Home > Articles > The Archives > The Osborne Brothers

The Osborne Brothers

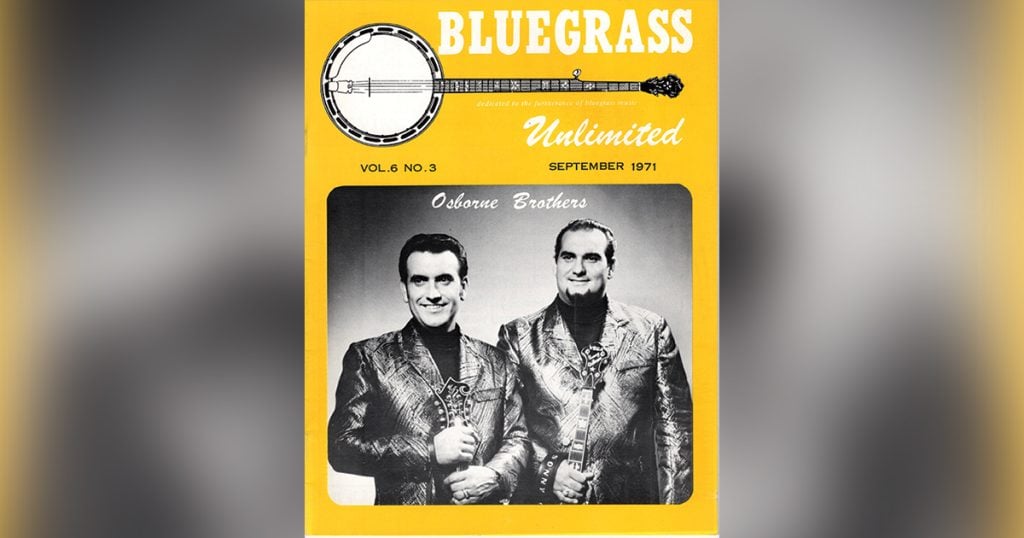

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 1971, Volume 6, Number 3

This history of the musical careers of the Osborne Brothers is based primarily upon interviews with Bob Osborne (Bean Blossom, Indiana, September 26, 1965) and with Bob and Sonny Osborne and Benny Birchfield (Columbus, Ohio, March 18, 1967). Most of the discographical data was furnished by Bob Osborne. Many important dates come from a notebook kept by Bob and Sonny’s sister Louise during the early years of their careers. I wish to thank Bob and Sonny for their interest and cooperation in this project.

PART ONE: Family and Apprenticeship

We’re the banjo boys from old Kentucky,

Let the banjos ring, ’cause we feel lucky

(Banjo Boys, Osborne Bros. MGM K13098)

During the twenties and thirties Robert Osborne Sr. had a farm about four miles outside of Hyden, Kentucky. In addition to working the farm he helped two of his brothers operate their grocery store in Hyden. For eleven years during this time he taught school in Hyden. Mrs. Osborne also taught school, but during the thirties was busy raising a family. Robert Jr. was born on December 7, 1931, Louise was born several years later, and Sonny was born on October 29, 1937. It was (and is) a happy, close-knit family, with a strong musical tradition.

Robert Osborne Sr. was a Jimmie Rodgers fan who owned Rodgers’ records (as well as some by the Carter Family) and enjoyed singing Rodgers’ songs and yodels. He played the banjo, fiddle and guitar, and it was he who taught young Bob his first guitar chords. The father and son did some duet singing together—with Robert Sr. taking the tenor part. Bob still has an old home recording of the two of them singing; “. . . can’t hardly hear it, really. But he sang tenor to Mansions For Me and Mother’s Only Sleeping and … a couple others.”

Shortly after the start of the Second World War the family moved from Hyden to Radford, Virginia, where Mr. Osborne worked at the Hercules Powder Plant. At the end of the war the family moved to Dayton, Ohio, where Mr. Osborne began working at the National Cash Register Plant. It was in Dayton that the musical careers of the Osborne Brothers began.

Even before they left Hyden, Bob had begun to listen to the Grand Ole Opry every Saturday night. His favorite singer was Ernest Tubb: ‘‘I tried to sing like him, but when I was about sixteen (1947) my voice changed and I had to take to something else.”

The first time Bob paid any attention to Bill Monroe’s music was in 1945 or 46, when Flatt and Scruggs first joined the Blue Grass Boys. “ ’Course, I was playing the guitar at the time. I didn’t even know what Bill played. I was under the impression Monroe played the fiddle until I saw him in person, in about ’47.” It was at this time that Bob started listening closely to Monroe. ‘‘I was still trying to sing like Ernest Tubb but once my voice changed why I got singing Bill’s songs and playing the guitar. I had me a thumb pick and finger pick. I seen Flatt play with one of them so I got me a thumb pick.” Shortly after this time Bob received a new D-28 Martin guitar as a Christmas present from his father.

Bob’s start as a professional musician, like his beginnings on the guitar, came through the family. A number of his mother’s brothers were active musicians. One of them, McKinley Dixon, was living near Dayton when the Osborne family moved there. He played Merle Travis style guitar. “Him and me played a little bit together and we both played in a band called The Miami Valley Playboys! This was in 1947 and 48, when the group appeared regularly on Sundays at the Apache Inn on Route 4 near Middletown, Ohio.” The first road show Bob remembers playing was with this group in Ellerton, Ohio.

McKinley Dixon’s next door neighbor, Ott Ginter, was affiliated with a radio barn dance in Middletown. “My uncle introduced me to this guy and then my uncle, he left, went to California …. Ott Ginter asked me one time, would I like to play at this barn dance in Middletown, Ohio. And I said, yeah, I’d like to play on it. So he knew somebody down there or something and made a call and got me an audition.”

Bob usually dates his career from the time of this first radio appearance in June, 1949. He had formed a band with Junior Collett, who played rhythm guitar, and Dick Potter, who played electric mandolin. Bob was playing electric guitar. On the evening of Friday, June 3, 1949, they played a tent show on the grounds of WPFB, in Middletown. Their first song was Simmertime is Past and Gone. The evening following this successful audition they played their first radio show on WPFB. At this time Bob sang a song he had learned from an old Cousin Emmy record that was at home —Ruby. “I never did sing it until I went down there. I knew it all the time, I just never sang it.”

“Now, about three weeks after that, Junior Collett, he quit the group and Dickie Potter and myself played, oh, another week or so . . . and he quit. So I played a little bit by myself …. I sang for four dollars a night down there at that place, on a Saturday night …. Then Larry Richardson from Galax, Virginia, came to WPFB. He played the banjo and I, by that time I’d kindly got a little bit interested in bluegrass music.”

Bob and Larry first played together in public at Lasourdsville Lake, near Middletown, on Sunday, July 21, 1949. Between that date and August the 12th, Larry returned to Galax and came back to Middletown, where he was hired by WPFB. On Sunday the 14th Jimmy Dickens was the star attraction in a tent show on the grounds of WPFB; Bob and Larry were one of the acts also appearing. That same day Bob and Larry quit WPFB. “I don’t know, he had some kind of a falling out with the station on account I was going back to school (in the fall) or something. I don’t know exactly what it was, but, he left the station and I decided to leave school and choose the music.” For the next two weeks they auditioned at radio stations. “We went to WLW, WSAI, in Cincinnati, WHAS in Louisville, WMOH in Hamilton, WWSO, think that’s in Fort Wayne, WONE in Dayton and WING and WHIO. And we didn’t get on there. Finally told Ohio to go to hell and forget about it . . . . (Larry) knew a guy in Welch, West Virginia at a station which no longer even exists, WBRW.” They were hired there and played their first show on Thursday night August 25th, at 11:00.

At WBRW, Bob and Larry formed a group which they called The Silver Saddle Boys. The other members were Eddie King, who played the fiddle, and tenor guitarist Buck Duncan. “We played off the station simply because . . . we could play dates at night and make a few bucks. In those days radio stations didn’t pay you nothing. And they still don’t for that matter.”

Bob and Larry stayed in Welch until October 12, 1949. “We played a square dance on top of a building up there, parking lot building. Some guy come up and ask us would we like to have a job and we told him yeah. So he got us in his car—neither one of us had a car at the time—and asked did we have a job, we told him no; if we’d like to have one, we said yes. So he got us in his car and took us to Bluefield, introduced us to people up there by the name of Rex and Eleanor Parker. They’re in Princeton, West Virginia, now, they still make records but it’s all gospel music. And they go by the name of the Parker Family now but they were at WHIS (Bluefield) at the time and we got a job with them. We was making thirty dollars a week apiece, I believe. That included a square dance on Saturday night. We started with them on October the 23rd, and we worked with them about three weeks.”

Another group playing on WHIS at that time was the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers. This group had been formed in Bluefield by radio executive Gordon Jennings, and was apparently not related to the group of the same name which Stringbean played with in Lexington, Kentucky during the thirties. Jennings had in the group a bassist, Ezra Cline, and Ezra’s nephew Charlie Cline, who played several instruments, and Bob remembers the band’s sound as resembling that of the Delmore Brothers. Jennings left the group some time before 1949, selling the name and ownership of the group to Ezra Cline. The band continued with the same sound and instrumentation until November the fifth, 1949, when Bob and Larry joined. “They offered us a job and … we help(ed) start the bluegrass for the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers and in turn why the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers . . . gave us a four-way split …. we had radio programs at 6:45 a.m. in the morning.” The band consisted of Bob on guitar, Larry on banjo, Ezra Cline on bass and Ray Morgan of Mohegan, West Virginia on fiddle. Ezra did the MC work and handled the business affairs of the band.

Bob and Larry stayed with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers for a year. In March of 1950, the group made its first recordings—four songs for the Cozy label. Recorded at WHIS, all four songs were composed by Bob and Larry. One of them was recorded later in 1950 by Flatt and Scruggs for Mercury—Pain In My Heart.

Later that same year, Bob’s younger brother Sonny, then twelve years old, came to visit him in Bluefield. At the time Flatt and Scruggs’ Mercury single of Down the Road had recently been released. Sonny liked it and one day asked Larry how he played it. Larry played it for him, but with his back to Sonny so that Sonny couldn’t see his fingers. Sonny had not previously been interested in playing the banjo, but after this incident he began to think about trying the five-string.

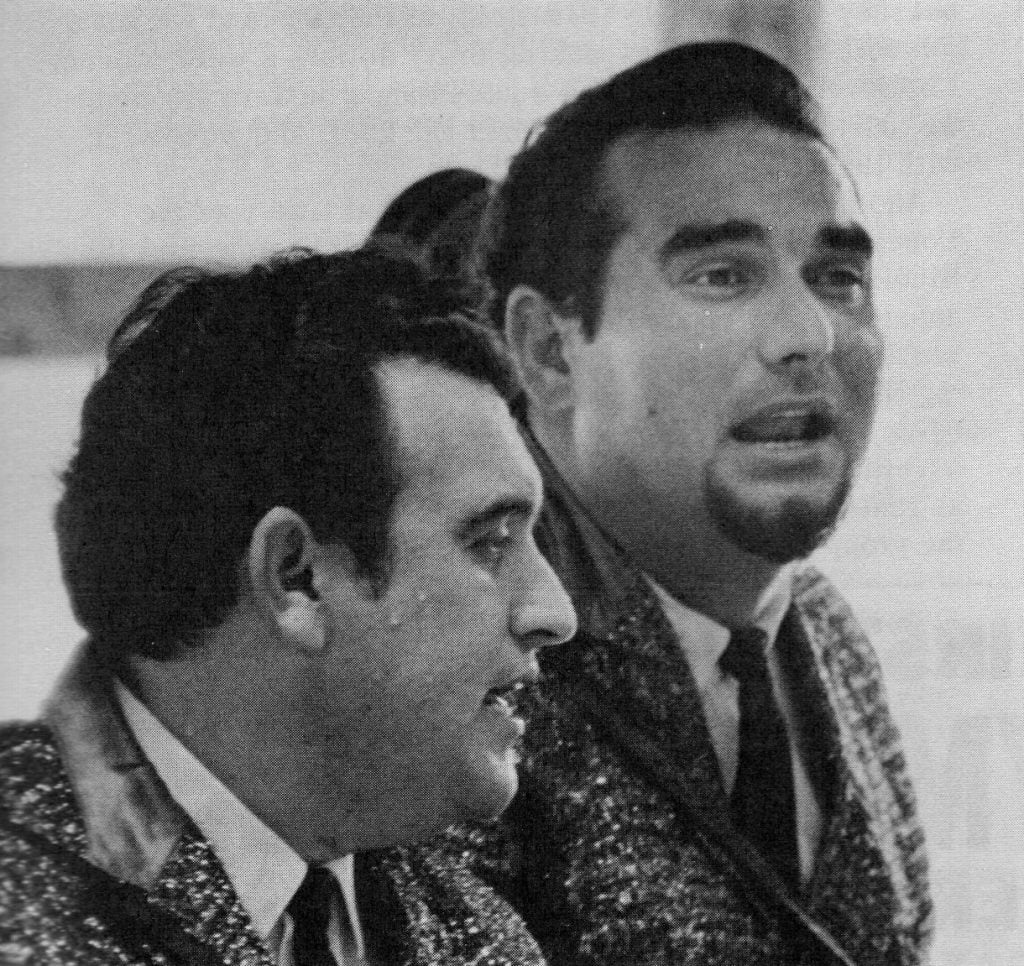

Also during this first year with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, Bob met Jimmy Martin. “Bill (Monroe) come to the State Theater in Bluefield . . . had Rudy Lyle, Jimmy Martin and Vassar Clements and Joel Price playing with him at the time. They come up here and I met Jimmy there.”

On November the fifth, 1950, one year after they had joined the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, Bob and Larry quit. Forming a group with fiddler Curley Ray Cline (brother of Charlie, nephew of Ezra), they auditioned for King Records and the Renfro Valley Barn Dance. Neither audition was successful. They had a job offer from Wade Mainer in Raleigh, North Carolina, but did not take it. Instead, Larry and Bob rejoined the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers on January the fourth, 1951. The personnel in that group was the same as before.

On June third, 1951, Larry Richardson quit the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, going to Bristol, Tennessee, where he joined Curley Seckler on WCYB. Bob called Jimmy Martin, then just leaving Monroe’s band, and Jimmy joined the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers. Charlie Cline rejoined the group at this time, as banjoist. Also at this time Bob switched from guitar to mandolin. His first mandolin was an old Gibson model A.

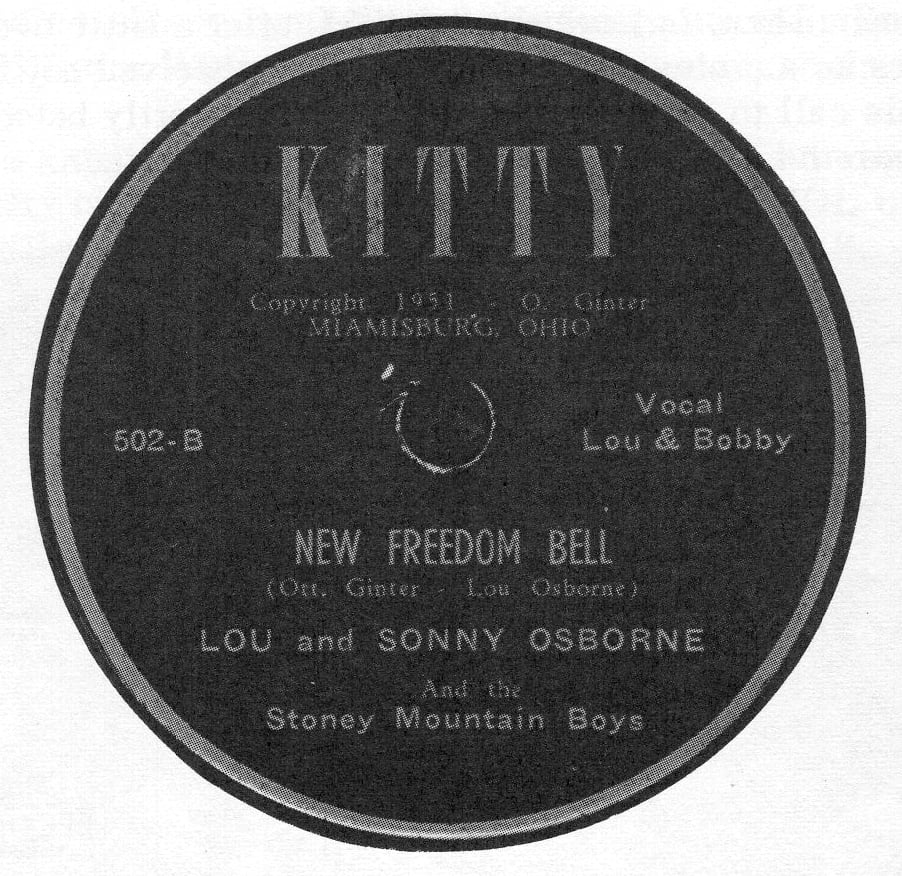

In July of 1951 Bob went home to Dayton and brought Jimmy with him. It is probably at this time that the four recordings for Kitty records were made.1 These rare recordings, which were labeled as “Lou Osborne and the Osborne Family,” consisted of four of Louise’s songs, performed by Bob, Sonny, Jimmy and Louise. The recordings were made at Robert Osborne Sr.’s farm outside of Dayton, on a tape recorder owned by Ott Ginter, the man who had arranged Bob’s first radio audition. These recordings are noteworthy in several ways. They mark the first appearance on record of Bob’s mandolin playing; they also feature Sonny’s first recorded performance—he had been playing the banjo since the end of March, 1951. This was the first recording on which the Osbornes and Jimmy Martin appeared together.

These were the first of Louise’s songs to be recorded. The best known of them is New Freedom Bell, and the Kitty recording of that song is still impressive listening, featuring Bob’s incredibly high tenor to Louise’s lead.

The lyrics of this song describe the replica of the Liberty Bell which was hung in Berlin after the Second World War. Sonny had been playing the five-string banjo only a few months, but even before he made the Kitty recordings with Louise, Bob and Jimmy, he was appearing in public with local musicians Claude Stuart and Jerry Williams. Sonny remembers playing at a furniture store in Franklin, Ohio, and at WPFB in Middletown.

Bob and Jimmy returned to Bluefield in July, taking Sonny with them. They were in Bluefield only a short time for in August Bob and Jimmy quit the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers. Returning to Ohio, they formed a band which they called Jimmy Martin, Bob Osborne and the Sonny Mountain Boys. According to Bob, “Jimmy knew a few people in Nashville and we got us a record contract with King.” On August 27th they recorded four songs at the King Studios in Cincinnati. The band included Curley Ray Cline on fiddle, Charlie Cline on banjo and “Little Robert” (Ralph Guenther) on bass. Following the recording session the group went to Bristol, Tennessee where they worked on WCYB. WSM notwithstanding, WCYB was at this time The bluegrass radio station. Between 1948 and 1951, Flatt and Scruggs, The Stanley Brothers, and many other now well-known bluegrass performers appeared on it.

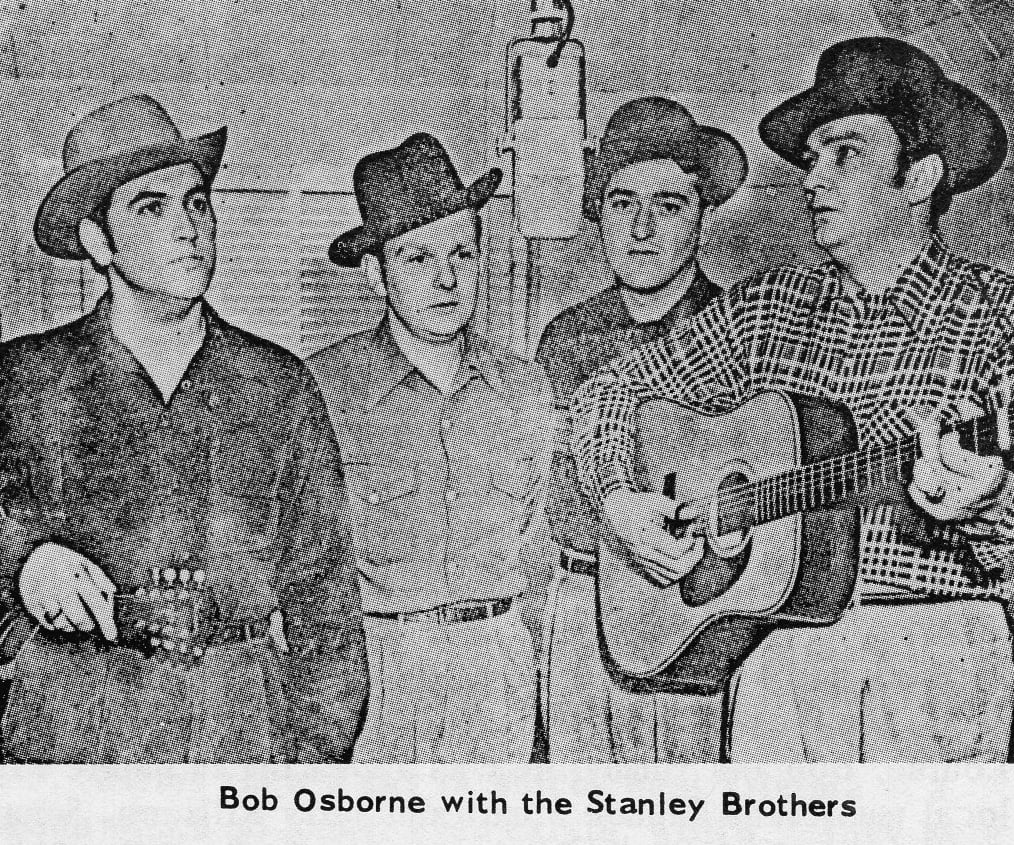

Around the beginning of October, Jimmy Martin left the group and went to Knoxville. The group carried on for several weeks and then, toward the end of October, the Stanley Brothers, just reforming after Carter’s stint with Monroe, hired Bob. 2 Bob worked with the Clinch Mountain Boys for three weeks, along with fiddler Bobby Sumner. Then, in November of 1951, after a little over two years as a professional musician, Bob received notification of his call to service, and, on the 27th, shortly before his twentieth birthday, was inducted into the Marines.

The following summer, Sonny became a member of the Blue Grass Boys. He was 14. “Jimmy helped me get the job with Bill …. We went to Bean Blossom . . . they had the old park back there (in) the back . . . Bill come up there that Sunday with his Blue Grass Boy which was Charlie Cline at the time and so Jimmy worked that day with him and, asked if we could have . . . the job and he said yeah.” 3 They drove to Nashville during the following week. “The first thing I worked with Bill was down on the Opry and we played Raw Hide. Of all things, played Raw Hide!”

This same weekend of July 18-19, 1952, the Blue Grass Boys had a Decca recording session scheduled in Nashville. “It was in the Tulane Hotel, in that old studio up in Tulane Hotel. I’d been working with him two days … I didn’t even know what I recorded.” Among the songs recorded at this time were Footprints In The Snow, In the Pines, The Little Girl and the Dreadful Snake, Memories of Mother and Dad, and Pike County Breakdown. Before recording the latter, Monroe specifically asked Sonny not to play the banjo solo the way Earl Scruggs had recorded it

Unlike Bobby, whose apprenticeship as a professional musician proceeded gradually from small-time amateur jobs to more and more substantial ones, Sonny jumped right in on the professional level, working as a sideman with a star act from the Grand Ole Opry. As a fourteen-year-old, new to the business, he had some unnerving experiences. For example, “One (time) . . . during that first time I worked with (Monroe) why I got my banjo out of the car . . . set it down; the car run over it and busted the neck.” He replaced the broken Gibson RB-100 with an RB-150. At the end of that summer, Sonny left the band and went back to school at home in Dayton.

In October or early November of 1952, Sonny was approached by Check Seitz and Carl Burkhart to record for their Gateway Records. At the time Sonny was playing with Enos Johnson and Carlos Brock at a Labor Temple on Wayne Avenue in Dayton. Enos Johnson had been introduced to Sonny by Jimmy Martin; Carlos was a local boy. “Carlos and I played football against each other.

I was playing for Jefferson township and he was for Centerville.” The band recorded four times at the Gateway studios on Spring Grove Avenue in Cincinnati during the winter 1952-3. They did some performing in the Dayton-Middletown area. Most of the songs they recorded for “Gateway were ‘covers’ of best sellers by Flatt and Scruggs and Monroe. The records were sold through radio mail order offers on stations such as WCKY, Cincinnati, under a number of names. The gospel tunes were sometimes labeled as performed by “The Queen City Sacred Quartet;” the instrumentals as by “Sonny Osborne” and some of the songs as by “Enos Johnson.” They were issued on a number of different labels —Kentucky, Big 4 Hits, Deresco, Ultrasonic and Palace among them. They were still being reissued on drug-store distributed LPs in the mid-60s, under such pseudonyms as “Hank Hill and Stanley Alpine.” These recordings, along with his two summers as a Blue Grass Boy, established Sonny as a well-known bluegrass banjoist. On these recordings he demonstrated that he could, if called upon, come quite close to duplicating Earl Scruggs’ banjo style.

Two of the songs recorded at this time were not “covers”—Sonny’s composition, Sunny Mountain Chimes, a banjo instrumental which achieved great popularity, and Louise’s A Brother in Korea, about Bobby. The latter song makes some interesting comments on the inequities of the draft system at that time.

“I quit the tenth grade about a month before school was out (May, 1953). Matter of fact, I never saw my last report card. I met (Monroe) in Detroit and there was a wild thing happened up there, there was a tornado or something hit Detroit right about that time, or around Detroit. Flint is where it was and we went to work this place and every …. building in this little community we was gonna work, it wasn’t in Flint it was somewhere outside of town. And every building in there was flattened out, laying there on the ground, ‘cept the church steeple. That’s the only thing left standing and that was straight and high.

“Then the next time when I was up there in Detroit I left my banjo in somebody else’s car and so we got there to the date and hell, it was two hundred mile, you know, and so he said, ‘A, boy, what you gon’ do?’ I said ‘Why Bill I don’t know, nothing to do.’ And he said ’You play the mandolin?’ I said, “Why yeah, I can play a little bit of mandolin … I know chords on it.’ And he gave me that old mandolin of his and I went out there, I played that mother, I hung right in there, friends, and took breaks and I was actually having the time of my life.” 4

From the perspective of nearly two decades, Sonny sees his first professional days with the Blue Grass Boys not as an indication of his ability to work with a top level group at an early age but as a sign that the Blue Grass Boys were no longer the exclusive band in bluegrass and had to get musicians. Sonny says, “I’ll tell you, this is the truth, I had no more business being there — I’d been playing seven months or something like that (actually it was slightly over a year) and I had no more business being there than, than a kid working with the band, you know . . . ’Cause I didn’t know my time, I didn’t know any time, I didn’t know any good licks, so it’s evident on those things I cut with him. I didn’t know how to be a trouper and I didn’t carry on and do nothing, you know.” Be that as it may, Sonny learned fast.

The Blue Grass Boys during Sonny’s second summer with the group, in 1953, consisted of Sonny, Jimmy Martin and L. E. White on fiddle. Sonny stayed with the band until August 8, 1953, when Bobby was released from the service. “I didn’t give him a notice of nothing. I just left, I told him, I said ‘I’m goin’ go home tonight’ and that’s it. I went home.”

In August of 1953 the Osborne Brothers did their second recording session together, this one for Gateway, with Enos Johnson on guitar, Billy Thomas on fiddle and Smokey Ward on bass. It was the last session in which they recorded “covers” of other groups’ recordings.

On the seventeenth of November, 1953, they went to Knoxville. Sonny: “. . . we went to Knoxville in November ’53, we worked for Cas Walker, it was me and Bobby and Enos Johnson and L. E. White started. And we called our group the Osborne Brothers and the Sunny Mountain Boys.” Bob: “(Jimmy Martin) was still with Monroe at the time, see.”

This group recorded an EP of six songs for Gateway in February of 1954, while they were working on WROL in Knoxville. Shortly after that recording session, L. E. White (with whom Sonny had played in the Blue Grass Boys) quit to attend barber college. At that time fiddler Ray Crisp and comedian-bassist Kentucky Slim were hired. When Crisp left the group, Joe Stuart was hired as his replacement.

One day during their stay in Knoxville, Charlie Bailey dropped in on them at the WROL studios. He had with him his mandolin, a pre-war Gibson F-5. Bob spent the evening playing the instrument. He liked it and told Bailey to contact him if he ever decided to sell it. Bailey promised to do so and took Robert Osborne Sr.’s phone number.

Around the last week in June, 1954, the band broke up and the Osborne brothers returned to Dayton. According to Sonny, “. . . the reason we left there, (a musician friend) we sent him out on a big booking tour and he went and took up with some woman over in, Sunbright, Tennessee, and stayed over there all week, see, and when he come back, he says, ‘Boys, I just couldn’t find …’—didn’t have no dates, so we starved out, that’s exactly what happened in Knoxville.”

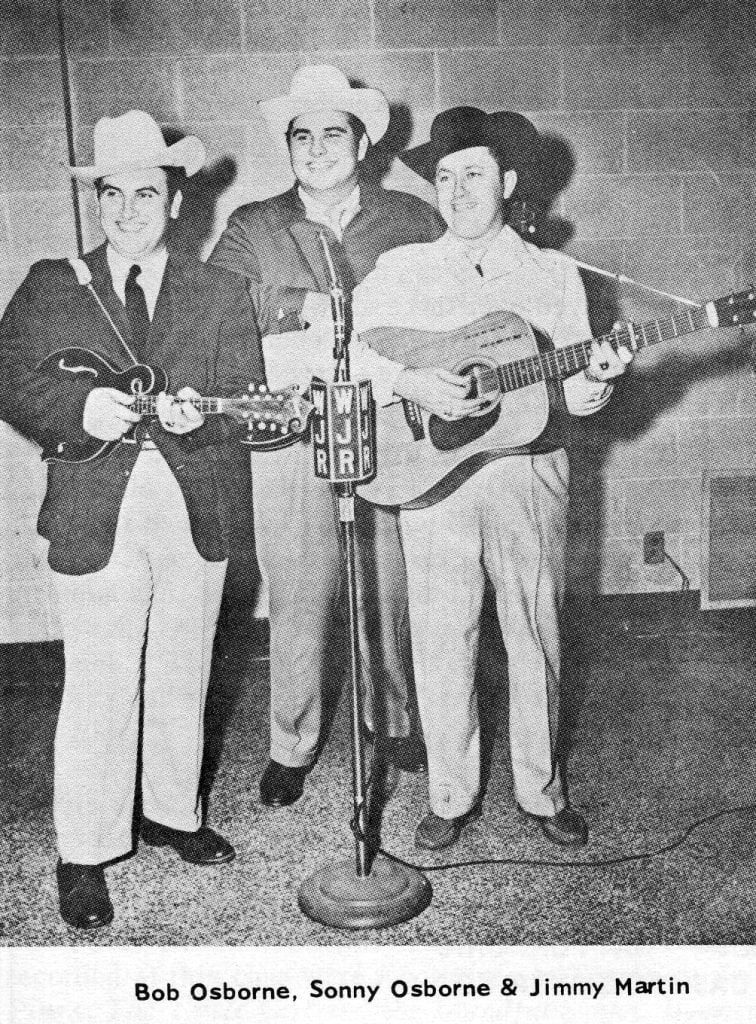

During July, they made an audition tape for WLW in Cincinnati; it was not accepted. At this time Jimmy Martin had recently left the Blue Grass Boys and was playing with Bill Price and J. D. Crowe at the Crown Cafe in Hamilton, Ohio. Bob and Sonny played a few times at the Crown Cafe, and in August of 1954 they decided to form a trio with Jimmy Martin. Their audition with Casey Clark was successful, and, on August 21, they moved to Detroit where they worked for Clark on WJR radio and on CKLW-TV (in Windsor, Ontario).

On November 16, 1954, they made their first recordings as a group in Nashville—six songs with studio musicians “Red” Taylor on fiddle and Cedric Rainwater (Howard Watts) on bass. These recordings are among the classics of early bluegrass, especially 20-20 Vision, which was the best-selling of the six tunes at the time they were released.

One day during the time they were in Detroit, Bob received a phone call from Charlie Bailey, who had decided to sell his F-5. Bob offered him his F-12 and $150.00, and Charlie accepted and told him to send it off. An hour later he called Bob again and said he didn’t want the F-12. Bob offered him $350.00 outright for the F-5 and Bailey agreed to send it C.O.D. Bob didn’t really believe he would do it, but a few days later the post office called to say that there was a C.O.D. package for him. This was before the pre-war F-5 had acquired its present legendary status and Bob asked to see the instrument before paying for it. He hadn’t remembered what it looked or sounded like. Opening the case, he took the mandolin out, hit one chord, and paid over the $350.00. Bob still uses this mandolin.

The Osborne Brothers and Jimmy Martin stayed together as a group in Detroit for a few weeks less than one year. On August 5th, 1955, Bob and Sonny left Detroit and moved to Wheeling, West Virginia, where they began working on WWVA with Charlie Bailey. The name “Sunny Mountain Boys” stayed behind in Detroit with Jimmy Martin, who continued on at WJR with Sam “Porky” Hutchins and Earl Taylor.

Shortly after moving to Wheeling, Sonny acquired his first Gibson Mastertone banjo, a battered old pre-war arch-top which Stringbean helped him find. Working with Charlie Bailey, Bob and Sonny did one recording session at WWVA for a mail-order gospel music package. The same group also did an audition tape for RCA Victor, which included two songs which were eventually recorded by Flatt and Scruggs, Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’ and Not A Drop In The Bucket. Just before Christmas, 1955, Bob and Sonny quit Charlie Bailey’s band at WWVA and returned home to Dayton.

NOTES

- In interviews Bob Osborne dated this recording session as occuring in May, 1951. I have changed it to July for the following reasons: (1) In May, Jimmy Martin was in Nashville working with Bill Monroe, apparently. (2) The notebook which Louise Osborne kept at this time — source for most of the other dates given here—states “In July of 1951 Bob & Jimmy come home—Bob’s family met Jimmy …” Since the Kitty recordings were made at the family home, it seems logical to assume that the family first met Jimmy at the time of the recordings.

- It appears probable that Carter Stanley started working with Monroe at the time that Jimmy Martin left to join the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers (June 3, 1951). At any rate, Carter was with Monroe at a recording session on July 6th, 1951 (see the notes to Decca DL 75066, High Lonesome Sound). Billboard magazine reported on September 1, that Ralph Stanley had been critically injured in an auto accident on August 17th, 1951. If all these dates are correct, then the usual explanation that Carter worked with Bill Monroe while Ralph was recuperating from his auto accident is incorrect, leading one to surmise that the Stanley Brothers had broken up for some other reason in the late spring of 1951. Perhaps some of the readers of BU who have been following the bluegrass scene since way back when can set us straight on what actually happened.

- The present outdoor park at Bean Blossom was built by Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys (Kenny Baker, Roland White, Vic Jordan, and James William Monroe) in May-June, 1968, for the second annual bluegrass festival. There had been an outdoor stage on the same site during the late forties and early fifties, but it fell into disuse and was more or less abandoned when the park was closed for the season following the burning of the Jamboree barn in the spring of 1958.

- This incident occured during the part of the show prior to Bill Monroe’s introduction to the audience, when the Blue Grass Boys would appear without Monroe, under the name of the Shenandoah Valley Trio.

Neil V. Rosenberg

Memorial University of Newfoundland

Click here to read Part 2: https://www.bluegrassunlimited.com/article/the-osborne-brothers-part-two-getting-it-off/