such difficulties as brother Scotty’s tragic death in March 1973, mother Hattie’s recurring illnesses and death in July 1976, and a delicate operation on her own back that same spring. Nonetheless, faith helped sustain her through these trials and she is convinced that prayer extended Hattie’s life for a year and a half after an earlier heart attack. Furthermore, in pursuing her religious goals, she has often sold once-prized personal possessions.

Donna’s one excursion into secular music during the period came when Tom T. Hall recruited her to play mandolin on his “Magnificent Music Machine” album of bluegrass songs. Unaccustomed to the large number of musicians used on latter day sessions, she experienced some surprise when young Jody Drumwright and veteran Bill Monroe also appeared. Donna recalls that the latter left after waxing “Molly and Tenbrooks” and remarked that in an earlier day she likely would have reacted similarly. Three mandolins for one album! Nonetheless, she remained and made her contribution to an album that has been well received in both the country and bluegrass fields.

After about 1977, Donna and Cathy Manzer each went their own ways. They remain friends, but as Donna stated their musical styles did not really complement each other although “they sounded okay together.” With divine help, she managed to adapt as a solo gospel singer and also received the call to preach. Both of these constituted a strong break with the past as she had sung only harmony with the Stonemans, switching parts with one of her brothers on the notes she couldn’t reach. Despite her extroverted dancing image, she had been very shy on stage when it came to talking and said very little.

Nonetheless, Donna plunged herself into deep biblical study which is now in its eighth year. A brief conversation can easily convince any skeptic of the depth and sincerity of her faith and conviction. In October 1980, she became a licensed minister and an ordained one in November 1982. She speaks “a gentle message … from the scriptures” rather than the “fire and brimstone” approach used by some evangelists. To date, her ministry has taken Donna to some unusual places and resulted in some rewarding experiences. In the spring of 1980, she spent six weeks in England and Belfast, Ireland. In the summer of 1981, she preached in the Montana State Prison and on Indian Reservations. Other aspects of her evangelism include a regular newsletter, The Table Is Spread, and a series of inspirational articles in an Alabama paper and another one in Great Britain.

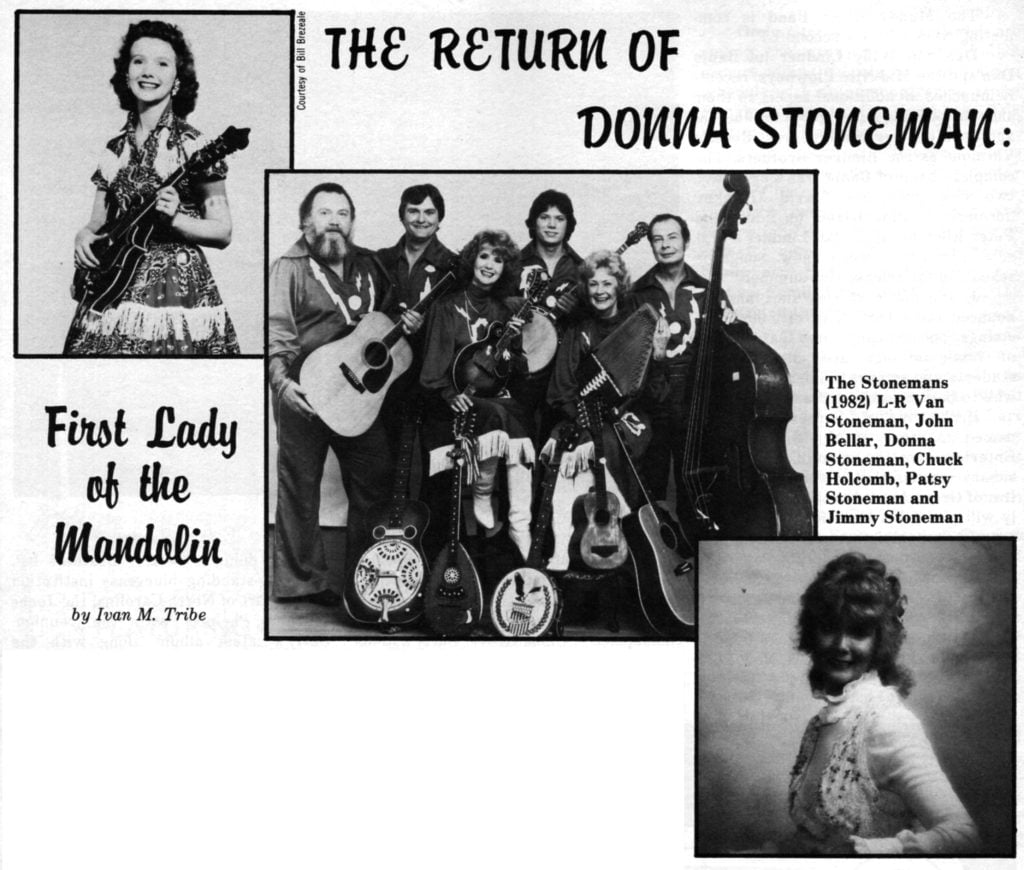

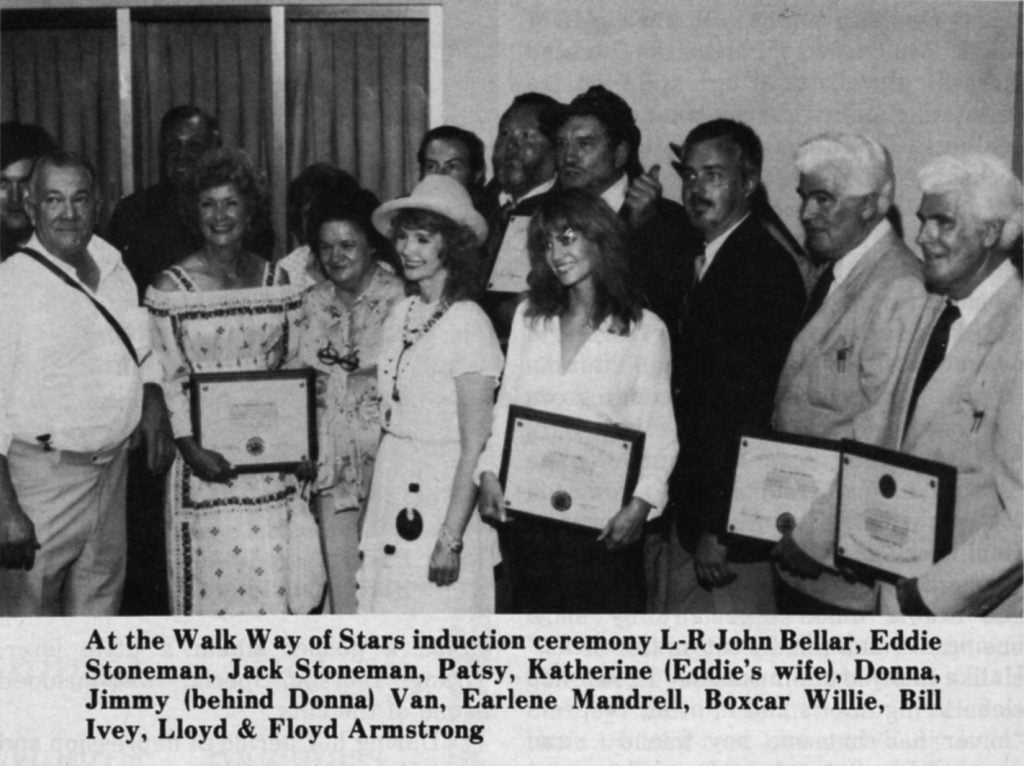

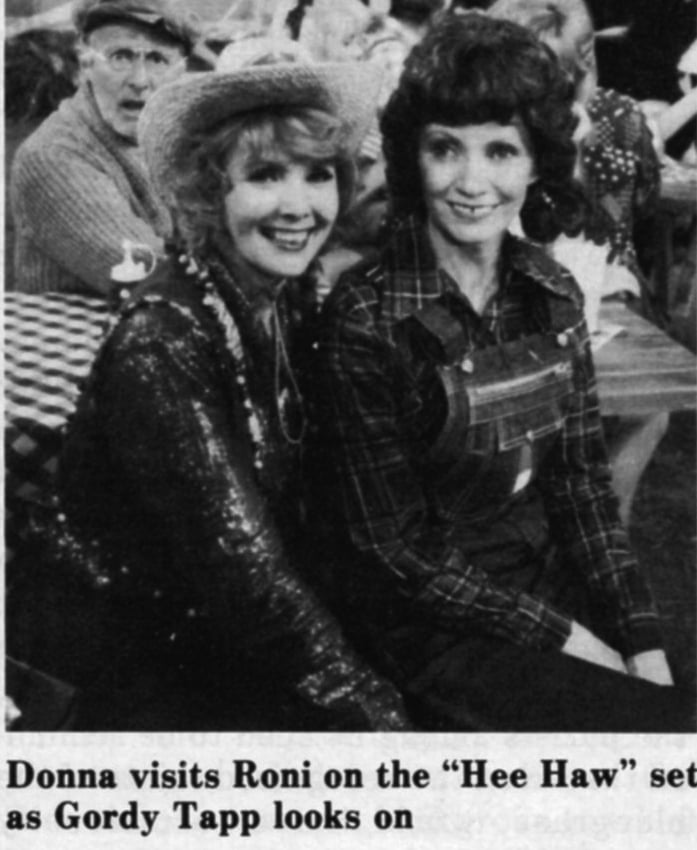

Since fall 1981, Donna has also rejoined the Stonemans on a regular basis. In late October, the group played a show at the Roy Acuff Theater in Opry Land and presented Patsy with flowers on her tenth anniversary in charge of the band. She also participated in the CMH double album set released in summer 1982. Ten of the Stoneman children are heard on these recordings which certainly represents the best disc work the group has performed in over a decade. Three numbers feature Donna who does lead vocal on “Life’s Railway to Heaven,” and mandolin instrumentals on “Under the Double Eagle” and “Orange Blossom Special.” In addition to the usual top-notch work by Jimmy, Patsy, Roni, and Van, lesser heard Stonemans like Eddie, Grace, Jack, Gene, and Dean all do numbers on this album as do some of the grandchildren. Through Tree International of Nashville, the Stonemans are also at work on a autobiographical book which will include the entire family and perhaps form the basis for a television series.

Back with the band after a near decade of absence, Donna reports that she is “enjoying it more than ever” and is thankful that “the Lord put music back in my heart.” She counts among her musical possessions several original mandolin tunes still waiting to be recorded. Donna has two main purposes in life to fulfill—the first being to continually “uplift Jesus Christ” and the second to “help my family.” Citing Psalm 149, she has renewed her family dance routines, too, although she did cease this practice for a three-year period prior to 1976.

In retrospect, the musical world has seen many aspects of Donna LaVerne Stoneman since her poverty-stricken early childhood. Initial press coverage described her as “clean, sweet, and well behaved” but “obviously undernourished” with “dark circles around her violet eyes.” Growing to adulthood, she blossomed into a lovely young lady distinguished by superb mandolin picking talents and unique on-stage dance steps that led to a description of her as the “icing on the cake” of the Stoneman group.

Jethro Burns, himself no slouch on the instrument, perhaps paid her musical talent its highest compliment when he reportedly answered a question propounded to him on the Mike Douglas Show as to the best mandolin player with “Donna Stoneman is the best there is.” A decade later she modestly described herself as an “ex-country entertainer turned evangelist for Jesus Christ” and a “little hillbilly gal from Galax, Virginia and now Nashville.”

Now having combined her ministry with music and rejoined the Stonemans as well, Donna should be able to fulfill both her evangelistic and musical missions. Of course, nobody is perfect and the hard-core of traditionalists among us may wish that she would toss away that electric pick-up on her F-5. However, whether she does or doesn’t is irrelevant in the long run. One thing remains certain, if you need or wish to see good entertainment, hear an inspirational sermon or a well-played mandolin, or just listen to a pleasant bluegrass-country-gospel song, Donna Stoneman will do an excellent and fantastic job.

Share this article

3 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Interesting

I miss my little friend Donna Stoneman. I’ve shared in her present grief of Ronis passing.

I feel privileged and honored to become a friend of Donna’s quite awhile ago now. We sang together on various occasions

Donna preached a wedding and we played and sang. We also sang at a funeral at one point. To me, at the time Donna seemed very much like a sister. I have missed her all these years and hope I can find her.

I sure would love to re-kindle the friendship fire with the iconic Donna Stonenan. It’s been over 30 years since I and friends and family were entertained and blessed by Donna’s talent at my wedding In Nashville. It was truly an honor to have met both her and Kathy Manzer and share our music together in their apt. In the late 80’s early 90’s. I had just moved to Nashville.

My name is Bill Young and I’ve been living and performing in the shadow of the Great Smoky Mtns. Of East TN.

If there’s anyone that could assist me in re-connecting with her, I would be Sooo appreciative !

My e-mail is: [email protected].

Text or call (865) 654-9395.

Sincerely,

Bill Young