Home > Articles > The Archives > The Osborne Brothers— Part Two: Getting It Off

The Osborne Brothers— Part Two: Getting It Off

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1972, Volume 6, Number 8

(Part One: Family and Apprenticeship appeared in Bluegrass Unlimited Volume 6, Number 5, September 1971)

(To read part one of this series, click here: https://www.bluegrassunlimited.com/article/the-osborne-brothers/)

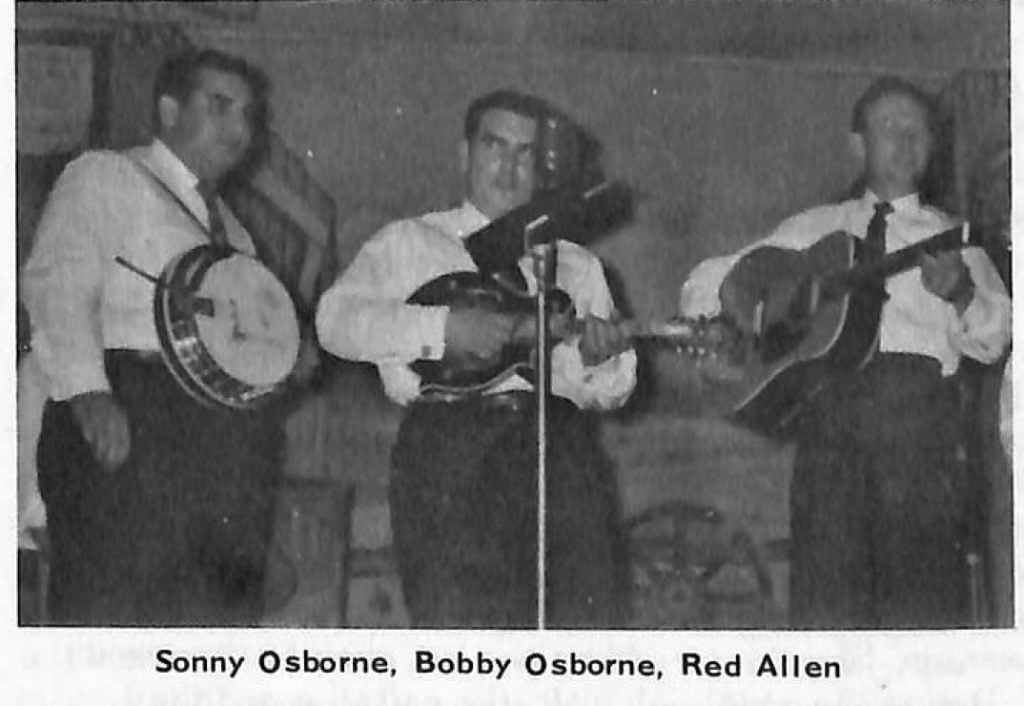

At the start of 1956, Bob and Sonny Osborne were once more at home in Dayton, Ohio, playing the local clubs. Enos Johnson, who had worked with them in Knoxville during 1953-4, and in 1952-3 with Sonny in the Dayton area, was their guitar player. One night Red Allen, like the Osbornes, a Kentuckian living in the Dayton area and a former Gateway recording artist, was asked to substitute for Enos. The upshot was that Red became the regular guitarist in the group. Fiddler Art Stamper, who had recorded with the Stanley Brothers and was at that time working with Red Allen, also joined the group at this time. In February or March of 1956, they recorded eight instrumentals for Gateway records. This was their last session for that company and musically the most interesting.

Bobby: “We messed around, played a few clubs (in Dayton), and Tommy Sutton helped us get a contract with . . . MGM Records. He was a disc jockey at WPFB at the time — early morning show and the afternoon.”1 In April, 1956, Tommy Sutton took an audition tape with him to Nashville and played it for Wesley Rose of Acuff-Rose Music. The tape included Ruby, and it led to a recording contract with MGM.

This contract came at a time when country music was facing intense competition from rock ’n’ roll. Elvis Presley’s records were number one on the Billboard country singles charts through most of 1956. Country music recording executives were frantically looking for new sounds that could compete in the new context created by Elvis. That a group playing country music of the older style—in 1956 “bluegrass” was a word known to few people, and bluegrass musicians thought of themselves primarily as country musicians—could land a recording contract with a major label such as MGM spoke well for the quality of the group. The music of the Osborne Brothers and Red Allen was conservative in contrast to that of singers like Elvis Presley, Marty Robbins and Sonny James, big sellers on the country charts at that time. Nevertheless, the group was still evolving musically, and the very first MGM recording session introduced innovations in bluegrass style which have become the stylistic trademarks by which the group is still known.

Bobby had been singing Ruby since his first days as a professional in 1949. When he recorded it for the first time in 1956, a new dimension was added: twin banjo accompaniment, in the style of twin fiddles. The idea of multiple instruments playing voice-like parts was not new to bluegrass—Mac Wiseman had introduced twin fiddles on his early (ca. 1951) Dot recordings. And long before that, in the thirties and forties, they had been used in the western swing bands of Bob Wills, Milton Brown and others. Bluegrass musicians had been experimenting with twin banjoes during the early ’50s, but it was not until the Osborne Brothers and Red Allen’s Ruby that the sound was introduced on record.

Originally Sonny had asked Noah Crase to accompany them on second banjo at that first MGM session in Nashville on June 21, 1956, but at the last minute Noah could not make the trip, so Bob ended up playing the second banjo on Ruby.

Ruby was released in the early fall of 1956. This led, indirectly, to their return to WWVA, as Sonny explained: “ . . . While we worked at Wheeling with Charlie Bailey . . . I . . . became very good friends of Paul Meyers, who was the program director or program manager at Wheeling … I knew he was manager of the Jamboree . . . When Ruby was released we called and got a date up there.” They did a guest appearance and were signed on as regular members of the WWVA World’s Original Jamboree in October, 1956. Art Stamper did not accompany the group in its move to Wheeling. The band on WWVA in the first year and a half consisted of Johnny Dacus, fiddle (he later played fiddle with Jimmy Martin); Ricky Russell, dobro; and Ray Anderson, bass. This band did not appear on any of the Osborne Brothers and Red Allen recordings, but those who have heard recordings of their shows or remember their WWVA broadcasts can testify to the brilliance of the group.

At their second MGM session in November, 1956, three of the four songs recorded were twin-banjo efforts which attempted to repeat the success of Ruby. But by this time, because their instrumental ability was established, the band was more interested in their vocal trio. Bluegrass enthusiasts sometimes forget (or resent) the fact that the average country music fan plays much more attention to the vocal aspects of a song than to the fine points of instrumental style. The Osbornes saw this clearly, and felt that it was in the best interests of their career that they turned increasingly to the development of a unique singing style. It was at the third MGM session, in July, 1957, that they recorded the song which was to establish their special trio sound.

“Well, Dusty Owens had written the tune Once More while we were working on Wheeling, and me, Bobby and Red . . . actually, where it started was in the car. We were coming back from Wheeling to Dayton and we started rehearsing . . . you know, singing it, ‘cause we liked the tune awful well and that’s where the top lead and that came from. Actually, I think in Zanesville or Cambridge—Zanesville I guess it was . . . finally we just parked the car and set there and learned the tune . . . ; That’s where it really started. . . . The harmony that we do now is much more complicated. Back then we just used a regular high lead (sung by Bobby) and the two lower parts, the baritone (Sonny) and a low tenor (Red).”

The group was excited about the new sound of Once More, convinced that they had a unique commercial sound that would sell records. However, the MGM A&R man Wesley Rose was not convinced. It took some talking for them to get the song included in the recording session instead of another Ruby type song with twin banjos.

This session was also significant in that it was the first bluegrass recording session in which drums and dobro were used together. Sonny: “They sold us on it … I guess that’s the first time we’d ever used drums . . . and it . . . gave the music such a lift…”

Bobby: “We were the first ones to use a dobro and drums together on a session too . . . The dobro (was) a popular instrument at that time. We only did about three sessions with it and we left it go.”

This July 1957 session was for a number of reasons the Osbornes’ crucial one. Having established themselves as masters of the art of classic bluegrass, they were successfully introducing their own musical elements to their sound, adding techniques and instruments not being used by other bluegrass groups. In this session as in others to come, some of the innovations were suggested by the record company. Others were their idea, but at each step since then the Osbornes have maintained what they considered the important part of their sound, while experimenting with various aspects of it. It is at this point then, that their style began to diverge from that of “hard-line bluegrass.”

In devising a trio in which the lead voice was the highest, the roles and images of the singers in the group were significantly altered. In modern country-western music the lead singer is, in effect, the center of attention for the audience; the star. When Bill Monroe, who had never sung lead, started his own band in 1938, he had to deal with this fact. He solved the problems it presented by singing lead on the verses and tenor on the choruses. In this way he preserved the reputation he had earned as a tenor singer and developed a new reputation as a lead singer. Bob Osborne, too, switched parts this way sometimes, especially with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers. With the high lead harmony, Bob Osborne solved the same problem Monroe had solved earlier, but in a different way—by singing lead throughout the song and at the same time singing the highest part. Moreover, Sonny, singing the baritone, had the middle voice in the harmony which was the next most prominent. Thus this shifting of musical roles freed the Osborne Brothers from dependence upon the reputation of any single guitarist/lead singer, since the guitarist was now singing the lowest and generally least discernable part. From this time on, changes in band personnel with the Osborne Brothers became more manageable and, in terms of the band’s overall sound, less significant.

Early in 1958 the Osborne Brothers recorded for the last time with Red Allen; he left the group in April, 1958. After this point the group was to be known simply as “The Osborne Brothers” and other members did not receive billing, although their guitarists have been given publicity on record labels and jackets, as well as at personal appearances. After Red Allen’s departure succeeding guitarists played more straight rhythm and less bass line runs. Some listeners (especially in the early ’60s) saw this as a lack of technique on the part of guitarists, but this in fact was due to Bob and Sonny’s feeling that guitarists who threw in “fancy” runs all the time often did not keep good rhythm.

From April, 1958 to early 1959, the guitarist and third voice in the trio was Johnny Dacus, who had been their fiddler. Dacus left the group just before their next recording session in February of 1959. Ira Louvin filled in for him on the one trio recorded at this time (Give This Message to Your Heart). Two other songs featured the unusual sounds of Ray Eddington’s tipple; an out and out rock attempt, There’s Always a Woman marked this session, like the preceding one, as one of experiments.

During the middle of 1959, the guitarist and third voice in the trio was Ray Anderson, a disc jockey from Washington Court House, Ohio, who had earlier played bass with the group. Bob and Sonny had previously recorded a number of songs for the Mountaineer label with him in October of either 1957 (according to Red Allen who played bass on the session) or 1958 (according to Bob and Sonny). Anderson did not record with the Osbornes on MGM. The October, 1959 issue of Esquire magazine carried an article by Alan Lomax entitled “Bluegrass Background: Folk Music with Overdrive.” Among the illustrations by artist Thomas Allen (who later did most of the Flatt & Scruggs album covers) was a picture of Bob, Sonny and Ray Anderson on the WWVA stage.

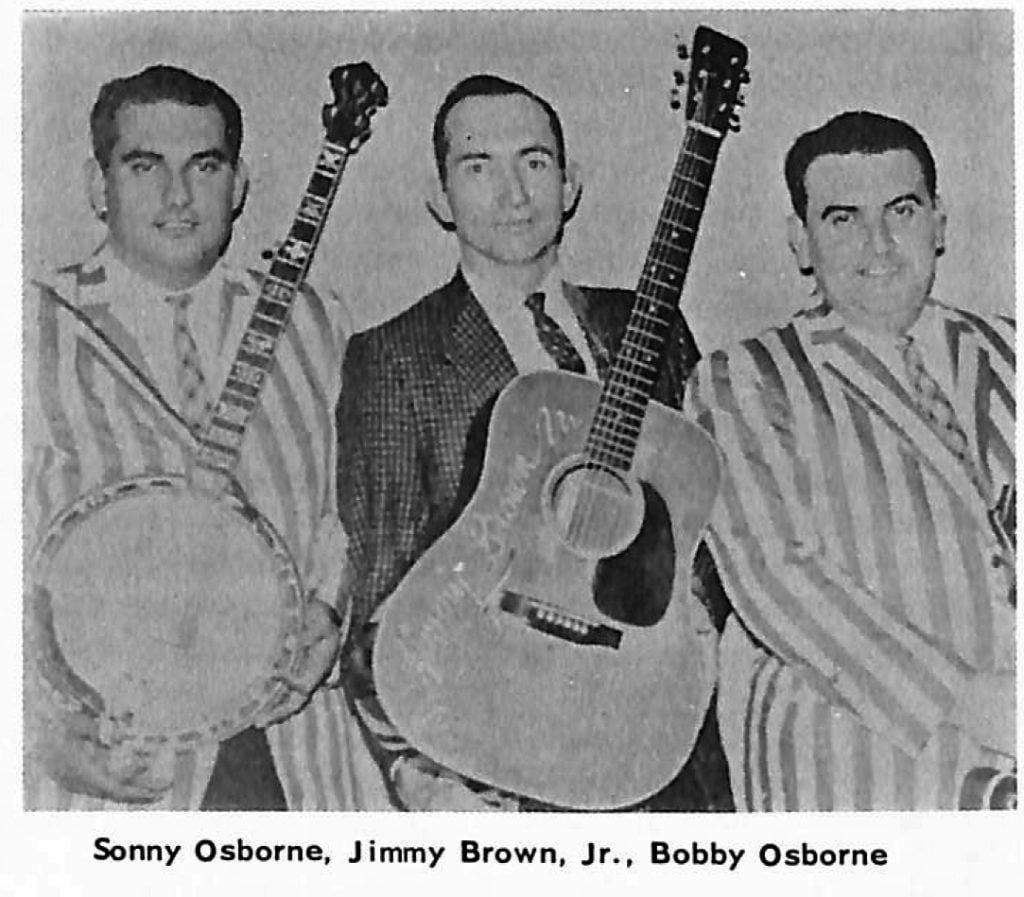

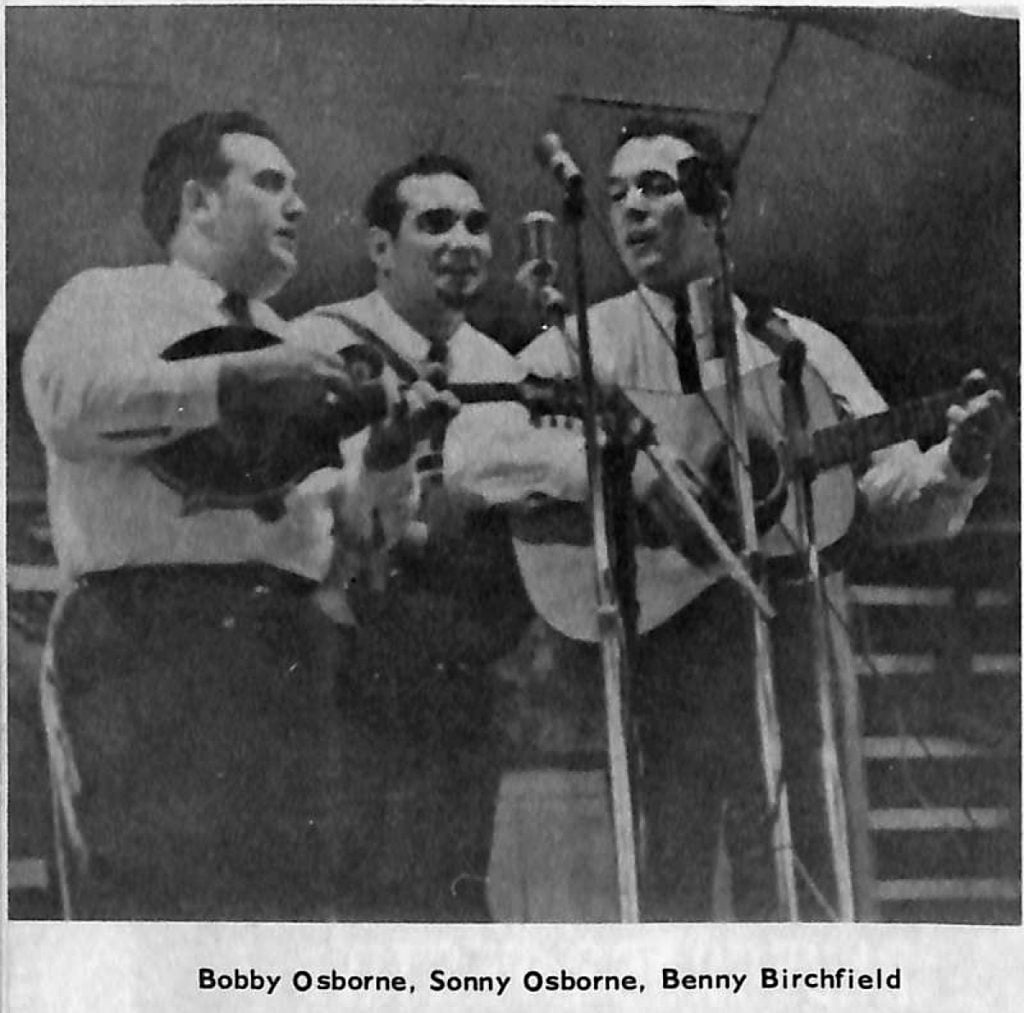

In the fall of 1959, Benny Birchfield and Jimmy Brown, Jr. joined the group as bassist and guitarist respectively. The next MGM session reflected the solidarity of the new trio sound on three songs; Jimmy Brown, Jr. was to remain with Bob and Sonny longer than any previous singer-guitarist they had worked with to that point.

In February of 1960 this band played what is generally considered the first college concert played by a country bluegrass band. The time was ripe; Earl Scruggs played at the Newport Folk Festival the previous July; Flatt and Scruggs had been featured on a national TV show entitled “Folk Music 1959” the same summer, sharing the spotlight with Joan Baez and John Jacob Niles. For several years curious folk music fans had been attending bluegrass shows such as those at New River Ranch in Rising Sun, Maryland, and bluegrass bars like the Crossroads, near Washington, D.C. where the newly-formed Country Gentlemen were appearing nightly. But the interest was largely “underground” and when the Osbornes arrived at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio (only a few miles from Dayton), they were prepared to play rock ’n’ roll. They were very much surprised to find an audience requesting bluegrass standards of the kind they had stopped performing regularly when they left Gateway Records—songs such as Molly and Tenbrooks, Earl’s Breakdown, and Little Maggie. The audience was enthusiastic about the vocal and instrumental ability of the group which was obviously much more professional than the two college groups who shared the billing. The audience was also somewhat confused by the presence of what they considered “corny” country songs like Pick Me Up on Your Way Down, and the down home comedy routines. Some even giggled at Bob’s serious announcement of “Hymn time.” As other bands were to discover, college audiences liked bluegrass better when it was presented to them as “Folk Music” rather than a kind of “Country Music.” Nevertheless, it was a successful concert, and following the Antioch concert, the Osbornes played other college concerts, and appeared before “folk music” audiences at the Newport Folk Festival, Boston’s Club 47 and other similar places. However their basic audience was, and continues to be, the mainstream country music audience. This reflects economic facts—the “Folk” audience is both more fickle and smaller in number than the country music audience. It also reflects esthetic preferences, for the Osbornes were not then interested in doing other people’s tunes and bluegrass “oldies”, which seemed to be one of the requirements of the “folk music” boom. Their next recording session, in the fall of 1960, indicated quite clearly their continuing interest in developing a distinctive personal sound.

The four songs recorded for MGM in October 1960—Fair and Tender Ladies, Each Season Changes You, Black Sheep Returned to the Fold and At the First Fall of Snow—were all trios, and were recorded, for the first time in the Osborne’s career, with pedal steel and electric guitar backing. Sonny explains, “that was our idea . . . ‘cause we needed more—in Fair and Tender Ladies we all three sang all the way through it. There was no background. Bobby couldn’t play background on the mandolin, I couldn’t play background on the banjo.

We needed something to fill it up on that so we used Hank Garland…and…Peter Drake.

These recordings, especially the single of Fair and Tender Ladies and Each Season Changes You, were well received. Fair and Tender Ladies was one of their most requested pieces through the ’60s. Thus, not only was the session successful musically, it also seemed to do well with record buyers.

On February 15 and 16, 1962 the Osbornes recorded an instrumentals album for MGM. On the 17th was a singles session. Later in 1962 Jimmy Brown, Jr. left the group. He was replaced by Benny Birchfield, who had been playing bass and second banjo on the double banjo tunes since 1959. The trio sound that the group was able to get with Benny was outstanding; the next and last session for MGM, on January 9-11, 1963, featured a number of interesting performances, some of which were released on their MGM album “Cuttin’ Grass!”

It appears that at this time MGM was uncertain about the proper way to market the Osbornes. Their L.P. jacket notes stressed the popularity of bluegrass in colleges, etc., but in an inept sort of way which made MGM sound rather “out of touch”, since they had no idea (apparently) why college kids were digging bluegrass. Their singles, on the other hand, were in large measure novelty numbers which didn’t really get off the ground. The good ones, like Poor Old Cora, got poor distribution and were not issued on L.P. The one single from the last MGM session was a coupling of Boudleaux and Felice Bryant’s Lovey Told Me Goodbye (the A side) with Mule Skinner Blues (the B side). As happens so often in the world of popular music, the B side was the one that sold the record. It was during Mule Skinner Blues popularity that the Osbornes left WWVA and the World’s Original Jamboree, where they had been members for seven years.

Footnotes:

- Bill Emerson’s recent very interesting interview with the Osborne Brothers which brings up a number of details not covered in my first installment, lists WONE Dayton as the station with which Tommy Sutton was affiliated at the time of the MGM audition. Bill Emerson, “The Osborne Brothers: Getting Started,” Mule Skinner News, II: 4 (July-August, 1971), 2-11.

To read part one of this series, click here: https://www.bluegrassunlimited.com/article/the-osborne-brothers/